Jeff Vail - Litigation Strategy & Innovation

The following are the titles of recent articles syndicated from Jeff Vail - Litigation Strategy & Innovation

Add this feed to your friends list for news aggregation, or view this feed's syndication information.

LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose.

| Friday, February 7th, 2014 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 am | Colorado Litigation Report Take a look at the Colorado Litigation Report, a site with very useful, short summaries of Colorado appellate opinions (best of all, published on a very regular basis, unlike this blog of late... but soon to change). |

| Tuesday, September 17th, 2013 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 2:20 pm | The Nature of the (Law) Firm John Robb has a thought provoking comment on Ronald Coase's classic paper The Nature of the Firm. Robb points out: Robb thinks this no longer necessarily holds true today, thanks to largely online, open-source markets that can dramatically increase the efficiency of building what I've been calling "ad hoc firms." This trend and potential also applies to law firms. Traditionally--and lawyers generally not known for their innovation in terms of their own business structures--law firms are classical "firms" precisely for the reasons highlighted by Coase: there is substantial cost involved in assembling the right team to optimally serve a client. That inefficiency, however, is melting away for those prepared to capitalize on the potential of new marketplace formats for labor and services. Just as Coase pointed out, if there were no costs involved in assembling the right team, then all legal services would be delivered by tailored and just-in-time assemblages, or "ad hoc firms." In fact, if there were no costs involved in creating such assemblages, it's quite clear that ad hoc firms could deliver superior knowledge, talent, service and value than traditional firm models. I'm not sure whether we've already crossed the threshold where the value derived outweighs the cost of the ad hoc firm model, the obvious desire of traditional firms to keep their heads firmly planted in the sand notwithstanding. What I am confident in is that we're rapidly moving in that direction, and that both legal service providers and consumers need to position themselves for the day when that line is undeniably crossed. And, because of the widespread reticence to even acknowledge this dynamic let alone do something about it, there is tremendous potential for those individuals positioning themselves for that future today. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 2:20 pm | Motions to Dismiss This post is part of my Colorado litigation checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. It is an overview of filing motions to dismiss in Colorado and Federal courts--where the governing rules and procedures are similar, these checklists will focus on motions in Colorado state court and will not significant differences for filings in Federal court. As each of the following checklists are completed, I will link to them from the text below. - C.R.C.P. 12(b) provides the legal basis for motions to dismiss. A motion to dismiss may be filed for several reasons, and against several types of claims--each with their own checklist below. - Motion to Dismiss Checklists - Rule 12(b)(1) - Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Subject Matter Jurisdiction - Rule 12(b)(2) - Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Personal Jurisdiction - Rule 12(b)(3) & (4) - Motion to Dismiss due to Insufficiency of Process or Insufficiency of Service - Rule 12(b)(5) - Motion to Dismiss for Failure to State a Claim Upon Which Relief Can Be Granted - Rule 12(b)(6) - Motion to Dismiss for Failure to Join a Party Under Rule 19 - Special Considerations: Motion to Dismiss Counterclaim or Crossclaim - Other Related Motions: - Rule 12(e) Motion for More Definite Statement - Rule 12(f) Motion to Strike - Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings Best Practices - In Colorado, if a motion to dismiss is granted that dismisses the entirety of an action brought by one party containing claims in tort, then an award of attorneys' fees is mandatory pursuant to C.R.S. § 13-17-201. An award of attorneys fees is mandatory whenever all claims by one part against another are dismissed, even if other claims remain unresolved. See Stauffer v. Stegemann, 165 P.3d 719 (Colo. App. 2006). - Always consider the value of dismissing certain claims--for example, even if a complaint's lone tort claim is vulnerable to a motion to dismiss, is it more valuable to keep the claim alive for purposes of insurance coverage issues? - In responding to a Motion to Dismiss, consider whether it is wiser to voluntarily dismiss the claims without prejudice to avoid a mandatory award of attorneys fees, fix the deficiencies in the complaint highlighted by the motion to dismiss, and refile. Always consider statute of limitation issues and other potential bars to re-filing. - While most courts will write their own order addressing a motion to dismiss, it is still wise to file a simple and direct proposed order with the motion (or response in opposition). - Jeff Vail is a business litigation attorney in Denver, Colorado. Visit www.vail-law.com for more information. This post is part of my Colorado litigation checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 2:20 pm | The Future of the Legal Industry? Jordan Furlong has an excellent take of the future of the legal industry in his latest post, The Law Firm of the Future: Thompson Reuters. I think his analysis will prove prescient for large and mid-size law firms over the coming decade. Big firms that aren't on top of this trend (or small firms that try to emulate their business model) are in the process of pricing themselves out of the market. More importantly, though, firms of ALL sizes simply can't ignore concepts like open-source development, flat networks, geoarbitrage, and process automation any longer. In my mind, one of the most interesting and promising areas for change in the legal profession (and economy in general) will be the rise of ad hoc, networked providers of legal services--I won't call them "firms" because they meet neither the legal ethics nor classical economic of such. In fact (perhaps this shows where my mind is, as I'm about to file a complaint along these lines), the most analogous legal structure is probably the RICO "enterprise-in-fact"--but I digress. I've long found this area of thought fascinating. Many people who know about the full range of my personal interests have often wondered how my interest in organizational theory, self-sufficiency, networked economies, consciousness/emergence theory, etc. will come together into my legal practice. Here's my answer (which may also provide more insight into why I chose to start a solo litigation practice): we have reached a bifurcation point in the legal profession, with one path diverging to large corporate structures--much like in modern accounting--that will "optimize" the human element (i.e. pay as little as possible for as much work as possible where labor is cheapest), and the other path diverging to well-connected individuals who can leverage personal attention, innovation, and access to the large legal/LPO/professional services corporations of the other path to deliver exceptional service to clients. This second path is where I think humans (as opposed to stock markets) will find personal and professional fulfillment. This second path is also far more adaptable to the rapidly changing and multifaceted end needs of the legal consumer. This, I believe, will define the structure of the legal industry in the coming few decades: agile, networked professionals--individuals capable of assembling into ad hoc firms, rather than firms composed of individuals--will leverage access to more rigid and powerful LPO structures to provide millions of tailored legal solutions to clients. Contrast this with present-day "firms" that will gradually fade, some begin absorbed into the large, corporate LPO-structures (with commensurate decline in the fulfillment of their component individual attorneys), and others that will voluntarily dissolve into networks nimble enough to prosper. What path will your firm/career take? Or, if you're a client of legal services (and everyone is, they just often don't realize how important their consumption of legal services in one form or another is to their lives), how much longer will you put up with the bloated, inefficient, and overpriced services offered by traditional firm structures? |

| Saturday, July 20th, 2013 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 1:32 am | The Oil Drum Sadly, one of my favorite websites (and a website where I was previously a contributing author), www.theoildrum.com, is shutting down (actually converting to an archive, there will just be no new content). There are a variety of reasons for this, but in my opinion it doesn't reflect that energy has become any less central to questions about our civilization or its future. A few articles I wrote for TOD in the past that are still worth considering (perhaps more so now than ever): Oil Demand Destruction & Brittle Systems Geopolitical Feedback Loops in Peak Oil The Renewables Gap Predator-Prey Dynamics in Demand Destruction and Oil Prices Some weekend reading... |

| Friday, December 28th, 2012 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 1:48 am | Preserving ESI on Twitter Once litigation is “reasonably anticipated,” parties have an obligation to preserve all potentially relevant material. That obligation extends to information reasonably under a party’s control, even if it is not actually in its possession. This raises significant concerns when it comes to information on social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter—the information may well be relevant, should likely be preserved, but is it in the reasonable control of the party? Some recent changes with Twitter reveal that the answer is yes—it is reasonably under the control of the party, and must be preserved. Fortunately, Twitter also now provides an easy-to-use tool to preserve this information. During one of Twitter’s quarterly “Hack Weeks”, employees engineered Twitter archiving, which allows users to access Tweets from their Twitter account past. On December 19, Twitter launched this new feature to a small group of users who have their account language setting on English. It’s not yet clear whether this archiving feature will include “Direct Messages,” so attorneys should ensure that any such information is either captured or separately preserved. It will be rolling out to all other users over the coming weeks and months, according to Mollie Vandor, part of Twitter’s User Services Engineering Team. Archiving allows users to access and download Tweets from the beginning of their account, including retweets. After they have their account set up to access the archives, they can view Tweets by month, or search their archive based on certain words, phrases, hashtags, or @usernames, according to Vandor’s blog. You might be wondering how you can access the archiving feature on your Twitter account. After logging into your account, go to Settings, scroll down to the bottom, then check for the feature, which will allow you to access your Twitter archive. Click on the button, and you will receive email instructions on how to access your archive once it is ready to download. Some thoughts and potential best practices for attorneys: - - Include Twitter usage in initial interviews with clients regarding ESI - - Ensure clients are directed not to delete or modify their Twitter accounts in a litigation hold letter until such time as the account can be fully preserved - - It’s not yet clear whether the archiving feature will include Direct Messages or lists of accounts followed by a specific user, so extra care should be taken to ensure this information is separately preserved if applicable |

| Saturday, December 22nd, 2012 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

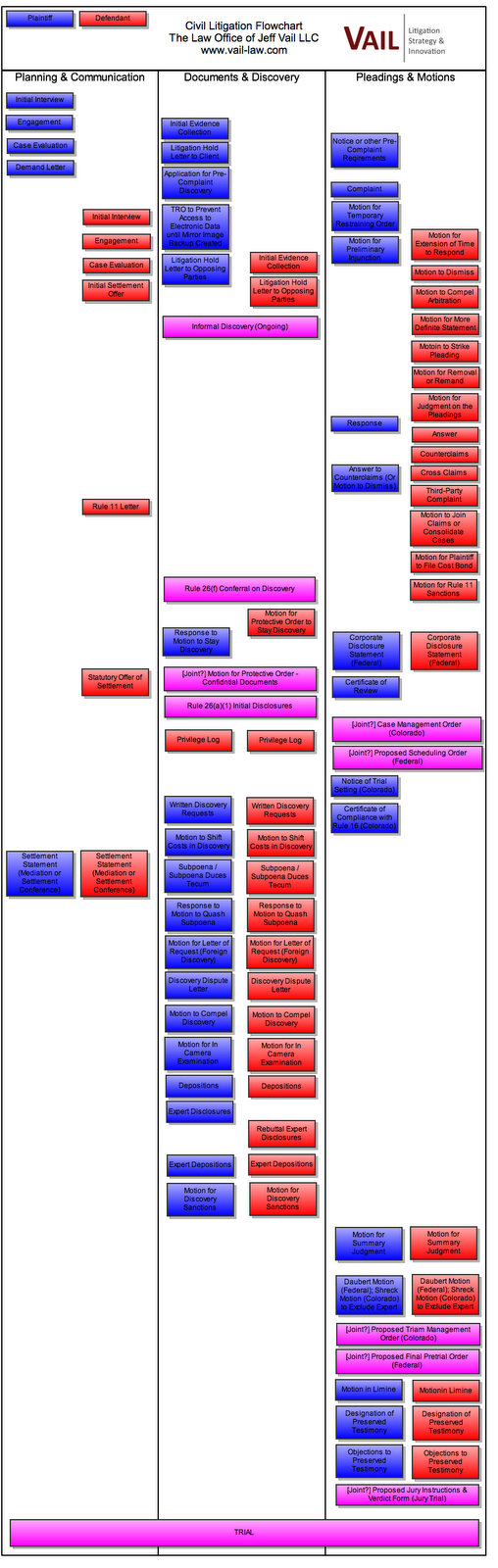

| 12:17 am | Litigation Flowchart I'm working on assembling a flowchart for civil business litigation in Colorado state and federal courts, which will eventually link to associated checklists. This is not a definitive outline of the litigation process in all cases, but is general legal information that may be helpful in general litigation planning. Here's the first draft: Jeff Vail is a business litigation attorney in Denver, Colorado. Visit www.vail-law.com for more information. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 12:17 am | Learning Law: Solo v. Associate v. Contract Lawyer At the end of the day, every lawyer (and every person, for that matter), is a "solo"--a brand of one, a serial entrepreneur, etc. Whether we see ourselves expressly in these terms (as I and other true solo practitioners are forced to), or whether we shroud ourselves in the gloss of "employee," "associate," or "partner" is ultimately irrelevant. In the global marketplace where "employees" are but one more cog in the system to be optimized, the disparity between this reality and the common desire to hide one's head in the sand of a large and established employer is especially striking. In my opinion, nearly everyone would be well served to view themselves as the duality of one-person venture/consciously assembled network (21st century thinking) rather than the outdated employee/employer (or, for that matter, citizen/Nation-State, but that's the story for another essay). Of course, when it comes to law, or any other profession that deals with such complexity, the reality of "venture of one" runs into the need for training, skill building, mentorship, etc. Richard Susskind has argued that this is one of the remaining sources of legitimacy for traditional, large law firms--they act as a sort of "teaching hospital," taking young attorneys under their wing and gradually training them in the art and science of the law. Another traditional approach is for junior attorneys to start off working as a public defender or district attorney, and then after they have a fair amount of trial experience under their belt they re-start in civil litigation (never mind the enormous substantive and procedural differences between the two fields--akin to the transition between surgery and psychiatry, or vice versa). At the opposite end of the spectrum, there's always the option of being a "venture of one" in the form of a contract lawyer for large firms. In most (though, admittedly, not all) cases, this is a dead end street-- document review or repetitive drafting that employs licensed attorneys normally for no reason other than to be able to check the box of some practice of law or insurance requirement. This route tends to be devoid of mentorship or real learning, and the experience gained is rarely of much real value. (Of course, there are other arrangements, often also labeled "contract attorney," that involve much more substantive research, drafting, or advocacy, which are true independent contractor relationships rather than "temporary hire" type positions--labels can be dangerous). Fortunately, I think there is great potential for junior attorneys to structure themselves expressly as solo practitioners, yet still reap the advantages of training, mentorship and experience to be gained in a traditional large firm setting. It's something I've written about frequently over the past few months: the Ad Hoc Firm. In a nutshell, every case should be a temporary assemblage of legal talent tailored specifically for the job at hand, and flexible to grow and contract as the legal task itself evolves. In the litigation realm, that might include the Rainmaker (the person who brings in the client), the Coach (who assembles and manages the team--often called the quarterback transactional matters, though I think "coach" is the more fitting sports analogy), the Strategist (who lays out the grand plan), the Expert (the person or people with subject matter expertise required), and then various Lieutenants (who take charge of individual tasks, from the minor research project to larger issues like discovery or trial). Of course, in all but the largest of matters one person will fill several, often all of these roles simultaneously. However, I think it's still important to view them as separate functions--regardless of whether it's just one attorney or a team of dozens spanning several continents. How does all of this relate to the training of junior lawyers? Within the ad hoc firm, everyone is their own enterprise, and they have come together voluntarily to form a team to address a legal challenge. For the junior lawyer, that can mean offering one's services as a "Lieutenant" in a discovery matter, in dealing with a specific substantive area of the law, sitting second chair at trial, etc. The junior lawyer can also be the Coach or Rainmaker--what better way to pitch a client than to explain your intent to assemble a team of highly experienced attorneys, with a reasonably priced and highly motivated junior attorney taking up the often time-consuming task of coordination? And, unlike in a large, monolithic law firm, the junior lawyer has flexibility in balancing income, education and experience. I know many junior attorneys at large law firms that would love to be the second attorney in a civil trial, yet calcified firm business models often don't permit this as it would be impossible to bill for the attorney's time. It's a Catch-22: often you can't get the experience until you're experienced enough to justify billing for the work. A junior solo attorney, on the other hand, has the opportunity to make a very attractive pitch: essentially "let me try this case with you, and cross examine three witnesses, and I'll work for 1/3 my normal rate." This isn't particularly revolutionary. It's common advice for junior attorneys to be told to try to get some pro bono work to build experience, or to try to attract small clients of their own and gradually build to more sophisticated matters. But this rarely does away with the Catch-22 caused by existing models of experience and billing. Interestingly, law students seem to have no problem forking over $40k a year to be lectured on the law by professors, but few licensed attorneys seem to be willing to forgo even a fraction of that income for the chance to gain truly valuable experience. This is where I think a paradigm shift is in order: the more junior attorneys conceptualize themselves as one-person enterprises, regardless of whether someone else sees them as an employee, the more they will be in a position to demand (or create for themselves) the kind of experience they need and desire. As a bit of an afterthought, it's also worth noting that clients will be increasingly unwilling to subsidize the highly inefficient training models of large law firms--especially the kind of sophisticated clients with sophisticated matters that attorneys hope to work on. The very Catch-22 that prevents junior associates from getting the kind of experience they need (because clients don't want to pay inflated large firm billing rates for the associate to learn on the job) forces clients to pay for the high rates of more seasoned attorneys. An ad hoc firm, however, that provides an appropriate mix of high-paid and seasoned attorneys with much lower paid apprentices will enjoy a significant competitive advantage when pitching work. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 12:17 am | Mentorship, Leadership, Validation and the Ad Hoc Firm The vision of the ad hoc law firm can be compelling: agile assemblages of just the right talent, just in time, to efficiently meet a clients needs. In this running commentary on the prospects for the ad hoc law firm (or any industry, really), I'd like to touch briefly on three topics: 1. Mentorship: As Richard Susskind points out, one of the roles for the "large" law firm is essentially that of a teaching hospital--a place where junior lawyers with only academic experience are put through the paces and given real world training. How does the need for this kind of training meet with the needs of the ad hoc firm? It seems to me that it's a huge opportunity: to the extent more seasoned lawyers are willing and skilled at mentorship, they can offer this as part (or all) of the compensation of junior lawyers on their teams--and also offer the prospect of developing relationships that will lead to employment in future ad hoc assemblages. Especially in today's job market, law students are scrambling for choice unpaid internships, and increasingly licensed attorneys are doing the same. Even senior attorneys might jump for the training opportunity of a high profile case (i.e. appeal to the US Supreme Court). While at first the need for training, development and advancement may seem like a challenge to the ad hoc firm model, I think it should instead be seen as an opportunity--albeit not one that is currently embraced by the law school placement office or "accepted" career path expectations of most graduates. 2. Leadership/Project Management: Similarly, project management and leadership is a key part of ad hoc law firm operations. Of course, this is very true of litigation or deals in monolithic firms as well, though it's often not recognized as such and very rarely trained or adequately staffed. In the transactional world it's quite common to hear of "quarterbacking the deal," and litigation management is increasingly an appreciated talent, but these are usually afterthoughts when it comes to attorney training (both in law school and in professional development). Should project management be outsourced to PM specialists? Or attorneys with additional specialized training? Where is the "break even" point when considering how much attention to pay to project management on small cases, or whether to have a PM specialist? What about classical leadership training--something I've always valued most about my experience as a military officer where I was in charge of nearly 30 people at age 22. Lawyers rarely have much experience as leaders, let alone any formal training in leadership, yet it is clearly an important skill in even moderately complex litigation, and will become even more important as the potential of the ad hoc law firm process is increasingly realized. 3. Validation/Metrics: Jonathan Soroko's insightful comment in my last entry highlights the importance of knowing what you're getting when putting together ad hoc talent. In many cases we can do this based on past experience working with people--but that ignores the initial hurdle in setting up such an ad hoc system, as well as the ongoing inefficiency of evaluating potential new talent. What kind of validation system or metric for performance, potential, and value should be used when assembling a team? Some initial thoughts are the Ebay buyer/seller rating system, or some kind of review-based metric (one example, though certainly imperfect, is the AVVO lawyer rating system). John Robb has also been posting very interesting thoughts on "meta currencies"--social networking valuation algorithms that can compute the value of input to the social network from all contributors--another potential. While I'd prefer such systems to be transparent, I can also envision the potential market for proprietary rating systems--possibly even that facilitate the assemblage of an ad hoc firm, and/or stand behind the performance of their members based on their ratings... |

| Wednesday, December 12th, 2012 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 10:17 pm | Corporate Disclosure Statement per F.R.C.P. 7.1 This post on drafting the Corporate Disclosure Statement required by F.R.C.P. 7.1 is part of my Federal Litigation Checklist. - Checklist: - F.R.C.P. 7.1 requires the filing of a disclosure statement by all nongovernmental corporate parties - The filing requirement is simple: -- Identify any parent corporation -- Identify any publicly held corporation owning 10% or more of the party's stock -- Or, if no such parent or corporation holding 10% or more exists, say so - The disclosure statement must be filed at the time of the first appearance or filing by the party, and must be updated "promptly" if any of the disclosed information changes - Thoughts & Best Practices: - While the corporate disclosure statement may seem like a trivial administrative filing, it can have important ramifications. For example, the failure to file a corporate disclosure statement may permit a parent company that should have been disclosed to be added after the deadline for adding parties. - Sample Corporate Disclosure Statement - Jeff Vail is a business litigation attorney in Denver, Colorado. Visit www.vail-law.com for more information. - This post on filing a Corporate Disclosure Statement as required by F.R.C.P. 7.1 is part of my Federal Litigation Checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 10:17 pm | Federal Litigation Checklist This post is part of my Colorado litigation checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. It is an overview of procedural issues and motions in Federal Court civil lawsuits. Where possible, the following procedures and checklists apply rules and case law applicable in the United States District Court for the District of Colorado. As each of the following checklists are completed, I will link to them from the text below. - - Complaint, Summons & Cover Sheet -- Pleading Jurisdiction -- Pleading Venue -- Twombly Standard - Corporate Disclosure Statement - Entry of Appearance - Answer - Motion to Intervene - Motions to Dismiss - Motion to Compel Arbitration - Motion for Rule 11 Sanctions - Motion for Protective Order to Stay Discovery - Motion for Protective Order (General) - Case Management Order - Discovery Requests - Jeff Vail is a business litigation attorney in Denver, Colorado. Visit www.vail-law.com for more information. This post is part of my Colorado litigation checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 10:17 pm | Domestication of Foreign Judgments in Colorado This Checklist on the domestication of foreign judgments is part of my Colorado Litigation Checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. When you have obtained a judgment from outside of Colorado against a Colorado resident, you must domesticate the judgment in Colorado before you can proceed to execute on the judgment (attempt to collect). Fortunately, in Colorado the domestication process is relatively simple: - Checklist: - In Colorado, the domestication of foreign judgments is governed by the Uniform Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act, C.R.S. Section 13-53-101 et seq. - The court filing fee is $166 per judgment to be domesticated (note: a single judgment against multiple judgment debtors, jointly and severally, counts as only one judgment) - Draft a pleading styled Notice of Filing of Foreign Judgment - Include as an attachment an authenticated copy of the foreign judgment - Include as an attachment an affidavit including (1) the name and last-known postal address of the judgment debtor(s); (2) the current postal address of the judgment creditor; and (3) the name and current address of the judgment creditor's Colorado attorney - The clerk of the court should send notice of this filing to each of the judgment debtors listed, however this notice requirement can also be met by filing proof of mailing, by certified mail, notice of the filing and the judgment to judgment debtors - 10 days after the filing of the judgment (not receipt of the notice by the judgment debtors), efforts to collect or execute on the judgment in Colorado courts may commence - Jeff Vail is a business litigation attorney in Denver, Colorado. Visit www.vail-law.com for more information. - This checklist is part of my Colorado Litigation Checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 10:17 pm | Complaint This Complaint Checklist is part of my Colorado Litigation Checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. A Complaint is used to initiate a lawsuit. Before filing, an attorney should consider at a minimum the following: - Checklist: - Pre-Complaint Investigation - Review potential claims and their elements - Ensure there is factual support, or a good faith belief that you will obtain factual support, for each element of each claim - Ensure that a federal court Complaint meets the standard set forth in Twombly - Even if the complaint will be filed in state court, there are reasons to still ensure it meets the Twombly pleading requirements - Special considerations for complaints against multiple defendants - Jeff Vail is a business litigation attorney in Denver, Colorado. Visit www.vail-law.com for more information. - This Complaint Checklist is part of my Colorado Litigation Checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. |

| Saturday, December 1st, 2012 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:48 pm | E-Discovery White Paper Our new E-Discovery white paper is available now: E-Discovery White Paper Entitled "Avoiding E-Discovery Nightmares: Simple Steps for Small Businesses," this paper discusses key steps small businesses should consider to prepare for the eventuality of electronic discovery in litigation. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:48 pm | Colorado State E-Discovery Law In 2009, the Colorado Supreme Court rules committee rejected incorporating either the Federal or proposed Uniform E-Discovery Rules into the Colorado Rules. See http://www.courts.state.co.us/userfiles/f Normally, the similarity between Colorado and Federal rules of civil procedure allow case law interpreting federal rules to be cited as persuasive authority in Colorado state court cases. See, e.g., Benton v. Adams, 56 P.3d 81, 86 (Colo. 2002) ("When a Colorado rule is similar to a Federal Rule, [the court] may look to federal authority for guidance in construing the Colorado Rule"). The Supreme Court Rules Committee's decision, however, distances Colorado state court discovery jurisprudence from case law interpreting the federal rules regarding e-discovery, and makes a review and analysis of Colorado state court case law on e-discovery issues all the more relevant. Assuming, for the moment, that Colorado courts will not be easily persuaded by citations to federal e-discovery case law following this Rules Committee decision, what is the current state of Colorado state court e-discovery law? Unfortunately, the answer is “very limited.” For example, only three Colorado state court cases contains the phrase “Electronically Stored Information,” and none contain the phrase “e-discovery” or "ediscovery." See Wiggins v. Wiggins, 279 P.3d 1 (Colo. 2012) (quoting C.R.C.P. 45 as permitting subpoenas to request ESI); People v. Buckner, 228 P.3d 245 (Colo. App. 2009) (interpreting C.R.E. 801); Tax Data Corp. v. Hutt, 826 P.2d 353 (Colo. App. 1991) (public records access includes access to ESI). Further, these cases provide no real guidance to e-discovery rules or limits in Colorado. There are, however, a few cases that provide useful guidance to E-Discovery practice in Colorado state courts: One case contains the phrase “Native Format” – People v. Preston, 276 P.3d 78, 85 (Colo. 2011). That case states that “[w]hether or not Respondent believed he was adhering to normal procedures, his conduct had the effect of ‘promot[ing] principles of gamesmanship’ and ‘hid[ing] the ball,’ and his lack of diligence in responding to Rice’s requests was tantamount to obstructing the discovery process. Likewise, that discoverable information relevant to Hoch’s claims was stored electronically, be it in ‘native format,’ Windows, or scanned PDF files, cannot justify departure from Respondent’s obligations as an attorney; Respondent had a duty to disclose and produce “any data compilations from which information can be obtained [and] transferred, if necessary, . . . through detection devices into reasonably useable form.” Another case provides some guidance in requesting inspection of a computer by computer forensics experts. In Cantrell v. Cameron, 195 P.3d 659 (Colo. 2008), the Colorado Supreme Court considered a challenge to the trial court’s order compelling production of Defendant’s laptop for inspection. The Supreme Court vacated the order and remanded for a hearing to assess the scope of inspection required to determine first if the laptop was in use during the accident. Here, the substantive information on the laptop was not relevant to the claims. Rather the relevant question was whether the laptop was in use by the driver at the time of the car accident. The Court, concerned about the invasion of Defendant’s privacy, held that the three-part test from Martinelli v. District Court, 612 P.2d 1083, 1091 (Colo. 1980), was the appropriate test in these circumstances, and that the trial court failed to apply this test. The Court reasoned that there may be less-intrusive options available to determine whether the laptop was in use at the time of the accident, relying on alternative recommendations of a computer forensics expert, the order compelling production was vacated and the issue remanded for the trial court to balance these issues properly under Martinelli. Generally, however, Cantrell supports the notion that a party may request inspection of a computer by its computer forensics expert. In Lauren Corp. v. Century Geophysical Corp., 953 P.2d 200 (Colo. App. 1998), the court affirmed an order imposing sanctions and granting adverse inference instructions at trial due to failure to produce computers for inspection and subsequent spoliation when the party then disposed of the computers in question. While the case is short on broadly applicable tests or principles to govern e-discovery disputes, it does approve spoliation sanctions where computer hardware—here only relevant because it contained ESI—was not produced and later destroyed despite requests in discovery to inspect these computers. Colorado courts' guidance on the discoverability of social media is similarly sparse: no case mentions the phrase “Twitter,” and only one uses the phrase “Facebook,” though not in an e-discovery context. See People ex rel. R.D., 259 P.3d 562 (Colo. App. 2011). The situation with respect to discovery of text messages is no better, with several cases discussing text messages in a criminal context, but no discussion in the context of the acceptable scope or procedure for their discovery. Perhaps most importantly, the text of C.R.C.P. 34 and C.R.E. 1001 leave the door wide open to requesting production of ESI if carefully and creatively applied: For example, C.R.C.P. 34(a)(1) allows for production and inspection of “data compilations from which information can be obtained.” As suggested in Preston, above, this likely includes electronically stored, native format files because these are ultimately nothing more than “data compilations from which information can be obtained.” This phrase should permit requests for production of native format files, email and attachments in native file format (e.g. .PST files), as well as the production and inspection of file structures, databases, electronic accounting files, etc. C.R.C.P. 34(a)(1) also covers documents that are under a party’s control, though not in its actual possession, and which are obtainable upon its order or direction. See Michael v. John Hancock Mut. Life Ins. Co., 334 P.2d 1090 (1959). This provision should extend the reach of Rule 34 to cover cloud-based and hosted “data compilations” such as Google docs, email hosted by third-party providers, information in Facebook and Twitter accounts, cloud-based storage systems such as Dropbox, cloud-based project management systems like Basecamp, etc. In certain situations, these sources may yield a treasure trove of relevant information. C.R.C.P. 34(a)(1) also allows for the requesting party to “inspect and copy, test, or sample any tangible things which constitute or contain matters within the scope of C.R.C.P. 26(b).” This should permit actual inspection and copying of computers, hard drives, or specific folders within computers and hard drives if copying the entire device would be overly broad or unduly burdensome. Additionally, this should permit extracting data from cell phones (text messages, call records, voicemails, photos). Many attorneys consider E-mail to be especially valuable in discovery because it often provides candid communications between parties. This characteristic is equally, or even more true of text messages, Tweets, or Facebook posts, especially among a younger generation where it may be common to send dozens of such messages in a day with little thought as to editing, consequences, or discoverability. Finally, Colorado's Civil Access Pilot Project implemented in business cases in some Colorado districts provides additional rules that impact e-discovery, including Rules 1.3 (proportionality in discovery of ESI), 6.1 (preservation of ESI), 6.2 (cost of preservation borne by producing party), and Appendix B (Case Management Order format requires parties to discuss their strategy re: ESI). However, as the rules have been in effect less than a year, no appellate orders currently exist discussing the scope or providing guidance in interpreting these ESI-related rules. Arguably these rules are mere formalization of good case management practices already in effect, and may support arguments outside the CAPP system about the proper manner for management of e-discovery. The Law Office of Jeff Vail focuses on providing innovative and cost-effective business litigation solutions to Colorado small and medium-sized businesses. If you have a business dispute, or if you need advice or guidance in E-Discovery matters in Colorado courts, visit our website to learn more about our services. |

| Wednesday, October 24th, 2012 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 12:50 am | Affirmative Defenses (Litigation Checklist) This post is part of my Colorado litigation checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. It is intended to assist in identifying appropriate affirmative or additional defenses for inclusion in an answer. To my knowledge, this is the most complete list of affirmative defenses available, currently consisting of 149 separate affirmative defenses. This list is updated continuously, but certainly isn't complete--if you have a suggested addition, please contact me or comment below. -- C.R.C.P. 8(c) requires a party to "set forth affirmatively . . . [any] matter constituting an avoidance or affirmative defense." - Checklist & Best Practices to Consider: - Consider each of the below affirmative defenses--does it potentially apply in your case? Rule 8(c) requires that both defenses to liability and defenses that potentially mitigate damages must be set forth in the pleadings. Indus. Comm'n v. Ewing, 418 P.2d 296 (Colo. 1966). - If a defense is not raised by the pleadings, it may still be tried by the express or implied consent of the parties. See C.R.C.P. 15(b); Great Am. Ins. Co. v. Ferndale Dev. Co., 523 P.2d 979 (Colo. 1974). However, it is error for a trial court to consider a defense first presented at trial if it is objected to. Maxey v. Jefferson County Sch. Dist. No. R-1, 408 P.2d 970 (Colo. 1965). Accordingly, while pleadings may be amended to add additional affirmative defenses, it is essential that all defenses to be raised at trial are pleaded before trial, and that any attempt to raise defenses not pleaded is objected to. - Note that, unlike affirmative defenses where the defendant bears the burden of proving the defense, some of the following are more properly styled "additional defenses" where the plaintiff bears the burden of proving that the defense does not apply (e.g. service of process). - While the vast majority of these defenses will not apply in any given case, review of the complete list may be an especially helpful tool in brainstorming at the outset of a case. ***DO NOT PLEAD A LAUNDRY LIST. As stated above, the vast majority of these affirmative defenses will not apply to any given case--they are intended as a brainstorming tool, and certainly should not be included in full. Rule 11 requires that you have a good faith basis for believing an affirmative defense actually applies before pleading it, and in discovery you will likely need to respond to an interrogatory identifying all factual bases for every affirmative defense you plead. - List of Affirmative Defenses (Partial): - failure to state a claim upon which relief may be granted (almost always use) - statutory defenses prerequisites (these will vary depending on the claims) - preemption by federal or other law - accord and satisfaction - arbitration and award - assumption of risk - economic loss rule - contributory or comparative negligence - intervening cause - supervening cause - claimants own conduct, or by the conduct of its agents, representatives, and consultants - discharge in bankruptcy - duress - estoppel - recoupment - cardinal change - set off - failure of consideration - fraud (generally, as an equitable defense, as opposed to fraud in the inducement, below) - fraud in the inducement - illegality - injury by fellow servant - borrowed servant - laches - license - payment - release - res judicata - statute of frauds - statute of limitations - waiver - unclean hands - no adequate remedy at law - failure to mitigate damages (or, in some circumstances, successful mitigation of damages) - rejection of goods - revocation of acceptance of goods - conditions precedent - discharge - failing to plead fraud with particularity - no reliance - attorneys’ fees award not permissible - punitive damages not permissible - lack of standing - sole negligence of co-defendant - offset - collateral source rule (common law) or as codified in statute (see, e.g., C.R.S. Section 13-21-111.6) - improper service - failure to serve - indemnity - lack of consent - mistake - undue influence - unconscionability - adhesion - contrary to public policy - restraint of trade - novation - ratification - alteration of product - misuse of product - charitable immunity - misnomer of parties - failure to exhaust administrative remedies - frustration of purpose - impossibility - preemption - prior pending action - improper venue - failure to join an indispensable party - no private right of action - justification - necessity - execution of public duty - breach by plaintiff - failure of condition precedent - anticipatory repudiation - improper notice of breach - breach of express warranty - breach of implied warranty - parol evidence rule - unjust enrichment - prevention of performance - lack of privity - merger doctrine - learned intermediary or sophisticated user doctrine - adequate warning - no evidence that modified warning would have been followed or would have prevented injury - manufacturing/labeling/marketing in conformity with the state of the art at the time - release - res judicata - assumption of the risk - product was unavoidably unsafe - product provides net benefits for a class of patients - spoliation - damages were the result of unrelated, pre-existing, or subsequent conditions unrelated to defendant's conduct - lack of causal relationship - act of god (or peril of the sea in admiralty cases) - force majeure - usury - failure to act in a commercially reasonable manner - acquiescence - doctrine of primary or exclusive jurisdiction - exemption - failure to preserve confidentiality (in a privacy action) - filed rate doctrine - good faith - prior pending action - sovereign immunity - truth (in defamation actions) - suicide (in accident or some benefits actions) - adverse possession (in trespass action) - mutual acquiescence in boundary (in trespass action) - statutory immunity (under applicable state or federal law) - unconstitutional (relating to statute allegedly violated) - insanity (normally in criminal context, but may have some application in civil suits linked to criminal acts) - self-defense (in assault, battery, trespass actions) - permission/invitation (in assault, battery, trespass actions) - agency - Section 2-607 UCC acceptance of goods, notification of defect in time or quality within reasonable time - at-will employment - breach of contract - hindrance of contract - cancellation of contract/resignation - circuitry of action - discharge (other than bankruptcy) - election of parties - election of remedies - joint venture - lack of authority - mutual mistake - no government action - privilege - reasonable accommodation - retraction - safety of employee (ADA) - statutory compliance - no damages (where required element of pleading) - termination of employement - undue burden (ADA) - wrong party - implied repeal of statute (see In re: Stock Exchanges Options Trading Antitrust Litigation, 317 F.3d 134 (2d. Cir. 2003) (hat tip Bill Shea) - failure to take advantage of effective system to report/stop harassment (in Title VII actions, called the Faragher-Ellerth defense) (see Jones v. D.C. Dept. of Corrections, 429 F.3d 276 (D.C. Cir. 2005) (hat tip Bill Shea) - Noerr-Pennington defense (antitrust) (a Sherman Act defendant can raise the affirmative defense of right to petition for redress, even if they use that right to try to gain an anti-competitive advantage). See Noerr-Pennington Doctrine (2009), ABA Section of Antitrust Law, at p.107. (hat tip Bill Shea)- fair use (copyright). See, e.g., Campbel, aka Skywalker, et al. v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 590 (1994). (hat tip Bill Shea) - Same decision defense (employer would still have fired employee for lawful reasons even if the actual firing was for a mix of lawful and unlawful reasons) (Mt. Healthy City School Dist. Bd. of Ed. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977)) (hat tip Bill Shea) - ignorance of the law. Ignorance of the law is rarely a defense to liability, but if proven, ignorance that racial discrimination violates federal law may be a defense to punitive damages in Title VII cases. See, e.g. Alexander v. Riga, 208 F.3d 419, 432 (3d Cir. 2000) (hat tip Bill Shea) - business judgment rule (hat tip Iain Johnston) - claim of right (defense to element of intent required to prove theft) - Jeff Vail is a Colorado business litigation attorney at The Law Office of Jeff Vail LLC. This post is part of my Colorado litigation checklist approach to litigation knowledge management and litigation strategy. |

LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose.