Add this feed to your friends list for news aggregation, or view this feed's syndication information.

LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose.

| Sunday, February 22nd, 2026 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 10:17 pm | A Divisibility-Based Method to Find Non-Torsion Integer Points on an Elliptic Curve I propose a method to detect possible generator (non-torsion) integer points on an elliptic curve of the form

$$y^2=x^3+Ax+B$$

Suppose the curve has at least three non-torsion integer points

$$(x_1,y_1),(x_2,y_2),(x_3,y_3)$$

Where also satisfying the following condition.

$$x_1+x_2+x_3=s^2$$

Proposed Method

$$|A^2 - 2B| \equiv 0 \pmod{m}$$

Find all the divisors values of '$m$'

$$m_1,m_2,m_3,....,m_n$$

Consider the following candidate values for '$x$'

$$±1,±(A^2-2B),±m_1,±m_2,±m_3,....,±m_n$ Empirically, at least one of these values appears to satisfy the curve and produce an integer point. For example $$y^2=x^3-12x+65$$ $$|12^2 - 2×65| \equiv 0 \pmod{m}$$ $$ 14 \equiv 0 \pmod{m}$$ Here $$m_1=2,m_2=7$$ Now we will get $8$ solutions $$±1,±14,±2,±7$$ After substituting all the values on the place of '$x$' you will find $$x=7,x=2,x=-2 $$ These values are satisfying the elliptic curve. Questions: 1.Is this divisibility-based method already known in the literature on elliptic curves?

|

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 10:17 pm | Is every palindromic even number the sum of a palindromic prime and at most 2 squares? I learnt that a theorem of Landau (1960) asserts that the number of sums of two squares up to $x$ is asymptotically $\frac{K}{\sqrt{\log x}}$ where $K=0.7642236...$ is the so called Landau-Ramanujan constant. As I'm obsessed with symmetry, a Goldbach-type problem came to my mind: knowing that every prime $p\equiv 1\pmod 4$ is the sum of two squares in an essentially unique way, one may ask if every palindromic even number is the sum of a palindromic prime and at most 2 squares. Note that such a palindromic prime greater than $12$ has an odd number of digits, otherwise it would be a multiple of $11$. No counterexample up to $10^{12}$ has been found. Is this provable and if not, can a sensible heuristics back up numerical evidence? |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:03 pm | Quantization of symplectic vector space and choice of lagrangian subspaces My question is related to Geometric Quantization. I don't undrestand the philosophy of following assertion

|

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:33 pm | Double estimates relating Ruzsa distance and doubling constant I am trying to solve the following exercise (2.3.16) from Tao-Vu book.

My approach: i) We note that the first inequality can be written as follows: $$\dfrac{|A\cup B+A\cup B|}{|A\cup B|}\leq \dfrac{|A-B|}{|A|^{1/2}|B|^{1/2}}+2\dfra Therefore, $$\dfrac{|A\cup B+A\cup B|}{|A\cup B|}\leq 2\dfrac{|A-B|^4}{|A|^2|B|^2}+\dfrac{|A+B| ii) The second inequality is equivalent to $|A-B|\leq |A\cup B+A\cup B|$ and I have no idea how to prove that. I was trying to prove using Ruzsa triangle inequality but I failed. It would be great to see how to solve this exercise. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 pm | Best practices for citing and documenting certified computations in a mathematics paper I am writing a paper in which one part of the proof uses a certified computation (for example, interval arithmetic, exact arithmetic checks, or machine-checkable certificates), and I would like to present it in a way that is clear to referees and future readers. What are current best practices for documenting and citing such computations in a mathematics paper? For example:

Examples of papers or references with especially good practice would also be appreciated! |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 7:32 pm | Summary of the current progress on Navier-Stokes existence and smoothness problem As a computational fluid dynamics engineer with a background in applied mathematics, I have a great deal of interest in the Navier-Stokes existence and smoothness problem. I don't expect to solve it myself (obviously), but I would like to at least be up to date with the current progress on this problem. The Wikipedia page is rather brief and I feel that there is probably quite a lot they are missing. My questions are basically as follows:

There are a number of good textbooks on this topic, by Temam, Rieusset, and others, but they are arranged primarily by topic. I'd like it if someone could give the most significant results known so far, arranged more or less chronologically. The reason for this is that at some point I would like to give a seminar to the rest of my company on the topic, and I think a chronological arrangement helps convey more of a "story". Not sure if this question is fully appropriate for this site, but, I'm giving it a try. Thanks! |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 7:32 pm | How to estimate an integral by the variation and upper bound of the integrand? Suppose that $f$ is a continuous function on $\mathbb{R}$. I want to estimate the definite integral $$ I:= \int_{0}^a [f(x)-f(0)]dx $$ by the upper bound $M = \sup_{x\in[0,a]}|f(x)|$ and the variation $V_f(x,\delta):=\sup_{y\in [x,x+\delta]}|f(x)-f(y)|$ I have a small $\delta>0$ and eventually make $\delta \rightarrow 0$. And fix a positive constant integer $k$. Then the part

$$I_1:=\int_0^{k\delta} [f(x)-f(0)]dx$$

can be precisely estimated by

$$ |I_1|\leq \sum_{i=0}^{k-1}\int_{i\delta}^{(i+1)\de However, if I have a constant $0<c<a$ and don't do anything to it later, then the variation is not the best choice for the part $$ I_2 := \int_{c}^a [f(x)-f(0)]dx$$ because $x$ is far away from $0$. So, it may be the best choice to estimate by the upper bound. $$ I_2 \leq 2(a-c)M. $$ The question is what is the best estimation for the rest interval $$ I_3 := \int_{k\delta}^{c}[f(x)-f(0)] ?$$ It seems either the variation or the upper bound is not the best choice. That is, they both overestimate $|I_3|$. Of course, if $f$ satisfies some Holder continuity, $|I_3|$ can be estimated well. Here, nevertheless, I wonder what estimation we can do for the most general continuous functions. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 6:17 pm | Closing gap between lower and upper bounds There is a set $S$ and a set $V$. Each element $s$ has value $\pi_s\geq 0$ and a parameter $\alpha_s\in [0,1]$. There is a bipartite graph $G=(S,V,E)$, in which an edge $(s,v)\in E$ indicates that $v$ is allocates $\sigma_v^s\geq 0$ to $s$. Elements in $N_G(s)$ allocate to $s$. We say service $s$ can attack by a subset of $A\subseteq N_G(s)$, when they own more than $\alpha_s$ share of the total allocation in $N_G(s)$, i.e., $\frac{\sum_{v\in A}\sigma^s_v}{\sum_{v\in N_G(s)}\sigma^s_v}\geq \alpha_s$. We say that an attack is profitable if the total allocation in $A$ is lower than the value $\pi_s$. Element $s$ is secure if there is no profitable attack to $s$. Assume all elements in $S$ are secure. Next, assume all elements in $V$ aggregate their allocations into one value, $\sigma_v:=\sum_{s\in N_G(v)}\sigma_v^s$. This aggregate graph, is secure if there is no subset of $V$ that can profitably attack any subset of $S$. The profit of attacking a subset of $S$ is a sum of values in this set. Elements are using aggregate values, $\sigma_v$, for the attack. We minimize the extra value required to add to $\sigma_v$ values so that the aggregate graph is secure, relative to the original total value in $V$, $\sum_{v\in V} \sigma_v$, denoted by PoSS. In this paper, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2505.24440, we show that there are instances of $G$ where $PoSS(G)$ reaches arbitrarily close values to $1$, and $PoSS(G)$ is upper bounded by $\max_s{d_G(s)}-1$, which leaves a wide gap between $1$ and $\max_s{d_G(s)}-1$. I am interested in improving these bounds. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

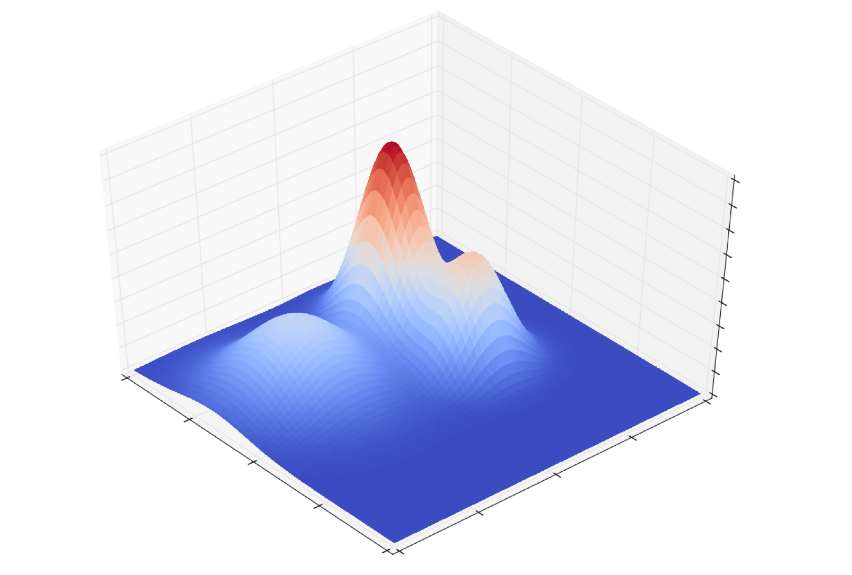

| 6:17 pm | Local maxima of the sum of Gaussian functions in *multiple dimensions* are always strict local maxima - prove/disprove/prove conditionally? This is a follow up of the question in one dimension, that asked to show that the all the maxima of the sum of Gaussian $$f_n(x):= \sum_{i=1}^{n}e^{-(x-x_i)^2}, x_1 < x_2 < \dots < x_n$$ are strict local maxima, i.e. there's a punctured neighborhood $U*$ around each local maxima $x*$, so that the $\forall x \in U*, f(x)< f(x*),$ (instead of $f(x)\le f(x*).$)** The accepted answer used the identity theorem for real analytic function $f_n'$ to show that indeed all the critical points of $f_n$ are isolated, which, combined with the fact that the critical points must lie in $[x_1,x_n],$ proved that the critical points were finite in number and thus the answer proved that in one dimension, the local maxima of $f_n$ are strict local maxima. This question is its generalization to higher dimensions $x_i, x \in \mathbb{R}^p.$ So here we consider: $$f_n(x):= \sum_{i=1}^{n}e^{-||x-x_i||^2}.$$ Note that, here the critical points $x*$ will be given by: $$\nabla{f_n}=0$$ $$ \implies \boxed{ x*=\frac{ \sum_{i=1}^{n}e^{-||x*-x_i||^2} x_i }{ \sum_{i=1}^{n}e^{-||x*-x_i||^2} } },$$ implying that $x*$ lie in the convex hull $C$ of $\{x_1\dots x_n\},$ just like in the one dimensional case, they lied in $[x_1,x_n]$ (see above or the link to the one dimensional case given above). But this time, unlike one dimensional case, we cannot guarantee using the identity theorem that the zeros of the $\nabla{f_n}$ are isolated, because in higher dimensions, the usual identity theorem for real analytic function doesn't hold. We do know that zeros of the gradient has zero Lebesgue measure, thanks to this post and the references therein; but this doesn't prove that the the zeros are isolated, unlike one dimensional case. Here's an image that shows a linear combination of three, two dimensional Gaussians: It seems to me that its local maxima are all strict local maxima. I did an image search but never found any image otherwise. So is there a proof that the local maxima of $f_n$ are strict? Thought: (1) Since $0< f_n(x) \le n,$ I'm thinking if we can explore the topology of $y \in (0,n], f_n^{-1}(y)$. It seems to me that $\forall y \in (0,n], f_n^{-1}(y)$ consists of the disjoint union of at most $n$ points or hyperspheres $S^{p-1}\subset \mathbb{R}^p.$ whose supporting hyperplanes are orthogonal to the $x_n$ axis: so for example when $p=2, f_n^{-1}(y)$ is a disjoint union of at most $n$ points or horizontal circles whose supporting planes are orthogonal to the $x_3$ axis. If we can show that, then it'll show that for the local maximum $x*$ with local maximum value $y*, f_n^{-1}(y*)$ is a point or a disjoint union of points, as otherwise it'd be a disjoint union of hyperspheres orthogonal to the axis $x_{n+1}$ , which would mean that these hyperspheres can't come arbitrarily close to $x*,$ proving the local max is a strict one. Not sure if we need Morse theory to prove this? Thought: (2) I'm not familiar with a lot of fixed point theory, but I see that the critical points are the fixed points of the map from $\Phi: \mathbb{R}^p\to \mathbb{R}^p, C\to C:$ (see the boxed equation above) $$\Phi: x \mapsto \frac{ \sum_{i=1}^{n}e^{-||x-x_i||^2} x_i }{ \sum_{i=1}^{n}e^{-||x-x_i||^2} } $$ Now can we say something about the above map $\Phi$ that guarantees that its fixed points are isolated? I don't know, but I'm looking at this and this question on MSE that deal with isolatedness and thus finitely many Lefscetz fixed points on a compact manifold, and in our case, we know that these fixed points of $\Phi: \mathbb{R}^p\to \mathbb{R}^p$ are on a compact manifold with boundary and corners, namely $C,$ the convex hull of $\{x_1, x_2 \dots x_n\}.$ So it seems to me that all we may need to show is that: $\Phi:C \to C$ is Lefschetz, i.e. $D\Phi_{x*}:\mathbb{R}^p\to \mathbb{R}^p$ does not have the eigenvalue $1.$ Can we show that, probably? Thought (3) [after the suggestion in the first comment] We can try proving the positive definiteness of the Hessian at the critical point $x*$,, where the Hessian matrix $H(x)$ at $x$ is as follows: $$H(x)={\sum_{i=1}^{n}(-2I+4{(x-x_i)(x-x |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 5:46 pm | Exponentiating cardinal characteristics Consider the following statements:

In $\mathsf{ZFC+CH}$, both statements are true, so each of them is consistent. Question. Is one of $(\mathrm{S1}), (\mathrm{S2})$ a theorem in $\mathsf {ZFC}$? |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 5:17 pm | Groups with a certain character-theoretic property Let $G$ be a finite group and let $\operatorname{Irr}(G)$ denote the set of all inequivalent, irreducible characters of $G$. Suppose $G$ be a group such that $\chi(g)+\chi(g^{-1})\in\mathbb{Z}$ for every $\chi\in\operatorname{Irr}(G)$ and $g\in G$. I want to know whether there is a complete classification of groups satisfying this property? For example, every rational group $G$ (groups in which $\chi(g)\in\mathbb{Z}$ for all $\chi\in\operatorname{Irr}(G)$ and $g\in G$) satisfies this property. Also, $\mathbb{Z}_3$ and $A_4$ (which are not rational groups) satisfy this. Any help would be appreciated. Originally posted to MathStackexchange, where there's been no answer after five days: https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/5 |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 4:52 pm | Linear logic with storage preserving positives Has anyone studied a version of linear logic in which the storage modality $!$ preserves the positive connectives and quantifiers $\otimes,\oplus,\exists$? That is, such that we have $!(A\otimes B) = !A \otimes !B$ and $!(A\oplus B) = !A \oplus !B$ and $!\exists x. A = \exists x.!A$. It seems that there ought to be a reasonable sequent calculus for such a theory, e.g. using a "modal context zone" as in Girard's LU or Pfenning's LV enhanced with left rules that allow introducing $\otimes,\oplus,\exists$ in the modal zone. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 4:52 pm | Applied examples of (non)uniformly hyperbolic and/or ergodic systems I try to give reference to completely applied examples of (non)uniformly hyperbolic and/or ergodic systems. With completely applied I don't mean an irrational rotation on the torus but from other branches like biology, astronomy, physics, engineering, computer science... The only example that comes to my mind is the Lorentz-gas. I also thought about an application of the N-body problem. To broaden the scope a little bit I would also take examples from known 'chaotic' systems in nature. Thanks in advance for any input |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 3:32 pm | Nonattainment of minimal energy among smooth competitors in Dirichlet problem Let $M$ be a compact Riemannian manifold with boundary $\partial M \ne \emptyset$ and dimension at least $2$, and let $N$ be a compact Riemannian manifold with no boundary of dimension at least $2$ that is isometrically embedded into $\mathbb R^p$ for some $p \ge 2$. Suppose that $v \in C^\infty (\partial M ; N )$. Let $\mathcal A _ v ^\infty = \{u \in C^\infty (M;N) : u|_{\partial M} = v \}$. My question is whether there exist known examples of such $M,N,v$ so that $\mathcal A_v^\infty \ne \emptyset$ and so that $\inf_{ \mathcal A^\infty_v} \mathcal E$ is not attained by any $u \in \mathcal A_v^\infty$, where $\mathcal E$ denotes the Riemannian Dirichlet energy functional. I am aware of the following two related results. Let $\mathcal A_v = \{u \in W^{1,2}(M;N) : \mathrm{Tr}_{\partial M} (u) = v\} \supseteq \mathcal A_v^\infty$. (i) In the case $M = \bar B^3$ and $N = S^2 \subseteq \mathbb R^3$, there exist (many) $v: S^2 \to S^2$ smooth of degree $0$ (so $\mathcal A _v^\infty \ne \emptyset$) with $\inf_{\mathcal A _v } \mathcal E < \inf_{\mathcal A _v ^\infty} \mathcal E$. Thus here no smooth competitor can be minimising among Sobolev competitors. This is proved, for example, in https://arxiv.org/abs/1406.0601. This does not rule out smooth competitors that are minimising among smooth competitors however. (ii) For $M = \bar \Omega$ where $\Omega \subseteq \mathbb R^3$ is open, bounded, and nonempty, and $N = S^2$, for $v \in C^0 (\partial \Omega; S^2) \cap H^1(\partial \Omega ; S^2)$ of degree $0$, F. Bethuel, H. Brezis & J. M. Coron considered it an open question in Relaxed Energies for Harmonic Maps in 1990 whether or not $\mathcal \inf_{\mathcal A _v \cap C^0 (\bar \Omega ; S^2)} \mathcal E$ is attained in general. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 2:19 pm | Twisted moments of Dirichlet $L$-functions in $t$-aspect The twisted second and fourth moments of the Riemann zeta function are known, that is asymptotics for

$$\int_1^T|\zeta(\tfrac{1}{2}+it)|^2|M(\t I want to know if there are analogous results for the case where $\zeta(1/2+it)$ is replaced by $L(1/2+it,\chi)$? There are twisted moment results for Dirichlet $L$-functions, but I can unfortunately only find references for twisted moments in the $q$ aspect, whereas I am interested in the $t$-aspect. Any references would be much appreciated! |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 1:01 pm | Connecting efficiently metrics on a surface with lower curvature bound Let $S$ be a closed surface and $\mathcal M$ be the space of metrics on $S$ equipped with the Lipschitz distance $d$. (Say, up to isometry isotopic to the identity and $d$ is also defined with respect to that.) Pick $k \in \mathbb R$ and let $\mathcal M_k \subset \mathcal M$ be the subspace of metrics with curvature bounded below by $k$. Given $g_0, g_1 \in \mathcal M_k$, how to connect them efficiently in $\mathcal M_k$? More explicitly, how to construct a path $g_t \in \mathcal M_k$, $0 \leq t \leq 1$, such that the length of $g_t$ with respect to $d$ is bounded in terms of $d(g_0, g_1)$? I am interested in general length metrics and curvature bound in terms of Alexandrov, but to begin, we can, of course, assume that everything is smooth. (To be very fair, I am interested in the case of hyperbolic cone-metrics with cone-angles $<2\pi$ and admitting the same geodesic triangulation. In such case, the space of hyperbolic cone-metrics admitting a triangulation $T$ is naturally a convex cone in $\mathbb R^{E(T)}$, where $E(T)$ is the set of edges of $T$. But the subset of metrics with cone-angles $<2\pi$ is not convex and even in this simply-looking case I do not know how to proceed.) Such a bound can (and probably should) involve some other global parameters of $g_0$ and $g_1$ like their diameters, areas, etc., but I am looking for a bound using as few other parameters as possible. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 1:01 pm | Does continuity of the gradient norm imply continuity of the gradient? Let $f: \mathbb R^n \to \mathbb R$ be everywhere differentiable. Suppose $|\nabla f|$ is continuous. Does it follow that $\nabla f$ is continuous? |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 11:47 am | Joshua Lederberg's influence on graph theory Joshua Lederberg received a the Nobel price in medicine in 1958 and he was a major contributor to the Stanford DENDRAL software expert system that

In that expert system non-Hamiltonicity plays a central role and Lederberg devised a method of generating non-Hamilton graphs by means of a 9-vertex "gadget" and with it constructed a planar cubic and biconnected non-Hamiltonian graph with 18 vertices and also the better known Barnette-Bosák-Lederberg graph that is triply connected. Question:

A search for "Lederberg" on MO didn't succeed and trying to find a definition or illustration of Lederberg's 18-vertex graph is also a frustrating task, even with AI assistance. I'm not sure if the 9-vertex gadget or the 18-vertex Lederberg graphs are known to the house of graphs |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:49 am | Do presheaves of complexes with term-wise descent satisfy descent as well? For $i\geq 0$, let $A_i$ be a functor from commutative rings to abelian groups satisfying descent for some topology, e.g. Zariski. Let $d_i:A_i\to A_{i+1}$ be a natural transformation such that $d_i\circ d_{i+1}=0$. This way, we get a functor from commutative rings to cochain complexes $$C=[A_0\xrightarrow{d_0} A_1 \xrightarrow{d_1} A_2 \to \cdots]$$ Let $D(\mathbb{Z})$ be derived category of $\mathbb{Z}$-modules, as a stable $\infty$-category. Does the induced functor $$C:\{\text{Rings}\}\longrightarrow D(\mathbb{Z})$$ satisfies descent for the topology, here Zariksi? I have essentially two worries :

|

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 7:01 am | Best known bounds for the maximal deviation of squarefree counts in short intervals Let \begin{equation} Q(x,H):=\sum_{x<n\le x+H}\mu^2(n)-\frac{6}{\pi^2}H. \end{equation} I am interested in the maximal deviation \begin{equation} M(X,H):=\sup_{1\le x\le X}|Q(x,H)|. \end{equation} What are the best known upper bounds (and, if available, lower bounds or omega-results) for $M(X,H)$ as $X\to\infty$, especially in the regime $H=X^\theta$ with $0<\theta<1$? I would be particularly grateful for:

I am aware of the average density $6/\pi^2$, but I am specifically asking about the maximal short-interval discrepancy. |

LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose.