[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Sunday, April 24th, 2016

| Time | Event | ||

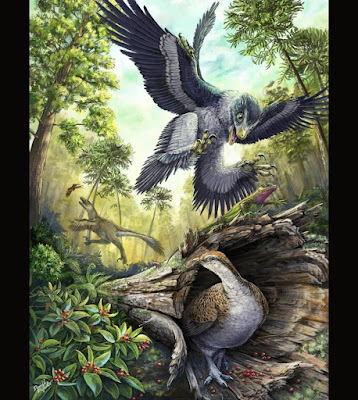

| 12:33a | [PaleoEcology / Paleontology • 2016] Dental Disparity and Ecological Stability in Bird-like Dinosaurs Prior to the End-Cretaceous Mass Extinction Highlights • Tooth shape disparity in small maniraptoran dinosaurs is examined in the Cretaceous • Results show stability and sudden extinction in this guild at the end of the Cretaceous • Groups are mostly static in shape space except for larger size in the early Maastrichtian • Evolution of an edentulous beak and granivory may have been key to the survival of birds Summary The causes, rate, and selectivity of the end-Cretaceous mass extinction continue to be highly debated. Extinction patterns in small, feathered maniraptoran dinosaurs (including birds) are important for understanding extant biodiversity and present an enigma considering the survival of crown group birds (Neornithes) and the extinction of their close kin across the end-Cretaceous boundary. Because of the patchy Cretaceous fossil record of small maniraptorans, this important transition has not been closely examined in this group. Here, we test the hypothesis that morphological disparity in bird-like dinosaurs was decreasing leading up to the end-Cretaceous mass extinction, as has been hypothesized in some dinosaurs. To test this, we examined tooth morphology, an ecological indicator in fossil reptiles, from over 3,100 maniraptoran teeth from four groups (Troodontidae, Dromaeosauridae, Richardoestesia, and cf. Aves) across the last 18 million years of the Cretaceous. We demonstrate that tooth disparity, a proxy for variation in feeding ecology, shows no significant decline leading up to the extinction event within any of the groups. Tooth morphospace occupation also remains static over this time interval except for increased size during the early Maastrichtian. Our data provide strong support that extinction within this group occurred suddenly after a prolonged period of ecological stability. To explain this sudden extinction of toothed maniraptorans and the survival of Neornithes, we propose that diet may have been an extinction filter and suggest that granivory associated with an edentulous beak was a key ecological trait in the survival of some lineages. Derek W. Larson, Caleb M. Brown and David C. Evans. 2016. Dental Disparity and Ecological Stability in Bird-like Dinosaurs Prior to the End-Cretaceous Mass Extinction. Current Biology. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.039 Fossil teeth suggest that seeds saved bird ancestors from extinction http://esciencenews.com/node/1250215 Why did birds live while dinosaurs died? It’s a seedy story, researchers say /via @globeandmail http://www.theglobeandmail.com/technolog Fossil teeth suggest that seeds saved bird ancestors from extinction https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/20 | ||

| 7:17p | [Mammalogy • 2016] Phylogenetic Position of A Monotypic Ethiopian Endemic Rodent genus Megadendromus (Rodentia, Nesomyidae)

Abstract The taxonomic and phylogenetic position of the Nikolaus’s African climbing mouse (Megadendromus nikolausi), formerly known only from four specimens, remained for a long time ambiguous. Here, we report, for the first time, the phylogenetic analysis of this species using mitochondrial (cytochrome b) and nuclear (interphotoreceptor binding protein) gene sequences obtained from a new specimen recently caught in the Bale Mountains in south-eastern Ethiopia. Our analyses strongly suggest that the Nikolaus’s climbing mouse does not belong to a distinct monotypic genus, but to the genus Dendromus. The first karyotype description of this enigmatic Ethiopian endemic is presented. The diploid set comprises 18 pairs of bi-armed chromosomes, 2N=36, one of the lowest diploid numbers reported for the genus Dendromus (2N=30–52). Moreover, the phylogenetic analysis reveals that another very distinctive Ethiopian endemic, Dendromus lovati, sometimes placed in a subgenus Chortomys, occupies an internal position within Dendromus s.s. The results suggest that the Ethiopian Plateau is an important center of high diversity and adaptive radiation for the genus Dendromus. The conservation status of M. nikolausi is assessed. Keywords: Dendromurinae; Ethiopia; karyotype; Megadendromus; phylogeny. Leonid A Lavrenchenko, R. S. Nadjafova, Afework Bekele, Tatiana Mironova and Josef Bryja. 2016. Phylogenetic Position of A Monotypic Ethiopian Endemic Rodent genus Megadendromus (Rodentia, Nesomyidae). Mammalia. DOI: 10.1515/mammalia-2015-0148 |

| << Previous Day |

2016/04/24 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |