[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, June 20th, 2016

| Time | Event | ||

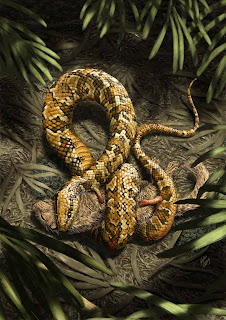

| 4:47a | [Paleontology • 2015] Tetrapodophis amplectus • A Four-legged Snake from the Early Cretaceous of Gondwana Snakes are a remarkably diverse and successful group today, but their evolutionary origins are obscure. The discovery of snakes with two legs has shed light on the transition from lizards to snakes, but no snake has been described with four limbs, and the ecology of early snakes is poorly known. We describe a four-limbed snake from the Early Cretaceous (Aptian) Crato Formation of Brazil. The snake has a serpentiform body plan with an elongate trunk, short tail, and large ventral scales suggesting characteristic serpentine locomotion, yet retains small prehensile limbs. Skull and body proportions as well as reduced neural spines indicate fossorial adaptation, suggesting that snakes evolved from burrowing rather than marine ancestors. Hooked teeth, an intramandibular joint, a flexible spine capable of constricting prey, and the presence of vertebrate remains in the guts indicate that this species preyed on vertebrates and that snakes made the transition to carnivory early in their history. The structure of the limbs suggests that they were adapted for grasping, either to seize prey or as claspers during mating. Together with a diverse fauna of basal snakes from the Cretaceous of South America, Africa, and India, this snake suggests that crown Serpentes originated in Gondwana. Martill, D.M., H. Tischlinger and N.R. Longrich. 2015. A Four-legged Snake from the Early Cretaceous of Gondwana. Science. 349(6246): 416-419. DOI: 10.1126/science.aaa9208 ResearchGate.net/publication/280389042_A http://eprints.port.ac.uk/18465/1/A_four Four-Legged Snake Shakes Up Squamate Family Tree - Or Does It? - Science Sushi http://bit.ly/1UJeeOS Caldwell, M. W., Nydam, R. L., Palci, A. and Apesteguía, S. 2015. The oldest known snakes from the Middle Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous provide insights on snake evolution. Nature communications. 6. DOI: 10.1126/science.aaa9208 | ||

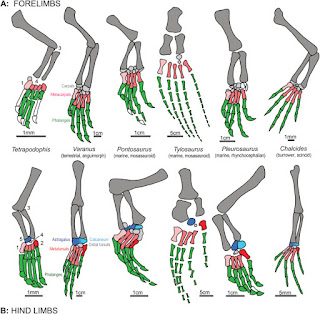

| 4:54a | [Paleontology • 2016] Aquatic Adaptations in the Four Limbs of the Snake-like Reptile Tetrapodophis from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil Abstract The exquisite transitional fossil Tetrapodophis – interpreted as a stem-snake with four small legs from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil – has been widely considered a burrowing animal, consistent with recent studies arguing that snakes had fossorial ancestors. We reevaluate the ecomorphology of this important taxon using a multivariate morphometric analysis and a reexamination of the limb anatomy. Our analysis shows that the body proportions are unusual and similar to both burrowing and surface-active squamates. We also show that it exhibits striking and compelling features of limb anatomy, including enlarged first metapodials and reduced tarsal/carpal ossification – that conversely are highly suggestive of aquatic habits, and are found in marine squamates. The morphology and inferred ecology of Tetrapodophis therefore does not clearly favour fossorial over aquatic origins of snakes. Keywords: Squamata; Ophidia; Serpentes; Evolution; Cretaceous; Paleoecology Conclusions Tetrapodophis does not clearly fall into any of the known ecological categories, but the presence of the limb features discussed above is difficult to explain as anything but holdovers from a more aquatically-adapted ancestor. Tetrapodophis therefore represents a truly enigmatic animal, combining the body proportions of an elongate squamate with the limbs of a swimmer (or former swimmer). The precise ecology of this iconic fossil will thus continue to be debated. Perhaps the reality lies in between, and Tetrapodophis may have been both fossorial and aquatic, a lifestyle exhibited by some living snakes such as neotropical pipesnakes (Anilius) (e.g. Murphy, 2010). Michael S.Y. Lee, Alessandro Palci, Marc E.H. Jones, Michael W. Caldwell, James D. Holmes and Robert R. Reisz. 2016. Aquatic Adaptations in the Four Limbs of the Snake-like Reptile Tetrapodophis from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. Cretaceous Research. DOI: 10.1016/j.cretres.2016.06.004 Did snakes evolve from ancient sea serpents? http://phy.so/385370720 via @physorg_com | ||

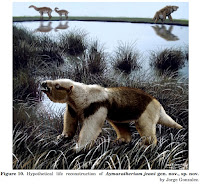

| 5:47p | [PaleoMammalogy • 2016] Aymaratherium jeani • A New Nothrotheriid Xenarthran from the early Pliocene of Pomata-Ayte (Bolivia): New Insights into the Caniniform–Molariform Transition in Sloths

Tardigrade xenarthrans are today represented only by the two tree sloth genera Bradypus and Choloepus, which inhabit the Neotropical rainforests and are characterized by their slowness and suspensory locomotion. Sloths have been recognized in South America since the early Oligocene. This monophyletic group is represented by five clade straditionally recognized as families: Bradypodidae, Megalonychidae, Mylodontidae (†), Megatheriidae (†) and Nothrotheriidae (†). A new nothrotheriid ground sloth represented by a dentary and several postcranial elements, Aymaratherium jeani gen. nov., sp. nov., from the early Pliocene locality of Pomata-Ayte (Bolivia) is reported.This small- to medium-sized species is characterized especially by its dentition and several postcranial features. It exhibits several convergences with the ‘aquatic’ nothrotheriid sloth Thalassocnus and the giant megatheriid ground sloth Megatherium (M.) americanum, and is interpreted as a selective feeder, with good pronation and supinationmovements. The tricuspid caniniform teeth of Aymaratherium may represent a transitional stage between the caniniform anterior teeth of basal megatherioids and basal nothrotheriids (1/1C-4/3M as in Hapalops or Mionothropus) and the molariform anterior teeth of megatheriids (5/4M, e.g. Megatherium). To highlight the phylogenetic position of this new taxon among nothrotheriid sloths, we performed a cladistic assessment of the available dental and postcranial evidence. Our results, derived from a TNT treatment of a data matrix largely based on a published phylogenetic data set, indicate that Aymaratherium is either sister taxon to Mionothropus or sister to the clade Nothrotheriini within Nothrotheriinae. They further support the monophyly of both the Nothrotheriinae and the Nothrotheriini, as suggested previously by several authors. ADDITIONAL KEYWORDS: Anatomy; Bolivia; early Pliocene; Nothrotheriidae; phylogeny; Pilosa; Xenarthra. SYSTEMATIC PALAEONTOLOGY XENARTHRA COPE, 1889 PILOSA FLOWER, 1883 TARDIGRADA LATHAM&DAVIES IN FORSTER, 1795 NOTHROTHERIIDAE AMEGHINO, 1920 Etymology. In reference to the Aymara (Aymar aru), a native ethnic group and language from the Andes, from where the specimens were recovered; and,the specific epithet for Jean Joinville Vacher (successively Director of the French Institute of Andean Studies – IFEA, Advisor of the Institute for Development Research – IRD in Bolivia, Advisor of Regional Cooperation for Andean Countries of the French Embassy during 2000/2012, and currently Assistant to General Executive Officer for Science of the IRD) for his friendship and constant support forpalaeontological investigations over the years. Francois Pujos, Gerry De Iuliis, Bernardino Mamani Quispe, Sylvain Adnet, Ruben Andrade Flores, Guillaume Billet, Marcos Fernandez-Monescillo, Laurent Marivaux, Philippe Münch, Mercedes B. Prámparo and Pierre-Olivier Antoine. 2016. A New Nothrotheriid Xenarthran from the early Pliocene of Pomata-Ayte (Bolivia): New Insights into the Caniniform–Molariform Transition in Sloths. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. DOI: 10.1111/zoj.12429 |

| << Previous Day |

2016/06/20 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |