[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Saturday, January 13th, 2018

| Time | Event | ||||||

| 6:47a | [Bryophyta • 2018] Sphagnum incundum • A New Species in Sphagnum subg. Acutifolia (Sphagnaceae) from Boreal and Arctic Regions of North America

Abstract We describe Sphagnum incundum in Sphagnum subgenus Acutifolia (Sphagnaceae, Bryophyta). We used both molecular and morphological methods to describe the new species. Molecular relationships with closely related species were explored based on microsatellites and nuclear and plastid DNA sequences. The morphological description is based on qualitative examination of morphological characters and measurements of leaves and hyalocysts. Morphological characters are compared between closely related species. The results from Feulgen densitometry and microsatellite analysis show that S. incundum is gametophytically haploid. Molecular analyses show that it is a close relative to S. flavicomans, S. subfulvum and S. subnitens, but differs both genetically and in morphological key characters, justifying the description of Sphagnum incundum as a new species. The new peatmoss is found in North America along the western coast of Greenland, in Canada from Quebec and Northwest Territories, and Alaska (United States). The new species has a boreal to arctic distribution. Keywords: Bryophytes, Sphagnaceae Sphagnum incundum Flatberg & Hassel sp. nov. Diagnosis:— Sphagnum incundum is in macro-morphology recognized by slender shoots with predominantly brownorange to purple-red capitula and straight and non-recurved leaves on innermost capitulum branches on dry plants. In micro-morphology, it is foremost recognized by narrowly lingulate stem leaves with acute to acute-obtuse apices, strongly S-shaped stem leaf hyalocysts with common occurrence of faint fibrils in distal leaf-parts, and divergent branch leaf hyalocysts on distal end convex surfaces with pores usually occupying between 1/3 and 1/2 of cell width. The new species is gametophytic haploid and closely allied morphologically to S. flavicomans, S. subfulvum, and S. subnitens. Etymology:— The specific epithet is derived from the Latin adjective incundus = pleasant, agreeable, delightful. Distribution:— West Greenland, Canada in Quebec, Nunavut and North West territories, and U.S.A in Alaska. Currently known from the northern boreal to middle arctic vegetation zone. Ecology:— Sphagnum incundum in arctic localities in West Greenland, and Nunavik, Quebec, occurs in arctic mires on shallow peat in intermediate and rich fens, partly forming small mats and low cushions on gently sloping, soligenous mire, partly growing in small patches on lawn and carpet mire. The most commonly associated sphagna in both regions were S. concinnum (Berggr.) Flatberg (2007: 88), S. squarrosum, S. teres and S. warnstorfii Russow (1886: 315). In the boreal Anchorage area, Alaska, it was found growing in a large fen mire on high lawn patches in topogenous, varyingly intermediate to rich fen vegetation, associated with S. papillosum Lind. (1872: 280), S. subfulvum and S. miyabeanum Warnstorf (1911: 321). In Bethel area, Alaska, it occurred scattered on intermediate fen lawns in tundra mire. Magni Olsen Kyrkjeeide, Kristian Hassel, Blanca Shaw, A. Jonathan Shaw, Eva M. Temsch and Kjell Ivar Flatberg. 2018. Sphagnum incundum A New Species in Sphagnum subg. Acutifolia (Sphagnaceae) from Boreal and Arctic Regions of North America. Phytotaxa. 333(1); 1–21. DOI: 10.11646/phytotaxa.333.1.1 | ||||||

| 2:29p | [Herpetology • 2017] Arboreality Constrains Morphological Evolution but Not Species Diversification in Vipers

Abstract An increase in ecological opportunities, either through changes in the environment or acquisition of new traits, is frequently associated with an increase in species and morphological diversification. However, it is possible that certain ecological settings might prevent lineages from diversifying. Arboreality evolved multiple times in vipers, making them ideal organisms for exploring how potentially new ecological opportunities affect their morphology and speciation regimes. Arboreal snakes are frequently suggested to have a very specialized morphology, and being too large, too small, too heavy, or having short tails might be challenging for them. Using trait-evolution models, we show that arboreal vipers are evolving towards intermediate body sizes, with longer tails and more slender bodies than terrestrial vipers. Arboreality strongly constrains body size and circumference evolution in vipers, while terrestrial lineages are evolving towards a broader range of morphological variants. Trait-dependent diversification models, however, suggest similar speciation rates between microhabitats. Thus, we show that arboreality might constrain morphological evolution but not necessarily affect the rates at which lineages generate new species. KEYWORDS: speciation, divergent selection, snakes, Ornstein–Uhlenbeck

Laura Rodrigues Vieira de Alencar, Marcio Martins, Gustavo Burin and Tiago Bosisio Quental. 2017. Arboreality Constrains Morphological Evolution but Not Species Diversification in Vipers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284(1869) DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2017.1775 | ||||||

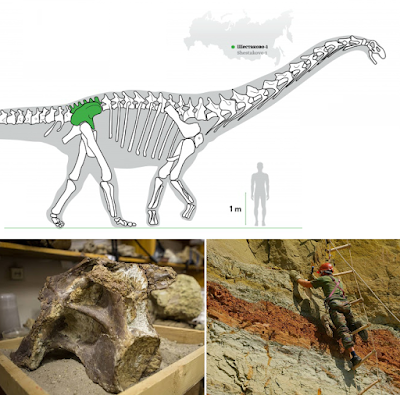

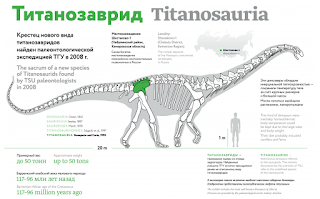

| 2:44p | [Paleontology • 2018] Sibirotitan astrosacralis • A New Sauropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Ilek Formation, Western Siberia, Russia

Abstract Sibirotitan astrosacralis nov. gen., nov. sp., is described based on isolated but possibly associated cervical and dorsal vertebrae, sacrum, and previously published pedal elements from the Lower Cretaceous (Barremian?) Ilek Formation at Shestakovo 1 locality (Kemerovo Province, Western Siberia, Russia). Some isolated sauropod teeth from the Shestakovo 1 locality are referred to the same taxon. The phylogenetic parsimony analyses place Sibirotitan astrosacralis nov. gen., nov. sp., as a non-titanosaurian somphospondyl titanosauriform. The new taxon exhibits four titanosauriform and one somphospondylan synapomorphies, and one autapomorphy – a hyposphene ridge that extends between the neural canal and the postzygapophyses. It differs from all other Somphospondyli by having only five sacral vertebrae. The new taxon shares with Euhelopus and Epachtosaurus sacral ribs that converge towards the middle of the sacrum in dorsal view. Sibirotitan astrosacralis nov. gen., nov. sp., is only the second sauropod taxon from Russia and one of the oldest titanosauriform described so far in Asia. Keywords: Sibirotitan astrosacralis nov. gen., nov. sp.; Titanosauriformes; Sauropoda; Phylogenetic parsimony analysis; Early Cretaceous; Siberia; Asia Dinosauria Owen, 1842 Saurischia Seeley, 1887 Sauropoda Marsh, 1878 Titanosauriformes Salgado et al., 1997 Genus Sibirotitan nov. gen. Derivation of the name: from Siberia and Greek Tιτάν (titan), a member of the second order of divine beings, descended from the primordial deities and preceding the Olympian deities in Greek mythology. Type and only species: Sibirotitan astrosacralis nov. gen., nov. sp. Derivation of the name: from Greek αστρον (star) and Latin os sacrum (“sacred bone”), an allusion to the unusual configuration of sacral ribs which radiate, in dorsal view, from the middle of the sacrum as the rays of a star.

Alexander Averianov, Stepan Ivantsov, Pavel Skutschas, Alexey Faingertz and Sergey Leshchinskiy. 2018. A New Sauropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Ilek Formation, Western Siberia, Russia. Geobios. In Press. DOI: 10.1016/j.geobios.2017.12.004 Averianov, A.O., Voronkevich, A.V., Maschenko, E.N., Leshchinskiy, S.V., and Fayngertz, A.V. 2002. A sauropod foot from the Early Cretaceous of Western Siberia, Russia. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 47 (1): 117–124. DOI: 10.1.1.492.1575 Hello to the Sibirosaurus? New dinosaur discovered by university scientists http://siberiantimes.com/science/casestu Познакомьтесь с новым сибирским динозавром https://metkere.com/2018/01/sibirotitan.h Новый род найденных в Кузбассе динозавров назвали сибиротитаном https://mediakuzbass.ru/news/obshhestvo/9 | ||||||

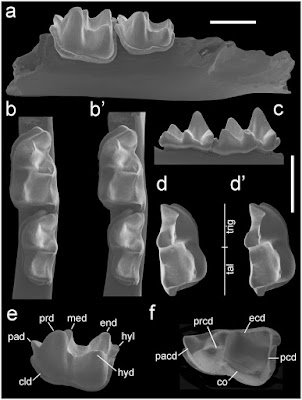

| 4:15p | [PaleoMammalogy • 2018] Vulcanops jennyworthyae • A New, Large-bodied Omnivorous Bat (Noctilionoidea: Mystacinidae) reveals Lost Morphological and Ecological Diversity since the Miocene in New Zealand

Abstract A new genus and species of fossil bat is described from New Zealand’s only pre-Pleistocene Cenozoic terrestrial fauna, the early Miocene St Bathans Fauna of Central Otago, South Island. Bayesian total evidence phylogenetic analysis places this new Southern Hemisphere taxon among the burrowing bats (mystacinids) of New Zealand and Australia, although its lower dentition also resembles Africa’s endemic sucker-footed bats (myzopodids). As the first new bat genus to be added to New Zealand’s fauna in more than 150 years, it provides new insight into the original diversity of chiropterans in Australasia. It also underscores the significant decline in morphological diversity that has taken place in the highly distinctive, semi-terrestrial bat family Mystacinidae since the Miocene. This bat was relatively large, with an estimated body mass of ~40 g, and its dentition suggests it had an omnivorous diet. Its striking dental autapomorphies, including development of a large hypocone, signal a shift of diet compared with other mystacinids, and may provide evidence of an adaptive radiation in feeding strategy in this group of noctilionoid bats. Systematic palaeontology Order Chiroptera Blumenbach, 1779 Suborder Yangochiroptera Van den Bussche & Hoofer, 2004 Superfamily Noctilionoidea Gray, 1821 Family Mystacinidae Dobson, 1875 Vulcanops jennyworthyae gen. et sp. nov. Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Lower Miocene of Central Otago, New Zealand. Etymology: From Vulcan, mythological god of fire and volcanoes (Roman), and ops, a suffix commonly used for bats; in reference to New Zealand’s tectonically active nature, as well as to the historic Vulcan Hotel, centre of the hamlet of St Bathans, from which the fauna takes its name. The species name honours Jennifer P. Worthy in recognition of her pivotal role in revealing the diversity of the St Bathans Fauna.

Suzanne J. Hand, Robin M. D. Beck, Michael Archer, Nancy B. Simmons, Gregg F. Gunnell, R. Paul Scofield, Alan J. D. Tennyson, Vanesa L. De Pietri, Steven W. Salisbury and Trevor H. Worthy. 2018. A New, Large-bodied Omnivorous Bat (Noctilionoidea: Mystacinidae) reveals Lost Morphological and Ecological Diversity since the Miocene in New Zealand. Scientific Reports. 8, Article number: 235. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-18403-w Giant extinct burrowing bat discovered in New Zealand phy.so/434803633 via @physorg_com | ||||||

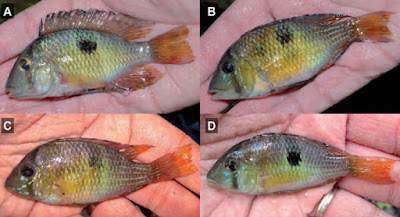

| 5:45p | [Ichthyology • 2017] Gymnogeophagus taroba • A New Species (Teleostei: Cichlidae) from the río Iguazú Basin, Misiones, Argentina

Abstract The Gymnogeophagus setequedas group is based on our results composed of three endemic species of which one, Gymnogeophagus taroba sp. n., is described as a new species. The three species are diagnosable from each other and from other species of Gymnogeophagus by stable differences in several morphological characters among which the best are found in coloration patterns. Body and head shapes and meristic characters show lesser differentiation but several are also clearly diagnostic in the G. setequedas group. The G. setequedas group is strongly structured allopatrically. The prime candidates for this fragmentation and speciation are the origins of the waterfalls on the individual tributaries. The largest of the waterfalls, the famous Cataratas del Iguazú, with a height of 72 m, separate G. taroba sp. n. from its closest relatives G. che and G. setequedas. The original 28 m high Urugua-í falls separate G. che from G. setequedas. Gymnogeophagus setequedas is separated from G. che and G. taroba by large rapids (about 65m in total elevation above the río Paraná) and a former fall on the Acaray river and by the 45 m high Monday falls located a few km from the mouth of the Monday into the río Paraná just opposite the mouth of the Iguazú. Key words. Cichlid fishes, endemism, morphology, La Plata River basin, Paraná river basin Taxonomy Family Cichlidae Bonaparte, 1835 Genus Gymnogeophagus Miranda Ribeiro, 1918 Gymnogeophagus taroba, new species (Figures 1-7; Table 1) Gymnogeophagus aff. setequedas Casciotta et al., 2016 (photo of live holotype, first mention of the species)Diagnosis. Gymnogeophagus taroba is distinguished from all species of Gymnogeophagus in the G. gymnogenys group by the possession of 23 to 25 E1 scales and the absence of a well developed adipose hump in adult males. Gymnogeophagus taroba is most easily distinguished from all species in the G. rhabdotus group (G. terrapurpura, G. rhabdotus, G. meridionalis, G. setequedas and G. che) by the pigmentation of the dorsal fin. .... ...... Etymology. The specific epithet taroba refers to Tarobá, a warrior, and refers to a legend of the Kaingang people; a noun in apposition. The Kaingang were the original first inhabitants of the present province of Misiones in Argentina and the southern Brazilian states of Paraná, Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul and also the southeastern state of São Paulo. Their language and culture is quite distinct from the neighboring Guaraní. The Kaingang language is classified as a member of the Gê language family. The legend tells that at the beginning of time, the río Iguazú was inhabited by a huge and monstrous serpent called Mboi, a guardian god. The Kaingang sacrificed a beautiful young maiden every year to Mboi. When Tarobá meets Naipí, chosen for the sacrifice, he rebells against the elders of the tribe who refuse to release her. Tarobá and Naipí try to escape in a canoe by the river. Mboi becomes furious and brakes the course of the river forming the Iguazú falls, catching the lovers. Naipí is transformed into one of the rocks of the falls, perpetually punished by the turbulent waters, and Tarobá is turned into a palm tree on the bank of the waterfall. Mboi lives submerged in the Garganta del Diablo, from where he watches over the lovers, preventing them from joining again. However, on sunny days and as a bridge of love, the rainbow overcomes the power of Mboi by rejoining Naipí and Tarobá. Jorge Casciotta, Adriana Almirón, Lubomir Piálek and Oldřich Říčan. 2017. Gymnogeophagus taroba (Teleostei: Cichlidae), A New Species from the río Iguazú Basin, Misiones, Argentina. HISTORIA NATURAL. Tercera Serie. 7(2); 5-22. Resumen. En base a nuestros resultados, el grupo Gymnogeophagus setequedas esta compuesto por tres especies endémicas, de las cuales, G. taroba sp. n., se describe como una nueva especie. Las tres especies son diagnosticables entre sí y de otras especies de Gymnogeophagus por diferencias estables en varios caracteres morfológicos, entre los cuales los mejores son los patrones de coloración. La forma del cuerpo, la cabeza y los caracteres merísticos muestran una menor diferenciación, pero algunos también son claramente diagnósticos en el grupo G. setequedas. El grupo G. setequedas está fuertemente estructurado alopátricamente. La causa principal para esta fragmentación y especiación es la formación de cascadas en los afluentes. La más grande de las cascadas, la famosa Catarata del Iguazú, con una altura de 72 m, separa G. taroba sp. n. de sus parientes más cercanos G. che y G. setequedas. El salto original del Urugua–í de 28 m de altura, separa G. che de G. setequedas. Gymnogeophagus setequedas está separada de G. che y G. taroba por grandes rápidos (unos 65 m de elevación total sobre el río Paraná) y un primer salto en el río Acaray y por otro salto de 45 m de altura en el río Monday localizado a unos pocos kilómetros de la desembocadura del Monday en el río Paraná justo enfrente de la desembocadura del Iguazú. Palabras clave. Cíclidos, endemismo, morfología, Cuenca del Plata, Cuenca del río Paraná |

| << Previous Day |

2018/01/13 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |