[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, May 9th, 2018

| Time | Event | ||||||||||

| 10:28a | [PaleoMammalogy • 2018] Evolutionary Adaptation to Aquatic Lifestyle in Extinct Sloths Thalassocnus Can Lead to Systemic Alteration of Bone Structure

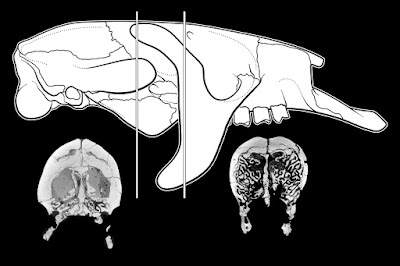

Abstract Through phenotypic plasticity, bones can change in structure and morphology, in response to physiological and biomechanical influences over the course of individual life. Changes in bones also occur in evolution as functional adaptations to the environment. In this study, we report on the evolution of bone mass increase (BMI) that occurred in the postcranium and skull of extinct aquatic sloths. Although non-pathological BMI in postcranial skeleton has been known in aquatic mammals, we here document general BMI in the skull for the first time. We present evidence of thickening of the nasal turbinates, nasal septum and cribriform plate, further thickening of the frontals, and infilling of sinus spaces by compact bone in the late and more aquatic species of the extinct sloth Thalassocnus. Systemic bone mass increase occurred among the successively more aquatic species of Thalassocnus, as an evolutionary adaptation to the lineage's changing environment. The newly documented pachyostotic turbinates appear to have conferred little or no functional advantage and are here hypothesized as a correlation with or consequence of the systemic BMI among Thalassocnus species. This could, in turn, be consistent with a genetic accommodation of a physiological adjustment to a change of environment. Keywords: bone mass increase, evolutionary adaptation, phenotypic plasticity, physiological adjustment, Thalassocnus, turbinates Conclusion: Systemic bone structure alteration, formerly known exclusively as a physiological adjustment, was here evidenced to have been retained as an evolutionary adaptation thanks to the outstandingly detailed (both in terms of geological age and anatomy) and early-stage record of a land-to-sea transition in the extinct sloth Thalassocnus. This new result is consistent with a macroevolutionary process of selection on environmentally induced variation of phenotypic plasticity [Gause, 1942; Sultan, 2017]. In other words, the systemic alteration of the highly plastic bone structure that gradually evolved among the species of Thalassocnus may represent an example of a macroevolutionary transition from a phenotypic accommodation (to an environmental change) to a genetic accommodation. In the context of the so-called extended (evolutionary) synthesis, Pigliucci [2010] points out the difficulty of uncovering such examples, which are required to corroborate the hypothesis that phenotypic plasticity has an important macroevolutionary role. The precise mechanism causing an adjustment (over the course of an individual's life) of bone structure in response to life in water is not understood. However, one can speculate that the shift of a terrestrial animal to an aquatic environment involves an increase in exercise intensity, which was shown to induce BMI [Lieberman, 1996; Biewener & Bertram, 1994]. There does not seem to be a clear influence of swimming on the bone mass of athletes [Gómez-Bruton, et al., 2013] (but differences in other physical activities probably prevent a direct correlation assessment in humans [Gómez-Bruton, et al., 2016]). However, rats that were swim-trained during growth have a greater overall bone mineral content and bone surface than the sedentary controls [McVeigh, et al., 2010] (but bone mineral density did not differ; and see [Bourrin, et al., 1992] for the opposite effect of endurance swim training on trabecular bone). It is noteworthy, however, that swim-trained animals do not necessarily experience a greater overall exercise intensity, as they were found to voluntarily run less outside the experimental exercise than control and running groups [McVeigh, et al., 2010]. Furthermore, bone structure at locations not directly influenced by locomotion, such as the cranial vault, does not seem to have been investigated in swim-trained animals. The lack of a similarly detailed fossil record in other ancestrally terrestrial tetrapods adapted to an aquatic lifestyle prevented drawing such a conclusion in their respective cases, but a similar process might have occurred during the evolutionary history of at least some of them. BMI is probably the most widespread lifestyle adaptation among aquatic tetrapods. This suggests that genetic accommodation of a trait subject to physiological adjustment such as bone structure alteration might have played an important role in great evolutionary transitions, of which the secondary adaptations of tetrapods to an aquatic lifestyle is an iconic example. Eli Amson, Guillaume Billet and Christian de Muizon. 2018. Evolutionary Adaptation to Aquatic Lifestyle in Extinct Sloths Can Lead to Systemic Alteration of Bone Structure. Proc. R. Soc. B. 285: 20180270. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2018.0270 The paper about the crazy pachyosteosclerosis in the skull of the marine sloth #Thalassocnus was published this morning in @RSocPublishing Proceedings B: doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.0270 …, to which I contributed my art. It was a pleasure to work with authors. #PaleoArt #SciArt | ||||||||||

| 1:28p | [Herpetology • 2018] Caecilia museugoeldi • A New Species of Caecilia Linnaeus, 1758 (Gymnophiona: Caeciliidae) from French Guiana

Abstract We describe a new species of the genus Caecilia from French Guiana. The new species differs from most species of the genus in the numbers of primary and secondary grooves. Color pattern, body shape, presence of subdermal scales, and number of teeth separate Caecilia museugoeldi sp. nov. from the other species of the genus. This new taxon is the first of the genus described in 33 years. Keywords: South America. Amazon. Taxonomy. Caecilian.

Caecilia museugoeldi sp. nov. .... Ecological observations In the same area where the specimen was collected, two other species of Gymnophiona were obtained as well, viz., Caecilia tentaculata and Rhinatrema bivittatum (Guerin-Menéville, 1838). All specimens were found crossing the road through rainforest at night. Etymology The name of the species is in honor of the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Belém, Pará, Brazil and is a noun in apposition. The Museu Goeldi is an institution which was established 151 years ago and is the oldest scientific institution in Brazilian Amazonia, which has steadily promoted studies of biodiversity, zoology, botany, archeology, geology, paleontology, hydrology, anthropology, ethnology, podology and linguistics of the area. Despite its important role in obtaining and dispersing knowledge about the biodiversity of the Amazonian basin in its broadest sense, the museum has recently been confronted with serious budgetary problems that should be solved for the long term in an acceptable way by the ministry that is responsible for the museum.

Adriano Oliveira Maciel and Marinus Steven Hoogmoed. 2018. A New Species of Caecilia Linnaeus, 1758 (Amphibia: Gymnophiona: Caeciliidae) from French Guiana [Uma nova espécie de Caecilia Linnaeus, 1758 (Amphibia: Gymnophiona: Caeciliidae) da Guiana Francesa]. Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi. Cienc. Nat., Belém. 13(1); 13-18. Nova espécie de "cobra-cega" na Guiana Francesa | Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi: museu-goeldi.br/portal/content/nova-esp-c Resumo: Descrevemos uma nova espécie do gênero Caecilia da Guiana Francesa. A nova espécie difere da maioria das espécies do gênero no número de sulcos primários e secundários. Padrão de cor, forma do corpo, presença de escamas subdermais e número de dentes separam Caecilia museugoeldi sp. nov. das outras espécies do gênero. Este novo táxon é o primeiro do gênero descrito em 33 anos. Palavras-chave: América do Sul. Amazônia. Taxonomia. Cecília | ||||||||||

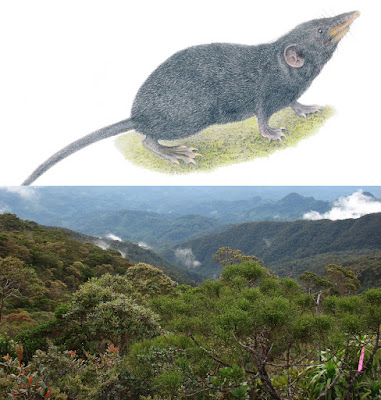

| 1:42p | [Mammalogy • 2018] Palawanosorex muscorum • A New Genus and Species of Shrew (Mammalia: Soricidae) from Palawan Island, Philippines

Abstract A 2007 survey of small mammals on Mt. Mantalingahan (2,086 m elevation), southern Palawan Island, Philippines, obtained specimens of a distinctive, previously unknown shrew (Soricidae). We describe these specimens as representing a new, monotypic genus and species, Palawanosorex muscorum. The new species was common on Mt. Mantalingahan from 1,550 to 1,950 m (near the peak) but was not detected from 700 to 1,300 m elevation. The previously known native, syntopic shrew, Crocidura palawanensis, has a slender body, slender fore and hind feet, and a long, thin tail with a few long bristles. In contrast, the new species has a stout body, broad fore feet, long claws, and a short tail covered by short, dense fur but no bristles. The dental formula traditionally used would result in assignment of the new species to Suncus, but several distinctive external and cranial features are present, and phylogenetic analyses of thousands of ultraconserved elements suggest P. muscorum is sister to most other Crocidurinae, a clade represented throughout Southeast Asia but numerically dominated by African species. The new species is a distant relative of Suncus murinus (the type species of Suncus) and all other known Southeast Asian species, including the only other shrew known to occur on Palawan (Crocidura batakorum). A time-calibrated phylogenetic analysis estimates divergence between Palawanosorex and its closest known relatives at approximately 10 Ma. Key words: endemism, Palawanosorex new genus, P. muscorum new species, Philippines, phylogeny, Soricidae, Southeast Asia, taxonomy, ultraconserved elements

Family Soricidae G. Fischer, 1814 Subfamily Crocidurinae Milne-Edwards, 1872 Palawanosorex, new genus Etymology.— Named for the island of Palawan in combination with Latin sorex, shrew. Gender of genus is masculine. Palawanosorex muscorum, new species Etymology.— The species name was derived from muscorum, genitive of Latin musci, mosses, meaning “of the mosses,” referring to the mossy habitat of the shrew. As an English vernacular name, we propose “Palawan Moss Shrew.”

Rainer Hutterer, Danilo S. Balete, Thomas C. Giarla, Lawrence R. Heaney and Jacob A. Esselstyn. 2018. A New Genus and Species of Shrew (Mammalia: Soricidae) from Palawan Island, Philippines. Journal of Mammalogy. gyy041 DOI: 10.1093/jmammal/gyy041 New shrew species discovered on 'sky island' in Philippines phys.org/news/2018-05-shrew-species-sky-i |

| << Previous Day |

2018/05/09 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |