[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Saturday, December 1st, 2018

| Time | Event | ||||||||

| 6:38a | [Botany • 2019] Acranthera hoangii (Rubiaceae) • A New Species from central Vietnam

ABSTRACT Acranthera hoangii Hareesh & T.A. Le (Rubiaceae) is described as a new species from Vietnam. The new species shows similarities with A. longipes, but shows significant differences in its densely pubescent shoot and petiole, larger flowers, five-nerved calyx lobes and ribbed ovary. KEYWORDS: Acranthera, Amphoterosanthus, new species, Rubiaceae, Vietnam

Acranthera hoangii Hareesh & T.A. Le, sp. nov. Etymology: The species is named in honour of Dr Hoang Le Tuan Anh, Director, Mientrung Institute for Scientific Research (MISR), Huynh Thuc Khang Street, Hue city who is the first to notice the plant during the collection in central Vietnam. Vadakkoot Sankaran Hareesh, Tuan Anh Le, Chinh Vu Tien and Cuong Pham Viet. 2019. Acranthera hoangii (Rubiaceae), A New Species from central Vietnam. Webbia: Journal of Plant Taxonomy and Geography. DOI: 10.1080/00837792.2018.1548813 | ||||||||

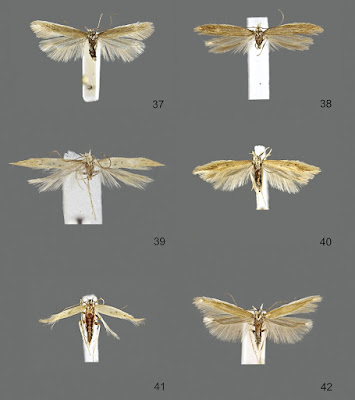

| 10:30a | [Entomology • 2018] Revision of the Genus Megacraspedus Zeller, 1839 (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae), A Challenging Taxonomic Tightrope of Species Delimitation

Abstract The taxonomy of the Palearctic genus Megacraspedus Zeller, 1839 (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae) is revised, based on external morphology, genitalia and DNA barcodes. An integrative taxonomic approach supports the existence of 85 species which are arranged in 24 species groups (disputed taxa from other faunal regions are discussed). Morphology of all species is described and figured in detail. For 35 species both sexes are described; for 46 species only the male sex is reported, in one species the male is unknown, whereas in three species the female adult and/or genitalia morphology could not be analysed due to lack of material. DNA barcode sequences of the COI barcode fragment with > 500 bp were obtained from 264 specimens representing 62 species or about three-quarters of the species. Species delimitation is particularly difficult in a few widely distributed species with high and allegedly intraspecific DNA barcode divergence of nearly 14%, and with up to 23 BINs in a single species. Deep intraspecific or geographical splits in DNA barcode are frequently not supported by morphology, thus indicating a complex phylogeographic history or other unresolved molecular problems. The following 44 new species (22 of them from Europe) are described: Megacraspedus bengtssoni sp. n. (Spain), M. junnilaineni sp. n. (Turkey), M. similellus sp. n. (Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey), M. golestanicus sp. n. (Iran), M. tokari sp. n. (Croatia), M. neli sp. n. (France, Italy), M. faunierensis sp. n. (Italy), M. gredosensis sp. n. (Spain), M. bidentatus sp. n. (Spain), M. fuscus sp. n. (Spain), M. trineae sp. n. (Portugal, Spain), M. skoui sp. n. (Spain), M. spinophallus sp. n. (Spain), M. occidentellus sp. n. (Portugal), M. granadensis sp. n. (Spain), M. heckfordi sp. n. (Spain), M. tenuiuncus sp. n. (France, Spain), M. devorator sp. n. (Bulgaria, Romania), M. brachypteris sp. n. (Albania, Greece, Macedonia, Montenegro), M. barcodiellus sp. n. (Macedonia), M. sumpichi sp. n. (Spain), M. tabelli sp. n. (Morocco), M. gallicus sp. n. (France, Spain), M. libycus sp. n. (Libya, Morocco), M. latiuncus sp. n. (Kazahkstan), M. kazakhstanicus sp. n. (Kazahkstan), M. knudlarseni sp. n. (Spain), M. tenuignathos sp. n. (Morocco), M. glaberipalpus sp. n. (Morocco), M. nupponeni sp. n. (Russia), M. pototskii sp. n. (Kyrgyzstan), M. feminensis sp. n. (Kazakhstan), M. kirgizicus sp. n. (Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan), M. ibericus sp. n. (Portugal, Spain), M. steineri sp. n. (Morocco), M. gibeauxi sp. n. (Algeria, Tunisia), M. multipunctellus sp. n. (Turkey), M. teriolensis sp. n. (Croatia, Greece, Italy, Slovenia), M. korabicus sp. n. (Macedonia), M. skulei sp. n. (Spain), M. longivalvellus sp. n. (Morocco), M. peslieri sp. n. (France, Spain), M. pacificus sp. n. (Afghanistan), and M. armatophallus sp. n. (Afghanistan). Nevadia Caradja, 1920, syn. n. (homonym), Cauloecista Dumont, 1928, syn. n., Reichardtiella Filipjev, 1931, syn. n., and Vadenia Caradja, 1933, syn. n. are treated as junior synonyms of Megacraspedus. Furthermore the following species are synonymised: M. subdolellus Staudinger, 1859, syn. n., M. tutti Walsingham, 1897, syn. n., and M. grossisquammellus Chrétien, 1925, syn. n. of M. lanceolellus (Zeller, 1850); M. culminicola Le Cerf, 1932, syn. n. of M. homochroa Le Cerf, 1932; M. separatellus (Fischer von Röslerstamm, 1843), syn. n. and M. incertellus Rebel, 1930, syn. n. of M. dolosellus (Zeller, 1839); M. mareotidellus Turati, 1924, syn. n. of M. numidellus (Chrétien, 1915); M. litovalvellus Junnilainen, 2010, syn. n. of M. imparellus (Fischer von Röslerstamm, 1843); M. kaszabianus Povolný, 1982, syn. n. of M. leuca (Filipjev, 1929); M. chretienella (Dumont, 1928), syn. n., M. halfella (Dumont, 1928), syn. n., and M. arnaldi (Turati & Krüger, 1936), syn. n. of M. violacellum (Chrétien, 1915); M. escalerellus Schmidt, 1941, syn. n. of M. squalida Meyrick, 1926. Megacraspedus ribbeella (Caradja, 1920), comb. n., M. numidellus (Chrétien, 1915), comb. n., M. albella (Amsel, 1935), comb. n., M. violacellum (Chrétien, 1915), comb. n., and M. grisea (Filipjev, 1931), comb. n. are newly combined in Megacraspedus. Keywords: Brachyptery, DNA barcoding, Gelechiidae, Lepidoptera, Megacraspedus, new species, Palearctic, taxonomy Peter Huemer and Ole Karsholt. 2018. Revision of the Genus Megacraspedus Zeller, 1839, A Challenging Taxonomic Tightrope of Species Delimitation (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae). ZooKeys. 800: 1-278. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.800.26292 | ||||||||

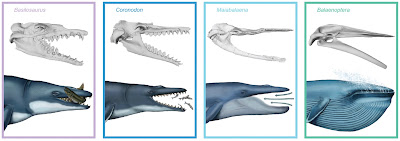

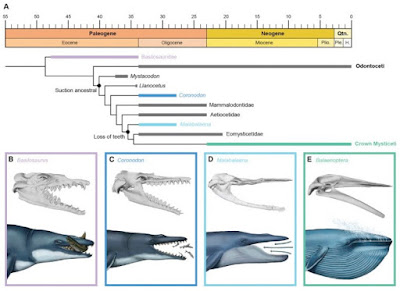

| 1:55p | [PaleoMammalogy • 2018] Maiabalaena nesbittae • Tooth Loss Precedes the Origin of Baleen in Whales

Highlights • Maiabalaena nesbittae is 33 million year old fossil baleen whale from Oregon • Maiabalaena has neither teeth, nor baleen • Early whales lost teeth entirely before the evolutionary origin of baleen • Despite no teeth or baleen, these whales were effective suction feeders Summary Whales use baleen, a novel integumentary structure, to filter feed; filter feeding itself evolved at least five times in tetrapod history but demonstrably only once in mammals. Living baleen whales (mysticetes) are born without teeth, but paleontological and embryological evidence demonstrate that they evolved from toothed ancestors that lacked baleen entirely. The mechanisms driving the origin of filter feeding in tetrapods remain obscure. Here we report Maiabalaena nesbittae gen. et sp. nov., a new fossil whale from early Oligocene rocks of Washington State, USA, lacking evidence of both teeth and baleen. The holotype possesses a nearly complete skull with ear bones, both mandibles, and associated postcrania. Phylogenetic analysis shows Maiabalaena as crownward of all toothed mysticetes, demonstrating that tooth loss preceded the evolution of baleen. The functional transition from teeth to baleen in mysticetes has remained enigmatic because baleen decays rapidly and leaves osteological correlates with unclear homology; the oldest direct evidence for fossil baleen is ∼25 million years younger than the oldest stem mysticetes (∼36 Ma). Previous hypotheses for the origin of baleen are inconsistent with the morphology and phylogenetic position of Maiabalaena. The absence of both teeth and baleen in Maiabalaena is consistent with recent evidence that the evolutionary loss of teeth and origin of baleen are decoupled evolutionary transformations, each with a separate morphological and genetic basis. Understanding these macroevolutionary patterns in baleen whales is akin to other macroevolutionary transformations in tetrapods such as scales to feathers in birds. Keywords: baleen, cetacea, filter-feeding, mysticeti, suction feeding

Systematics Cetacea; Pelagiceti; Neoceti; Mysticeti; Maiabalaena nesbittae gen. et sp. nov. Etymology: Maiabalaena combines Maia-, meaning mother, and -balaena, meaning whale. Named for its phylogenetic position as basal to baleen-bearing mysticetes. The specific epithet nesbittae honors Dr. Elizabeth A. Nesbitt for her lifetime of contribution to paleontology of the Pacific Northwest and her mentorship and collegiality at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle, Washington, USA.

Carlos Mauricio Peredo, Nicholas D. Pyenson, Christopher D. Marshall and Mark D. Uhen. 2018. Tooth Loss Precedes the Origin of Baleen in Whales. Current Biology. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.10.047 Whales Lost Their Teeth Before Evolving Hair-like Baleen in Their Mouths si.edu/newsdesk/releases/whales-lost-the Toothless, 33-Million-Year-Old Whale Could Be an Evolutionary ‘Missing Link’ gizmodo.com/toothless-33-million-year-ol | ||||||||

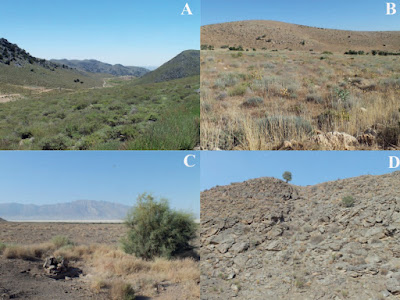

| 3:01p | [Herpetology • 2018] Macrovipera razii • Molecular and Morphological Analyses have revealed A New Species of Blunt-nosed Viper of the Genus Macrovipera in Iran

Abstract A new species of blunt-nosed viper of the genus Macrovipera is described from the central and southern parts of Iran on the basis of morphological and molecular examination. The mitochondrial Cytb gene was used to investigate phylogenetic relationships amongst the Iranian species of the genus Macrovipera. A dataset with a final sequence length of 1043 nucleotides from 41 specimens from 18 geographically distant localities across Iran was generated. The findings demonstrated that two major clades with strong support can be identified within the genus Macrovipera in Iran. One clade consists of individuals belonging to a new species, which is distributed in the central and southern parts of Iran; the second clade includes two discernible subclades. The first subclade is distributed in western and northwestern Iran, Macrovipera lebetina obtusa, and the second subclade consists of northeastern populations, representing Macrovipera lebetina cernovi. The new species, Macrovipera razii sp. n., differs from its congeners by having higher numbers of ventral scales, elongated anterior chin-shields, and lower numbers of canthal plus intersupraocular scales. Key words. Squamata, Serpentes, Viperidae, Macrovipera, new species, mitochondrial Cytb, phylogeny, taxonomy, Iran.

Macrovipera razii sp. n. Differential diagnosis: The newly described species differs from M. schweizeri by its higher number of mid-dorsal scales (25 vs. 23), which however overlaps the counts in other M. lebetina subspecies. Macrovipera razii sp. n. differs from M. lebetina by possessing a higher count of ventrals (172–175 vs. 160–170), and by having elongated anterior chin-shields, which are more than three times longer than the posterior ones. In contrast, M. lebetina has square anterior chin-shields, which are less than twice as long as the posterior chin-shields (Fig. 6). Compared to M. lebetina, the new species has a lower number of canthal + intersupraocular scales. More comparisons are provided in Table 4. Interestingly, Macrovipera razii sp. n. and M. lebetina cernovi are similar in both possessing one large supraocular scale, which is absent in M. lebetina obtusa (Fig. 5). Outside Iran, the subspecies M. lebetina euphratica (Schmidt, 1939) differs by having supraoculars that are split up into five scales, making it clearly distinguishable from Macrovipera razii sp. n., which has one large supraocular scale. The latter can be distinguished from Macrovipera lebetina lebetina (Linnaeus, 1758) and Macrovipera lebetina transmediterranea (Nilson & Andrén 1988) by the higher number of ventrals (172– 175 vs. 146–163 and 150–164, respectively), from Macrovipera lebetina turanica (Chernov, 1940) by the latter’s semidivided supraoculars and a dorsal colour pattern that consists of a dark ground colour with a lighter, orange zigzag pattern. .... Etymology: The specific epithet is a noun in the genitive case, in honour of Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyya al-Razi (854–925 CE), a Persian polymath, physician, alchemist, philosopher, and important figure in the history of medicine. Macrovipera is one of the most medically important snakes in Iran, and historically, physicians like him have been involved in snake bite therapy. We propose “Razi’s Viper” as a standard English name. Distribution: All our specimens of Macrovipera razii sp. n. were collected from localities in central and southern Iran (Table 1, Fig. 1). This species might occur in other provinces of Iran, too, however. It is at present considered to be endemic to Iran. Hamzeh Oraie, Eskandar Rastegar-Pouyani, Azar Khosravani, Naeim Moradi, Abolfazl Akbari, Mohammad Ebrahim Sehhatisabet, Soheila Shafiei, Nikolaus Stümpel and Ulrich Joger. 2018. Molecular and Morphological Analyses have revealed A New Species of Blunt-nosed Viper of the Genus Macrovipera in Iran. SALAMANDRA. 54(4); 233-248. |

| << Previous Day |

2018/12/01 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |