[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, January 30th, 2020

| Time | Event | ||

| 4:30a | [Herpetology • 2020] Gonatodes chucuri • A New Species of the Genus Gonatodes (Squamata: Sauria: Sphaerodactylidae) from the western flank of the Cordillera Oriental in Colombia

Abstract We describe a new sphaerodactylid lizard of the genus Gonatodes from the western flank of the Cordillera Oriental, Santander Department, Colombia based on morphological and molecular data. The new species is distinguished from all congeners by having a medium body size, by the absence of both a supraciliary spine and of clusters of distinctly enlarged conical scales on the sides and by having a subcaudal scale pattern (1’1”) and a cryptic dorsal color pattern in both sexes. Additionally, we describe for the first time the hemipenial morphology for a species of the genus. The new species increases the number of Gonatodes known from Colombia to eight and is the only known species of the country, as well as the second known mainland species of the genus not exhibiting sexual dichromatism. Keywords: Reptilia, Molecular phylogenetics, morphology, hemipenial, taxonomy, sexual dichromatism Gonatodes chucuri Elson Meneses-Pelayo and Juan P. Ramírez. 2020. A New Species of the Genus Gonatodes (Squamata: Sauria: Sphaerodactylidae) from the western flank of the Cordillera Oriental in Colombia, with Description of Its Hemipenial Morphology. Zootaxa. 4729(2); 207–227. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4729.2.4 | ||

| 9:24a | [Botany • 2020] Genlisea hawkingii (Lentibulariaceae) • A New Species from Serra da Canastra, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Abstract Genlisea hawkingii, which is a new species of Genlisea subgen. Tayloria (Lentibulariaceae) from cerrado in southwest Brazil, is described and illustrated. This species has been found in only one locality thus far, in the Serra da Canastra, which is located in the Delfinópolis municipality in Minas Gerais, Brazil. The new species is morphologically similar to Genlisea violacea and G. flexuosa, but differs from them in having a corolla with a conical and curved spur along with sepals with an acute apex and reproductive organs that only have glandular hairs. Moreover, it is similar to G. uncinata’s curved spur. G. hawkingii is nested within the subgen. Tayloria clade as a sister group to all the other species of this subgenus. Therefore, both morphological and phylogenetic results strongly support G. hawkingii as a new species in the subgen. Tayloria. Genlisea hawkingii S.R.Silva, B.J.Płachno & V.Miranda, sp. nov. Diagnosis: Similar to Genlisea violacea A.St.-Hil. and G. flexuosa Rivadavia, A.Fleischm. & Gonella, but it is distinct for the dark green leaves having a glabrous lamina and the flower that has a long conical spur with a curved apex, acute sepals apex and reproductive organs that are exclusively covered with glandular hairs. Etymology: The species epithet ‘hawkingii’ was attributed as homage to the great English theoretical physicist and cosmologist, Stephen William Hawking, who died on March 14, 2018. We were impressed with his life’s trajectory and his outstanding discoveries in cosmology. He became a signpost not only for other scientists but for all people. Saura Rodrigues Silva, Bartosz Jan Płachno, Samanta Gabriela Medeiros Carvalho and Vitor Fernandes Oliveira Miranda. 2020. Genlisea hawkingii (Lentibulariaceae), A New Species from Serra da Canastra, Minas Gerais, Brazil. PLoS ONE. 15(1): e0226337. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226337 | ||

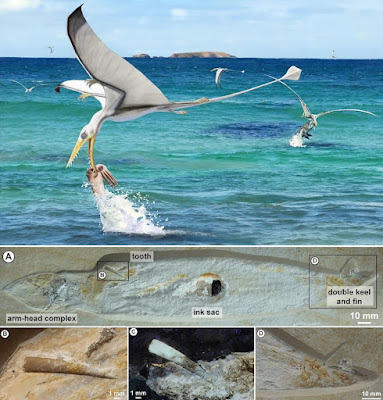

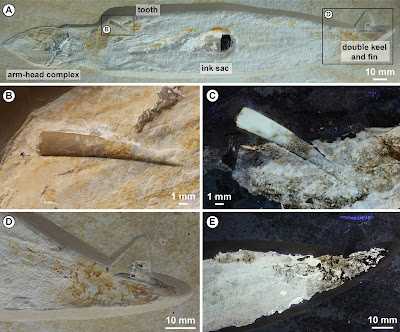

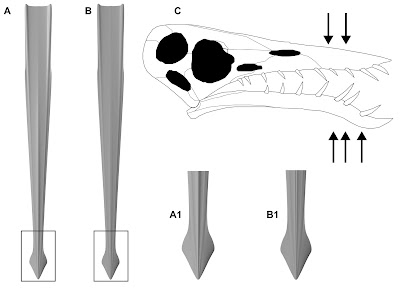

| 9:47a | [Paleontology • 2020] Pterosaurs ate Soft-bodied Cephalopods (Coleoidea) Abstract Direct evidence of successful or failed predation is rare in the fossil record but essential for reconstructing extinct food webs. Here, we report the first evidence of a failed predation attempt by a pterosaur on a soft-bodied coleoid cephalopod. A perfectly preserved, fully grown soft-tissue specimen of the octobrachian coleoid Plesioteuthis subovata is associated with a tooth of the pterosaur Rhamphorhynchus muensteri from the Late Jurassic Solnhofen Archipelago. Examination under ultraviolet light reveals the pterosaur tooth is embedded in the now phosphatised cephalopod soft tissue, which makes a chance association highly improbable. According to its morphology, the tooth likely originates from the anterior to middle region of the upper or lower jaw of a large, osteologically mature individual. We propose the tooth became associated with the coleoid when the pterosaur attacked Plesioteuthis at or near the water surface. Thus, Rhamphorhynchus apparently fed on aquatic animals by grabbing prey whilst flying directly above, or floating upon (less likely), the water surface. It remains unclear whether the Plesioteuthis died from the pterosaur attack or survived for some time with the broken tooth lodged in its mantle. Sinking into oxygen depleted waters explains the exceptional soft tissue preservation. Conclusion: We describe an adult specimen of the extremely rare octobrachian coleoid cephalopod Plesioteuthis subovata preserved with a tooth of the pterosaur Rhamphorhynchus muensteri in its mantle tissue. We present this association as the first direct evidence of a predator-prey interaction between pterosaurs and cephalopods. This interaction took place at or near the water surface. A scavenging feeding mode for Rhamphorhynchus is doubtful because the pterosaur is unlikely to have dived to the highly dangerous anoxic sediment floor to access carrion. It is also unlikely that tooth breakage would occur while consuming the soft decaying mantle of a coleoid carcass. Most likely, the tooth broke off in the Plesioteuthis mantle when the pterosaur attacked and the cephalopod tried to escape. High mechanical stress was exerted to the base of the teeth that were in direct contact with the cephalopod. This fractured at least one tooth, which remained stuck in the mantle. It is impossible to assess whether the Plesioteuthis died as a result of the pterosaur attack or survived with the broken tooth in its mantle. In addition to revealing cephalopods as a likely part of the Rhamphorhynchus diet, this fossil provides evidence that Plesioteuthis commonly lived in the upper part of the water column where it was accessible to pterosaurs. R. Hoffmann, J. Bestwick, G. Berndt, R. Berndt, D. Fuchs and C. Klug. 2020. Pterosaurs ate Soft-bodied Cephalopods (Coleoidea). Scientific Reports. 10, 1230. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-57731-2 | ||

| 10:50a | [Mammalogy • 2020] Colombian Hippo Population: Ecosystem Effects of the World’s Largest Invasive Animal

Abstract The keystone roles of mega‐fauna in many terrestrial ecosystems have been lost to defaunation. Large predators and herbivores often play keystone roles in their native ranges, and some have established invasive populations in new biogeographic regions. However, few empirical examples are available to guide expectations about how mega‐fauna affect ecosystems in novel environmental and evolutionary contexts. We examined the impacts on aquatic ecosystems of an emerging population of hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibus) that has been growing in Colombia over the last 25 years. Hippos in Africa fertilize lakes and rivers by grazing on land and excreting wastes in the water. Stable isotopes indicate that terrestrial sources contribute more carbon in Colombian lakes containing hippo populations, and daily dissolved oxygen cycles suggest that their presence stimulates ecosystem metabolism. Phytoplankton communities were more dominated by cyanobacteria in lakes with hippos, while bacteria, zooplankton and benthic invertebrate communities were similar regardless of hippo presence. Our results suggest that hippos recapitulate their role as ecosystem engineers in Colombia, importing terrestrial organic matter and nutrients with detectable impacts on ecosystem metabolism and community structure in the early stages of invasion. Ongoing range expansion may pose a threat to water resources. Keywords: hippopotamus, lakes, productivity, water resources, exotic species, eutrophication Jonathan B. Shurin, Nelson Aranguren Riaño, Daniel Duque Negro, David Echeverri Lopez, Natalie T. Jones, Oscar Laverde‐R, Alexander Neu and Adriana Pedroza Ramos. 2020. Ecosystem Effects of the World’s Largest Invasive Animal. Ecology. DOI: 10.1002/ecy.2991 UC San Diego scientists and their colleagues have published the first scientific assessment of the impact that an invasive hippo population, imported by infamous drug lord Pablo Escobar, is having on Colombian aquatic ecosystems. The study revealed that the hippos are changing the area's water quality by importing large amounts of nutrients and organic material from the surrounding landscape. A Drug Lord and the World’s Largest Invasive Animal ucsdnews.UCSD.edu/feature/a-drug-lord-and-the-worlds-l |

| << Previous Day |

2020/01/30 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |