[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, March 27th, 2020

| Time | Event | ||||||

| 12:18a | [Herpetology • 2020] A Taxonomic Revision of the South-eastern Dragon Lizards of the Smaug warreni (Boulenger) Species Complex (Squamata: Cordylidae) in southern Africa, with the Description of A New Species, Smaug swazicus

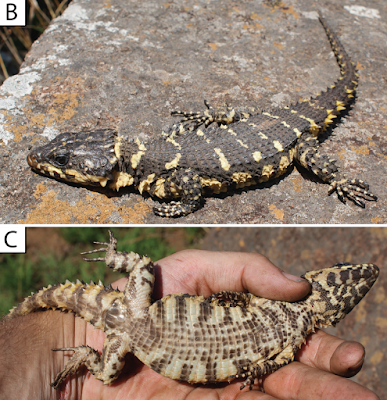

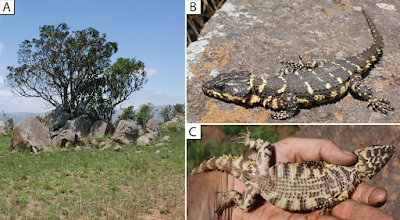

Abstract A recent multilocus molecular phylogeny of the large dragon lizards of the genus Smaug Stanley et al. (2011) recovered a south-eastern clade of two relatively lightly-armoured, geographically-proximate species (Smaug warreni (Boulenger, 1908) and S. barbertonensis (Van Dam, 1921)). Unexpectedly, S. barbertonensis was found to be paraphyletic, with individuals sampled from northern Eswatini (formerly Swaziland) being more closely related to S. warreni than to S. barbertonensis from the type locality of Barberton in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Examination of voucher specimens used for the molecular analysis, as well as most other available museum material of the three lineages, indicated that the ‘Eswatini’ lineage—including populations in a small area on the northern Eswatini–Mpumalanga border, and northern KwaZulu–Natal Province in South Africa—was readily distinguishable from S. barbertonensis sensu stricto (and S. warreni) by its unique dorsal, lateral and ventral colour patterns. In order to further assess the taxonomic status of the three populations, a detailed morphological analysis was conducted. Multivariate analyses of scale counts and body dimensions indicated that the ‘Eswatini’ lineage and S. warreni were most similar. In particular, S. barbertonensis differed from the other two lineages by its generally lower numbers of transverse rows of dorsal scales, and a relatively wider head. High resolution Computed Tomography also revealed differences in cranial osteology between specimens from the three lineages. The ‘Eswatini’ lineage is described here as a new species, Smaug swazicus sp. nov., representing the ninth known species of dragon lizard. The new species appears to be near-endemic to Eswatini, with about 90% of its range located there. Our study indicates that S. barbertonensis sensu stricto is therefore a South African endemic restricted to an altitudinal band of about 300 m in the Barberton–Nelspruit–Khandizwe area of eastern Mpumalanga Province, while S. warreni is endemic to the narrow Lebombo Mountain range of South Africa, Eswatini and Mozambique. We present a detailed distribution map for the three species, and a revised diagnostic key to the genus Smaug.

Systematics Family Cordylidae Gray, 1838Smaug swazicus Bates & Stanley sp. nov. Swazi Dragon Lizard Diagnosis. (includes ‘additional material’) Distinguished from all other cordylids (Cordylidae) by its unique combination of dorsal, lateral and ventral colour patterns (see descriptions and figures). Referable to the genus Smaug on the basis of its large size and robust body, enlarged and spinose dorsal and caudal scales, enlarged occipital scales, and frontonasal in contact with the rostral, separating the nasal scales. A medium to large species of Smaug distinguishable by the following combination of characters: (1) back dark brown usually with 5–6 pale bands (usually interrupted) between fore- and hindlimbs, each band consisting of pale, sometimes dark-edged, markings; (2) pale band on nape behind occipitals; (3) flanks with large pale spots or blotches; (4) belly pale with a dark median longitudinal band bordered on either side by broad, dark, bands; (5) throat pale with extensive bold brown mottling (sometimes forming transverse bands; often much of throat is dark); (6) six enlarged, moderately to non-spinose, occipital scales, middle pair the smallest, outer occipitals usually shorter than the adjacent inner ones; (7) dorsolateral and lateral scales moderately spinose; (8) tail moderately spikey; (9) dorsal scale rows transversely 31–41; (10) dorsal scale rows longitudinally 20–26; (11) ventral scale rows transversely 23–29; (12) ventral scale rows longitudinally 14 (rarely 12); (13) femoral pores per thigh 10–13; subdigital lamellae on 4th toe 16–19. ....

Etymology. Named for the Kingdom of Eswatini, the country where most of the species’ range is located. Both ‘eSwatini’ and ‘Swaziland’ derive from the word iSwazi, after the name of an early chief, Mswati II (c. 1820–1868). Distribution. Highveld and Middleveld of Eswatini in Hhohho, Manzini and Shiselweni Regions, and adjacent areas in the South African provinces of (eastern) Mpumalanga (in Nkomazi municipality) and (northern) KwaZulu–Natal (in uPhongolo and Abaqulusi municipalies) (Fig. 9) at elevations of 462 to 1,139 m a.s.l.    Natural history. Diurnal and rupicolous, living in deep, horizontal (or gently sloping) crevices in granitic rock along hillsides, usually in the partial shade of trees (Fig. 8A; see also Jacobsen, 1989). According to R.C. Boycott (in litt., 2019), rocky terrain in closed canopy bushveld is the preferred habitat in Eswatini. A specimen in Ithala Game Reserve in KwaZulu–Natal was photographed on a tree trunk (ReptileMAP, VM no. 152451). When grasped by the hind limb, an individual from the type series performed an unusual anti-predator behaviour by repeatedly flexing and extending the inhibited limb caudally, so as to pull the captors’ digits directly onto the very sharp whorl of spines at the base of the tail (E.L. Stanley, 2008, personal observation). Michael F. Bates and Edward L. Stanley. 2020. A Taxonomic Revision of the South-eastern Dragon Lizards of the Smaug warreni (Boulenger) Species Complex in southern Africa, with the Description of A New Species (Squamata: Cordylidae). PeerJ. 8:e8526. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.8526 Here be dragons: Analysis reveals new species in Smaug lizard group FloridaMuseum.ufl.edu/science/smaug-swaz sciencecover.com/3619-2-here-be-dragons-a | ||||||

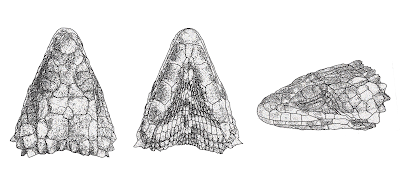

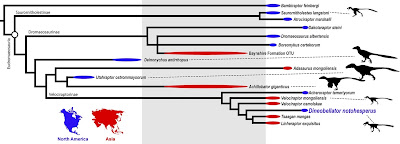

| 2:59a | [Paleontology • 2020] Dineobellator notohesperus • New Dromaeosaurid Dinosaur (Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae) from New Mexico and Biodiversity of Dromaeosaurids at the End of the Cretaceous

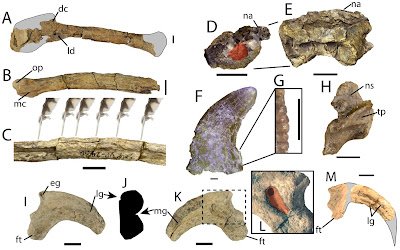

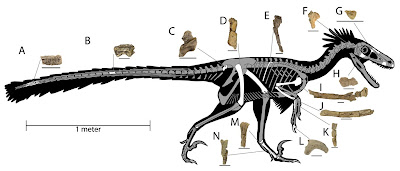

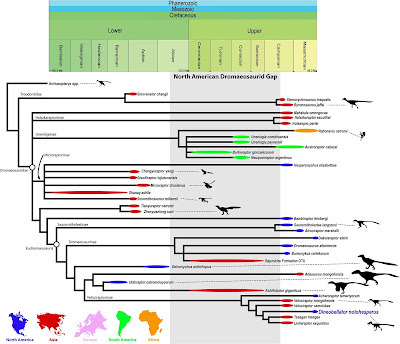

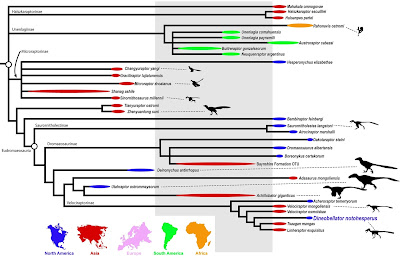

Abstract Dromaeosaurids (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae), a group of dynamic, swift predators, have a sparse fossil record, particularly at the time of their extinction near the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. Here we report on a new dromaeosaurid, Dineobellator notohesperus, gen. and sp. nov., consisting of a partial skeleton from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of New Mexico, the first diagnostic dromaeosaurid to be recovered from the latest Cretaceous of the southern United States (southern Laramidia). The holotype includes elements of the skull, axial, and appendicular skeleton. The specimen reveals a host of morphologies that shed light on new behavioral attributes for these feathered dinosaurs. Unique features on its forelimbs suggest greater strength capabilities in flexion than the normal dromaeosaurid condition, in conjunction with a relatively tighter grip strength in the manual claws. Aspects of the caudal vertebrae suggest greater movement near the tail base, aiding in agility and predation. Phylogenetic analysis places Dineobellator within Velociraptorinae. Its phylogenetic position, along with that of other Maastrichtian taxa (Acheroraptor and Dakotaraptor), suggests dromaeosaurids were still diversifying at the end of the Cretaceous. Furthermore, its recovery as a second North American Maastrichtian velociraptorine suggests vicariance of North American velociraptorines after a dispersal event during the Campanian-Maastrichtian from Asia. Features of Dineobellator also imply that dromaeosaurids were active predators that occupied discrete ecological niches while living in the shadow of Tyrannosaurus rex, until the end of the dinosaurs’ reign. Systematic paleontology Dinosauria Owen, 1842; Theropoda Marsh, 1881; Coelurosauria Huene, 1914; Dromaeosauridae Matthew and Brown, 1922; Dineobellator notohesperus gen. et sp. nov. Etymology: The generic name is derived from Diné, the Navajo word in reference to the people of the Navajo Nation, and the Latin suffix bellator, meaning warrior. The specific epithet noto is from the Greek, meaning southern, or south; and the Greek hesper meaning western, in reference to the American Southwest. Additionally, Hesperus refers to a Greek god, namely the personification of the evening star and, by extension, “western.” Pronounced “dih NAY oh - BELL a tor” “Noh toh – hes per us.” Holotype: SMP VP-2430 is a disarticulated, associated individual consisting of a rostromedial portion of right premaxilla, left maxilla fragment, ?maxillary tooth, dorsolateral process of left lacrimal, left ?nasal fragment, incomplete right jugal, incomplete right basipterygoid, incomplete occipital condyle, isolated prezygopophyses, isolated vertebral processes, caudal vertebra 1, middle caudal vertebra, four fused distal caudal vertebrae, several vertebral fragments, nearly complete rib and rib fragments, nearly complete right humerus, nearly complete right ulna, incomplete right metacarpal III, nearly complete right manual ungual II, incomplete right femur, incomplete right metatarsals I, II and III, incomplete left ?astragalus, nearly complete right pedal ungual III, and various other cranial and post-cranial bone fragments (Figs. 1–2). Portions of the specimen were first found and collected by Robert M. Sullivan, Steven E. Jasinski, and James Nikas in 2008, and more material was subsequently collected from the same individual by Sullivan and Jasinski in 2009 and Jasinski in 2015 and 2016. Type locality and horizon: The type locality, SMP 410b, Bisti/De-na-zin Wilderness, New Mexico. Precise locality information is on file at the State Museum of Pennsylvania, Section of Paleontology and Geology, and is available to qualified researchers. The holotype (SMP VP-2430) was collected within a few meters above the base of the Naashoibito Member (Ojo Alamo Formation) in relatively poorly consolidated sandstone. 40Ar/39Ar dates acquired from detrital sanidines give a maximum depositional age for the Naashoibito Member at 66.5 ± 0.2 Ma (upper Maastrichtian)16,17,18,19,20. Biostratigraphy, however, seems to suggest an early late Maastrichtian age, approximately 70.0–68.0 Ma21. Diagnosis: A mid-sized dromaeosaurid theropod that differs from other eudromaeosaurs by the following characters: offset of lateral grooves on manual ungual; distinct and conspicuous dorsomedial groove proximally dorsal to the articular surface on the manual ungual; sharp angle of distal deltopectoral crest of the humerus; opisthocoelous proximal caudal vertebrae; short and robust neural spines on proximal caudal vertebrae; gracile and subrectangular transverse processes on proximal caudal vertebrae; proximal caudal vertebrae with curved ventral surface and oval to subrectangular cranial and caudal centrum surfaces; distinct round concavities on cranial and caudal centrum surfaces in mid-caudal vertebrae; enlarged flexor tubercles on manual ungual II and pedal ungual III; and secondary lateral grooves ventral on pedal unguals. Steven E. Jasinski, Robert M. Sullivan and Peter Dodson. 2020. New Dromaeosaurid Dinosaur (Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae) from New Mexico and Biodiversity of Dromaeosaurids at the End of the Cretaceous. Scientific Reports. 10: 5105. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-61480-7 Scientists working in New Mexico found a fossilized 6-inch dinosaur claw that has led them to recognize a fierce new species, Dineobellator notohesperus |

| << Previous Day |

2020/03/27 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |