[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, May 14th, 2020

| Time | Event | ||||

| 12:43a | [Herpetology • 2020] What’s Under the Hood? Phylogeny and Taxonomy of the Snake Genera Parasuta and Suta (Squamata: Elapidae), with A Description of A New Species from the Pilbara, Western Australia

Abstract Despite decades of phylogenetic studies, the generic and species-level relationships of some Australian elapid snakes remain problematic. The morphologically conservative genus Parasuta comprises small nocturnal snakes with a particularly obfuscated taxonomic history. Here we provide a molecular phylogenetic analysis of all currently recognised species including members of the sister genus Suta and provide new morphological data that lead to a taxonomic revision of generic and species boundaries. We failed to find support for monophyly of Parasuta or Suta, instead supporting previous evidence that these two genera should be combined. Our species-level investigations revise the boundaries between P. gouldii (Gray) and P. spectabilis (Krefft) resulting in recognition that both P. spectabilis bushi (Storr) and P. spectabilis nullarbor (Storr) are conspecific with P. gouldii. We also find the Pilbara population of P. monachus (Storr) to be specifically distinct. As a consequence of this information, we synonymise Parasuta with its senior synonym Suta, redescribe S. gouldii, S. monachus and S. spectabilis to clarify morphological and geographical boundaries and describe Suta gaikhorstorum sp. nov., which differs from all other described Suta species, including the geographically proximate and similar-looking S. monachus, by a combination of molecular genetic markers, morphometric attributes, details of colouration and scalation. The recognition of S. gaikhorstorum sp. nov. adds to the growing list of the many endemic reptiles from this exceptionally diverse biotic region. We also designate a lectotype for S. spectabilis from the original syntype series, highlight a distinctive population from the Great Victoria Desert in Western Australia and comment on further unresolved issues regarding the relationships between S. dwyeri (Worrell) and S. nigriceps (Gȕnther). Keywords: Reptilia, morphology, synonymy, Great Victoria Desert, Nullarbor Plain, Suta gaikhorstorum sp. nov., Suta gouldii, Suta monachus, Suta spectabilis Taxonomy Elapidae Suta Worrell, 1961 Type species. Hoplocephalus sutus (= Suta suta) Peters 1863: 234, by original tautonymy. Synonymy this study. Parasuta Worrell 1961: 26. Type species. Elaps gouldii (= Suta gouldii) Gray 1841: 91. Suta gouldii (Gray, 1841) Gould’s Hooded Snake Suta spectabilis (Krefft, 1869) Lesser Hooded Snake Suta monachus (Storr, 1964) Inland Hooded Snake

Suta gaikhorstorum sp. nov. Pilbara Hooded Snake Etymology. We take pleasure in naming this species after passionate naturalists, wildlife educators and rehabilitators Klaas & Mieke Gaikhorst of the Armadale Reptile & Wildlife Centre, who have made an immense contribution to the public awareness of Australia’s natural heritage. Brad Maryan, Ian G. Brennan, Mark N. Hutchinson and Lukas S. Geidans. 2020. What’s Under the Hood? Phylogeny and Taxonomy of the Snake Genera Parasuta Worrell and Suta Worrell (Squamata: Elapidae), with A Description of A New Species from the Pilbara, Western Australia. Zootaxa. 4778(1); 1–47. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4778.1.1 | ||||

| 1:34a | [Botany • 2020] Revision of Angraecum sect. Perrierangraecum (Orchidaceae; Epidendroideae; Vandeae) for the Mascarenes, with A Description of A New Endemic Species for Mauritius

Abstract While revising the genus Angraecum (Orchidaceae) for the Mascarenes, a new taxon endemic to Mauritius was identified and it is here described as Angraecum baiderae. More than 300 Angraecum specimens, including types, collected in the Mascarenes and Madagascar, and available at DBEV, G, K, KM, L, MARS, MAU, MO, P, REU, SEY, TEF, and TAN were studied to confirm the taxonomic status of this new taxon. Its conservation status was assessed as Endangered. Furthermore, this paper presents detailed descriptions, conservation status, and a key to all species of Angraecum sect. Perrierangraecum occurring in the Mascarenes. Keywords: conservation, IUCN Red List, Mauritius, orchid, Réunion, taxonomy, Monocots Thierry Pailler, Simon Verlynde, Benny Bytebier, F.B. Vincent Florens and Claudia Baider. 2020. Revision of Angraecum sect. Perrierangraecum (Orchidaceae; Epidendroideae; Vandeae) for the Mascarenes, with A Description of A New Endemic Species for Mauritius. Phytotaxa. 442(3); 183–195. DOI: 10.11646/phytotaxa.442.3.4 | ||||

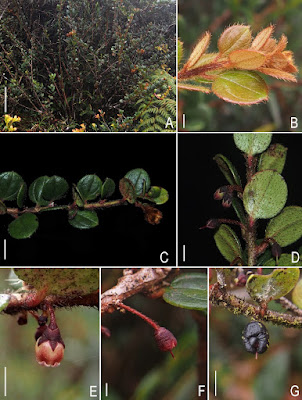

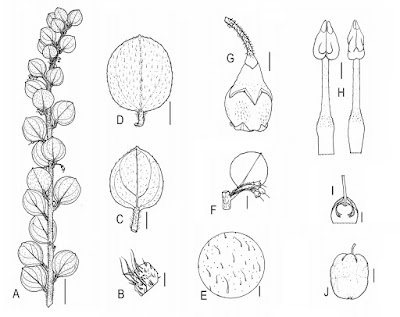

| 1:42a | [Botany • 2020] Diplycosia puradyatmikai (Ericaceae) • A New Species of Diplycosia from Mount Jaya, western New Guinea

Abstract Diplycosia puradyatmikai, a new species of Ericaceae, is described from Mount Jaya in the Indonesian province of Papua, western New Guinea. A detailed description, illustration, and comparisons with the similar species D. kosteri are provided. Keywords: Diplycosia, new species, Papuasia, Indonesia, taxonomy, Ericales, Eudicots Diplycosia puradyatmikai Mustaqim, Utteridge & Heatubun, sp. nov. Type:― INDONESIA. Papua: Mimika Regency, Tembagapura, road from Timika to Tembagapura, Mile 64, ridge north of Army Camp, 2770 m, 22 Nov. 2018, Mustaqim 2234 with Puradyatmika & Dominggus (holotype: BO!, isotypes: FIPIA!, MAN!). Diagnosis:― Similar to D. kosteri Sleumer (1963: 117) in having hairy twigs, the absence of simple fine hairs, calyx with non-glandular bristles, glabrous filaments, the style shorter than 4 mm; but differs in the erect habit (vs scandent in D. kosteri), persistent twig bristles (vs early glabrescent), leaf blades usually broadly-ovate to suborbicular (vs elliptic) and comparatively smaller (0.8–) 1.6–2.8 × (0.7–) 1.5–2.5 cm (vs (2.5–) 2.8–4.5(–5.5) × (1.5–)2–3(–3.2) cm), the corolla tube widest near the base (vs widest near the mouth) with trichomes on the outer surface (vs glabrous), and shorter filaments (2.8–3 vs 3.5 mm long) and anthers 1.2–1.4 mm long (vs 1.8 mm long) (see also Table 1). Etymology:― The epithet refers to the current General Supervisor of Highland Reclamation and Monitoring at the PT Freeport Indonesia Mining Company, Pratita Puradyatmika, who has a great interest in the biodiversity of Mount Jaya, and worked with biologists over many years to undertake biodiversity inventories in and around the region. Distribution and Ecology:― New Guinea: endemic to Mount Jaya. In disturbed mid-montane forest dominated by Nothofagus regeneration; also on ridge shrubbery, with many ericaceous plants including Gaultheria pullei J.J.Sm. (Smith 1915: 7), Rhododendron sp. and other unidentified Diplycosia sp.; 2700−2770 m a.s.l. Wendy A. Mustaqim, Tatik Chikmawati, Timothy M.A. Utteridge and Charlie D. Heatubun. 2020. A New Species of Diplycosia (Ericaceae) from Mount Jaya, western New Guinea. Phytotaxa. 442(2); 52–60. DOI: 10.11646/phytotaxa.442.2.1 | ||||

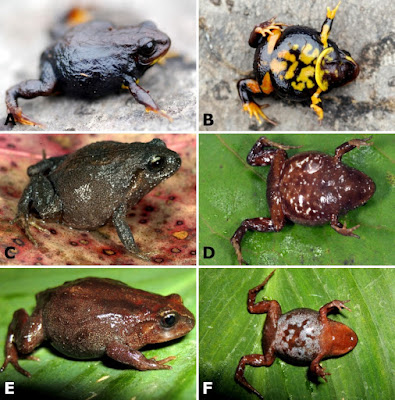

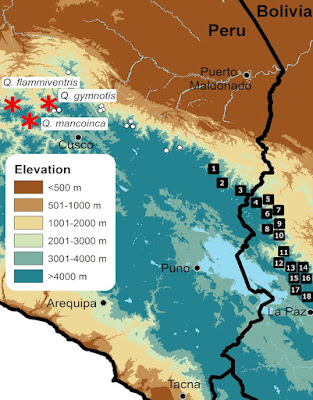

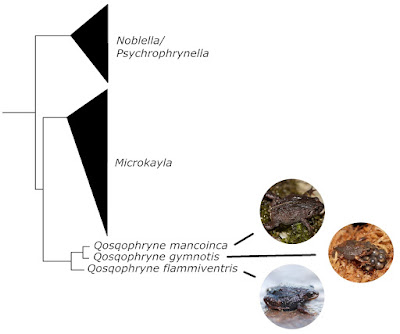

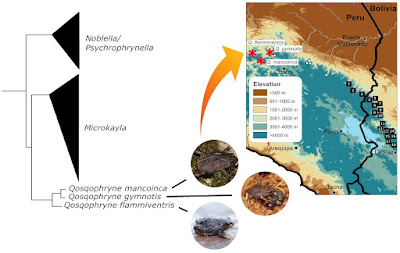

| 2:00a | [Herpetology • 2020] Qosqophryne gen. nov. • A New Genus of Terrestrial-Breeding Frogs (Anura: Terrarana: Strabomantidae: Holoadeninae) from Southern Peru Abstract We propose to erect a new genus of terrestrial-breeding frogs of the Terrarana clade to accommodate three species from the Province La Convención, Department of Cusco, Peru previously assigned to Bryophryne: B. flammiventris, B. gymnotis, and B. mancoinca. We examined types and specimens of most species, reviewed morphological and bioacoustic characteristics, and performed molecular analyses on the largest phylogeny of Bryophryne species to date. We performed phylogenetic analysis of a dataset of concatenated sequences from fragments of the 16S rRNA and 12S rRNA genes, the protein-coding gene cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI), the nuclear protein-coding gene recombination-activating protein 1 (RAG1), and the tyrosinase precursor (Tyr). The three species are immediately distinguishable from all other species of Bryophryne by the presence of a tympanic membrane and annulus, and by males having median subgular vocal sacs and emitting advertisement calls. Our molecular phylogeny confirms that the three species belong to a new, distinct clade, which we name Qosqophryne, and that they are reciprocally monophyletic with species of Microkayla. These two genera (Qosqophryne and Microkayla) are more closely related to species of Noblella and Psychrophrynella than to species of Bryophryne. Although there are no known morphological synapomorphies for either Microkayla or Qosqophryne, the high endemism of their species, and the disjoint geographic distribution of the two genera, with a gap region of ~310 km by airline where both genera are absent, provide further support for Qosqophryne having long diverged from Microkayla. The exploration of high elevation moss and leaf litter habitats in the tropical Andes will contribute to increase knowledge of the diversity and phylogenetic relationships within Terrarana. Keywords: amphibian; Andes; Cusco; high elevation; Neotropical; Qosqophryne; tropical mountain; systematic; taxonomy Taxonomy Qosqophryne new genus Type species. Bryophryne gymnotis Lehr and Catenazzi, 2009 Included species. Qosqophryne flammiventris (Lehr and Catenazzi, 2010), comb. nov.; Q. mancoinca (Mamani, Catenazzi, Ttito, Mallqui, Chaparro, 2017), comb. nov. Diagnosis. (1) Head wider than long, narrower than body, body robust, extremities short; (2) tympanic membrane and annulus present; (3) cranial crests absent; (4) prevomerine teeth and dentigerous process of vomers present (but absent in Q. flammiventris); (5) trips of digits narrow, rounded, circumferential grooves absent, terminal phalanges T-shaped to knobbed; (6) Finger I shorter than Finger II, nuptial pads absent; (7) Toe V shorter than Toe III; (8) fingers and toes with lateral fringes (but absent in Q. flammiventris); (9) subarticular tubercles small, rounded; (10) dorsolateral folds short, discontinuous or continuous; (11) discoidal fold absent (present in Q. mancoinca); (12) trigeminal nerve passing external to m. adductor mandibulae externus (‘S’ condition; Lynch, 1986); (13) snout-vent length from 16.7–19.3 mm in males and 16.0–22.2 mm in females of Q. gymnotis, to 19.6–22.9 mm in males and 23.6–26.5 mm in females of Q. mancoinca; (14) males with median subgular vocal sac and vocal slits, nuptial pads absent; (15) advertisement call whistle-like, composed of a single, tonal note in Q. gymnotis, 2–3 short notes in Q. mancoinca, and 3–4 short notes in Q. flammiventris. ... Etymology. The name refers to the city of Cusco, using the spelling Qosqo which more closely reflects the name in Quechua. Qosqo is used in apposition with phryne, from the greek for “frog”. Thus, the name for the new genus alludes to the geographic distribution of the three known species in the Peruvian Department of Cusco. Distribution, natural history, and conservation. The three species of Qosqophryne occur within a region of ~150 km2 in the upper montane forests and grasslands of the Cordilleras de Urubamba and Cordillera de Vilcabamba, Provincia La Convención, Department Cusco, Peru. These frogs inhabit cloud forests, elfin forests, montane scrub and humid grasslands (puna) from 3270 to 3800 m a.s.l. Similar to other regions in the high Andes, these habitats and their amphibian communities are threatened by pasture burning, climate change and associated expansion of agricultural activities, deforestation, and the fungal disease chytridiomycosis. Although chytridiomycosis has caused the collapse of montane frog communities at several sites in Departamento Cusco, terrestrial-breeding frogs have generally declined the least, and several species challenged in experimental infection trials appears to resist or tolerate infection. Protection of natural habitats will benefit conservation of these frogs. Two of the three species occur within naturally protected areas: Q. gymnotis within the Área de Conservación Privada Abra Málaga, and Q. mancoinca within Machu Picchu Historic Sanctuary. Alessandro Catenazzi, Luis Mamani, Edgar Lehr and Rudolf von May. 2020. A New Genus of Terrestrial-Breeding Frogs (Holoadeninae, Strabomantidae, Terrarana) from Southern Peru. Diversity. 12(5); 184. DOI: 10.3390/d12050184 | ||||

| 2:04a | [Herpetology • 2020] Liopeltis tiomanica • A New Liopeltis Fitzinger, 1843 (Squamata: Colubridae) from Pulau Tioman, Peninsular Malaysia

Abstract Liopeltis is a genus of poorly known, infrequently sampled species of colubrid snakes in tropical Asia. We collected a specimen of Liopeltis from Pulau Tioman, Peninsular Malaysia, that superficially resembled L. philippina, a rare species that is endemic to the Palawan Pleistocene Aggregate Island Complex, western Philippines. We analyzed morphological and mitochondrial DNA sequence data from the Pulau Tioman specimen and found distinct differences to L. philippina and all other congeners. On the basis of these corroborated lines of evidence, the Pulau Tioman specimen is described as a new species, Liopeltis tiomanica sp. nov. The new species occurs in sympatry with L. tricolor on Pulau Tioman, and our description of L. tiomanica sp. nov. brings the number of endemic amphibians and reptiles on Pulau Tioman to 12. Keywords: Reptilia, Liopeltis philippina, Liopeltis tricolor, Palawan, taxonomy

Liopeltis tricolor (part): J.L. Grismer et al. 2004: 275; Grismer 2011: 203. Liopeltis tricolour [sic] (part): Grismer et al. 2006: 178. Etymology. The specific epithet refers to the new species’ type and only known locality on the island of PulauTioman. The specific epithet is feminine, in agreement with the gender of the genus (Poyarkov et al. 2019). Hannah E. Som, L. Lee Grismer, Perry L. Wood, Jr., Evan S. H. Quah, Rafe M. Brown, Arvin C. Diesmos, Jeffrey L. Weinell and Bryan L. Stuart. 2020. A New Liopeltis Fitzinger, 1843 (Squamata: Colubridae) from Pulau Tioman, Peninsular Malaysia. Zootaxa. 4766(3); 472–484. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4766.3.6 | ||||

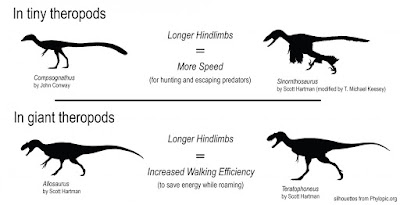

| 3:53a | [Paleontology • 2020] The Fast and the Frugal: Divergent Locomotory Strategies drive Limb Lengthening in Theropod Dinosaurs Abstract Limb length, cursoriality and speed have long been areas of significant interest in theropod paleobiology, since locomotory capacity, especially running ability, is critical in the pursuit of prey and to avoid becoming prey. The impact of allometry on running ability, and the limiting effect of large body size, are aspects that are traditionally overlooked. Since several different non-avian theropod lineages have each independently evolved body sizes greater than any known terrestrial carnivorous mammal, ~1000kg or more, the effect that such large mass has on movement ability and energetics is an area with significant implications for Mesozoic paleoecology. Here, using expansive datasets that incorporate several different metrics to estimate body size, limb length and running speed, we calculate the effects of allometry on running ability. We test traditional metrics used to evaluate cursoriality in non-avian theropods such as distal limb length, relative hindlimb length, and compare the energetic cost savings of relative hindlimb elongation between members of the Tyrannosauridae and more basal megacarnivores such as Allosauroidea or Ceratosauridae. We find that once the limiting effects of body size increase is incorporated there is no significant correlation to top speed between any of the commonly used metrics, including the newly suggested distal limb index (Tibia + Metatarsus/ Femur length). The data also shows a significant split between large and small bodied theropods in terms of maximizing running potential suggesting two distinct strategies for promoting limb elongation based on the organisms’ size. For small and medium sized theropods increased leg length seems to correlate with a desire to increase top speed while amongst larger taxa it corresponds more closely to energetic efficiency and reducing foraging costs. We also find, using 3D volumetric mass estimates, that the Tyrannosauridae show significant cost of transport savings compared to more basal clades, indicating reduced energy expenditures during foraging and likely reduced need for hunting forays. This suggests that amongst theropods, hindlimb evolution was not dictated by one particular strategy. Amongst smaller bodied taxa the competing pressures of being both a predator and a prey item dominant while larger ones, freed from predation pressure, seek to maximize foraging ability. We also discuss the implications both for interactions amongst specific clades and Mesozoic paleobiology and paleoecological reconstructions as a whole. T. Alexander Dececchi, Aleksandra M. Mloszewska, Thomas R. Holtz Jr., Michael B. Habib and Hans C. E. Larsson. 2020. The Fast and the Frugal: Divergent Locomotory Strategies drive Limb Lengthening in Theropod Dinosaurs. PLoS ONE. 15(5): e0223698. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223698 T. rex's long legs were made for marathon walking Research finds leg length gave giant predatory dinosaurs the advantage of efficiency, not speed as previously thought. |

| << Previous Day |

2020/05/14 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |