[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, March 13th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 6:02p | The Fiction of the Science: A Meditation on How Artists & Storytellers Can Advance Technology

In elementary school, a playful teacher gave us an assignment. Everyone was to dream up some sort of amazing invention, then draw both a design and an advertisement for it. It seemed most of my classmates were primed for a future in which sneakers would come equipped with fully operational, built-in wings. I succumbed to peer pressure and turned in an ad showing a laughing, airborne boy, taunting an earthbound adult by dangling his be-winged sneaker-clad foot just a few inches out of reach. My Fleet Foot was awarded a good grade, but I felt no passion for it. The invention that truly captured me was the one depicted in my favorite illustration from Patapoufs et Filifers, the funny French children’s book my father had passed down, about a war between fat and thin people. The thin characters were industrious and highly driven, but the fat ones knew how to live, lounging in feather beds beside wall spigots dispensing hot chocolate. Those spigots were—then and now—a technological advancement I would love to see realized. Robert Wong, are you listening? In the Fiction of Science, the short film above, Wong, a graphic designer and Google Creative Lab’s VP, shows how storytelling can put the spurs to those with the training and know-how to usher these wild-sounding advancements into the real world. Case in point, the cell phone. Martin Cooper, an engineer at Motorola, is widely regarded as the father of the mobile phone, but when we take a broader view, the cell phone actually has two daddies: Cooper and Wah Ming Chang, the artist responsible for many of Star Trek’s iconic props, including the phaser, the tricorder and the communicator—a “portable transceiver device in use by Starfleet crews since the mid-22nd century.” (Not surprisingly, Cooper was a huge Star Trek fan.) Touch screens and 3D fabrications born of hand gestures are among the many creative fictions that have quickly become reality as science and art intermingle on movie sets and in the lab. If you’re inspired to take an active part in this revolution, Google Creative Lab is currently taking applications for The Five, a one-year paid program for five lucky innovators, drawn from a pool of artists, designers, filmmakers, developers, and other talented, multi-dextrous makers. Related Content: Pixar’s 22 Rules of Storytelling Learn Python: A Free Online Course from Google John Berger (RIP) and Susan Sontag Take Us Inside the Art of Storytelling (1983) Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and theater maker whose play Zamboni Godot is playing in New York City through March 18. Follow her @AyunHalliday. The Fiction of the Science: A Meditation on How Artists & Storytellers Can Advance Technology is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

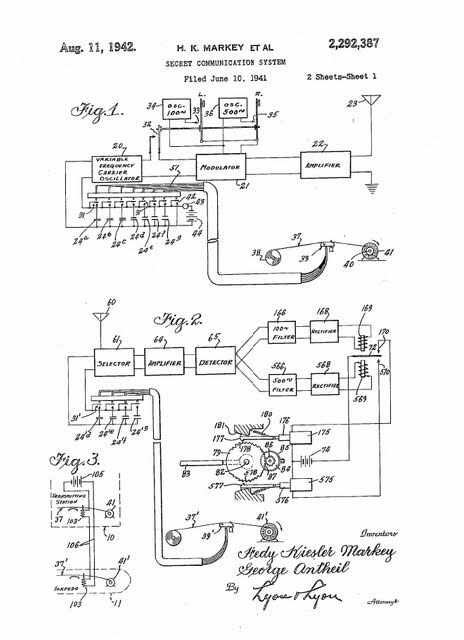

| 6:21p | How Sultry 1940s Film Star Hedy Lamarr Helped Invent the Technology Behind Wi-Fi & Bluetooth During WWII   A certain ideal of America holds that an immigrant who arrives in that land of opportunity can, with hard work and luck, completely remake themselves, even into an A-list movie star or an inventor of heretofore unimagined new things. Hedy Lamarr, by this reckoning, ranks among the ideal Americans: born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, she arrived in Hollywood in 1938 and reigned, under her new name granted by movie mogul Louis B. Mayer, as perhaps the most beautiful face on the silver screen for the next dozen years. A reluctant star since her early role in the scandalous Czech film Ekstase and in America never quite able to escape typecasting as the mysterious, exotic beauty opposite a “real” actor, the bored Lamarr occupied her mind by turning to invention. Working away at her drafting table instead of making the nightly Hollywood party rounds, Lamarr came up with everything from dissolving soda tablets to improved traffic signals and tissue boxes to a “skin-tautening technique based on the principles of the accordion.” But her place in the canon of American inventors rests on an idea that came out of a conversation with composer George Antheil. Married back in Austria to arms dealer Friedrich Mandl, she’d overheard conversations, according to her New York Times obituary, between her then-husband and many Nazi-higher ups “who seemed to place great value on creating some sort of device that would permit the radio control of airborne torpedoes and reduce the danger of jamming. She and Antheil got to discussing all this. The idea, they decided, was to defeat jamming efforts by sending synchronized radio signals on various wavelengths to missiles, which could then be directed to hit their mark.” Lamarr filed this ingenious patent for a “frequency-hopping” communication system in 1942, but it raised no military interest until the Cuban Missile Crisis twenty years later, when the Navy started using the technology on their ships. It evolved in the decades thereafter, ultimately becoming an indispensable element of such technologies in widespread use today as wi-fi and Bluetooth. Having signed her invention over to the military, Lamarr never made a dime from it herself, but in 1996, four years before she died, she did receive the Electronic Future Foundation’s Pioneer Award. “It’s about time,” she said when she heard the news.  More recently, historian Richard Rhodes told the story of Lamarr’s inventing life in full with the book Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World. “Hedy realized that what she came up with was important but I don’t think she knew how important it was going to be,” said her son Anthony Loder. “The definition of importance is the more people that it affects over the longer period of time. The longer this goes on and the more people it affects the more important she will be.” Lamarr herself, in response to praise for her contribution to communication technology received in her lifetime, explained it as merely the result of following her instincts: “Improving things comes naturally to me.” Related Content: Watch The Strange Woman, the 1946 Noir Film Starring Hedy Lamarr Mark Twain’s Patented Inventions for Bra Straps and Other Everyday Items Percussionist Marlon Brando Patented His Invention for Tuning Conga Drums Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. How Sultry 1940s Film Star Hedy Lamarr Helped Invent the Technology Behind Wi-Fi & Bluetooth During WWII is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:30p | An Animated Introduction to Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent and How the Media Creates the Illusion of Democracy

For nearly as many years as he’s occupied the public eye, famed linguist and anarchist philosopher Noam Chomsky has made claims that might have discredited other academics. Perhaps his many books, articles, lectures, interviews, etc. carry such weight because of his “famed linguist” status and his longtime tenure at MIT. But there’s more to his longevity as a respected critic of U.S. state power. His voice also carries significant authority because he substantiates his arguments with erudite, granular analyses of economic theory, history, and political philosophy. We’ve seen him do exactly this in his fierce opposition to the Vietnam War at the beginning of his activist career, and in his critiques of proxy wars, imperialistic repression, and corporate resource grabs in Latin America and Southeast Asia in decades since. When it comes to the U.S. domestic scene, one of Chomsky’s most pointed and continually relevant critiques addresses the way in which we’re led to believe the country’s actions overseas justify themselves, as well as its actions upon its own citizens. We might debate whether the U.S. is a democracy or a republic, but according to Chomsky, both notions may well be illusory. Instead, Chomsky argues in Manufacturing Consent—his 1988 critique of “the political economy of the mass media” with Edward S. Herman—that the mass media sells us the idea that we have political agency. Their “primary function… in the United States is to mobilize support for the special interests that dominate the government and the private sector.” Those interests may have changed or evolved quite a bit since 1988, but the mechanisms of what Chomsky and Herman identify as “effective and powerful ideological institutions that carry out a system-supportive propaganda function” might work in the age of Twitter just as they did in one dominated by network and cable news. Those mechanisms largely divide into what the authors called the “Five Filters.” The video at the top of the post, narrated by Democracy Now’s Amy Goodman, provides a quick introduction to them, in a jarring animated sequence that’s part Monty Python, part Residents video. See the five filters listed below in brief, with excerpts from Goodman’s commentary:

Chomsky and Herman’s book offers a surgical analysis of the ways corporate mass media “manufactures consent” for a status quo the majority of people do not actually want. Yet for all of the recent agonizing over mass media failure and complicity, we don’t often hear references to Manufacturing Consent these days. This may have something to do with the book’s dated examples, or it may testify to Chomsky’s marginalization in mainstream political discourse, though he would be the first to note that his voice has not been suppressed. It may also be the case that media theory and criticism like Chomsky’s, or the work of Marshall McLuhan, Theodor Adorno, or Jean Baudrillard (all very different kinds of thinkers), has fallen out of favor in a 140-character world. In the late-80s and 90s, however, such theory received a good deal of attention, and Chomsky appeared in the many venues you’ll see in the short video above, excerpted from an almost 3-hour 1992 documentary called Manufacturing Consent, a film made by “die-hard fans,” wrote Colin Marshall in an earlier post, that “curates instances of Chomsky going from interview to interview, debate to debate, forum to forum, making sharp-sounding points about the relationship between business elites and the media.” Our desire for instant reward and settled opinion may have overtaken our ability to subject the entire phenomenon of mass media to critical analysis, as we leap from cliffhanger to cliffhanger and crisis to crisis. But should we take the time to watch this film and, preferably also, read Chomsky’s book, we may find ourselves somewhat better equipped to evaluate the onslaught of propaganda to which we’re subjected on what seems like an hourly basis. Related Content: Noam Chomsky Defines What It Means to Be a Truly Educated Person Noam Chomsky & Michel Foucault Debate Human Nature & Power (1971) Noam Chomsky Talks About How Kids Acquire Language & Ideas in an Animated Video by Michel Gondry Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness An Animated Introduction to Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent and How the Media Creates the Illusion of Democracy is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/03/13 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |