[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, March 21st, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 6:58a | I’m Just a Pill: A Schoolhouse Rock Classic Gets Reimagined to Defend Reproductive Rights in 2017

Like many American children of the 70s and 80s, my understanding of how our government is supposed to function was shaped by Schoolhouse Rock. Immigration, separation of legislative, executive and judicial powers and of course, the promise of the Constitution (“a list of principles for keepin’ people free”) were just a few of the topics the animated musical series covered with clarity and wit. The new world order in which we’ve recently found ourselves suggests that 2017 would be a grand year to start rolling out more such videos. The Lady Parts Justice League, a self-declared “cabal of comics and writers exposing creeps hellbent on destroying access to birth control and abortion” leads the charge with the above homage to Schoolhouse Rock’s 1976 hit, “I’m Just a Bill,” recasting the original’s glum aspirant law as a feisty Plan B contraceptive pill. The red haired boy who kept the bill company on the steps of the Capital is now a teenage girl, confused as to how any legal, over-the-counter method for reducing the risk of unwanted pregnancy could have so many enemies. As with the original series, the prime objective is to educate, and comic Lea DeLaria’s Pill happily obliges, explaining that while people may disagree as to when “life” begins, it’s a scientific fact that pregnancy begins when a fertilized egg lodges itself in the uterus. (DeLaria plays Big Boo on Orange is the New Black, by the way.) That process takes a while—72 hours to be exact. Plenty of time for the participants to scuttle off to the drugstore for emergency contraception, aka Plan B, the so called “morning-after” pill. As per the drug’s website, if taken within 72 hours after unprotected sex, Plan B can reduce the risk of pregnancy by up to 89%. Taken within 24 hours, it is about 95% effective. And yes, teenagers can legally purchase it, though Teen Vogue has reported on numerous stores who’ve made it difficult, if not impossible, for shoppers to gain access to the pill. (The Reproductive Justice Project encourages consumers to help them collect data on whether Plan B is correctly displayed on the shelves as available for sale to any woman of childbearing age.) There’s a helpful football analogy for those who may be a bit slow in understanding that Plan B is indeed a bonafide contraceptive, and not the abortifacient some mistakenly make it out to be. It’s NSFW, but only just, as a team of cartoon penis-outlines push down the field toward the uterine wall in the end zone. The other bills who once stood in line awaiting the president’s signature have been reimagined as sperm, while songwriter Holly Miranda pays tribute to Dave Frishberg’s lyrics with a pizzazz worthy of the original: I’m just a pill A helpful birth control pill No matter what they say on Capital Hill So now you know my truth I’m all about prevention If your condom breaks I’m here for intervention Join me take a stand today I really hope and pray that you will Drop some facts Tell the world I’m a pill. Let’s hope the resistance yields more catchy, educational animations! And here, for comparison’s sake, is the magnificent original: Via BUST Magazine Related Content: Schoolhouse Rock: Revisit a Collection of Nostalgia-Inducing Educational Videos Conspiracy Theory Rock: The Schoolhouse Rock Parody Saturday Night Live May Have Censored Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday. I’m Just a Pill: A Schoolhouse Rock Classic Gets Reimagined to Defend Reproductive Rights in 2017 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

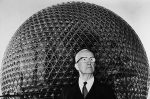

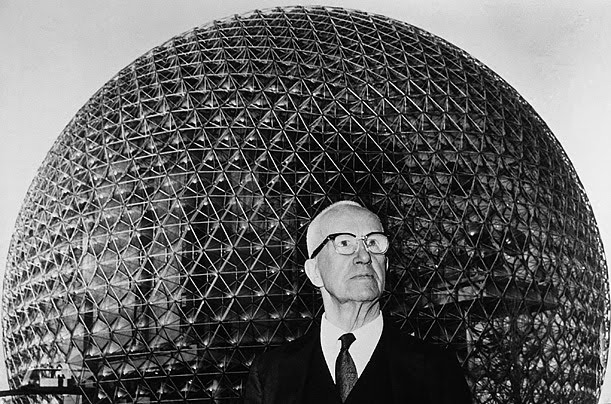

| 11:30a | Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Sleep Plan: He Slept Two Hours a Day for Two Years & Felt “Vigorous” and “Alert”   One potential drawback of genius, it seems, is restlessness, a mind perpetually on the move. Of course, this is what makes many celebrated thinkers and artists so productive. That and the extra hours some gain by sacrificing sleep. Voltaire reportedly drank up to 50 cups of coffee a day, and seems to have suffered no particularly ill effects. Balzac did the same, and died at 51. The caffeine may have had something to do with it. Both Socrates and Samuel Johnson believed that sleep is wasted time, and “so for years has thought grey-haired Richard Buckminster Fuller,” wrote Time magazine in 1943, “futurific inventor of the Dymaxion house, the Dymaxion car and the Dymaxion globe.” Engineer and visionary Fuller intended his “Dymaxion” brand to revolutionize every aspect of human life, or—in the now-slightly-dated parlance of our obsession with all things hacking—he engineered a series of radical “lifehacks.” Given his views on sleep, that seemingly essential activity also received a Dymaxion upgrade, the trademarked name combining “dynamic,” “maximum,” and “tension.” “Two hours of sleep a day,” Fuller announced, “is plenty.” Did he consult with specialists? Medical doctors? Biologists? Nothing as dull as that. He did what many a mad scientist does in the movies. (In the search, as Vincent Price says at the end of The Fly, “for the truth.”) He cooked up a theory, and tested it on himself. “Fuller,” Time reported, “reasoned that man has a primary store of energy, quickly replenished, and a secondary reserve (second wind) that takes longer to restore.” He hypothesized that we would need less sleep if we stopped to take a nap at “the first sign of fatigue.” Fuller trained himself to do just that, forgoing the typical eight hours, more or less, most of us get per night. He found—as have many artists and researchers over the years—that “after a half-hour nap he was completely refreshed.” Naps every six hours allowed him to shrink his total sleep per 24-hour period to two hours. Did he, like the 50s mad scientist, become a tragic victim of his own experiment? No danger of merging him with a fly or turning him invisible. The experiment’s failure may have meant a day in bed catching up on lost sleep. Instead, Fuller kept up it for two full years, 1932 and 1933, and reported feeling in “the most vigorous and alert condition that I have ever enjoyed.” He might have slept two hours a day in 30 minute increments indefinitely, Time suggests, but found that his “business associates… insisted on sleeping like other men,” and wouldn’t adapt to his eccentric schedule, though some not for lack of trying. In his book BuckyWorks J. Baldwin claims, “I can personally attest that many of his younger colleagues and students could not keep up with him. He never seemed to tire.” A research organization looked into the sleep system and “noted that not everyone was able to train themselves to sleep on command.” The point may seem obvious to the significant number of people who suffer from insomnia. “Bucky disconcerted observers,” Baldwin writes, “by going to sleep in thirty seconds, as if he had thrown an Off switch in his head. It happened so quickly that it looked like he had had a seizure.” Buckminster Fuller was undoubtedly an unusual human, but human all the same. Time reported that “most sleep investigators agree that the first hours of sleep are the soundest.” A Colgate University researcher at the time discovered that “people awakened after four hours’ sleep were just as alert, well-coordinated physically and resistant to fatigue” as those who slept the full eight. Sleep research since the forties has made a number of other findings about variable sleep schedules among humans, studying shift workers’ sleep and the so-called “biphasic” pattern common in cultures with very late bedtimes and siestas in the middle of the day. The success of this sleep rhythm “contradicts the normal idea of a monophasic sleeping schedule,” writes Evan Murray at MIT’s Culture Shock, “in which all our time asleep is lumped into one block.” Biphasic sleep results in six or seven hours of sleep rather than the seven to nine of monophasic sleepers. Polyphasic sleeping, however, the kind pioneered by Fuller, seems to genuinely result in even less needed sleep for many. It’s an idea that’s only become widespread “within roughly the last decade,” Murray noted in 2009. He points to the rediscovery, without any clear indebtedness, of Fuller’s Dymaxion system by college student Maria Staver, who named her method “Uberman,” in honor of Nietzsche, and spread its popularity through a blog and a book. Murray also reports on another blogger, Steve Pavlina, who conducted the experiment on himself and found that “over a period of 5 1/2 months, he was successful in adapting completely,” reaping the benefits of increased productivity. But like Fuller, Pavlina gave it up, not for “health reasons,” but because, he wrote, “the rest of the world is monophasic” or close to it. Our long block of sleep apparently contains a good deal of “wasted transition time” before we arrive at the necessary REM state. Polyphasic sleep trains our brains to get to REM more quickly and efficiently. For this reason, writes Murray, “I believe it can work for everyone.” Perhaps it can, provided they are willing to bear the social cost of being out of sync with the rest of the world. But people likely to practice Dymaxion Sleep for several months or years probably already are. Related Content: The Power of Power Naps: Salvador Dali Teaches You How Micro-Naps Can Give You Creative Inspiration Bertrand Russell & Buckminster Fuller on Why We Should Work Less, and Live & Learn More Everything I Know: 42 Hours of Buckminster Fuller’s Visionary Lectures Free Online (1975) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Sleep Plan: He Slept Two Hours a Day for Two Years & Felt “Vigorous” and “Alert” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:30p | Hear Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” Shifted from Minor to Major Key, and Radiohead’s “Creep” Moved from Major to Minor

A few years ago, we shared a version of R.EM.’s 1991 alternative hit “Losing My Religion” as reworked from a minor to a major key through digital processing by Ukranian musician Oleg Berg and his daughter Diana. Many people thought the project a travesty and railed against its violation of R.E.M.’s emotional intent. But the stronger the reactions, the more they seemed to validate Berg’s tacit argument about the important differences between major and minor keys. We know that, in general, minor keys convey sadness, dread, or moody intensity, all familiar colors in the R.E.M. palate. Major keys, on the other hand—as in the band’s inexplicably bouncy “Shiny Happy People”—tend to evoke… shininess and happiness. Why is this? Goldsmiths University Music Psychology Professor Vicky Williamson has an ambivalent explanation at the NME blog. Her answer: the association seems to be cultural but also, perhaps, biological. “Scientists have shown that the sound spectra—the profile of sound ingredients—that make up happy speech are more similar to happy music than sad music and vice versa.” This thesis may reduce down to a “water is wet” observation. A more interesting way of thinking of it comes from Aristotle, who “suspected that the emotional impact of music was at least partly down to the way it mimicked our own vocalizations when we squeal for joy or cry out in anger.” Do these expressions always correspond to major or minor scales or intervals? No. Emotions, like colors, have subtleties of shading, contrast, and hue. Williamson names some notable exceptions, like The Smiths’ “I Know It’s Over,” a song in a major key that is almost comically morbid and maudlin. These may serve to prove the rule, achieving their unsettling effect by playing with our expectations. In general, as you will learn from the video above from Minnesota Public Radio—in which a lumberjack explains the distinctions to an animated blue bird—major and minor keys, scales, intervals, and chords are “tools composers use to give their music a certain mood, atmosphere, and strength.” If you were to ask for a song that contains these qualities in abundance, you might get in reply Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” which, like Beethoven’s 9th Symphony or most classical opera, relies on exaggerated quiet-to-loud dynamics for its dramatic effect. But it also uses a minor key as an essential vehicle for its anxiety and rage. So important to the song is this element, in fact, that when shifted into a major key, as Berg has done at the top of the post, it sounds nearly incoherent. The clarity with which “Smells Like Teen Spirit” communicates angst and confusion evaporates, especially in the song’s verses. The digital artifacts of Berg’s processing become more evident here, perhaps because the change in key is so destructive to the melody. Can we closely correlate this loss of melodic integrity to the critical importance the minor scale plays in this song in particular? I would assume so, but let’s look at the example of a similar type of moody, quiet-loud alt-rock song from around the same time period, Radiohead’s “Creep.” Here’s one of those exceptions, originally written in a major key, which may account for the pleasant, dreamlike quality of its verses. That quality doesn’t necessarily disappear when we hear the song rendered in a minor key. But the chorus, underneath the digital distortion, loses the sense of anguished triumph with which Thom Yorke imbued his defiant declaration of creepiness. In the case of the original “Creep,” the G major key seems to push against our expectations, and gives a song about self-loathing an unsettling sweetness that is indeed kinda creepy. (And perhaps helped Prince to turn the song into a genuinely uplifting gospel hymn). What seems clear in the Nirvana and Radiohead examples is that the choice of key determines in large part not only our emotional responses to a song, but also our responses to deviations from the norm. But those norms are “mostly down to learned associations,” writes Williamson, “both ancient and modern.” Perhaps she’s right. University of Toronto Music Psychologist Glenn Schellenberg has noticed that contemporary music has trended more toward minor keys in the past few decades, and that “people are responding positively to music that has these characteristics that are associated with negative emotions.” Does this mean we’re getting sadder? Schellenberg instead believes it’s because we associate minor scales with sophistication and major scales with “unambiguously happy-sounding music” like “The Wheels on the Bus” and other children’s songs. “The emotion of unambiguous happiness is less socially acceptable than it used to be,” notes NPR. “It’s too Brady Bunch, not enough Modern Family.” Maybe we’ve grown cynical, but the trend allows brilliant rock composers like Radiohead’s Johnny Greenwood to do all sorts of odd, unsettling things with major and minor modulation. And it made “Shiny Happy People” stick out like a shockingly joyful sore thumb upon its release in 1991, though at the time the mope of grunge and 90s alt-rock had not yet dominated the airwaves. Now we rarely hear such earnest, “unambiguously happy-sounding” music these days outside of Sesame Street. Find more of Berg’s major-to-minor and vice versa reworkings at his Youtube channel. Related Content: R.E.M.’s “Losing My Religion” Reworked from Minor to Major Scale The Beatles’ “Hey Jude” Reworked from Major to Minor Scale; Ella’s “Summertime” Goes Minor to Major Patti Smith’s Cover of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” Strips the Song Down to its Heart Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Hear Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” Shifted from Minor to Major Key, and Radiohead’s “Creep” Moved from Major to Minor is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

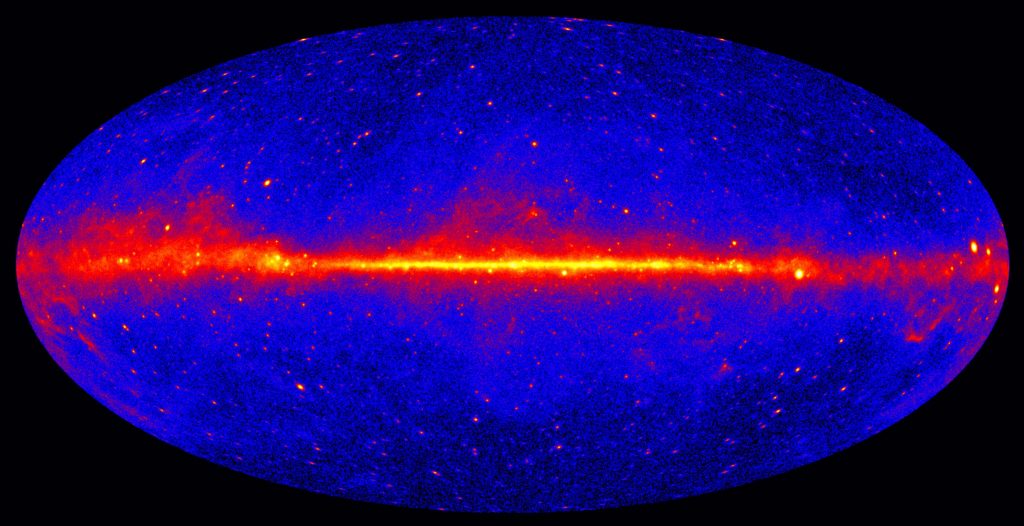

| 5:26p | NASA’s New Online Archive Puts a Wealth of Free Science Articles Online  Since our website took flight a decade ago, we’ve kept you apprised of the free offerings made available by NASA–everything from collections of photography and space sounds, to software, ebooks, and posters. But there’s one item we missed last summer (blame it on the heat!). And that’s NASA PubSpace, an online archive that gives you free access to science journal articles funded by the space agency. Previously, these articles were hidden behind paywalls. Now, “all NASA-funded authors and co-authors … will be required to deposit copies of their peer-reviewed scientific publications and associated data into” NASA PubSpace. This project grew out of the Obama administration’s Open Science Initiative, designed to increase public access to federally funded research and make it easier for scientists to build upon existing research. You can search through NASA’s archive here. Follow Open Culture on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Google Plus, and Flipboard and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. To make sure that our posts definitely appear in your Facebook newsfeed, just follow these simple steps. If you’d like to help support Open Culture, please sign up for a 30-day free trial from Audible.com or The Great Courses Plus. You will get free audio books and free courses in return. No strings attached. Related Content: NASA Its Software Online & Makes It Free to Download NASA Puts Online a Big Collection of Space Sounds, and They’re Free to Download and Use NASA Releases 3 Million Thermal Images of Our Planet Earth Free NASA eBook Theorizes How We Will Communicate with Aliens NASA Archive Collects Great Time-Lapse Videos of our Planet Great Cities at Night: Views from the International Space Station NASA Presents “The Earth as Art” in a Free eBook and Free iPad App NASA’s New Online Archive Puts a Wealth of Free Science Articles Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00p | How to Tell a Good Story, as Explained by George Saunders, Ira Glass, Ken Burns, Scott Simon, Catherine Burns & Others

All of us instinctively respond to stories. This has both positive and negative effects, but if we don’t understand it about ourselves, we’ve won’t fully understand why people believe what they believe and do what they do. Even given the deep human attachment to narrative, can we clearly explain what a story is, or how to tell one? Acclaimed author George Saunders has given the subject a great deal of thought, some of which he lets us in on in the short film above, which Josh Jones previously wrote about here on Open Culture. “A good story,” he tells us, says “at many different levels, ‘We’re both human beings. We’re in this crazy situation called life that we don’t really understand. Can we put our heads together and confer about it at a very high, non-bullshitty level?'”

At this point in his career, Saunders has tried out that approach to story using numerous different techniques and in a variety of different contexts, most recently in his new novel Lincoln in the Bardo, which takes place in the aftermath of the assassination of the titular sixteenth President of the United States. Few living creators understand the appeal of American history as a trove of story material better than Ken Burns, author of long-form documentaries like Jazz, Baseball, and The Civil War, who finds that its “good guys have serious flaws and the villains are very compelling.” And though he ostensibly works with only the facts, he acknowledges that “all story is manipulation,” some of it desirable manipulation and some of it not so much, with the challenge of telling the difference falling to the storyteller himself. “The common story,” Burns says, “is ‘one plus one equals two.’ We get it. But all stories — the real, genuine stories — are about one and one equaling three.” Where his mathematical formula for storytelling emphasizes the importance of the unexpected, the one offered by Andrew Stanton, director of Pixar films like Finding Nemo, WALL-E, and John Carter, emphasizes the importance of a “well-organized absence of information.” In the TED Talk just above (which opens with a potentially NSFW joke), he suggests always giving the audience “two plus two” instead of four, encouraging the audience to do the satisfying work of putting the details of the story together themselves while never letting them realize they’re doing any work at all. “Drama is anticipation mingled with uncertainty,” said the playwright William Archer. Stanton quotes it in his talk, and the notion also seems to underlie the views on storytelling held by This American Life creator Ira Glass. In the interview above, he describes the process of telling a story as recounting a sequence of actions, of course, but also continually throwing out questions and answering them all along the way, oscillating between actions in the story and moments of reflection on those actions which cast a little light on their meaning — a form surely familiar to anyone who’s heard so much as a segment of his radio show. And how do you become as skilled as he and his team at telling stories? Do what he did: tell a huge number of them, telling and telling and telling until you develop the killer instinct to mercilessly separate the truly compelling ones from the rest. Glass illustrates the benefits of his lessons by playing some tape of a news report he produced early in his career, highlighting all the ways in which he failed to tell its story properly. He turned out to be cut out for something slightly different than straight-up reporting, a job of which reporters like Scott Simon of National Public Radio’s Weekend Edition have made an art. Simon takes his storytelling process apart in three and a half minutes in the video just above: beyond providing such essentials as a strong beginning, vivid details, and a point listeners can take away, he says, you’ve also got to consider the way you deliver the whole package. Ideally, you’ll tell your story in “short, breathable sections,” which creates an overall rhythm for the audience to follow, whether they’re sitting on the barstool beside you or tuned in on the other side of the world. What else does a good story need? Conflict. Tension. The feeling of “seeing two opposing forces collide.” Honesty. Grace. The ring of truth. All these qualities and more come up in the Atlantic‘s “Big Question” video above, which asks a variety of notables to name the most important element of a good story. Responders include House of Cards writer and producer Beau Willimon, The Moth artistic director Catherine Burns, PBS president Paula Kerger, and former Disney CEO Michael Eisner. Since humans have told stories since we first began, as Saunders put it, conferring about this crazy situation called life, all manner of storytelling rules, tips, and tricks have come and gone, but the core principles have remained the same. As to whether we now understand life any better… well, isn’t that one of those unanswered questions that keeps us on the edge of our seats? Related Content: George Saunders Demystifies the Art of Storytelling in a Short Animated Documentary Ira Glass, the Host of This American Life, Breaks Down the Fine Art of Storytelling Ken Burns on the Art of Storytelling: “It’s Lying Twenty-Four Times a Second” Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 Tips on How to Write a Good Short Story Kurt Vonnegut Diagrams the Shape of All Stories in a Master’s Thesis Rejected by U. Chicago Pixar & Khan Academy Offer a Free Online Course on Storytelling John Berger (RIP) and Susan Sontag Take Us Inside the Art of Storytelling (1983) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. How to Tell a Good Story, as Explained by George Saunders, Ira Glass, Ken Burns, Scott Simon, Catherine Burns & Others is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/03/21 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |