[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, May 16th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 5:06p | Meet the Iconic Figures on the Cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band June 1 will mark the 50th anniversary of the release of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, an album considered revolutionary in every respect. Everything from the music itself, down to the album’s cover design, broke new ground. To commemorate the upcoming anniversary, the BBC has started to release a series of videos introducing you to the 60+ figures who appeared in the cutout cardboard collage that graced the album’s iconic cover. (See a mapping of the figures here.) Some of the figures are enduring legends–Carl Jung, Marilyn Monroe and James Joyce. Others (e.g., Tommy Handley, Bobby Breen and Tom Mix) have faded into obscurity. Up top, watch the video featuring Bob Dylan. No stranger, right? Down below, see the video on Aubrey Beardsley, the English artist who created striking illustrations for works by Edgar Allan Poe and Oscar Wilde, both also featured in the collage. At the bottom, see a clip on pioneering electronic composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. The BBC will be adding yet more videos here. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you’d like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: How The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band Changed Album Cover Design Forever Oscar Wilde’s Play Salome Illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley in a Striking Modern Aesthetic (1894) Meet the Iconic Figures on the Cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:35p | The MC5 Performs at the 1968 Chicago Democratic National Convention, Right Before All Hell Breaks Loose With some rare exceptions (Sid and Nancy, I’m Not There, maybe Walk the Line and Cadillac Records), biopics usually stumble badly when they try to recreate the personalities and atmospheres of famous musicians. For this reason I am grateful that no studio has yet attempted a narrative of one of my favorite bands, the not-quite-famous MC5. On the other hand, it’s hard to believe there’s no script in development somewhere. If there’s one band whose story—and music—deserves a wider audience, it’s this one. Sadly, guitarist Wayne Kramer has suppressed a very well-reviewed documentary that might do them as much justice as any film can. Formed in Lincoln Park Michigan in 1964, the “Motor City 5” became synonymous with Detroit’s leftist political scene. They were also some of the most uncompromising garage rockers to emerge from the era, along with proto-punks The Stooges, with whom they often performed. By the time of the infamous 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago—well-known for the brutal attacks of police against thousands of aggrieved protesters—the MC5 had become heavily influenced by Fred Hampton and Huey Newton. Under their manager John Sinclair, they became prominent representatives of the “White Panthers,” an anti-racist analogue of the Black Panthers formed on a suggestion of Newton’s. In September of 1968, Sinclair would be indicted for taking part in the bombing a CIA office in Ann Arbor. But exactly one month prior, he presided over the MC5’s appearance at the riotous Chicago Democratic National Convention. The band was booked as part of Abbie Hoffman’s attempt to stage a “Festival of Life,” bringing 100,000 young people to the city “for five days of peace, love, and music,” writes the site Chicago ’68, to “redirect youth culture and music toward political ends.” Fittingly, perhaps, the MC5 was the only band that showed up after Hoffman and his Yippies failed to secure the permits. They played for less than an hour to a crowd of a few thousand. Kramer remembered the day in a 2008 interview:

The only film we seem to have of the event is silent surveillance footage at the top of the post. Further down, see clips of the rioting that ensued, with the band’s hit “Kick Out the Jams” played over it. And just below, see a video of them playing the song over a backdrop of riot footage. They released their debut album, Kick Out the Jams , the following year. It was an uneven collection of performances, but “when they got it right,” says Michael Hann, “they simply got it completely right.” It was certainly their philosophy to go all in. As Kramer described it, “You have to come early, and you have to stay late. The song doesn’t say, ‘Slide out the jams.” It doesn’t say, ‘Stroll out the jams.” It says, ‘Kick out the jams!’”

What I find fascinating about the emergence of the MC5 at this time in history is how great of a contrast they presented to the weary blues of the Rolling Stones, who became grimly linked in ’69 at Altamont with the cynical end of flower power. Despite their association with the violent spectacle of the DNC riots—another sign of the hippie apocalypse—the MC5 became the soundtrack for people power, and in a way bridged the R&B, garage rock, psychedelia, punk, and metal of the gritty 1970s to come. But addiction, political repression, and censorship killed the band a few years later. Lead singer Rob Tyner died in 1991, and guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, who married Patti Smith, passed away in 1994. Kramer has carried on, and still tours (and gives lectures). When he revisited the DNC in 2008 for an unofficial performance and anti-war protest, he reflected on the politics of the day. “It will be helpful not to have to battle as hard as we have with the Bush administration,” he told The Huffington Post, “but Barack Obama cannot save us. It’s really a matter of people themselves taking action in their own neighborhoods, at their own jobs, in their own homes, with their own friends, their own co-workers, to move us into the future, a more just world.” The people power the MC5 represented lives on even into this grim era, and the band itself will always live in legend, if not—for good or ill—in cinema. Related Content: A Gallery of Visually Arresting Posters from the May 1968 Paris Uprising New Jim Jarmusch Documentary on Iggy Pop & The Stooges Now Streaming Free on Amazon Prime Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The MC5 Performs at the 1968 Chicago Democratic National Convention, Right Before All Hell Breaks Loose is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

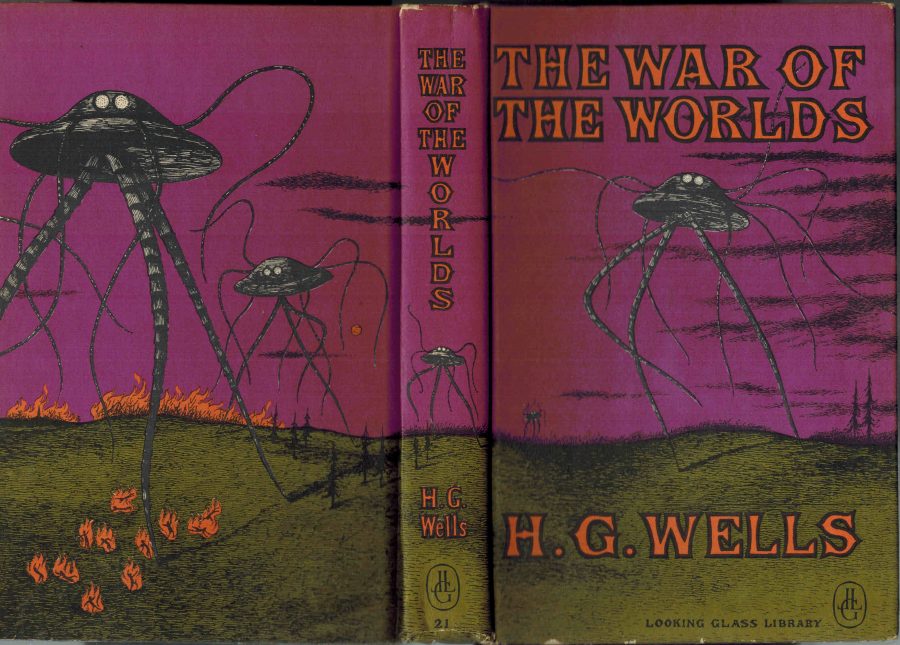

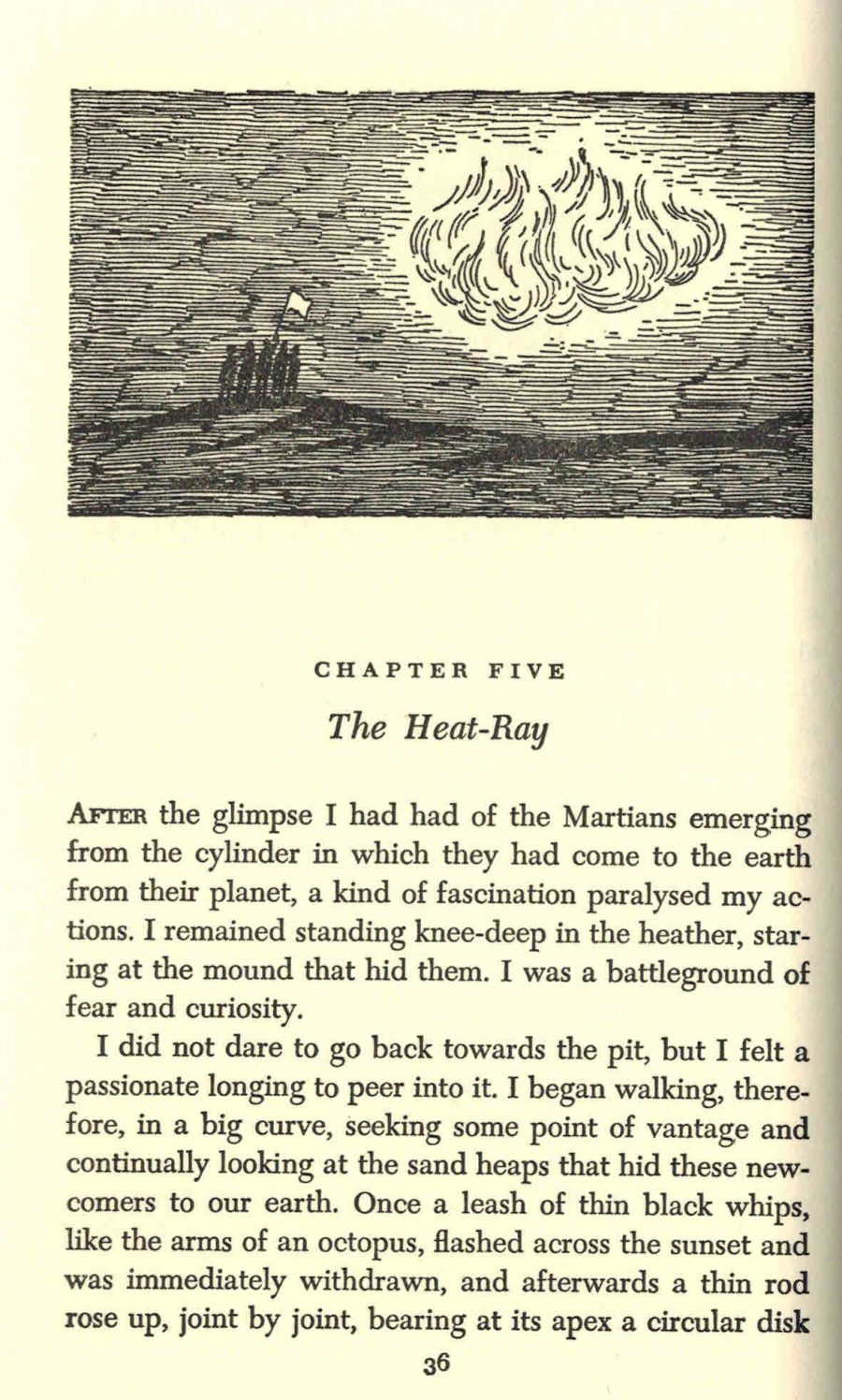

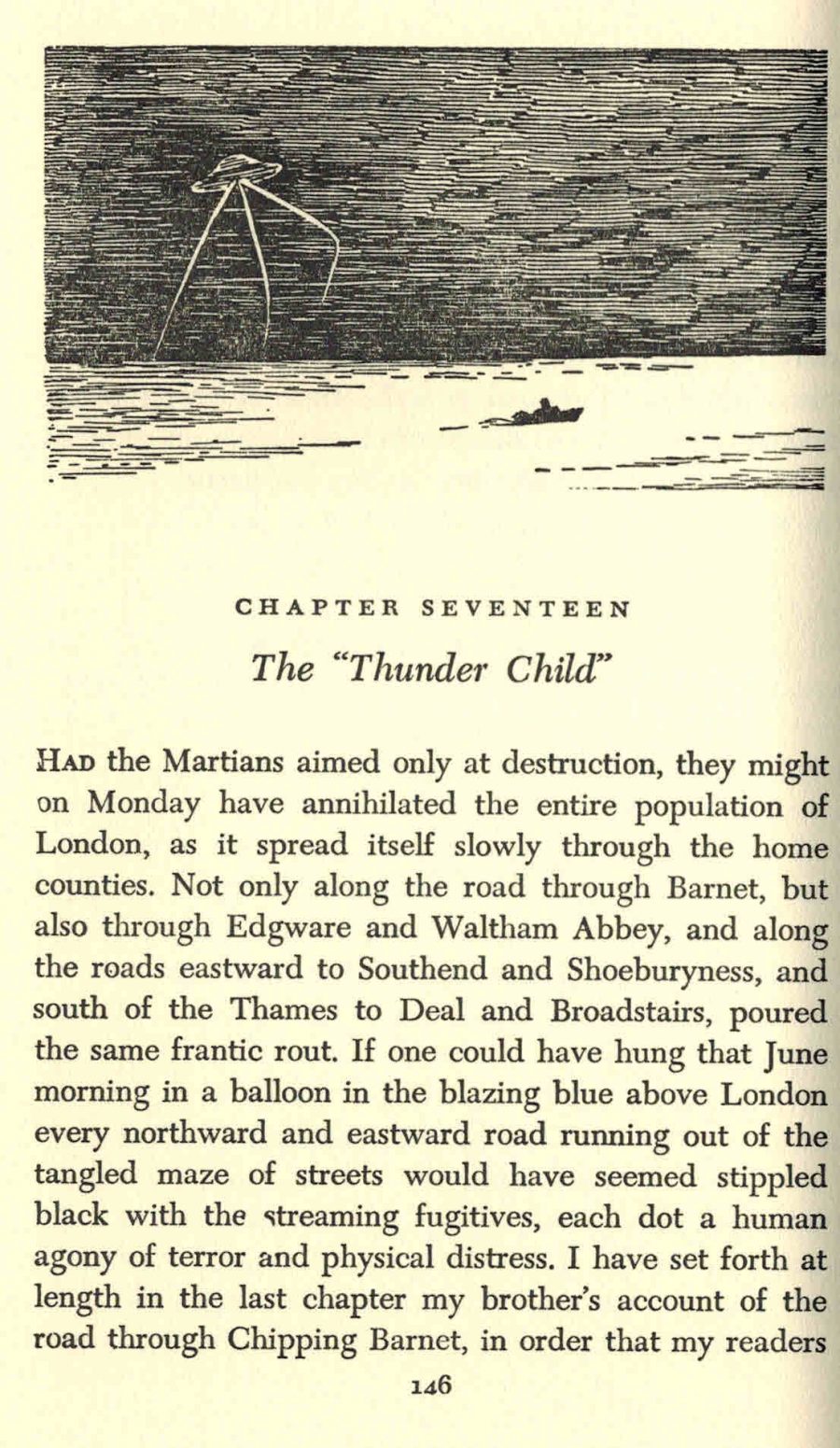

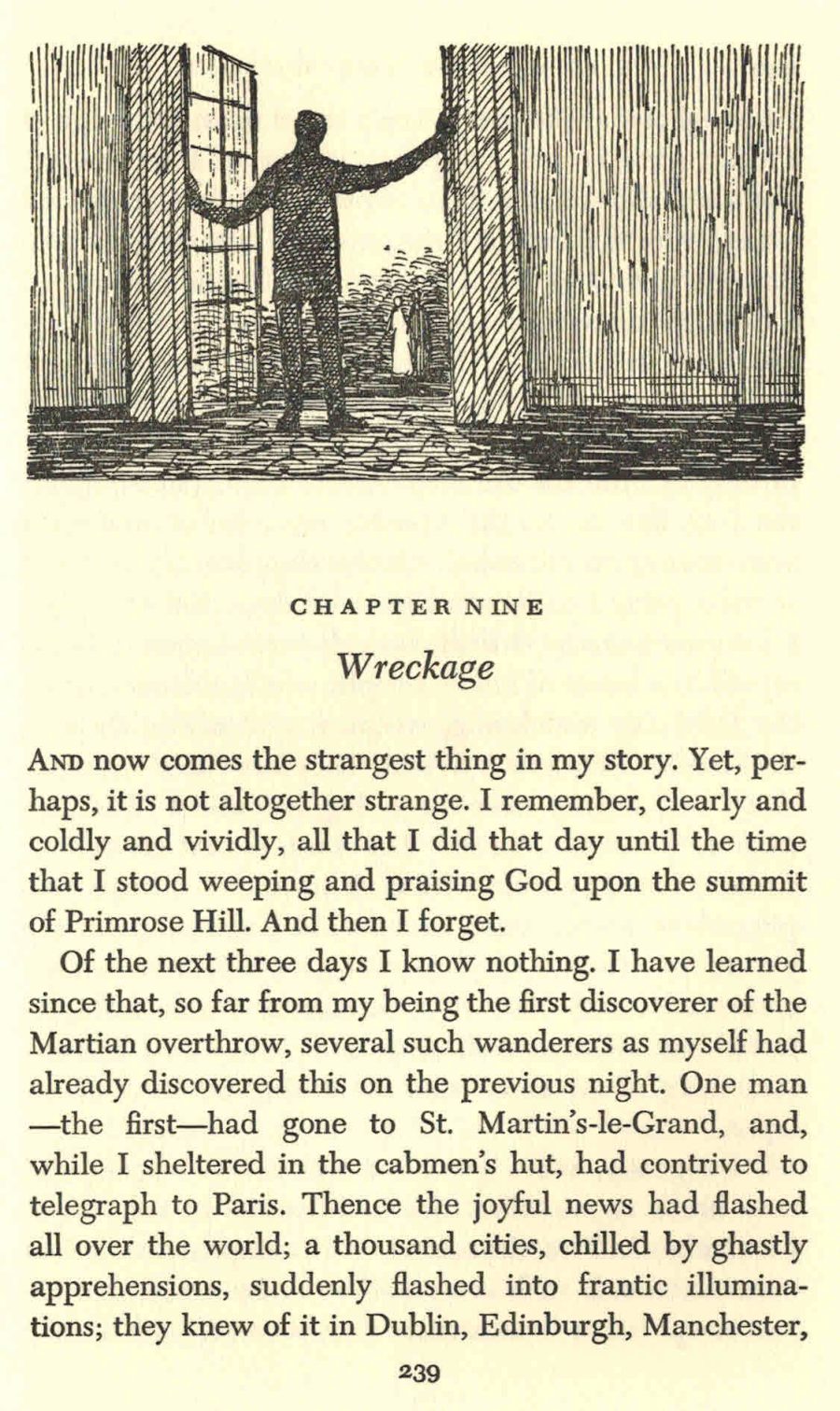

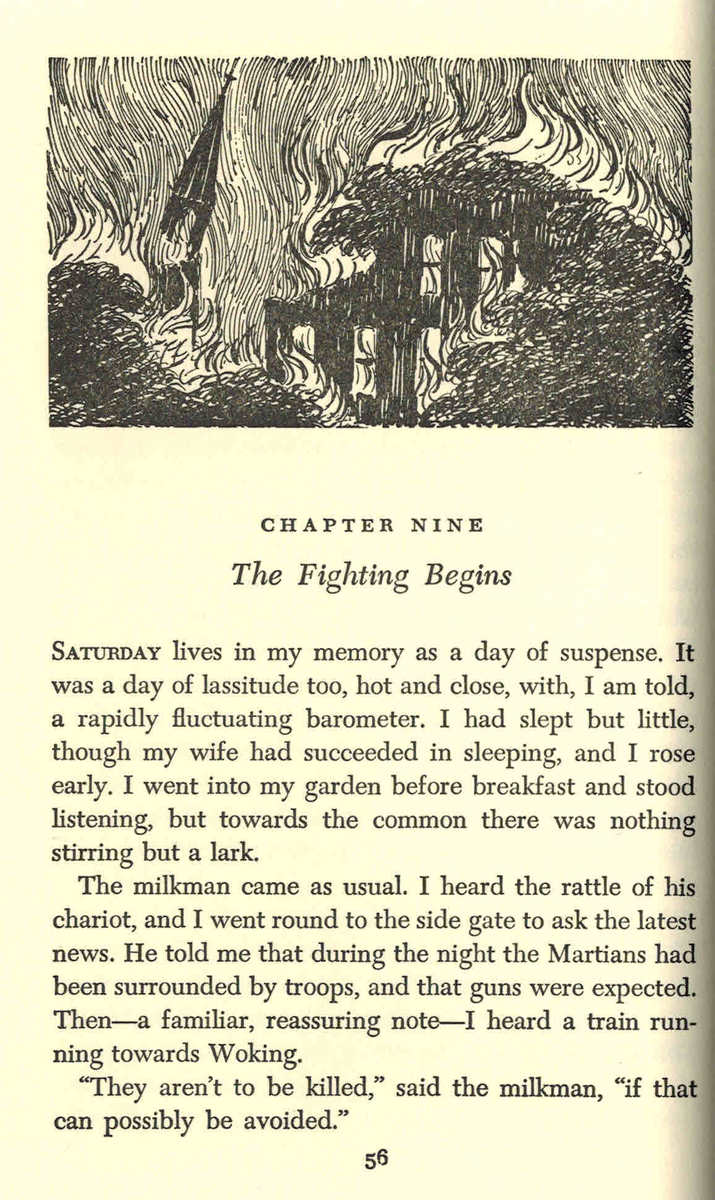

| 7:00p | Edward Gorey Illustrates H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds in His Inimitable Gothic Style (1960)  The story of malicious space aliens invading Earth has a resonance that knows no national boundaries. In fact, many modern versions make explicit the moral that only fighting off an existential threat from another planet could unify the inherently fractious human species. H.G. Wells’ 1898 novel The War of the Worlds, in many ways the archetypal telling of the space-invaders tale, certainly proved compelling on both sides of the pond: though set in Wells’ homeland of England, it made a lasting impact on American culture when Orson Welles produced a thoroughly localized version for radio, his infamous War of the Worlds Halloween 1938 broadcast. (Listen to it here.)  And so who better to illustrate a mid-2oth-century edition of the novel than Edward Gorey? He was born in and spent nearly all his life in America, but developed an artistic sensibility that struck its many appreciators as uncannily mid-Atlantic. His work continues to draw descriptions like “Victorian” and “gothic,” surely underscored by his association with the British literature-adapting television show Mystery!, for whose title sequences he drew characters and settings, and the young-adult gothic mystery novels of Anglophile author John Bellairs. The Gorey-illustrated War of the Worlds came out in 1960 from Looking Glass Library, featuring his drawings not just at the top of each chapter but on its wraparound cover as well. Though out of print, you can find old copies for sale online.  Gorey had begun his career in the early 1950s at the art department of publisher Doubleday Anchor, creating book covers and occasionally interior illustrations. In addition to Bellairs’ novels, he would also go on to put his artistic stamp on such literary classics as Bram Stoker’s Dracula and T.S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, bringing to each his signature combination of whimsy and dread in just the right proportions. Given the inherent ominousness and threat of The War of the Worlds, Gorey’s dark side comes to the fore as the story’s long-legged terrors arrive and wreak havoc on Earth, only to fall victim to common disease.  Gorey’s War of the Worlds illustrations also seem to draw some inspiration from the very first ones that accompanied the novel upon its initial publication as a Pearson’s Magazine serial in 1897. You can compare and contrast them by browsing the high-resolution scans of the out-of-print 1960 Looking Glass Library War of the Worlds at this online exhibition at Loyola University Chicago Digital Special Collections, in partnership with the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.  Though conceptually similar to the illustrations in Pearson‘s, drawn by an artist (usually of children’s books) named Warwick Goble, they don’t get into quite as much detail — but then, they don’t have to. To evoke a complex mixture of fascinated anticipation and creeping fear, Gorey never needed more than an old house, a huddle of silhouettes, or a pair of eyes glowing in the darkness. via Heavy Metal Related Content: The Very First Illustrations of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1897) Hear Orson Welles’ Iconic War of the Worlds Broadcast (1938) The Great Leonard Nimoy Reads H.G. Wells’ Seminal Sci-Fi Novel The War of the Worlds Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Edward Gorey Illustrates H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds in His Inimitable Gothic Style (1960) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

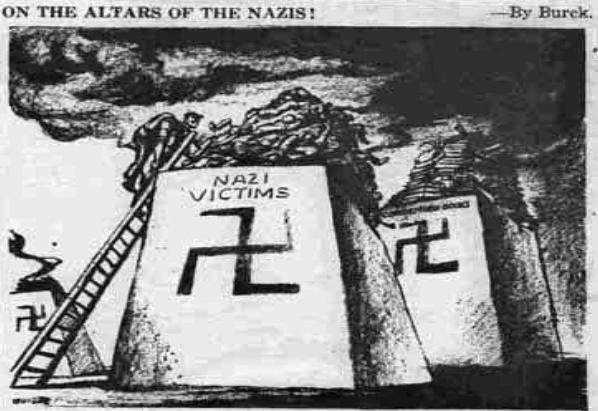

| 7:15p | Helen Keller Writes a Letter to Nazi Students Before They Burn Her Book: “History Has Taught You Nothing If You Think You Can Kill Ideas” (1933)  Helen Keller achieved notoriety not only as an individual success story, but also as a prolific essayist, activist, and fierce advocate for poor and marginalized people. She “was a lifelong radical,” writes Peter Dreier at Yes! magazine, whose “investigation into the causes of blindness” eventually led her to “embrace socialism, feminism, and pacifism.” Keller supported the NAACP and ACLU, and protested strongly against patronizing calls for her to “confine my activities to social service and the blind.” Her critics, she wrote, mischaracterized her ideas as “a Utopian dream, and one who seriously contemplates its realization indeed must be deaf, dumb, and blind.” Twenty years later she found a different set of readers treating her ideas with contempt. This time, however, the critics were in Nazi Germany, and instead of simply disagreeing with her, they added her collection of essays, How I Became a Socialist, to a list of “degenerate” books to be burned on May 10, 1933. Such was the date chosen by Hitler for “a nationwide ‘Action Against the Un-German Spirit,’” writes Rafael Medoff, to take place at German Universities—“a series of public burnings of the banned books” that “differed from the Nazis’ perspective on political, social, or cultural matters, as well as all books by Jewish authors.” Books burned included works by Einstein and Freud, H.G. Wells, Hemingway, and Jack London, Students hauled books out of the libraries as part of the spectacle. “The largest of the 34 book-burning rallies, held in Berlin,” Medoff notes, “was attended by an estimated 40,000 people.” Not only were these demonstrations of anti-Semitism, but their contempt for ideas appealed broadly to the Nazi philosophy of “Blood and Soil,” a nationalist caricature of rural values over a supposedly “degenerate,” polyglot urbanism. “The soul of the German people can again express itself,” declared Joseph Goebbels ominously at the Berlin rally. “These flames not only illuminate the final end of an old era; they also light up the new.”

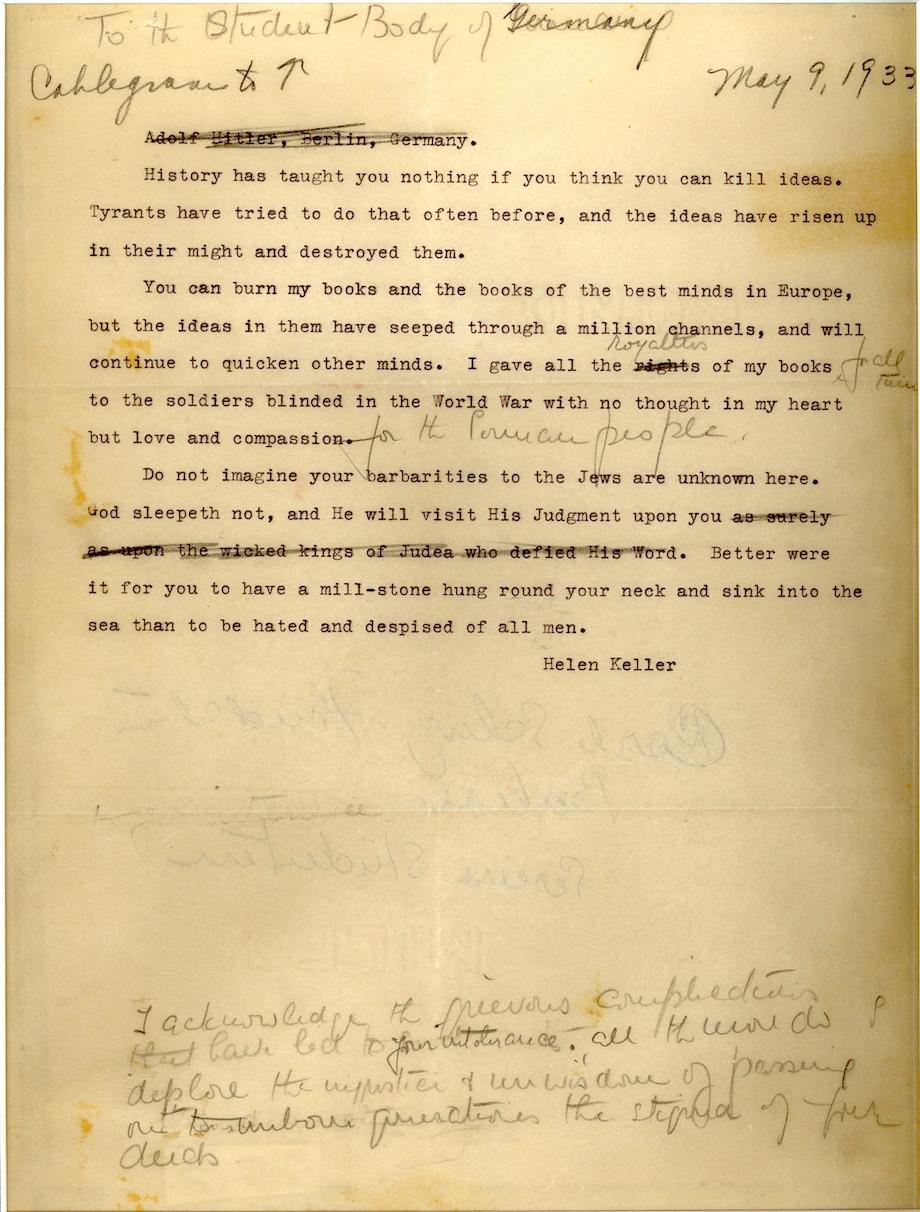

“Some American editorial responses” before and after the burnings, “made light of the event,” remarks the United States Holocaust Museum, calling it “silly” and “infantile.” Others foresaw much worse to come. In one very explicit expression of the terrible possibilities, artist and political cartoonist Jacob Burck drew the image above, evoking the observation of 19th century German writer Heinrich Heine: “Where one burns books, one will soon burn people.” Newsweek described the events as “’a holocaust of books’… one of the first instances in which the term ‘holocaust’ (an ancient Greek word meaning a burnt offering to a deity) was used in connection with the Nazis.” The day before the burnings, Keller also displayed a keen sense for the gravity of book burnings, as well as a “notable… early concern,” notes Rebecca Onion at Slate—outside the Jewish community, that is—for what she called the “barbarities to the Jews.” On May 9, 1933, Keller published a short but pointed open letter to the Nazi students in The New York Times and elsewhere, abjuring them to stop the proposed burnings. She wrote in a religious idiom, invoking the “judgment” of God and paraphrasing the Bible. (Not a traditional Christian, she belonged to a mystical sect called Swedenborgianism.) At the top of the post, you can see the typescript of her letter, with corrections and annotations by Polly Thompson, one of her primary aides. Read the full transcript below:

Keller added the penultimate paragraph of the published text later. (See the handwritten addition at the bottom of the typed draft.) Her concern for the “grievous complications” of the German people was certainly genuine. The expression also seems like a targeted rhetorical move for a student audience, conceding the situation as “complex,” and appealing in more philosophical language to “justice” and “wisdom.” The Nazis ignored her protest, as they did the “massive street demonstrations” that took place on the 10th “in dozens of American cities,” the Holocaust Museum writes, “skillfully organized by the American Jewish Congress” and sparking “the largest demonstration in New York City history up to that date.” Five years later, however, another planned book burning—this time in Austria before its annexation—was prevented by students at Williams College, Yale, and other universities in the U.S., where pro- and anti-Nazi partisans fought each other on several American campuses. U.S. students were able to push the Austrian National Library to lock the books away rather than burn them. Keller “is not known to have commented specifically” on these student protests, writes Medoff, “but one may assume she was deeply proud that at a time when too many Americans did not want to be bothered with Europe’s problems, these young men and women understood the message of her 1933 letter—that the principles under attack by the Nazis were something that should matter to all mankind.” via Slate Related Content: Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Helen Keller Writes a Letter to Nazi Students Before They Burn Her Book: “History Has Taught You Nothing If You Think You Can Kill Ideas” (1933) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/05/16 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |