[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, May 26th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | An Animated History of Tea Self proclaimed tea geek, Shunan Teng’s knowledge of her chosen subject extends well beyond the proper way to serve and prepare her best-loved beverage. Her recent TED-Ed lesson on the History of Tea, above, hints at centuries of bloodshed and mercenary trade practices, discreetly masked by Steff Lee’s benign animation. Addiction, war, and child labor—the last, a grim ongoing reality…. Meditate on that the next time you’re enjoying a nice cup of Darjeeling, or better yet, matcha, a preparation whose Western buzz is starting to approximate that of the Tang dynasty. Even die-hard coffee loyalists with little patience for the ritualistic niceties of tea culture can indulge in some fascinating trivia, from the invention of the clipper ship to the possible health benefits of eating rather than drinking those green leaves. Test your TQ post-lesson with TED-Ed’s quiz, or this one from Tea Drunk, Teng’s authentic Manhattan tea house. Related Content: George Orwell Explains How to Make a Proper Cup of Tea 10 Golden Rules for Making the Perfect Cup of Tea (1941) “The Virtues of Coffee” Explained in 1690 Ad: The Cure for Lethargy, Scurvy, Dropsy, Gout & More Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She’ll be appearing onstage in New York City this June as one of the clowns in Paul David Young’s Faust 3. Follow her @AyunHalliday. An Animated History of Tea is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 1:30p | Watch a Mesmerizing Hourglass Filled with 1,250,000 “Nanoballs” (Created by the Designer of the Apple Watch)

Apple Watch designer Marc Newson has created an hourglass that stands about 6 inches tall, measures 5 inches wide, and features 1,249,996 tiny spheres called “nanoballs,” each made of stainless steel and covered with a fine copper coating. It takes 10 minutes for the nanoballs to pour through the glass, from first to last. The action looks pretty mesmerizing, to say the least. You can pick up your very own hand-made hourglass for $12,000. But if your pockets don’t run quite that deep, you can settle for watching the time piece in the video above. Get more information on the Newson hourglass here. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you’d like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: Why Time Seems to Speed Up as We Get Older: What the Research Says How Clocks Changed Humanity Forever, Making Us Masters and Slaves of Time Watch a Mesmerizing Hourglass Filled with 1,250,000 “Nanoballs” (Created by the Designer of the Apple Watch) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

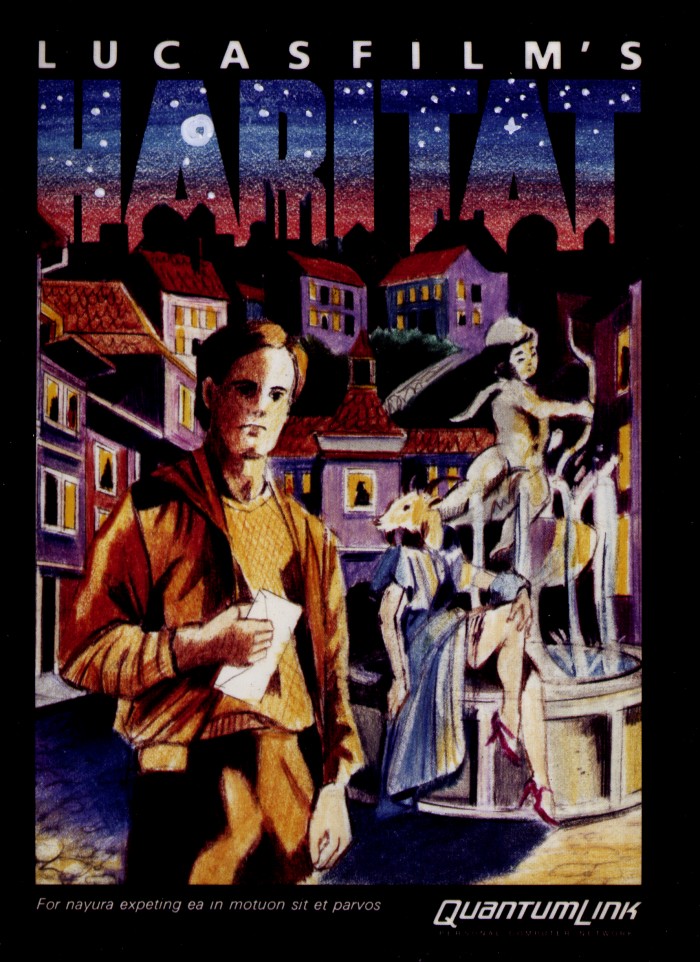

| 3:00p | The Story of Habitat, the Very First Large-Scale Online Role-Playing Game (1986) Long before World of Warcraft, before Everquest and Second Life, and even before Ultima Online, computer-gamers of the 1980s looking for an online world to explore with others of their kind could fire up their Commodore 64s, switch on their dial-up modems, and log into Habitat. Brought out for the Commodore online service Quantum Link by Lucasfilm Games (later known as the developer of such classic point-and-click adventure games as Maniac Mansion and The Secret of Monkey Island, now known as Lucasarts), Habitat debuted as the very first large-scale graphical virtual community, blazing a trail for all the massively multiplayer online role-playing games (or MMORPGs) so many of us spend so much of our time playing today. Designed, in the words of creators Chip Morningstar and F. Randall Farmer, to “support a population of thousands of users in a single shared cyberspace,” Habitat presented “a real-time animated view into an online simulated world in which users can communicate, play games, go on adventures, fall in love, get married, get divorced, start businesses, found religions, wage wars, protest against them, and experiment with self-government.” All that happened and more within the service’s virtual reality during its pilot run from 1986 to 1988. The features both cautiously and recklessly implemented by Habitat‘s developers, and the feedback they received from its users, laid down the template for all the more advanced graphical online worlds to come. At the top of the post, you can watch Lucasfilm’s original Habitat promotional video promise a “strange new world where names can change as quickly as events, surprises lurk at every turn, and the keynotes of existence are fantasy and fun,” one where “thousands of avatars, each controlled by a different human, can converge to shape an imaginary society.” (All performed, the narrator notes, “with the cooperation of a huge mainframe computer in Virginia.”) The form this society eventually took impressed Habitat‘s creators as much as anyone, as Farmer writes in his “Habitat Anecdotes” from 1988, an examination of the most memorable happenings and phenomena among its users.  Farmer found he could group those users into five now-familiar categories: the Passives (who “want to ‘be entertained’ with no effort, like watching TV”), the Active (whose “biggest problem is overspending”), the Motivators (the most valuable users, for they “understand that Habitat is what they make of it”), the Caretakers (employees who “help the new users, control personal conflicts, record bugs” and so on), and the Geek Gods (the virtual world’s all-powerful administrators). Sometimes everyone got along smoothly, and sometimes — inevitably, given that everyone had to define the properties of this brand new medium even as they experienced it — they didn’t. “At first, during early testing, we found out that people were taking stuff out of others’ hands and shooting people in their own homes,” Farmer writes. Later, a Greek Orthodox Minister opened Habitat‘s first church, but “I had to eventually put a lock on the Church’s front door because every time he decorated (with flowers), someone would steal and pawn them while he was not logged in!” This citizen-governed virtual society eventually elected a sheriff from among its users, though the designers could never quite decide what powers to grant him. Other surprisingly “real world” institutions developed, including a newspaper whose user-publisher “tirelessly spent 20-40 hours a week composing a 20, 30, 40 or even 50 page tabloid containing the latest news, events, rumors, and even fictional articles.” Though developing this then-advanced software for “the ludicrous Commodore 64” posed a serious technical challenge, write Farmer and Morningstar in their 1990 paper “The Lessons of Lucasfilm’s Habitat,” the real work began when the users logged on. All the avatars needed houses, “organized into towns and cities with associated traffic arteries and shopping and recreational areas” with “wilderness areas between the towns so that everyone would not be jammed together into the same place.” Most of all, they needed interesting places to visit, “and since they can’t all be in the same place at the same time, they needed a lot of interesting places to visit. [ … ] Each of those houses, towns, roads, shops, forests, theaters, arenas, and other places is a distinct entity that someone needs to design and create. Attempting to play the role of omniscient central planners, we were swamped.” All this, the creators discovered, required them to stop thinking like the engineers and game designers they were, giving up all hope of rigorous central planning and world-building in favor of figuring out the tricker problem of how, “like the cruise director on an ocean voyage,” to make Habitat fun for everyone. Farmer faces that question again today, having launched the open-source NeoHabitat project earlier this year with the aim of reviving the Habitat world for the 21st century. As much progress as graphical multiplayer online games have made in the past thirty years, the conclusion Farmer and Morningstar reached after their experience creating the first one holds as true as ever: “Cyberspace may indeed change humanity, but only if it begins with humanity as it really is.” Related Content: Free: Play 2,400 Vintage Computer Games in Your Web Browser Long Live Glitch! The Art & Code from the Game Now Released into the Public Domain Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Story of Habitat, the Very First Large-Scale Online Role-Playing Game (1986) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:10p | Timelapse Animation Lets You See the Rise of Cities Across the Globe, from 3700 BC to 2000 AD Last year, a Yale-led research project produced an innovative dataset that mapped the history of urban settlements. Covering a 6,000 year period, the project traced the location and size of cities across the world, starting in 3700 BC (when the first known urban dwellings emerged in Sumer) and continuing through 2000 AD. According to Yale’s Meredith Reba, if we understand “how cities have grown and changed over time, throughout history, it might tell us something useful about how they are changing today,” and particularly whether we can find ways to make modern cities sustainable. The Yale dataset was originally published in Scientific Data in 2016. And before too long, some enterprising YouTuber brought the data to life. Above, the history of urban life unfolds before your eyes. The action starts off slow, but then later kicks into high gear. You can read more about the mapping of urban settlements at this Yale website. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you’d like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content The Rise & Fall of the Romans: Every Year Shown in a Timelapse Map Animation (753 BC -1479 AD) 200,000 Years of Staggering Human Population Growth Shown in an Animated Map Timelapse Animation Lets You See the Rise of Cities Across the Globe, from 3700 BC to 2000 AD is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00p | How Finland Created One of the Best Educational Systems in the World (by Doing the Opposite of U.S.) Every conversation about education in the U.S. takes place in a minefield. Unless you’re a billionaire who bought the job of Secretary of Education, you’d better be prepared to answer questions about racial and economic equity, disability issues, protections for LGBTQ students, teacher pay and unions, religious charter schools, and many other pressing concerns. These issues are not mutually exclusive, nor are they distinct from questions of curriculum, testing, or achievement. The terrain is littered with possible explosive conflicts between educators, parents, administrators, legislators, activists, and profiteers. The needs of the most deeply invested stakeholders, as they say, the students themselves, seem to get far too little consideration. What if we in the U.S., all of us, actually wanted to improve the educational experiences and academic outcomes for our children—all of them? Where might we look for a model? Many people have looked to Finland, at least since 2010, when the documentary Waiting for Superman contrasted struggling U.S. public schools with highly successful Finnish equivalents. The film, a positive spin on the charter school movement, received significant backlash for its cherry-picked examples and blaming of teachers’ unions for America’s failing schools. By contrast, Finland’s schools have been described by William Doyle, an American Fulbright Scholar who studies them, as “the ‘ultimate charter school network'” (a phrase, we’ll see, that means little in the Finnish context.) There, Doyle writes at The Hechinger Report, “teachers are not strait-jacketed by bureaucrats, scripts or excessive regulations, but have the freedom to innovate and experiment as teams of trusted professionals.” Last year, Michael Moore featured many of Finland’s innovative educational experiments in his humorous, hopeful travelogue Where to Invade Next. In the clip above, you can hear from the country’s Minister of Education, Krista Kiuru, who explains to him why Finnish children do not have homework; hear also from a group of high school students, high school principal Pasi Majassari, first grade teacher Anna Hart and many others. Shorter school hours—the “shortest school days and shortest school years in the entire Western world”—leave plenty of time for leisure and recreation. Kids bake, hike, build things, make art, conduct experiments, sing, and generally enjoy themselves. “There are no mandated standardized tests,” writes LynNell Hancock at Smithsonian, “apart from one exam at the end of students’ senior year in high school… there are no rankings, no comparisons or competition between students, schools or regions.” Yet Finnish students have, in the past several years, consistently ranked in the top ten among millions of students worldwide in science, reading, and math. “If there was one thing I kept hearing over and over again from the Finns,” says Moore above, “it’s that America should get rid of standardized tests,” should stop teaching to those tests, stop designing entire curricula around multiple-choice tests. Hancock describes the results of the Finnish system, and its costs:

Moore’s camera registers the shock on Finnish educators’ faces when they hear that many U.S. schools eliminated music, art, poetry and other pursuits in order to focus almost exclusively on testing. Though lighthearted in tone, the segment really drives home the depressing degree to which so many U.S. students receive an impoverished education—one barely worthy of the name—unless they luck into a voucher for a high-end charter school or have the independent means for an expensive private one. In Finland, says the Minister of Education, “all the schools are equal. You never ask where the best school is.” It’s also illegal in Finland to profit from schooling. Wealthy parents have to ensure that neighborhood schools can give their kids the best education possible, because they are the only option. Many people in the U.S. object to comparisons like Moore’s by noting that societies like Finland are “homogenous” next to what may seem to them like maddening cultural diversity in the U.S. However, Finland has incorporated (not without difficulty) large immigrant and refugee populations—even as its schools continue to improve. The government has responded in part to rising immigration with educational solutions such as this one, a “national initiative to reinforce Finnish higher education institutions (HEIs) as significant stakeholders in migrants’ integration.” The subtantive differences between the two countries’ educational systems may have less to do with demography and more to do with economics and the training and social status of teachers. In Finland, writes Doyle, no teacher “is allowed to lead a primary school class without a master’s degree in education, with specialization in research and classroom practice.” Teaching “is the most admired job in Finland next to medical doctors.” And as Dana Goldstein points out at The Nation—a fact Waiting for Superman failed to mention—Finnish teachers are “gasp!—unionized and granted tenure.” Perhaps an even more significant difference the documentary glossed over: in Finland, “families benefit from a cradle-to-grave social welfare system that includes universal daycare, preschool and healthcare, all of which are proven to help children achieve better results at school.” Hundreds of studies in recent years substantiate this claim. It would seem intuitive that stresses associated with hunger and poverty would have a pernicious effect on learning, especially when poorer schools are so egregiously under-resourced. And the data says as much, to varying degrees. And yet, we are now in the U.S. slashing breakfast and lunch programs that feed hungry children and deciding whether to uninsure millions of families as millions more still lack basic health coverage. Most every American parent knows that quality daycares and preschools can cost as much per year as a decent university education in this country. It seems to many of us that the atrocious state of the U.S. educational system can only be attributed to an act of will on the part our political elite, who see schools as competition for fundamentalist belief systems, opportunities to punish their opponents out of spite, or as rich fields for private profit. But it needn’t be so. It took 40 years for the Finns to create their current system. In the 1960s, their schools ranked on the very low end—along with those in the U.S. By most accounts, they’ve since shown there can be systems that, while surely imperfect in their own way, work for all kids, embedded within larger systems that prize their teachers and families. Related Content: In Japanese Schools, Lunch Is As Much About Learning As It’s About Eating Meditation is Replacing Detention in Baltimore’s Public Schools, and the Students Are Thriving Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Finland Created One of the Best Educational Systems in the World (by Doing the Opposite of U.S.) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/05/26 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |