[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, June 5th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 8:23a | A New Theme Park Celebrating Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro Set to Open in 2020

Is a frame of reference necessary to appreciate Disney World? Can you enjoy a ride in a spinning teacup if you have no working knowledge of Alice in Wonderland? What sort of magic might the Magic Kingdom hold for those who’ve never heard of Cinderella or Peter Pan? Now imagine if the theme park’s scope was narrowed to a single film. You’ve got until 2020 to sneak in a viewing of the Hayao Miyazaki film, My Neighbor Totoro, before Ghibli Park, a 500-acre amusement park on the grounds of Japan's 2005 World’s Fair site, opens. To date, Miyazaki's Studio Ghibli has produced more than a dozen feature-length animated films. That’s a lot of raw material for attractions. Porco Rosso’s 1930s seaplanes have ride written all over them, and think of the Haunted Mansion-esque thrills that could be wrung from Spirited Away’s bathhouse. How about a Jungle Cruise-style ramble through the countryside in Howl's Moving Castle? An underwater adventure with goldfish princess Ponyo? Prepare for a very long wait if you’re joining the queue for those. It’s being reported that Ghibli Park will focus exclusively on a single film, 1988’s My Neighbor Totoro. (Care to take a guess what its Mouse Ears will look like?) The film’s theme of respect for the natural world is good news for the area’s existing flora. The governor of Japan's Aichi Prefecture, where Ghibli Park is to be situated, has announced that it will be laid out in such a way as to preserve the trees. Presumably the film’s iconic cat bus and fast growing camphor tree, above, will be powered by the greenest of energies. Preview the sort of wonders in store by touring the lifesize house of My Neighbor Totoro's human characters, Satsuki and Mei, below. Related Content: Hayao Miyazaki’s Masterpieces Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke Imagined as 8-Bit Video Games Software Used by Hayao Miyazaki’s Animation Studio Becomes Open Source & Free to Download Hayao Miyazaki Picks His 50 Favorite Children’s Books Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She’ll be appearing onstage in New York City in Paul David Young’s Faust 3, opening later this week. Follow her @AyunHalliday. A New Theme Park Celebrating Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro Set to Open in 2020 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

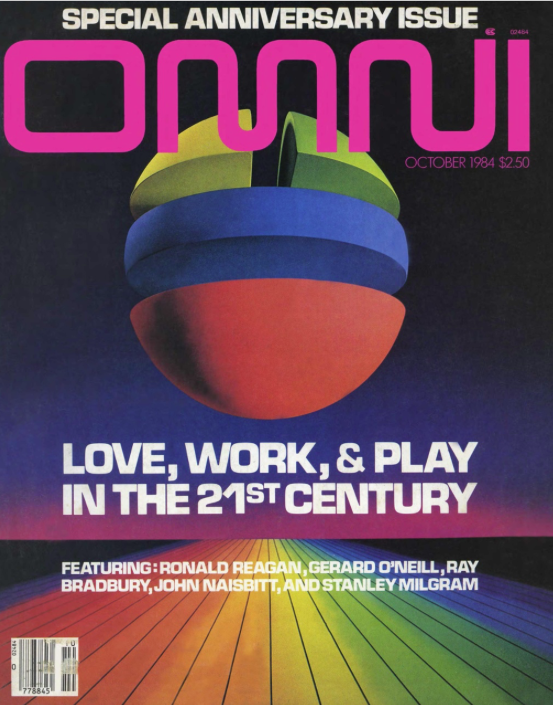

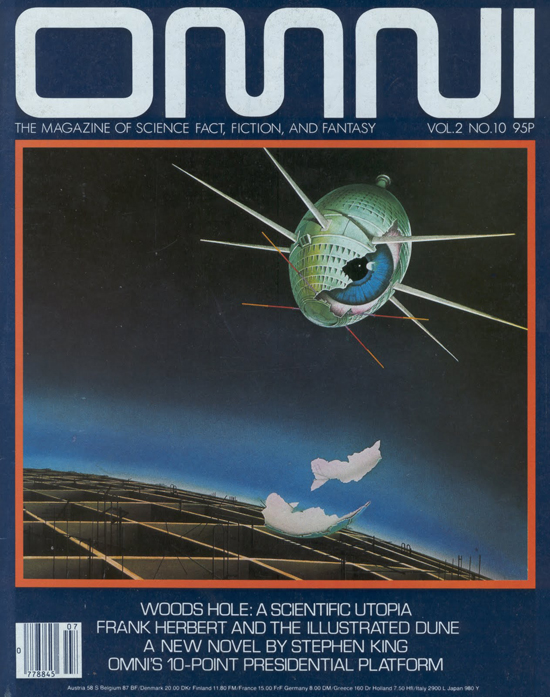

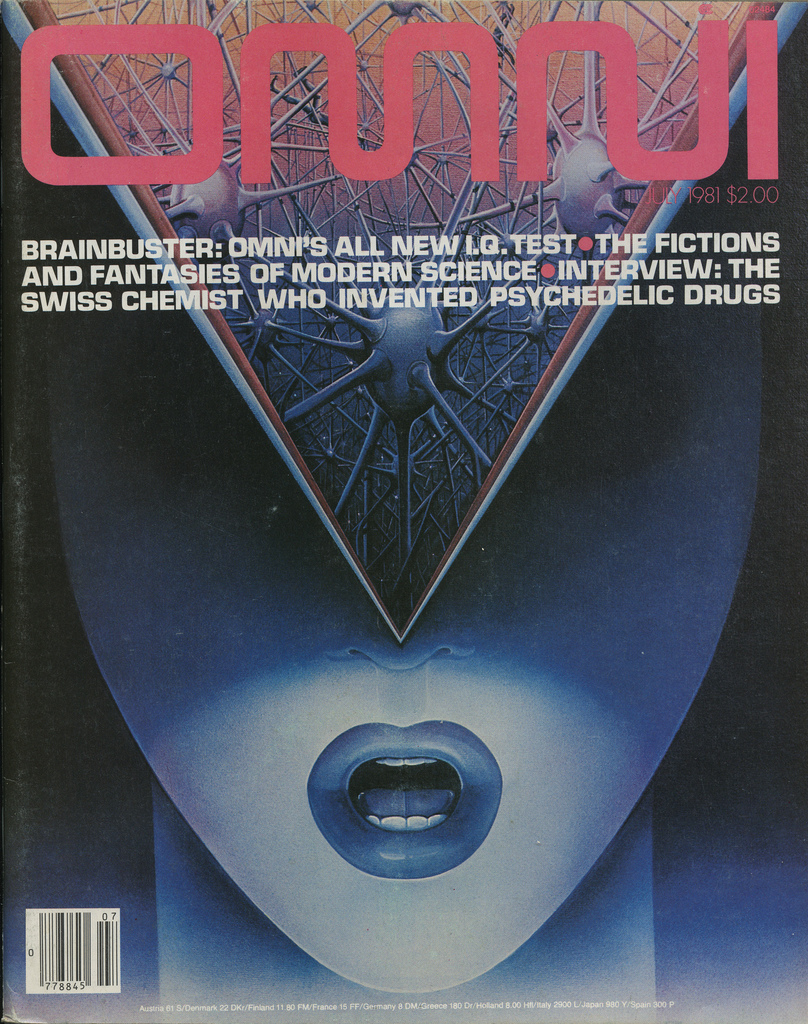

| 2:30p | Omni, the Iconic Sci-Fi Magazine, Now Digitized in High-Resolution and Available Online There was a time, not so long ago, when not only could a blockbuster Hollywood comedy make a reference to a science magazine, but everyone in the audience would get that reference. It happened in Ghostbusters, right after the titular boys in gray hit it big with their first high-profile busting of a ghost. In true 1980s style, a success montage followed, in the middle of which appeared the cover of Omni magazine's October 1984 issue which, according to the Ghostbusters Wiki, "featured a Proton Pack and Particle Thrower. The tagline read, 'Quantum Leaps: Ghostbusters' Tools of the Trade.'"  The movie made up that cover, but it didn't make up the publication. In reality, the cover of Omni's October 1984 issue, a special anniversary edition which appears at the top of the magazine's Wikipedia page today, promised predictions of "Love, Work & Play in the 21st Century" from the likes of beloved sci-fi writer Ray Bradbury, social psychologist Stanley Milgram, physicist Gerard O'Neill, trend-watcher John Naisbitt — and, of course, Ronald Reagan. Now you can find that issue of Omni, as well as every other from its 1978-to-1995 run, digitized in high-resolution and made available on Amazon. "Omni was a magazine about the future," writes Motherboard's Claire Evans, telling the story of "the best science magazine that ever was." In its heyday, it blew minds by regularly featuring extensive Q&As with some of the top scientists of the 20th century–E.O. Wilson, Francis Crick, Jonas Salk–tales of the paranormal, and some of the most important science fiction to ever see magazine publication" by William Gibson, Orson Scott Card, Harlan Ellison, George R. R. Martin — and even the likes of Stephen King, Joyce Carol Oates, and William S. Burroughs. "By coupling science fiction and cutting-edge science news, the magazine created an atmosphere of possibility, where even the most outrageous ideas seemed to have basis in fact."  Originally founded by Kathy Keeton (formerly, according to Evans, "a South African ballerina who went from being one of the highest-paid strippers in Europe") and Penthouse publisher Bob Guccione, Omni not only had an impact in unexpected areas (the eccentric musical performer Klaus Nomi, himself a cultural innovator, took his name in part from the magazine's) but took steps into the digital realm long before other print publications dared. It first established its online presence on Compuserve in 1986; seven years later, it opened up its archives, along with forums and new content, on America Online, a first for any major magazine. Now Amazon users can purchase Omni's digital back issues for $2.99 each, or read them for free if they have Kindle Unlimited accounts. (You can sign up for a 30-day free trial for Kindle Unlimited and start binge-reading Omni here.)  Jerrick Media, owners of the Omni brand, have also begun to make available on Vimeo on Demand episodes of Omni: The New Frontier, the 1980s syndicated television series hosted by Peter Ustinov. And without paying a dime, you can still browse the fascinating Omni material archived at Omni Magazine Online, an easy way to get a hit of the past's idea of the future — and one presenting, in the words of 1990s editor-in-chief Keith Farrell, "a fascination with science and speculation, literature and art, philosophy and quirkiness, serious speculation and gonzo speculation, the health of the planet and its cultures, our relationship to the universe and its (possible) cultures, and a sense that whatever else, tomorrow would be different from today." Related Content: Spy Magazine (1986-1998) Now Online A Complete Digitization of Eros Magazine: The Controversial 1960s Magazine on the Sexual Revolution Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Omni, the Iconic Sci-Fi Magazine, Now Digitized in High-Resolution and Available Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:27p | Bob Dylan Potato Chips, Anyone?: What They’re Snacking on in China  They sound tasty. The rub? You have to travel to China to get them. And now a question for any readers fluent in Chinese. Can you translate the text on the bag? We would be curious to know what's the pitch for these chips. Feel free to put any translations in comments section below. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: Allen Ginsberg Teaches You How to Meditate with a Rock Song Featuring Bob Dylan on Bass Two Legends Together: A Young Bob Dylan Talks and Plays on The Studs Terkel Program, 1963 Jeff Bridges Narrates a Brief History of Bob Dylan’s and The Band's Basement Tapes Bob Dylan Potato Chips, Anyone?: What They’re Snacking on in China is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:15p | Hunter S. Thompson Typed Out The Great Gatsby & A Farewell to Arms Word for Word: A Method for Learning How to Write Like the Masters  The word quixotic derives, of course, from Miguel Cervantes’ irreverent early 17th century satire, Don Quixote. From the novel’s eponymous character it carries connotations of antiquated, extravagant chivalry. But in modern usage, quixotic usually means “foolishly impractical, marked by rash lofty romantic ideas.” Such designations apply in the case of Jorge Luis Borges’ story, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” in which the titular academic writes his own Quixote by recreating Cervantes’ novel word-for-word. Why does this fictional minor critic do such a thing? Borges’ explanations are as circuitously mysterious as you might expect. But we can get a much more straightforward answer from a modern-day Quixote—an individual who has undertaken many a “foolishly impractical” quest: Hunter S. Thompson. Though he would never be mistaken for a knight-errant, Thompson did tilt at more than a few windmills, including Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, from which he typed whole pages, word-for-word “just to get the feeling,” writes Louis Menand at The New Yorker, “of what it was like to write that way.” “You know Hunter typed The Great Gatsby,” an awestruck Johnny Depp told The Guardian in 2011, after he’d played Thompson himself in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and a fictionalized version of him in an adaptation of Thompson’s lost novel The Rum Diaries. “He’d look at each page Fitzgerald wrote, and he copied it. The entire book. And more than once. Because he wanted to know what it felt like to write a masterpiece.” This exercise prepared him to write one, or his cracked version of one, 1972’s gonzo account of a more-than-quixotic road trip, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Menand points out that Thompson first called the book The Death of the American Dream, likely inspired by Fitzgerald’s first Gatsby title, The Death of the Red White and Blue. Thompson referred to Gatsby frequently in books and letters. Just as often, he referenced another literary hero—and pugnacious Fitzgerald competitor—Ernest Hemingway. He first began typing out Gatsby while employed at Time magazine as a copy boy in 1958, one of many magazine and newspaper jobs in a “pattern of disruptive employment,” writes biographer Kevin T. McEneaney. “Thompson appropriated armloads of office supplies” for the task, and also typed out Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms and “some of Faulkner’s stories—an unusual method for learning prose rhythm.” He was fired the following year, not for misappropriation, but for “his unpardonable, insulting wit at a Christmas party.” In a 1958 letter to his hometown girlfriend Ann Frick, Thompson named the Fitzgerald and Hemingway novels as two especially influential books, along with Brave New World, William Whyte’s The Organization Man, and Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything (or “Girls before Girls”), a novel that “hardly belongs in the abovementioned company,” he wrote, and which he did not, presumably, copy out on his typewriter at work. Surely, however, many a Thompson close reader has discerned the traces of Fitzgerald, Faulkner, and Hemingway in his work, particularly the latter, whose macho escapades and epic drinking bouts surely inspired more than just Thompson’s writing. In Borges’ “Pierre Menard,” the title character first sets out to “be Miguel de Cervantes”—to “Learn Spanish, return to Catholicism, fight against the Moor or Turk, forget the history of Europe from 1602 to 1918….” He finds the undertaking not only “impossible from the outset,” but also “the least interesting” way to go about writing his own Quixote. Thompson may have discovered the same as he worked his way through his influences. He could not become his heroes. He would have to take what he’d learned from inhabiting their prose, and use it as fuel for his literary firebombs–or, seen differently, for his idealistic, impractical, yet strangely noble (in their way) knight's quests. Not since Thompson's Nixonian heyday has there been such need for a ferocious outlaw voice like his. He may have become a stock character by the end of his life, caricatured as Uncle Duke in Doonesbury, given pop culture sainthood by Depp's unhinged portrayal. But "at its best," writes Menand, "Thompson's anger, in writing, was a beautiful thing, fearless and funny and, after all, not wrong about the shabbiness and hypocrisy of American officialdom." Perhaps even now, some hungry young intern is typing out Fear and Loathing word-for-word, preparing to absorb it into his or her own 21st century repertoire of barbed-wire truth-telling about “the death of the American dream.” The method, it seems, may work with any great writer, be it Cervantes, Fitzgerald, or Hunter S. Thompson. Related Content: Read 18 Lost Stories From Hunter S. Thompson’s Forgotten Stint As a Foreign Correspondent Hunter S. Thompson, Existentialist Life Coach, Gives Tips for Finding Meaning in Life Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Hunter S. Thompson Typed Out The Great Gatsby & A Farewell to Arms Word for Word: A Method for Learning How to Write Like the Masters is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/06/05 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |