[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, June 8th, 2017

| Time | Event |

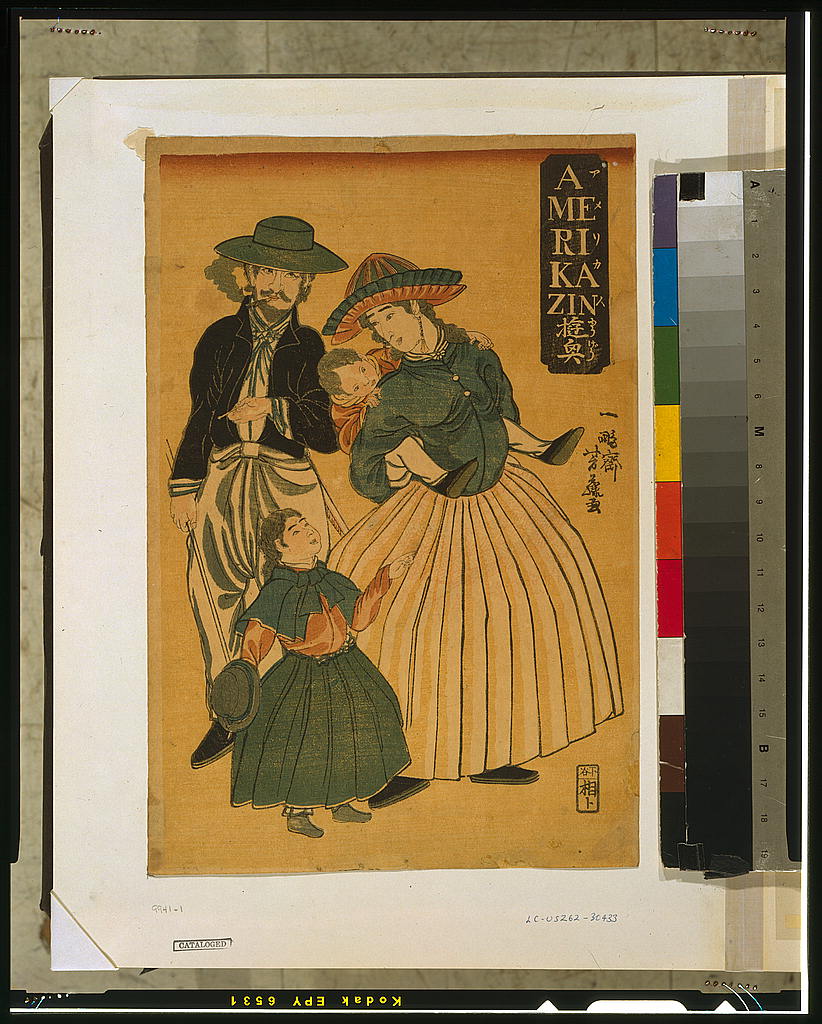

| 8:00a | Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600-1915)  No one art form has done more to shape the world's sense of traditional Japanese aesthetics than the woodblock print. But not so very long ago, in historical terms, no such works had ever left Japan. That changed when, according to the Library of Congress, "American naval officer Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858) led an expedition to Japan between 1852 and 1854 that was instrumental in opening Japan to the Western world after more than 200 years of national seclusion." As travelers, materials, and products began flowing between Japan and the West, so did art.  This flow happened, of course, by sea, and so Japanese artists working in woodblock and other forms soon found that the port city of Yokohama had become "an incubator for a new category of images that straddled convention and novelty." In their depictions of modern Yokohama, "bewhiskered men and crinoline-clad women were shown striding through the city, clambering on and off ships, riding horses, enjoying local entertainments, and interacting with an endless array of objects from goblets to locomotives." This new genre in an established tradition took on the name "Yokohama-e," or "pictures of Yokohama."  Hundreds of years earlier, during the Tokugawa Period that began in the year 1600, that tradition had already produced the now well-known genre of "Ukiyo-e," or "pictures of the floating world," woodblock depictions of the pleasure districts of Edo, now called Tokyo. "Various forms of entertainment, particularly kabuki theater and the pleasure quarters, lured monied patrons who were eager in turn to acquire the vivid images of celebrated actors and beautiful courtesans." Later, "travel became a popular form of leisure and the pleasures of the natural environment, interesting landmarks, and the adventures encountered en route also became favorite Ukiyo-e themes." Ukiyo-e also looked to "Japanese myth, legend, literature, history, and daily life" for subjects, and so its prolific artists captured the culture nearly whole.  You can come as close as possible to experiencing that culture by viewing, and downloading, more than 2,500 Japanese woodblock prints and drawings at the Library of Congress' online collection "Fine Prints: Japanese, pre-1915." It includes work from such prolific Ukiyo-e artists as Hokusai Katsushika (whose Teahouse at Koishikawa the Morning After a Snowfall appears at the top of the post), Andō Hiroshige (Minakuchi below that), Isoda Koryūsai (Kisaragi, third from the top), and Utagawa Yoshifuji (whose Amerikajin Yūgyō, one of his depictions of Americans, appears just above). As much as Japan has changed since the heyday of the Yokohama-e, much less the Ukiyo-e, any visitor to the country in the 21st century will first notice not how much the surfaces of Japan's real urban and natural landscapes, domestic interiors, and public scenes differ from those in classical woodblock prints, but how deeply they've remained the same. Enter the collection here. Related Content: Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition Splendid Hand-Scroll Illustrations of The Tale of Genjii, The First Novel Ever Written (Circa 1120) The (F)Art of War: Bawdy Japanese Art Scroll Depicts Wrenching Changes in 19th Century Japan Hayao Miyazaki’s Beloved Characters Reimagined in the Style of 19th-Century Woodblock Prints Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600-1915) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | The History of Classical Music in 1200 Tracks: From Gregorian Chant to Górecki What is classical music? It may seem like a remedial question, but it is a serious one. Leonard Bernstein took it seriously enough to design an entire program around it. His “Young People’s Concerts” with the New York Philharmonic—broadcast on TV from Carnegie Hall in 1959—began with an admission of how unclear the term's usage had become in popular culture. “You see,” he told his young audience, “everybody thinks he knows what classical music is… People use this word to describe music that isn’t jazz or popular songs or folk music, just because there isn’t any other word that seems to describe it better.” Classical music is often thought of in even more nebulous, and perhaps elitist, terms as "art music," over and above these other forms. Yet Bernstein goes on to define classical music in more precise ways: A classical composer “puts down the exact notes that he wants, the exact instruments or voices that he wants to play or sing those notes—even the exact number of instruments or voices; and he also writes down as many directions as he can think of” about tempo, dynamics, etc. What might sound like a straightjacket for musicians instead offers an interpretive challenge: "No performance can be perfectly exact.... But that's what makes the performer's job so exciting–to try and find out from what the composer did write down as exactly as possible what he meant." This working definition, while devoid of technical jargon for the sake of Bernstein's untrained audience, still manages to give us a good sense of the parameters he set for the "classical." They do not stretch widely enough to include improvisatory modernism (though he had a high regard for jazz as a separate category). But they do include much instrumental and choral European music from the start of the medieval period into the 20th century. The definition could be a much narrower one. "One of the first things you learn when you're introduced to classical music," Jay Gabler writes at online radio station Classical MPR, "is that the term 'classical' most properly describes music composed from about 1750 to 1820." [Error: Irreparable invalid markup ('<div [...] http://cdn8.openculture.com/>') in entry. Owner must fix manually. Raw contents below.] <div class="oc-video-wrapper">

<div class="oc-video-container">

<p><a href="http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gtkmnhnHWhw"><img src="http://img.youtube.com/vi/gtkmnhnHWhw/default.jpg" border="0" width="320" /></a></p>

</div>

<p> <!-- /oc-video-embed -->

</p></div>

<p><!-- /oc-video-wrapper --></p>

<p>What is classical music? It may seem like a remedial question, but it is a serious one. Leonard Bernstein took it seriously enough to design an entire program around it. His “Young People’s Concerts” with the New York Philharmonic—broadcast on TV from Carnegie Hall in 1959—<a href="https://leonardbernstein.com/lectures/television-scripts/young-peoples-concerts/what-is-classical-music">began with an admission</a> of how unclear the term's usage had become in popular culture. “You see,” he told his young audience, “everybody thinks he knows what classical music is… People use this word to describe music that isn’t jazz or popular songs or folk music, just because there isn’t any other word that seems to describe it better.”</p>

<p>Classical music is often thought of in even more nebulous, and perhaps elitist, terms as "art music," over and above these other forms. Yet Bernstein goes on to define classical music in more precise ways: A classical composer “puts down the exact notes that he wants, the exact instruments or voices that he wants to play or sing those notes—even the exact number of instruments or voices; and he also writes down as many directions as he can think of” about tempo, dynamics, etc. What might sound like a straightjacket for musicians instead offers an interpretive challenge: "No performance can be perfectly exact.... But that's what makes the performer's job so exciting–to try and find out from what the composer did write down as exactly as possible what he meant."</p>

<div class="oc-center white_background noexpand">

<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:336px;height:280px" data-ad-client="ca-pub-1184791463292965" data-ad-slot="9361927867" /><br/></div>

<p>This working definition, while devoid of technical jargon for the sake of Bernstein's untrained audience, still manages to give us a good sense of the parameters he set for the "classical." They do not stretch widely enough to include improvisatory modernism (though he had a <a href="http://www.openculture.com/2015/04/leonard-bernsteins-introduction-to-jazz.html">high regard for jazz </a>as a separate category). But they do include much instrumental and choral European music from the start of the medieval period into the 20th century. The definition could be a much narrower one. "One of the first things you learn when you're introduced to classical music," <a href="http://www.classicalmpr.org/story/2013/10/15/what-is-classical-music">Jay Gabler writes at online radio station Classical MPR</a>, "is that the term 'classical' most properly describes music composed from about 1750 to 1820."</p>

<div class="oc-center" http://cdn8.openculture.com/="http://cdn8.openculture.com/">

<p>This means Mozart and Haydn, most of Beethoven, but not Bach, Wagner, Debussy, or Copland. And certainly not aleatory experimentalists like John Cage, minimalists like Steve Reich, or atonal oddballs like Arnold Schoenberg. While Bernstein seems to settle the issue with relative ease, "musicologists," Gabler notes, "can stay up all night talking about the shape and trajectory of classical music, debating questions like the importance of the score, the role of improvisation, and the nature of musical form." These are the kinds of discussions one might have over the 1200-track Spotify playlist above, "<a href="https://open.spotify.com/user/ulyssestone/playlist/1SIPkkACMDJSw9htur00jw">The History of Classical Music–From Gregorian Chant to Górecki</a>." (If you need Spotify's software, <a href="https://www.spotify.com/download/">download it here</a>.)</p>

<p>We begin with the 11th century church music of Leonin and Perotin, two composers associated with Notre Dame who are credited with "<a href="https://spinditty.com/industry/Duels-Featuring-Former-US-President-Andrew-Jackson">the beginning of modern music</a>" for their use of polyphony and various rhythmic modes. (Hear the especially haunting "Viderunt Omnes" by Leonin at the top of the post.) The playlist, created by a curator who goes by Ulysses Classical, then takes us through the late Medieval and Renaissance periods and into the Baroque, exemplified by Handel, Bach, Vivaldi, Pachelbel, Scarlatti, and others. Beethoven and Mozart get their due, but not more so than Dvořák and Tchaikovsky.</p>

<p>By the time we reach the 20th century, we begin to move quite far from the formalism of Bernstein's definition and into the strange realms of Schoenberg, Messiaen, Ligeti, Reich, and Philip Glass, with whom this history ends. Obviously the strict periodization Gabler mentions cannot contain all of what we mean by classical music, but just how much can the designation encompass atonal experimental modernism and still be a coherent concept? Let the musicologists debate. For those of us who approach this music as a form of pure pleasure, it's enough just to sit back and listen.</p>

<p><strong>Related Content:</strong></p>

<p><a href="http://www.openculture.com/2012/03/leonard_bernsteins_masterful_lectures_on_music.html">Leonard Bernstein’s Masterful Lectures on Music (11+ Hours of Video Recorded at Harvard in 1973)</a></p>

<p><a href="http://www.openculture.com/2015/08/stream-58-hours-of-classical-music-for-studying-working-or-simply-relaxing.html">Stream 58 Hours of Free Classical Music Selected to Help You Study, Work, or Simply Relax</a></p>

<p><a href="http://www.openculture.com/2014/03/the-world-concert-hall-listen-to-the-best-live-classical-music-concerts-for-free.html">The World Concert Hall: Listen To The Best Live Classical Music Concerts for Free</a></p>

<p><em><a href="http://about.me/jonesjoshua">Josh Jones</a> is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at <a href="https://twitter.com/jdmagness">@jdmagness</a></em></p>

<!-- permalink:http://www.openculture.com/2017/06/the-history-of-classical-music-in-1200-tracks-from-gregorian-chant-to-gorecki.html--><p><a rel="nofollow" href="http://www.openculture.com/2017/06/the-history-of-classical-music-in-1200-tracks-from-gregorian-chant-to-gorecki.html">The History of Classical Music in 1200 Tracks: From Gregorian Chant to Górecki</a> is a post from: <a href="http://www.openculture.com">Open Culture</a>. Follow us on <a href="https://www.facebook.com/openculture">Facebook</a>, <a href="https://twitter.com/#!/openculture">Twitter</a>, and <a href="https://plus.google.com/108579751001953501160/posts">Google Plus</a>, or get our <a href="http://www.openculture.com/dailyemail">Daily Email</a>. And don't miss our big collections of <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freeonlinecourses">Free Online Courses</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freemoviesonline">Free Online Movies</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/free_ebooks">Free eBooks</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freeaudiobooks">Free Audio Books</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freelanguagelessons">Free Foreign Language Lessons</a>, and <a href="http://www.openculture.com/free_certificate_courses">MOOCs</a>.</p>

<div class="feedflare">

<a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=xTUFe8KIpZU:YfSG5EBGbEs:yIl2AUoC8zA"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?d=yIl2AUoC8zA" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=xTUFe8KIpZU:YfSG5EBGbEs:V_sGLiPBpWU"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?i=xTUFe8KIpZU:YfSG5EBGbEs:V_sGLiPBpWU" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=xTUFe8KIpZU:YfSG5EBGbEs:gIN9vFwOqvQ"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?i=xTUFe8KIpZU:YfSG5EBGbEs:gIN9vFwOqvQ" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=xTUFe8KIpZU:YfSG5EBGbEs:qj6IDK7rITs"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?d=qj6IDK7rITs" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=xTUFe8KIpZU:YfSG5EBGbEs:I9og5sOYxJI"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?d=I9og5sOYxJI" border="0"></img></a>

</div><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~r/OpenCulture/~4/xTUFe8KIpZU" height="1" width="1" alt="" /> |

| 2:30p | Watch a Surreal 1953 Animation of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Tell-Tale Heart,” Voted the 24th Best Cartoon of All Time Animation studio UPA—United Productions of America—is best known these days as the studio that gave us Mr. Magoo and Gerald McBoing Boing (which inspired a certain website). But the studio, originally created by three former Disney employees, wanted to broaden horizons back in the 1950s, and created this quite disturbing adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell Tale Heart,” narrated by the venerable James Mason. Due to its adult subject matter, it was the first animated film to receive an “X” rating And while it does feature some traditional cell animation, there’s a mix of techniques that keep the film in the realm of the dreamlike and avant-garde: sudden zooms, shadows that fade in and out, flattened perspectives, inventive use of chiaroscuro. In this film one can see both the future careers of Roger Corman and Dario Argento, both grabbing influences left and right. In fact, though designer Paul Julian is best known for his background work at Warner Bros. animation studios (he also is known as the creator of the Road Runner’s beep-beep sound), he wound up providing director Roger Corman with artwork for movies like Dementia 13 and The Terror. UPA continued to produce films with its modern and flat space-age aesthetic during the ‘50s, but it never really hit these adult heights again. The ‘60s however, would pick up from where UPA left off. Julian's “The Tell Tale Heart” was voted the 24th greatest cartoon of all time, in a 1994 survey of 1,ooo animation professionals. It was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film. We hope you enjoy this glimpse into disturbia. It will be added to our list of Free Animations, a subset of our collection, 1,150 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc.. Related Content: Edgar Allan Poe’s the Raven: Watch an Award-Winning Short Film That Modernizes Poe’s Classic Tale Hear Orson Welles Read Edgar Allan Poe on a Cult Classic Album by The Alan Parsons Project Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here. Watch a Surreal 1953 Animation of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Tell-Tale Heart,” Voted the 24th Best Cartoon of All Time is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

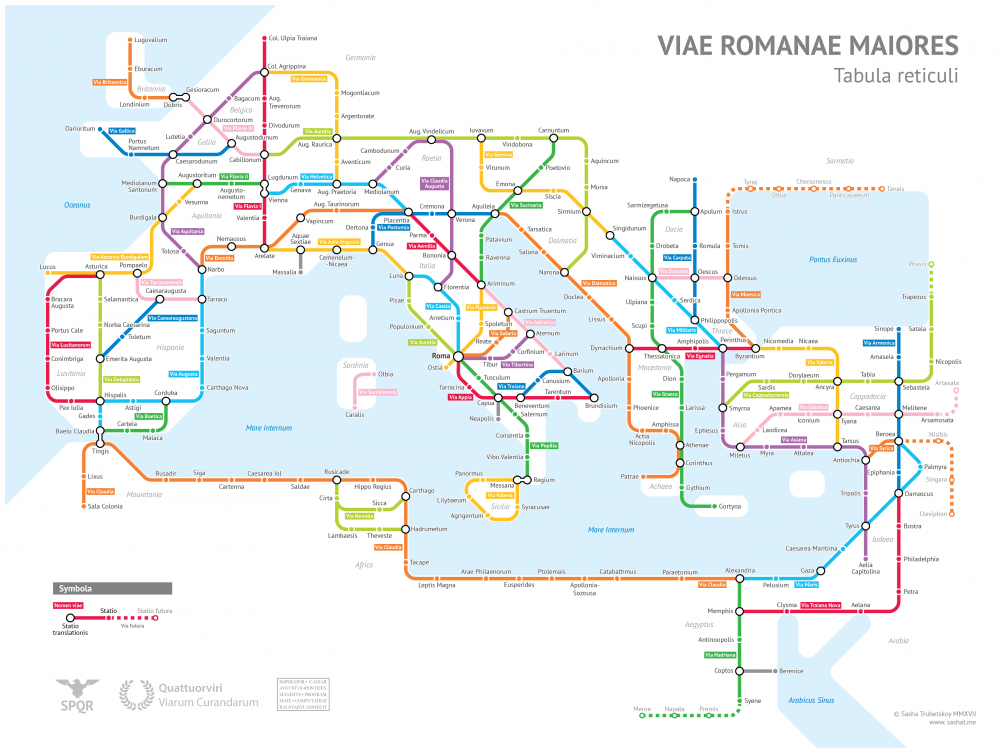

| 5:00p | Ancient Rome’s System of Roads Visualized in the Style of Modern Subway Maps  Sasha Trubetskoy, an undergrad at U. Chicago, has created a "subway-style diagram of the major Roman roads, based on the Empire of ca. 125 AD." Drawing on Stanford’s ORBIS model, The Pelagios Project, and the Antonine Itinerary, Trubetskoy's map combines well-known historic roads, like the Via Appia, with lesser-known ones (in somes cases given imagined names). If you want to get a sense of scale, it would take, Trubetskoy tells us, "two months to walk on foot from Rome to Byzantium. If you had a horse, it would only take you a month." You can view the map in a larger format here. And if you follow this link and send Trubetskoy a few bucks, he promises to email you a crisp PDF for printing. Enjoy. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: Designer Massimo Vignelli Revisits and Defends His Iconic 1972 New York City Subway Map Watch the Destruction of Pompeii by Mount Vesuvius, Re-Created with Computer Animation (79 AD) Fashionable 2,000-Year-Old Roman Shoe Found in a Well The Rise & Fall of the Romans: Every Year Shown in a Timelapse Map Animation (753 BC -1479 AD) Ancient Rome’s System of Roads Visualized in the Style of Modern Subway Maps is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/06/08 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |