[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, June 14th, 2017

- Heidegger Meets Van Gogh: Art, Freedom and Technology - Web video - Simon Glendinning, London School of Economics

- Dark Matter of the Mind - Web video - Daniel Everett, Bentley University

- Fear and Trembling in the 21st Century - Web video - Clare Carlisle, King’s College London

- Knowledge and Rationality - Web Video - Corine Besson, University of Sussex

- Life, Meaning and Morality - Web video - Christopher Hamilton, King’s College, London

- Minds, Morality and Agency - Web video - Mark Rowlands, University of Miami

- On Romantic Love - Web video - Berit Brogaard, University of Miami

- The Human Compass - Web video - Janne Teller

- The Meaning of Life - Web video - Steve Fuller, University of Warwick

- The Universe As We Find It - Web video - John Heil, Washington University in St Louis

- Unveiling Reality - Web video - Bryan Roberts, London School of Economics

- Why the World Does Not Exist - Web video - Markus Gabriel, Freiburg Institute of Advanced Study.

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | The Art of the Marbler: An Enchanting Film on the Centuries-Old Craft of Making Handmade Marbled Paper The current mode of scandal in business and politics involves email and tweets rather than memoranda. But we do not yet live a paperless world, even if you haven’t dusted your printer in months. Book production and sales continue to rise, for example, defying predictions of a few years back that eBooks would overtake print. Even if we have to someday make paper in laboratories rather than forests and mills, it’s hard to imagine readers ever letting go of the pleasures of its textures and smells, or of simple, yet satisfying acts like placing a favorite paper bookmark in the creases. We do, however, seem to live in a largely stationary-less world, and we have for some time. As the fine art of making artisanal papers recedes into history, so too does the printing of books with marbled covers and pages. Yet, if you have on your shelf hardback books anywhere from 30 to 130 years old, you no doubt have a few with marbled patterns on them or in them. And if you’ve ever wondered about this strange art form, wonder no more. The 1970 British educational film, “The Art of the Marbler,” above, offers a broad overview of this fascinating “material which has covered books for many centuries.”

Produced by Bedfordshire Record Office of Cockerell Marbling and directed by K.V. Whitbread, the short film is a marvel of quaintness. It effortlessly achieves the kind of quirk Wes Anderson’s films strive for simply by being itself. We learn that every marbled paper, unlike Christmas wrapping paper, is a “separate and unique original.” And that the process is precious and specialized, and nearly all done by hand. Lest we become too enamored of the idea that marbling is strictly a historical curiosity these days, the mesmerizing video above from 2011 by Seyit Uygur shows us up close how his parents perform the art of Ebru, Turkish for paper marbling. Marbling, the “printmaking technique that basically looks like capturing a galaxy on a page,” as Emma Dajska writes at Rookie, became quite popular in the Islamic world, where intricate patterns stood in lieu of portraits. But the process originated neither in England nor Turkey, but in China and, later, Japan, where it is known as Suminagashi, or “floating ink.” The Japanese technique, as you can see in the video tutorial above from Chrystal Shaulis, is very different from British Marbling or Turkish Ebru, seeming to combine the methods of Jackson Pollack with those of the Zen gardener. However it’s done, the results, as “The Art of the Marbler” tells and shows us, are each one a “unique original.” "The Art of the Marbler" will be added to our list of Free Documentaries, a subset of our collection, 1,150 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc.. Related Content: The Making of Japanese Handmade Paper: A Short Film Documents an 800-Year-Old Tradition How Ink is Made: The Process Revealed in a Mouth-Watering Video Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Art of the Marbler: An Enchanting Film on the Centuries-Old Craft of Making Handmade Marbled Paper is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

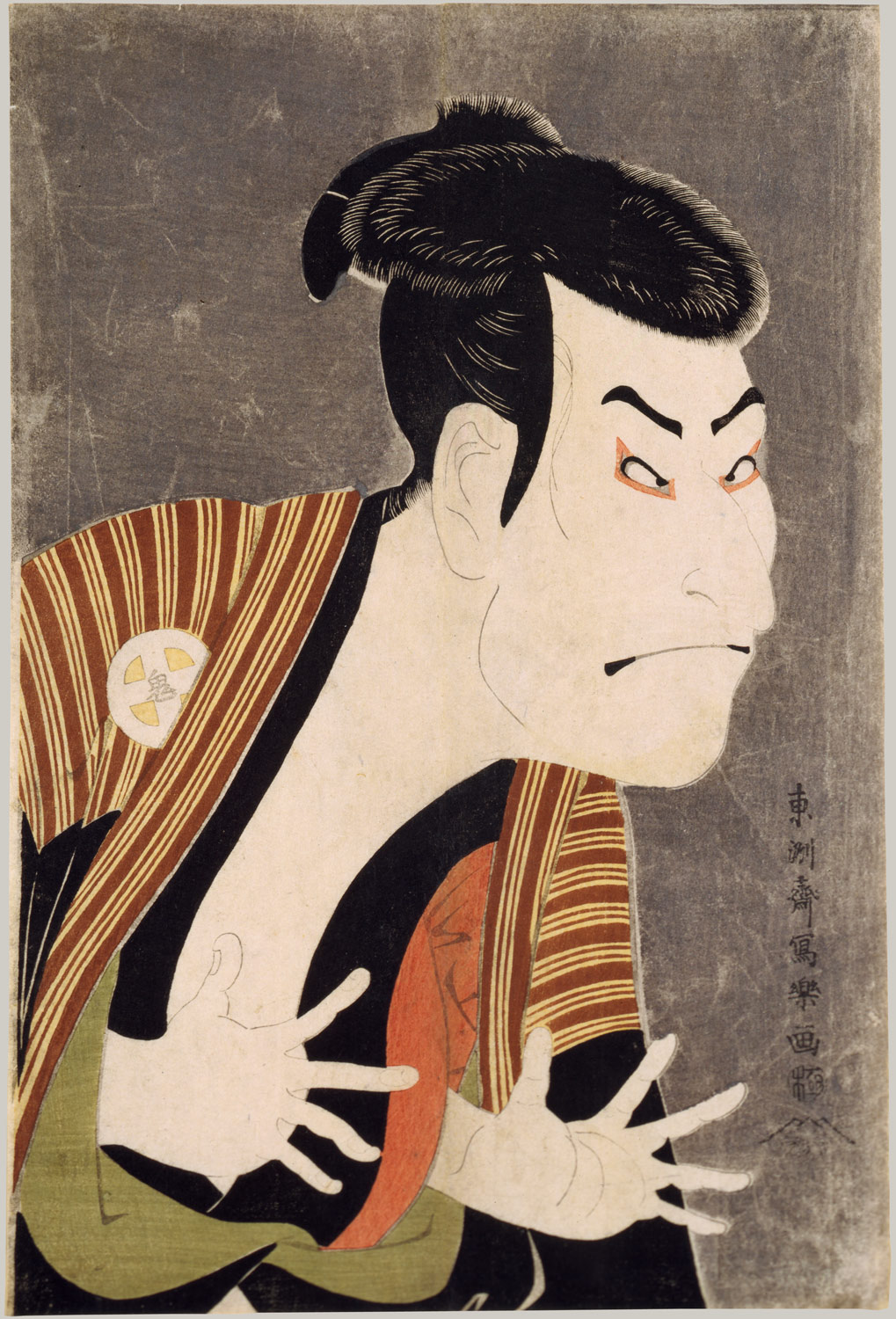

| 2:30p | Japanese Kabuki Actors Captured in 18th-Century Woodblock Prints by the Mysterious & Masterful Artist Sharaku   "Kabuki," as a cultural reference, has traveled astonishingly far beyond the early seventeenth-century Japan in which the form of kabuki theatre originated. Even 21st-century Westerners are quick to use the word when describing anything elaborately performative or melodramatic: in the negative sense, it criticizes an excessive artificiality; in the positive one, it praises complex, nuance-laden mastery. Many scholars of kabuki will disagree about when, exactly, kabuki had its heyday, but none would doubt the immortality, for a kabuki actor of the late eighteenth century, granted by a Sharaku portrait.  Also known to us as Tōshūsai Sharaku (probably not his real name), Sharaku worked in the form of yakusha-e woodblock prints, a kind of ukiyo-e focusing on actors, but only for a scant ten months in 1794 and 1795, and not always to a warm public reception. "Renowned for creating visually bold prints that gave rare revealing glimpses into the world of kabuki," says the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "he was not only able to capture the essential qualities of kabuki characters, but his prints also reveal, often with unflattering realism, the personalities of the actors who were famous for performing them." Breaking somewhat from ukiyo-e portraitist tradition, "Sharaku did not idealize his subjects or attempt to portray them realistically. Rather, he exaggerated facial features and strove for psychological realism."  Nobody knows much about this mysterious artist's background or his life after yakusha-e. During it, he designed over 140 prints, and potentially many more, given the number that remain unverifiable as his work. Though he did occasional portraits of sumo wrestlers and warriors, the majority of his portraits depict actors, and seldom in an idealized fashion.  That sense of heightened reality also brought with it a certain vitality to that point unseen in yakusha-e; art historian Muneshige Narazaki wrote that Sharaku could, within a single print of a kabuki actor or scene, depict "two or three levels of character revealed in the single moment of action forming the climax to a scene or performance."  At the top of the post, we have three prints from the fourth and final period of Sharaku's short career: Ichikawa Ebizō as Kudō Saemon Suketsune, Ichikawa Danjūrō VI as Soga no Gorō Tokimune, and Sawamura Sōjūrō III as Satsuma Gengobei. Below that, from top to bottom, appear Ōtani Oniji III in the Role of the Servant Edobei, Segawa Kikujurō III as Oshizu, Wife of Tanabe (one of the many female roles played without exception by male actors after the kabuki theatre attained its current form), Nakamura Nakazō II as the farmer Tsuchizō, actually Prince Koretaka, and Arashi Ryūzō I as Ishibe Kinkichi, which set an auction record for an ukiyo-e print by selling for €389,000 at Piasa in 2009.  If you want to learn a little more about kabuki theatre itself, have a look at TED-Ed's four-minute primer on its history. Though many of us may now regard kabuki as a high classical art form, it began as a "people's" version of the aristocratic noh theatre, and an avant-garde one at that. Its very name appears to derive from the Japanese verb kabuku, which means "to lean" or "to be out of the ordinary." Sharaku must have seen how incisively this theatre of the unusual, already long established by this day, could present the elements of real life; did he consider it his mission, during his woodblock-designing stint, to bring the elements of real life into its portraiture?  Related Content: Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600-1915) Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition Splendid Hand-Scroll Illustrations of The Tale of Genjii, The First Novel Ever Written (Circa 1120) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Japanese Kabuki Actors Captured in 18th-Century Woodblock Prints by the Mysterious & Masterful Artist Sharaku is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:23p | Meet Alexander Graham Bell, Inventor of the Telephone and Popular TV Pitchman Mr. Watson, come here! I want you to tell me why I keep showing up in television commercials. Is it because they think I invented the television?

Not at all, my dear Mr. Bell. A second's worth of research reveals that a 21-year-old upstart named Philo Taylor Farnsworth invented television. By 1927, when he unveiled it to the public, you’d already been dead for five years. You invented the telephone, a fact of which we’re all very aware. Though you might want to look into intellectual property law.... Historic figures make popular pitchmen, especially if - like Lincoln, Copernicus, and a red hot Alexander Hamilton, they’ve been in the grave for over 100 years. (Hint - you’ve got five years to go.) Or you could take it as a compliment! You’ve made an impression so lasting, the briefest of establishing shots is all we television audiences need to understand the advertiser's premise. Thusly can you be co-opted into selling the American public on the apparently revolutionary concept of chicken for breakfast, above. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg! Mr. Watson gets a cameo in your 1975 ad for Carefree Gum. You definitely come off the better of the two. You’re an obvious choice for a recent AT&T spot tracing a line from your revelatory moment to 20-something hipsters wielding smartphones and sparklers on a Brooklyn rooftop. Their devices aren’t the only thing connecting you. It’s also the beards… Apologies for the beardlessness of this 10 year old, low-budget spot for Able Computing in Papua New Guinea. Possibly the costumer thought Einstein invented the phone? Or maybe the creative director was counting on the local viewing audience not to sweat the small stuff. Your invention matters more than your facial hair. Lego took a cue from the 80s Muppet Babies craze by sending you back to childhood. They also saddled you and your mom with American accents, a regrettably common practice. I bet you would’ve liked Legos, though. They’re like blocks. As for this one, your guess is as good as mine. Readers, please share your favorite ads featuring historic figures in the comments below. Related Content: Hear the Voice of Alexander Graham Bell for the First Time in a Century Thomas Edison’s Silent Film of the “Fartiste” Who Delighted Crowds at Le Moulin Rouge (1900) Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. See her onstage in New York City in Paul David Young’s Faust 3, an indictment of the Trump administration that adapts and mangles Goethe's Faust (Parts 1 and 2) and the Gospels in the King James translation, as well as bits of Yeats, Shakespeare, Christmas carols, Stephen Foster, John Donne, Heiner Müller, Julia Ward Howe, and Abel Meeropol. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Meet Alexander Graham Bell, Inventor of the Telephone and Popular TV Pitchman is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:37p | Take Free Philosophy Courses from The Institute of Art and Ideas: From “The Meaning of Life” to “Heidegger Meets Van Gogh”

Back in 2014, we told you about how The Institute of Art and Ideas (IAI) launched IAI Academy -- an online educational platform that features free courses from world-leading scholars "on the ideas that matter." They have since put online a number of philosophy courses, many striving to address questions that affect our lives today. We've listed a number of them below, and added them to our list of 150+ Free Online Philosophy courses. For a complete list of IAI Academy courses, visit this page. Note: The courses are all free. However, to take a course you will need to create a user account. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: Take First-Class Philosophy Courses Anywhere with Free Oxford Podcasts The Great War and Modern Philosophy: A Free Online Course Søren Kierkegaard: A Free Online Course on the “Father of Existentialism” Introduction to Political Philosophy: A Free Yale Course 1200 Free Online Courses from Top UniversitiesTake Free Philosophy Courses from The Institute of Art and Ideas: From “The Meaning of Life” to “Heidegger Meets Van Gogh” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

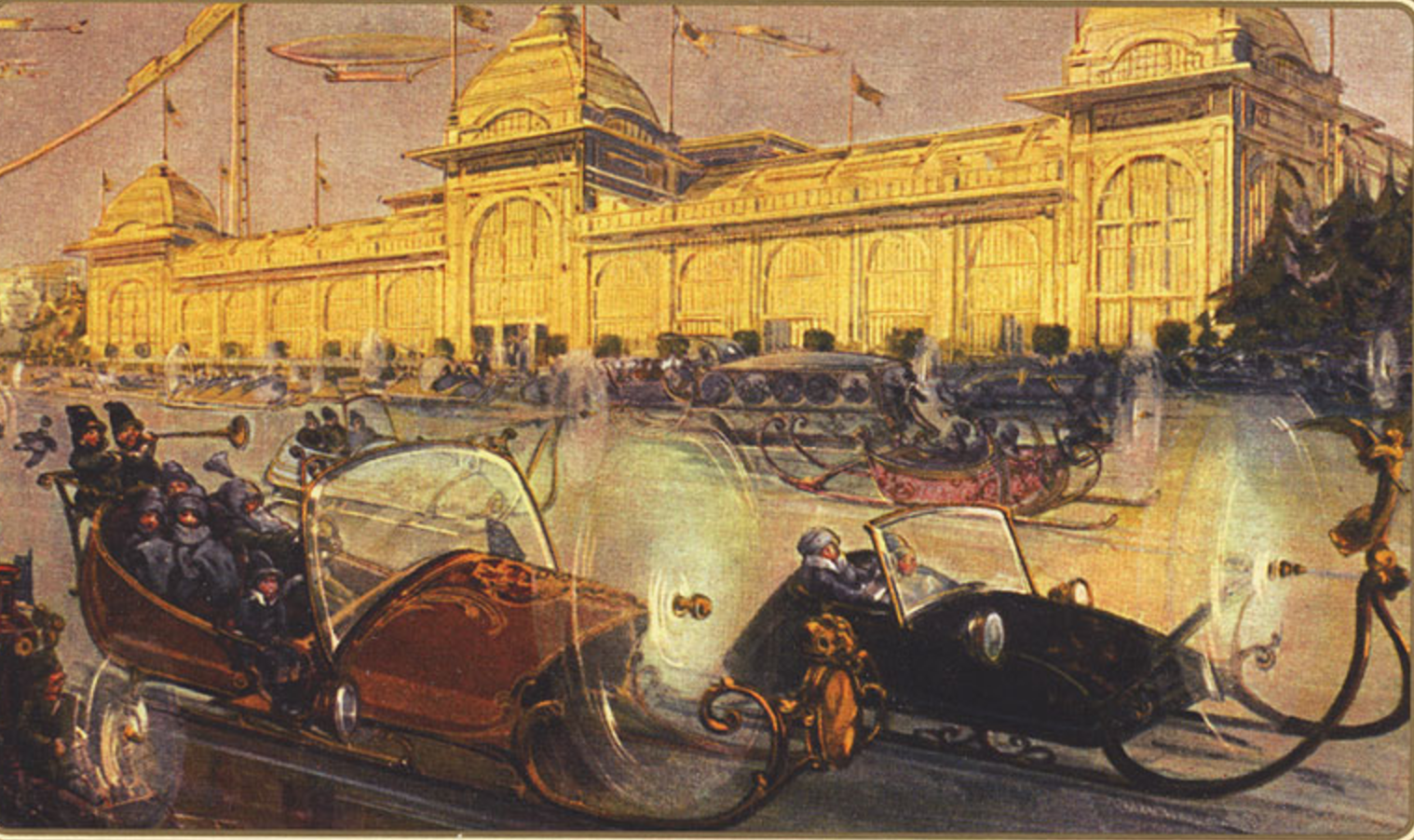

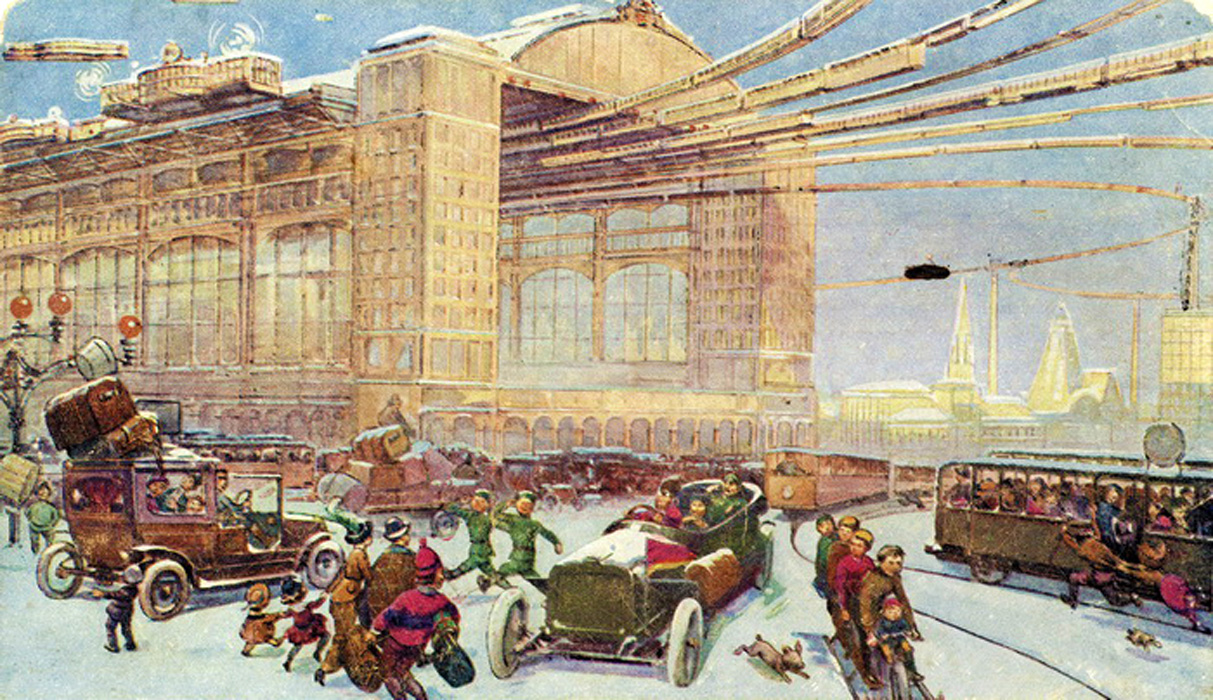

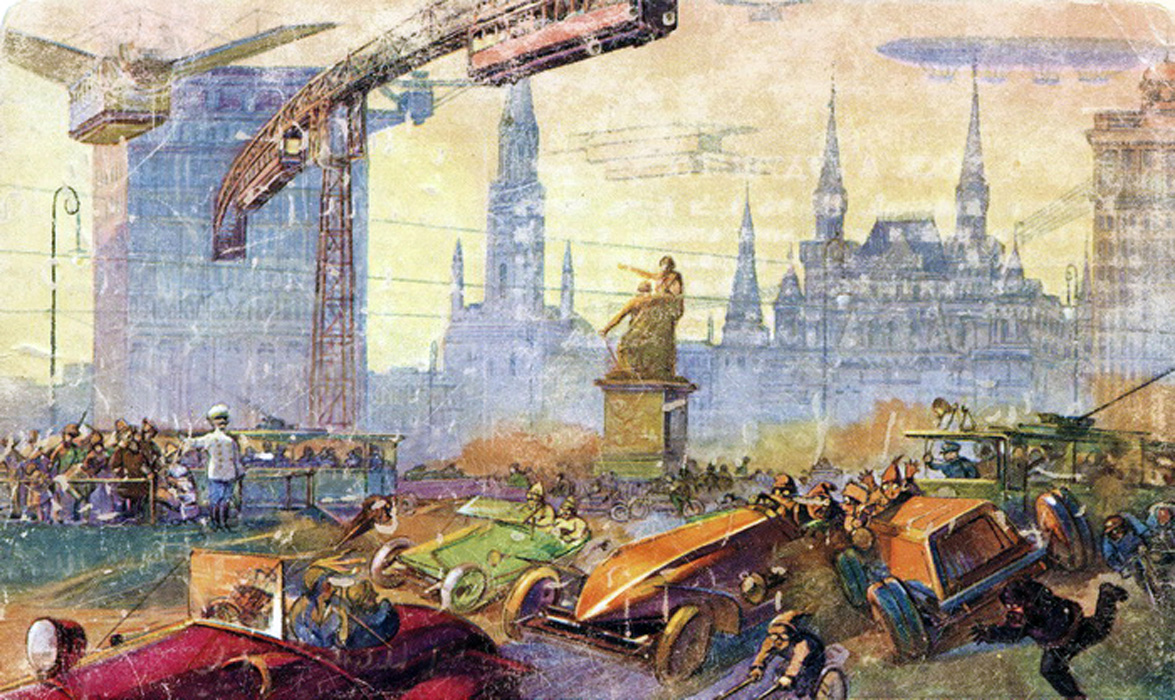

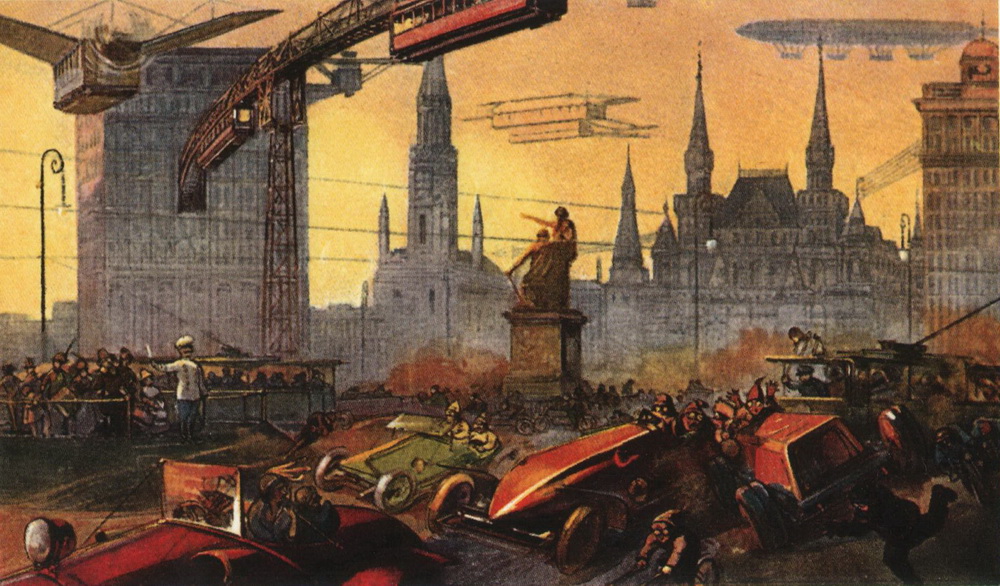

| 7:00p | How Russian Artists Imagined in 1914 What Moscow Would Look Like in 2259

In the days of popular retrofuturism—say, the first half of the twentieth century—people tended to imagine the world of tomorrow looking very much like the world of today, only with a lot more flying cars, monorails, and videophones. This is true whether those doing the imagining were titans of industry, marketing mavens, idealistic Soviets, or subjects of the Tsar, though we might think that people living under an ancient monarchical system might not expect much change. In some ways we might be right, but as we can see in the 1914 postcards here—printed as Russia entered World War I—the country did anticipate a modern, technological future, though one that still closely resembled its present.

Perhaps few but the most far-sighted of Russians predicted what the ailing empire would endure in the years to come—the disaster of the Great War, and the waves of Revolution and Civil War. Certainly, whoever painted these images foresaw no such catastrophic upheaval. Although purporting to show us a view of Moscow in the 23rd century, they show the city very happily “still under monarchical rule,” writes A Journey Through Russian Culture, going about its daily life just as it did over three hundred years earlier, “with the addition of everything from subways to airborne public transportation, things probably seen as standard methods of transport for the future.”

Of course, there would be hot-rodded sleds on St. Petersburg Highway with headlights, fancy windshields, and what look like Christmas elves perched in them. Lubyanska Square, further up, would still host military parades of men on horseback, as children whizzed by on motorbikes and subway trains rumbled underneath. The Central Railway Station, above, might seem entirely unchanged, until one looks up, and sees elevated trams streaming out of the terminal like spider’s silk. Red Square, however, just below, would apparently host drag races, while people in trams and giant dirigibles looked on from above.

The images have a children’s book quality about them and the festive air of holiday cards. (If you read Russian, you can learn more about them here and here.) They were apparently rediscovered only recently when a chocolate company called Eyinem reprinted them on their packaging. Like so much retrofuturism, these seem—in their bustling, yet safe, cheerful orderliness—tailor-made for nostalgic trips through Petrovsky Park, rather than imaginative leaps into the great unknown. For that, we must turn to Russian Futurism, which, both before and after World War and the Revolution, imagined, helped bring about, but didn't quite survive the massive technological and political disruption of the next two decades.

See more of these Tsarist-futurist postcards at the site Meet the Slavs. Related Content: Soviet Artists Envision a Communist Utopia in Outer Space Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Russian Artists Imagined in 1914 What Moscow Would Look Like in 2259 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/06/14 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |