[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, June 23rd, 2017

- 20+ video lessons where Herbie teaches you how to "improvise, compose, and develop your own sound."

- 10+ original piano transcriptions, including 5 exclusive solo performances.

- A downloadable class workbook.

- And the chance to have the 14-time Grammy winner critique your work.

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Willie Nelson & Ray Charles Sing a Moving Duet “Seven Spanish Angels”: A Beautiful Bridge That Crosses Musical & Racial Divides Having grown up in Georgia surrounded by blues, gospel, and country music—and having studied the classical composers when he was learning piano—Ray Charles was bound to become a polymath of musical genres. He is often credited with creating soul music, but a less remembered but equally important part of his career was recording one of the first major crossover records, 1962’s Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music. The record execs at ABC-Paramount understandably thought it would be career suicide, but Charles, who had a contract that gave him creative control (and ownership of his master tapes), insisted. It went on to be both a commercial and critical success, creating racial and genre bridges during the Civil Rights Movement. So the above video of Willie Nelson performing a duet with Charles was not the oddity that it may first seem. The two recorded “Seven Spanish Angels” for the former’s Half Nelson album of duets, and the single would go on to be the most successful of Charles' country releases, reaching the top of the country charts in 1985. The song has become a favorite country cover, and judging by the YouTube comments is a favorite at funerals, seeing that it's a tale of an outlaw couple pledging their love and going out shootin’. (That is, it’s good for honoring devoted couples, not for criminal parents. But we’re not here to judge.) The 1984 TV special from which this excerpt came was filmed at the Austin Opry House, and featured Charles on five more songs with Nelson, including “Georgia on My Mind” and “I Can't Stop Loving You.” And although he didn’t write “Georgia on My Mind” (Hoagy Carmichael did), Charles’ name is synonymous with the well-loved soul number. That being said, Willie Nelson’s cover of the song reached higher in the charts in 1978, a kind of thank you to Charles for his country work. After this 1984 video, the two would duet nine years later for Willie Nelson’s 60th birthday celebration where they once again sang “Seven Spanish Angels,” a testament to their long friendship. Related Content: Willie Nelson–Young, Clean-Shaven & Wearing a Suit–Sings Early Hits at the Grand Ole Opry (1962) Animated Interview: The Great Ray Charles on Being Himself and Singing True Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here. Willie Nelson & Ray Charles Sing a Moving Duet “Seven Spanish Angels”: A Beautiful Bridge That Crosses Musical & Racial Divides is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

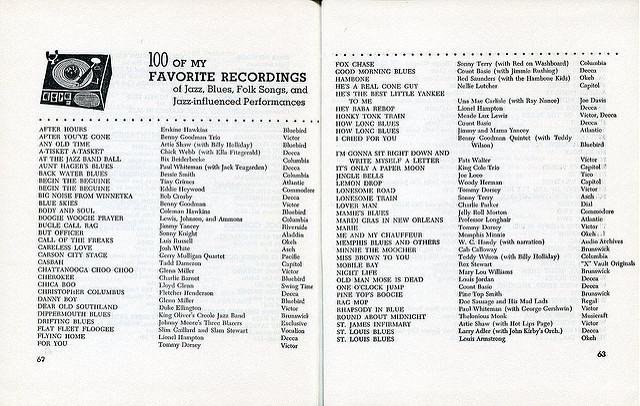

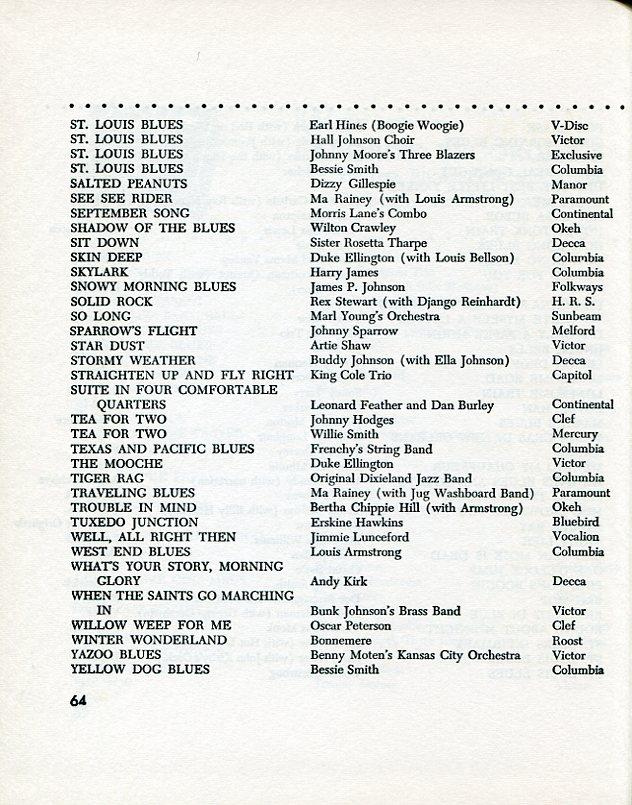

| 10:30a | Langston Hughes Creates a List of His 100 Favorite Jazz Recordings: Hear 80+ of Them in a Big Playlist

Image by The Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons “Langston Hughes was never far from jazz,” writes Rebecca Cross at the NEA’s Art Works Blog. “He listened to it at nightclubs, collaborated with musicians from Monk to Mingus, often held readings accompanied by jazz combos, and even wrote a children’s book called The First Book of Jazz.” The 1955 book is a striking visual artifact, with illustrations by Cliff Roberts made to resemble jazz album covers of the period. Though written in simple prose, it has much to recommend it to adults, despite its somewhat forced—literally—upbeat tone. “The book is very patriotic,” we noted in an earlier post, “a fact dictated by Hughes’ recent [1953] appearance before Senator McCarthy’s Subcommittee, which exonerated him on the condition that he renounce his earlier sympathies for the Communist Party and get with a patriotic program.”

Earlier statements on music had been more candid and close to the heart: “jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America,” Hughes wrote in a 1926 essay, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain”—“the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile.” The sweet bitterness of these sentiments may lie further beneath the surface thirty years later in The First Book of Jazz, but the children’s introduction to that thoroughly original African-American form made it clear. “For Hughes,” as Cross writes, “jazz was a way of life,” even when life was constrained by red scare repression.

Hughes invites his readers, of all ages, to share his passion, not only through his careful history and explanations of key jazz elements, but also through a list of recommendations in an appendix: “100 of My Favorite Recordings of Jazz, Blues, Folk Songs, and Jazz-Influenced Performances.” (View them in a larger format here: Page 1 - Page 2.) In the playlist below, you can hear 81 of Hughes’ selections: classic New Orleans jazz from Louis Armstrong, blues from Bessie Smith, “jazz-influenced” classical from George Gershwin, bebop from Thelonious Monk, swing from Count Basie, guitar gospel from Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and much more from Sonny Terry, Tommy Dorsey, Charlie Parker, Memphis Minnie, Billie Holiday, and oh so many more artists who moved the Harlem Renaissance poet to put “jazz into words” as he wrote in “Jazz as Communication,” an essay published the following year. If you need Spotify's free software, download it here. For Hughes, jazz was a broad category that embraced all black American music—not only the blues, ragtime, and swing but also, by the mid-fifties, rock and roll, which he believed, would “no doubt be washed back half forgotten into the sea of jazz” in years to come. But whatever the future held for jazz, Hughes had no doubt it would be “what you call pregnant,” and as fertile as its past. “Potential papas and mamas of tomorrow’s jazz are all known,” he concludes in his 1956 essay. “But THE papa and THE mama—maybe both—are anonymous. But the child will communicate. Jazz is a heartbeat—its heartbeat is yours. You will tell me about its perspectives when you get ready.” Just above, see Hughes recite the poem “Weary Blues” with jazz band accompaniment in a CBC appearance from 1958. Related Content: Langston Hughes Presents the History of Jazz in an Illustrated Children’s Book (1955) Watch Langston Hughes Read Poetry from His First Collection, The Weary Blues (1958) The Cry of Jazz: 1958’s Highly Controversial Film on Jazz & Race in America (With Music by Sun Ra) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Langston Hughes Creates a List of His 100 Favorite Jazz Recordings: Hear 80+ of Them in a Big Playlist is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Why Cartoon Characters Wear Gloves: A Curious Trip Through the History of Animation It’s rare for Disney to overlook a marketing opportunity. For years, Mouse Ears were the film studio’s theme park souvenir of choice, but recently the gift shops have started stocking white four-fingered gloves too. Perhaps not the most sensible choice for dipping into a bucket of jalapeño poppers or a $6 Mickey Pretzel with Cheese Sauce, but the gloves have undeniable reach when it comes to cartoon history. Bugs Bunny wears them. So does Woody Woodpecker, Tom (though not Jerry), and Betty Boop's anthropomorphic doggie pal, Bimbo. As Vox’s Estelle Caswell points out above, the choice to glove Mickey and his early 20th-century cartoon brethren was born of practicality. The limited palette of black and white animation meant that most animal characters had black bodies—their arms disappeared against every inky expanse. It also provided artists with a bit of relief, back when animation meant endless hours of labor over hand drawn cells. Puffy gloves aren’t just a comical capper to bendy rubber hose limbs. They’re also way easier to draw than realistic phalanges. As Walt Disney himself explained: We didn't want him to have mouse hands, because he was supposed to be more human. So we gave him gloves. Five Fingers looked like too much on such a little figure, so we took one away. That was just one less finger to animate. Caswell digs deeper than that, unearthing a surprising cultural comparison. White gloves were a standard part of blackface performers’ minstrel show costumes. Audiences who packed theaters for touring minstrel shows were the same people lining up for Steamboat Willie. Comic animation has evolved both visually and in terms of content over its near hundred year history, but animators have a tendency to revere the history of their profession. Thusly do South Park's animators bestow spotless white gloves upon Mr. Hankey the Christmas Poo. "America's favorite cat and mouse team," the Simpsons' Itchy and Scratchy, mete out their horrifically violent punishment in pristine white gloves. Clearly some things are worth preserving… Related Content: The Disney Cartoon That Introduced Mickey Mouse & Animation with Sound (1928) Disney’s 12 Timeless Principles of Animation Demonstrated in 12 Animated Primers Free Animated Films: From Classic to Modern Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine, appearing onstage in New York City through June 26 in Paul David Young’s Faust 3. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Why Cartoon Characters Wear Gloves: A Curious Trip Through the History of Animation is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:00p | The First Avant Garde Animation: Watch Walter Ruttmann’s Lichtspiel Opus 1 (1921) Most visual art forms, like painting, sculpture, or still photography, take a while to get from representation to abstraction, but cinema had a head start, thanks in large part to the groundbreaking efforts of a German filmmaker named Walter Ruttmann. He did it in the early 1920s, not much more than twenty years after the birth of the medium itself, with Lichtspiel Opus 1, which you can watch above. Lichtspiel Opus 2, 3, and 4 follow it in the video, but though equally enchanting on an aesthetic level, especially in their integration of imagery and music, none hold the impressive distinction of being the very first abstract film ever screened for the public that Lichtspiel Opus 1 does. "Following the First World War, Ruttmann, a painter, had moved from expressionism to full-blown abstraction," writes Gregory Zinman in A New History of German Cinema. As early as 1917, "Ruttmann argued that filmmakers 'had become stuck in the wrong direction,' due to their misunderstanding of cinema's essence,'" which prompted him to use "the technologically derived medium of film to produce new art, calling for 'a new method of expression, one different from all the other arts, a medium of time. An art meant for our eyes, one differing from painting in that it has a temporal dimension (like music), and in the rendition of a (real or stylized) moment in an event or fact, but rather precisely in the temporal rhythm of visual events." To realize this new art form, Ruttmann came up with, and even patented, a kind of animation technique. Once a painter, always a painter, he found a way to make films using oils and brushes. As experimental animations scholar William Moritz described it, Ruttmann created Lichtspiel Opus I with images "painted with oil on glass plates beneath an animation camera, shooting a frame after each brush stroke or each alteration because the wet paint could be wiped away or modified quite easily. He later combined this with geometric cut-outs on a separate layer of glass." The result still looks and feels quite unlike the animation we know today, and certainly resembled nothing any of its first viewers had even seen when it premiered in Germany in April 1921. This puts it ahead, chronologically, of the work of Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling, creators of some of the earliest masterpieces of abstract film in the early 1920s, not screened for the public until 1923. Alas, when Hitler came to power and declared abstract art "degenerate," according to Bennett O'Brian at Pretty Clever Films, Ruttmann didn't flee but "remained in Germany and worked with Leni Riefenstahl on The Triumph of the Will." In wartime, he "was put to work directing propaganda reels like 1940’s Deutsche Panzer which follows the manufacturing process of armored tanks." Alas, "his decision to stay in Germany during the war would eventually cost Ruttmann his life," which ended in 1944 with a mortal wound endured while filming a battle in Russia. But however ideologically and morally questionable his later work, Ruttmann, with his pioneering journey into abstract animation, opened up a creative realm only accessible to filmmakers that, even as we approach an entire century after Lichtspiel Opus I, filmmakers have far from fully explored. Related Content: Watch “Geometry of Circles,” the Abstract Sesame Street Animation Scored by Philip Glass (1979) Watch the Surrealist Glass Harmonica, the Only Animated Film Ever Banned by Soviet Censors (1968) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The First Avant Garde Animation: Watch Walter Ruttmann’s Lichtspiel Opus 1 (1921) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 10:06p | Herbie Hancock to Teach His First Online Course on Jazz MasterClass is on fire these days. In recent months, the new online course provider has announced the development of online courses taught by leading figures in their fields. And certainly some names you'll recognize: Dr. Jane Goodall on the Environment, David Mamet on Dramatic Writing, Steve Martin on Comedy, Aaron Sorkin on Screenwriting, Gordon Ramsay on Cooking, Christina Aguilera on Singing, and Werner Herzog on Filmmaking. Now add this to the list: Herbie Hancock on Jazz. Writes MasterClass:

The course won't get started until this fall, but you can pre-enroll now. Priced at $90, the course will feature: Apparently this will be the first time Hancock has ever taught a course online. Learn more about Herbie Hancock Teaches Jazz here. And find more MasterClass courses here. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: Watch Herbie Hancock Rock Out on an Early Synthesizer on Sesame Street (1983) Herbie Hancock Presents the Prestigious Norton Lectures at Harvard University: Watch Online Herbie Hancock to Teach His First Online Course on Jazz is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/06/23 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |