[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, June 30th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Garry Kasparov Will Teach an Online Course on Chess Quick FYI: Garry Kasparov will be teaching an online course on chess this fall, apparently his first online course ever. A grandmaster and six-time World Chess Champion, Kasparov held the highest chess rating (until being surpassed by Magnus Carlsen in 2013) and also the record for consecutive tournament victories (15 in a row). In his upcoming course, featuring 20 video lessons, Kasparov will give students "detailed lessons," covering "his favorite openings and advanced tactics," all of which will help students "develop the instincts and philosophy to become a stronger player." Students who pre-enroll now will get early access to the course. The $90 course is being offered by MasterClass, the same venture developing classes with these other luminaries--Herbie Hancock on Jazz, Jane Goodall on the Environment, David Mamet on Dramatic Writing, Steve Martin on Comedy, Aaron Sorkin on Screenwriting, Gordon Ramsay on Cooking, Christina Aguilera on Singing, and Werner Herzog on Filmmaking. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: A Free 700-Page Chess Manual Explains 1,000 Chess Tactics in Plain English Claymation Film Recreates Historic Chess Match Immortalized in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey A Human Chess Match Gets Played in Leningrad, 1924 Play Chess Against the Ghost of Marcel Duchamp: A Free Online Chess Game Watch Bill Gates Lose a Chess Match in 79 Seconds to the New World Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen Garry Kasparov Will Teach an Online Course on Chess is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 4:30p | Arnold Schoenberg Creates a Hand-Drawn, Paper-Cut “Wheel Chart” to Visualize His 12-Tone Technique

"These go up to eleven," Spinal Tap famously said of the amplifiers that, so they claimed, took them to a higher level in rock music. But the work of Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg, one of the best-known figures in the history of avant-garde music, went up to twelve — twelve tones, that is. His "twelve-tone technique," invented in the early 1920s and for the next few decades used mostly by he and his colleagues in the Second Viennese School such as Alban Berg, Anton Webern, and Hanns Eisler, allowed composers to break free of the traditional Western system of keys that limited the notes available for use in a piece, instead granting each note the same weight and making none of them central.

This doesn't mean that composers using Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique could just use notes at random in complete atonality, but that a new set of considerations would organize them. "He believed that a single tonality could include all twelve notes of the chromatic scale," writes Bradford Bailey at The Hum, "as long as they were properly organized to be subordinate to tonic (the tonic is the pitch upon which all others are referenced, in other words the root or axis around which a piece is built)." The mathematical rigor underlying it all required some explanation, and often mathematical and musical concepts — mathematics and music being in any case intimately connected — become much clearer when rendered visually.

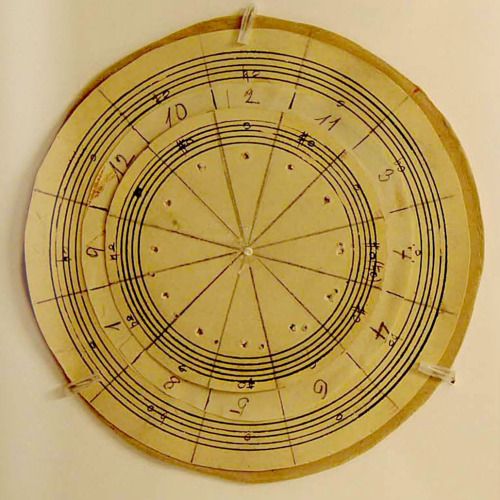

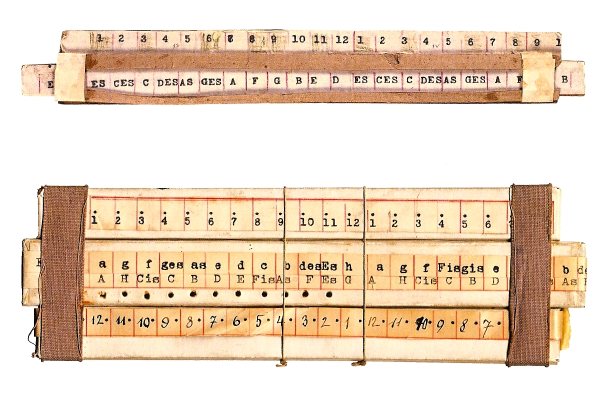

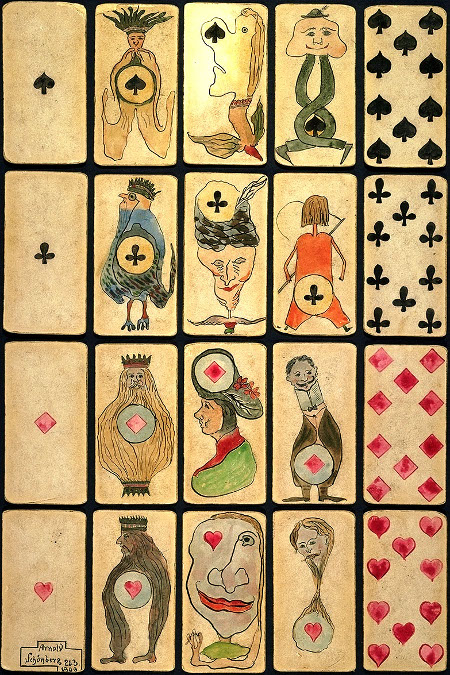

Hence Schoenberg's twelve-tone wheel chart pictured at the top of the post, one of what Arnold Schoenberg's Journey author Allen Shawn describes as "no fewer than twenty-two different kinds of contraptions" — including "charts, cylinders, booklets, slide rules" — "for transposing and deriving twelve-tone rows" needed to compose twelve-tone music. (See the slide ruler above too.) "The distinction between 'play' and 'work' is already hard to draw in the case of artists," writes Shawn, "but in Schoenberg's case it is especially hard to make since he brought discipline, originality, and playfulness to many of his activities." These also included making special playing cards (two of whose sets you can see here and here) and even his own version of chess. As Shawn describes it, Koalitionsscach, or "Coalition Chess," involves "the armies of four countries arrayed on the four sides of the board, for which he designed and constructed the pieces himself." Instead of an eight-by-eight board, Coalition Chess uses a ten-by-ten, and the pieces on it "represent machine guns, artillery, airplanes, submarines, tanks, and other instruments of war." The rules, which "require that the four players form alliances at the outset," add at least a dimension to the age-old standard game of chess — a form that, like traditional Western music, humanity will still be struggling to master decades and even centuries hence. But apparently, for a mind like Schoenberg's, chess and music as he knew them weren't nearly challenging enough. Related Content: Vi Hart Uses Her Video Magic to Demystify Stravinsky and Schoenberg’s 12-Tone Compositions Interviews with Schoenberg and Bartók John Coltrane Draws a Picture Illustrating the Mathematics of Music Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Arnold Schoenberg Creates a Hand-Drawn, Paper-Cut “Wheel Chart” to Visualize His 12-Tone Technique is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

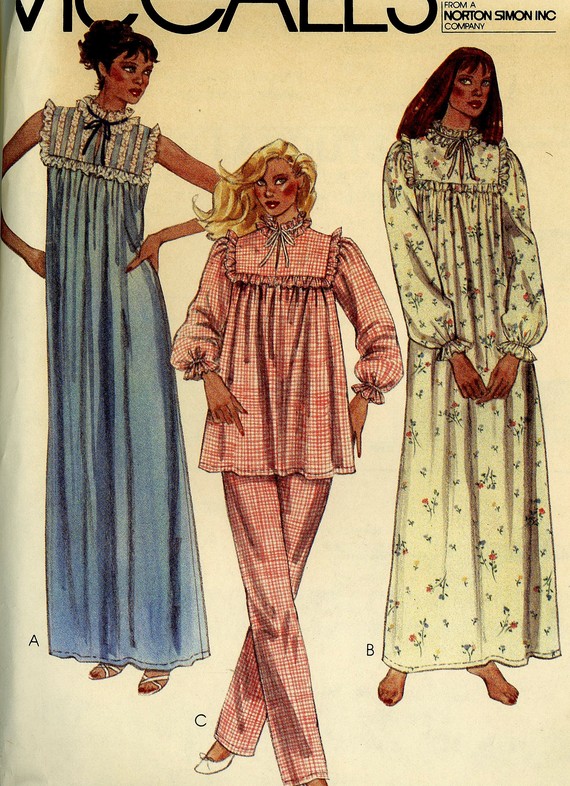

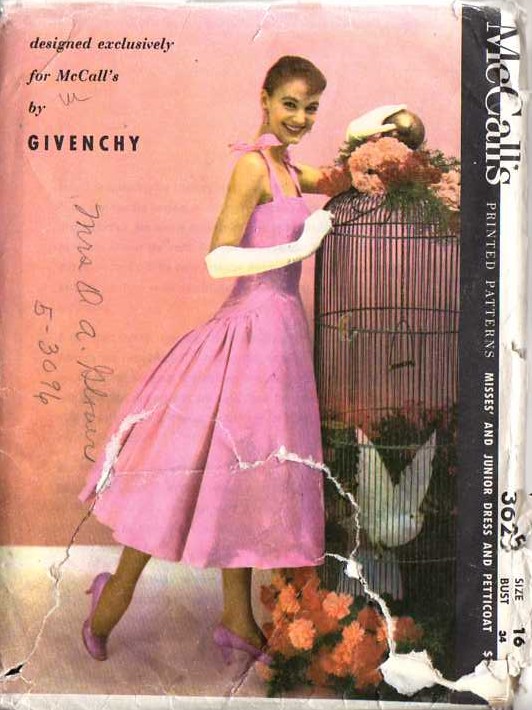

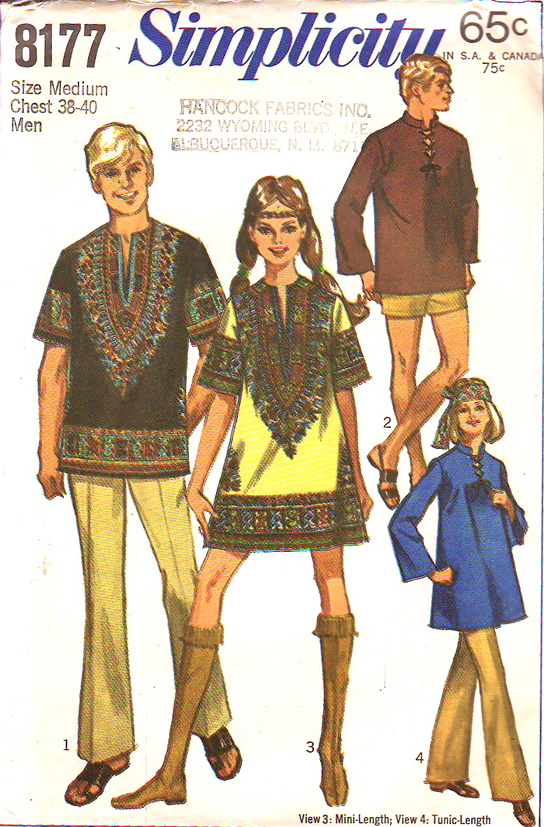

| 6:00p | Browse a Collection of Over 83,500 Vintage Sewing Patterns

My costume design professor at Northwestern University, Virgil Johnson, delighted students with his formula for period clothing. I have forgotten some of the mathematic and semantic particulars—does dressing someone five years behind the times a “frumpy” character make? Or is it merely one? I do recall some anxious hours, preparing for the school’s main stage production of the incestuous Jacobean revenge tragedy, ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore. The societal corruption of the play was underscored by having the supporting characters slouch around, snorting mimed cocaine in cutting edge, mid-80s Vogue Patterns … those big unstructured jackets were very a la mode, but they gobbled up a lot of high-budget fabric, and I didn’t want to be the one to make a costly sewing mistake.

What sticks in my mind most clearly is that 20 years was the sweet spot, the appropriate amount of elapsed time to ensure that one would not appear dumpy, dowdy, or oblivious, but rather prudent and discerning. Donning a garment that was 15 years out of fashion might be daringly “retro,” but another five and that same garment could be heralded as “vintage.” The collaborative Vintage Pattern Wiki puts the magic number at 25, requesting that contributors make sure the patterns they post are from 1992 or earlier, and also out-of-print.

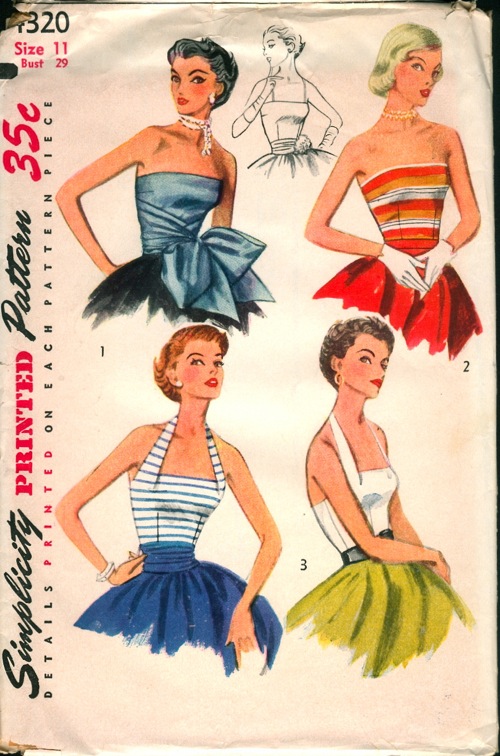

The browsable collection of over 83,500 patterns runs the gamut from Dynasty-inspired pussy bow power suits to Betty Draper-esque frocks featuring models in white gloves to an 1895 boys' Reefer Suit with fly-free short trousers. Visitors can narrow their search to focus on a particular garment, designer or decade. If you click these links, you can see patterns from the following decades: 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. The movie star collection is particularly fun. (Flattering or no, I’ve always wanted a pair of Katharine Hepburn pants…)

And it goes without saying that the dog days of summer are the perfect time to get a jump on your Halloween costume. Those who are itching to get sewing should check the links below each pattern envelope cover for vendors who have the pattern in stock and photos and posts by community members who have made that same garment. The prices and handwritten jottings of the original owners will also put you in a vintage mood. The hunt starts here.

Related Content: The Online Knitting Reference Library: Download 300 Knitting Books Published From 1849 to 2012 Frida Kahlo’s Colorful Clothes Revealed for the First Time & Photographed by Ishiuchi Miyako Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Browse a Collection of Over 83,500 Vintage Sewing Patterns is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:00p | How Ada Lovelace, Daughter of Lord Byron, Wrote the First Computer Program in 1842–a Century Before the First Computer I’ve never quite understood why the phrase “revisionist history” became purely pejorative. Of course, it has its Orwellian dark side, but all knowledge has to be revised periodically, as we acquire new information and, ideally, discard old prejudices and narrow frames of reference. A failure to do so seems fundamentally regressive, not only in political terms, but also in terms of how we value accurate, interesting, and engaged scholarship. Such research has recently brought us fascinating stories about previously marginalized people who made significant contributions to scientific discovery, such as NASA's “human computers,” portrayed in the book Hidden Figures, then dramatized in the film of the same name. Likewise, the many women who worked at Bletchley Park during World War II—helping to decipher encryptions like the Nazi Enigma Code (out of nearly 10,000 codebreakers, about 75% were women)—have recently been getting their historical due, thanks to “revisionist” researchers. And, as we noted in a recent post, we might not know much, if anything, about silent film star Hedy Lamarr’s significant contributions to wireless, GPS, and Bluetooth technology were it not for the work of historians like Richard Rhodes. These few examples, among many, show us a fuller, more accurate, and more interesting view of the history of science and technology, and they inspire women and girls who want to enter the field, yet have grown up with few role models to encourage them. We can add to the pantheon of great women in science the name Ada Byron, Countess of Lovelace, the daughter of Romantic poet Lord Byron. Lovelace has been renowned, as Hank Green tells us in the video at the top of the post, for writing the first computer program, “despite living a century before the invention of the modern computer.” This picture of Lovelace has been a controversial one. “Historians disagree,” writes prodigious mathematician Stephen Wolfram. “To some she is a great hero in the history of computing; to others an overestimated minor figure.” Wolfram spent some time with “many original documents” to untangle the mystery. “I feel like I’ve finally gotten to know Ada Lovelace,” he writes, “and gotten a grasp on her story. In some ways it’s an ennobling and inspiring story; in some ways it’s frustrating and tragic.” Educated in math and music by her mother, Anne Isabelle Milbanke, Lovelace became acquainted with mathematics professor Charles Babbage, the inventor of a calculating machine called the Difference Engine, “a 2-foot-high hand-cranked contraption with 2000 brass parts.” Babbage encouraged her to pursue her interests in mathematics, and she did so throughout her life. Widely acknowledged as one of the forefathers of computing, Babbage eventually corresponded with Lovelace on the creation of another machine, the Analytical Engine, which “supported a whole list of possible kinds of operations, that could in effect be done in arbitrarily programmed sequence.” When, in 1842, Italian mathematician Louis Menebrea published a paper in French on the Analytical Engine, “Babbage enlisted Ada as translator,” notes the San Diego Supercomputer Center's Women in Science project. “During a nine-month period in 1842-43, she worked feverishly on the article and a set of Notes she appended to it. These are the source of her enduring fame.” (You can read her translation and notes here.) In the course of his research, Wolfram pored over Babbage and Lovelace’s correspondence about the translation, which reads “a lot like emails about a project might today, apart from being in Victorian English.” Although she built on Babbage and Menebrea’s work, “She was clearly in charge” of successfully extrapolating the possibilities of the Analytical Engine, but she felt “she was first and foremost explaining Babbage’s work, so wanted to check things with him.” Her additions to the work were very well-received—Michael Faraday called her “the rising star of Science”—and when her notes were published, Babbage wrote, “you should have written an original paper.” Unfortunately, as a woman, “she couldn’t get access to the Royal Society’s library in London,” and her ambitions were derailed by a severe health crisis. Lovelace died of cancer at the age of 37, and for some time, her work sank into semi-obscurity. Though some historians have seen her as simply an expositor of Babbage’s work, Wolfram concludes that it was Ada who had the idea of “what the Analytical Engine should be capable of.” Her notes suggested possibilities Babbage had never dreamed. As the Women in Science project puts it, "She rightly saw [the Analytical Engine] as what we would call a general-purpose computer. It was suited for 'developping [sic] and tabulating any function whatever. . . the engine [is] the material expression of any indefinite function of any degree of generality and complexity.' Her Notes anticipate future developments, including computer-generated music." In a recent episode of the BBC’s In Our Time, above, you can hear host Melvyn Bragg discuss Lovelace’s importance with historians and scholars Patricia Fara, Doron Swade, and John Fuegi. And be sure to read Wolfram’s biographical and historical account of Lovelace here. Related Content: How 1940s Film Star Hedy Lamarr Helped Invent the Technology Behind Wi-Fi & Bluetooth During WWII The Contributions of Women Philosophers Recovered by the New Project Vox Website Real Women Talk About Their Careers in Science Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Ada Lovelace, Daughter of Lord Byron, Wrote the First Computer Program in 1842–a Century Before the First Computer is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/06/30 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |