[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, July 12th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Discover Dr. Seuss’s Audacious Advertisements from the 1930s & 40s: All on Display in a Digital Archive

I well remember learning that Dr. Seuss’s real name was Theodor Geisel, mostly because I found Theodor Geisel was just as much fun to say as “Dr. Seuss.” Both names rolled around in the mouth, did somersaults and backflips off the tongue like the author’s multitude of strangely rubbery characters. With his Rube Goldberg machines, miniscule Whos, enormous Hortons, and mountains of comic absurdity, Seuss is like Swift for kids, his stories full of fantastic satire alongside much good clean common sense. Books like Horton Hears a Who and The Grinch Who Stole Christmas are chock full of “positive messages,” writes Amy Chyao at the Harvard Political Review, as well as trenchant social critique for five-year-olds.

Among the many lessons, “embracing diversity is perhaps the single most salient one embedded in many of Dr. Seuss’s books.” Geisel did not always espouse this value. There are those who read Horton’s refrain, “a person’s a person no matter how small,” as penance for work he did as a political cartoonist during World War II, when he drew what Jonathan Crow described in a previous post as “breathtakingly racist” depictions of the Japanese, promoting the bigotry that led to violence and the internment of Japanese Americans, an action he vigorously supported. You can see many of his political cartoons at UC San Diego’s digital library, “Dr. Seuss Went to War.” UCSD also hosts an online archive of Geisel’s advertising work, which sustained him throughout much of the 30s and 40s, and not all of which has aged well either.

Geisel later expressed regret for his blanket anti-Japanese attitudes after a trip to Japan in 1953. And he later made several anti-racist cartoons against Jim Crow laws and anti-Semitism. These might have been meant to atone for more of his less well-known work, advertisements featuring crude, ugly stereotypes of Africans and Arabs.

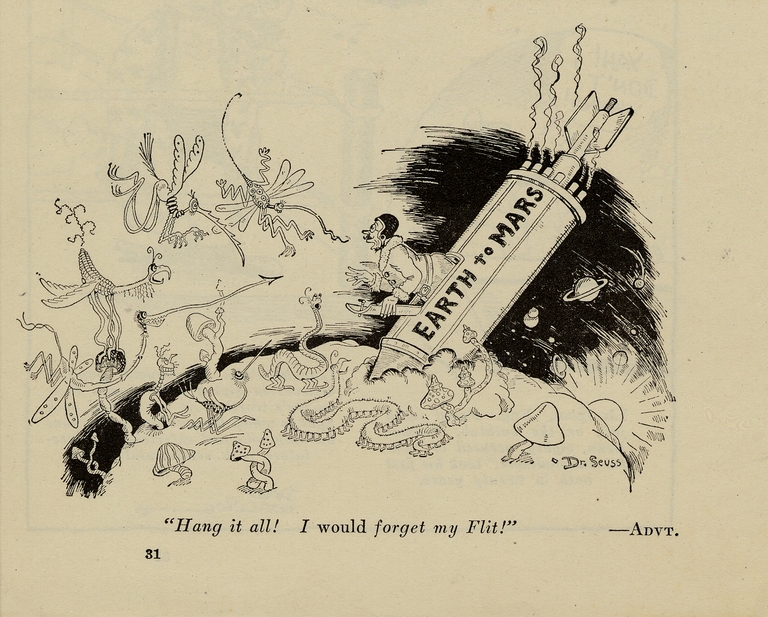

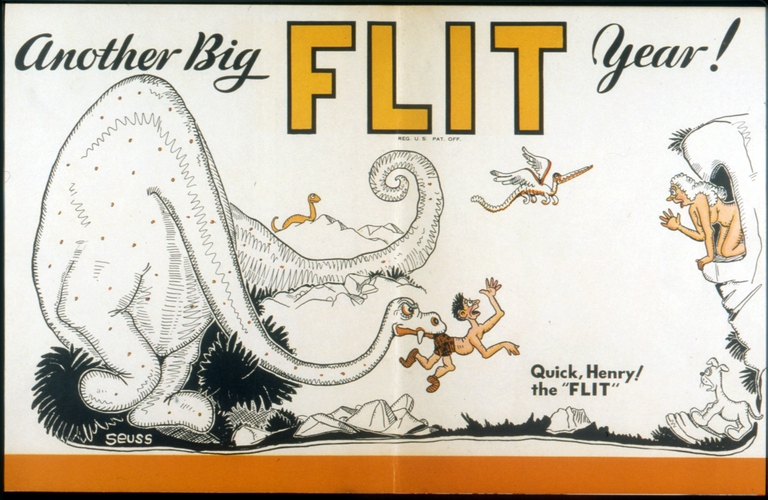

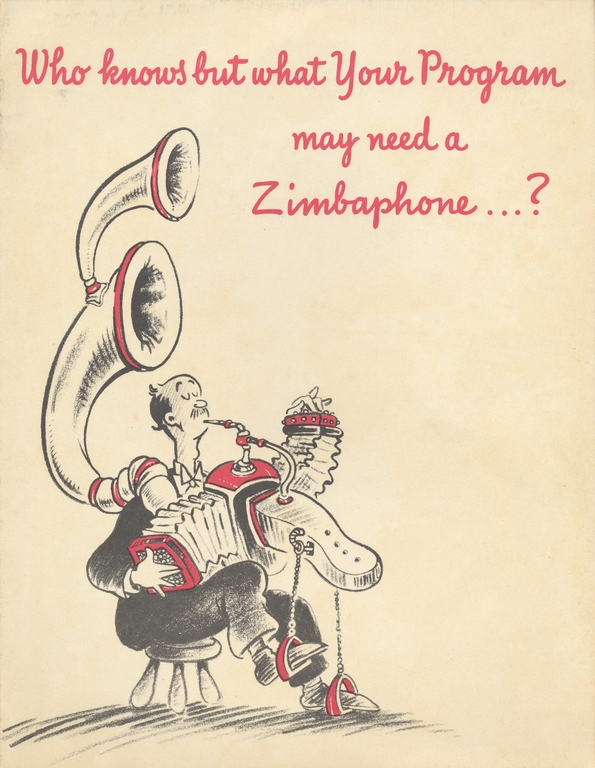

You will find some of these ads in the USCD archive; Geisel did truck in some blatantly inflammatory images. But he mostly drew innocuous, yet visually exciting, cartoons like the one at the top, one of the dozens of ads he drew during a 17-year campaign for Flit, an insect repellant made by Standard Oil.

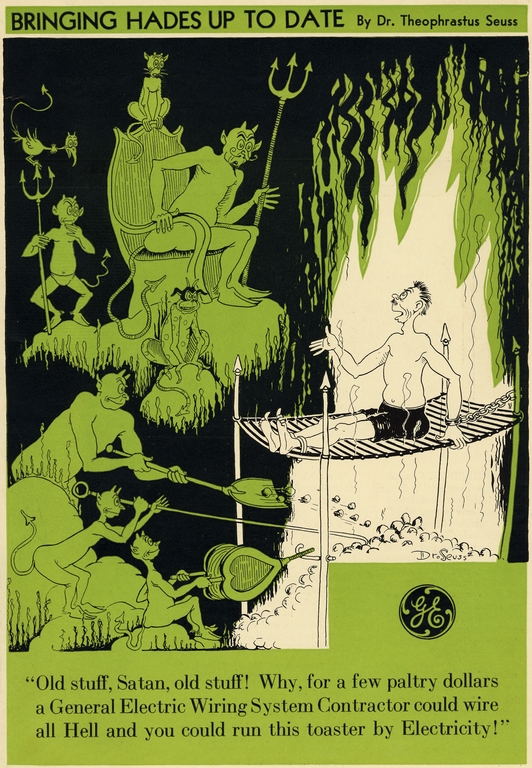

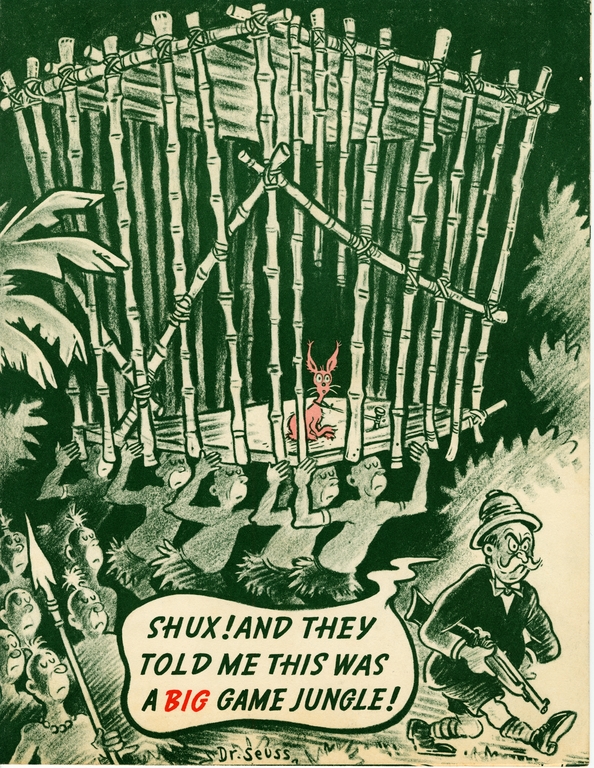

Geisel did ads for Standard Oil’s main product, promoting Essolube motor oil, further up, with the kind of creature that would later inhabit his children’s books. He got irreverently high concept with a GE ad set in hell, published explicitly under the pen name Dr. Theophrastus Seuss. And just above, in a brochure for the National Broadcasting Company, he introduces the visual aesthetic of Horton’s jungle, with a troupe of stereotypical grass-skirted Africans that might have come from one of Hergé’s offensive colonialist Tintin comics. (Both Seuss’s and Hergé’s early work are testaments to the common co-existence of progressive politics with often contemptuous or condescending treatment of nonwhite people in the early twentieth century.)

The Seuss advertisements archive shows us the artist’s development from visual puns and quirks to the fully-fledged mechanical surrealism of his mature style, as in the National Broadcasting Company brochure above, with its musical contraption the “Zimbaphone,” a precursor to the many cacophonous, overcomplicated instruments to come. It is when he is at his most inventive that Geisel is at his best. When he abandoned lazy, mean-spirited stereotypes, his work embraced a world of joyous possibility and weirdness. Related Content: Dr. Seuss Draws Anti-Japanese Cartoons During WWII, Then Atones with Horton Hears a Who! Dr. Seuss’ World War II Propaganda Films: Your Job in Germany (1945) and Our Job in Japan (1946) Neil Gaiman Reads Dr. Seuss’ Green Eggs and Ham Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Discover Dr. Seuss’s Audacious Advertisements from the 1930s & 40s: All on Display in a Digital Archive is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:00p | 100 Years of Cinema: New Documentary Series Explores the History of Cinema by Analyzing One Film Per Year, Starting in 1915 Film has played an integral part in almost all of our cultural lives for decades and decades, but when did we invent it? "We have evidence of man experimenting with moving images from a time when we still lived in caves," says the narrator of the video series One Hundred Years of Cinema. "Pictures of animals painted on cave walls seemed to dance and move in the flickering firelight." From there the study of cinema jumps ahead to the work of stop-motion photography pioneer Eadweard Muybridge, Louis Le Prince's building of the first single-lens movie camera, the invention of the kinetoscope, and the Lumière brothers' first projection of a motion picture before an audience. The birth of cinema, historians generally agree, happened when these events did, around the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth, and so the first episode of 100 Years of Cinema covers the years 1888 through 1914. But then, in 1915, comes D.W. Griffith's groundbreaking and still deeply controversial feature The Birth of a Nation, which the narrator calls "one of the most important films in cinema history." 100 Years of Cinema thus gives The Birth of a Nation its own episode, and in each subsequent episode it moves forward one year but adheres to the same format, picking out one particular movie through which to tell that chapter of the story of film. For 1916 we learn about 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, the first picture filmed underwater; for 1917, physical comedian Buster Keaton's debut The Butcher Boy; for 1918, The Ghost of Slumber Mountain, which dared to integrate live actors with stop-motion clay animation. And so does 100 Years of Cinema tell the story of film's first century as the story of innovation after innovation after innovation, doing so through obscurities as well as such pillars of the film-studies curriculum as Nanook of the North, Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis, and Man with a Movie Camera. The series, which began last April, has recently put out about one new episode per month. Its most recent video covers Scarface — not Brian de Palma's tale of drug-dealing in 1980s Miami whose poster still adorns dorm-room walls today, but the 1932 Howard Hawks picture it remade. Here the original Scarface gets credited as one of the works that defined the American gangster film, leading not just to the version starring Al Pacino and his machine gun but to the likes of The Godfather, Boyz N the Hood, and Reservoir Dogs as well. Cinephiles, place your bets now as to whether 100 Years of Cinema will select any of those films for 1972, 1991, or 1992 — and start considering what each of them might teach us about the development of the cinema we enjoy today. You can view all of the existing episodes, moving from 1915 through 1931, below. And support 100 Years of Cinema over at this Patreon page. Related Content: The 100 Most Memorable Shots in Cinema Over the Past 100 Years Free MIT Course Teaches You to Watch Movies Like a Critic: Watch Lectures from The Film Experience The History of the Movie Camera in Four Minutes: From the Lumiere Brothers to Google Glass Cinema History by Titles & Numbers Hollywood, Epic Documentary Chronicles the Early History of Cinema Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. 100 Years of Cinema: New Documentary Series Explores the History of Cinema by Analyzing One Film Per Year, Starting in 1915 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:00p | Send a Text Message to SFMOMA, and They’ll Send Works of Art to Your Mobile Phone The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art--otherwise simply known as SFMOMA--has 34,678 artworks in its collections, only 5% of which it can put on display at any given time. That creates an accessibility problem. So the museum asked itself: "How can we provide a more comprehensive experience of our collection?" And they developed Send Me SFMOMA in response. Send Me SFMOMA is "an SMS service that provides an approachable, personal, and creative method of sharing the breadth of SFMOMA’s collection with the public." Here's how it works:

|

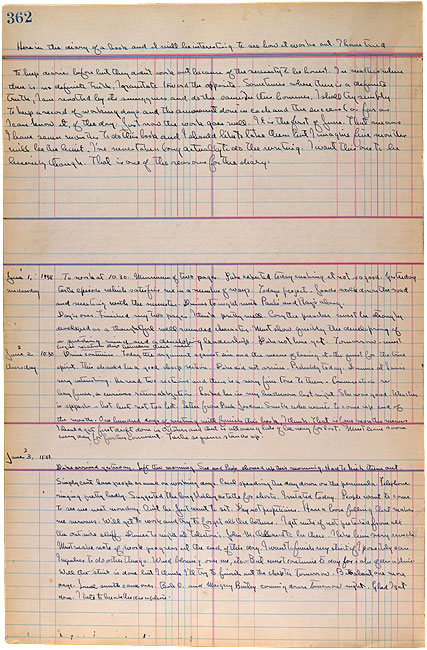

| 7:00p | John Steinbeck Has a Crisis in Confidence While Writing The Grapes of Wrath: “I am Not a Writer. I’ve Been Fooling Myself and Other People”

In a 1904 letter, Franz Kafka famously wrote, “a book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us,” a line immortalized in pop culture by David Bowie’s “Ashes to Ashes.” Where Bowie referred to the frozen emotions of addiction, the arctic waste inside Kafka may have had much more to do with the agony of writing itself. In the year that he composed his best-known work, The Metamorphosis, Kafka kept a tortured journal in which he confessed to feeling “virtually useless” and suffering “unending torments.” Not only did he need to break the ice, but “you have to dive down,” he wrote on January 30th, “and sink more rapidly than that which sinks in advance of you.” Whether as writers we find the evidence of Kafka’s crippling self-doubt to be a comfort I cannot say. For many people, no matter how successful, or prolific, some degree of pain inevitably attends every act of writing. And many, like Kafka, have left personal accounts of their most productive periods. John Steinbeck struggled mightily during the composition of his masterpiece, The Grapes of Wrath. His journal entries from the period tell the story of a frayed and anxious man overwhelmed by the seeming enormity of his task. But his example is instructive as well: despite his fragile mental state and lack of confidence, he continued to write, telling himself on June 11th, 1938, “this must be a good book. It simply must.” (See some of Steinbeck's handwritten entries in the image above, courtesy of Austin Kleon.) In setting the bar so high—“For the first time I am working on a real book,” he wrote—Steinbeck often felt crushed at the end of a day. “My whole nervous system in battered,” he wrote on June 5th. “I hope I’m not headed for a nervous breakdown.” He finds himself a few days later “assailed with my own ignorance and inability.” He continues in this vein. “Where has my discipline gone?” he asks in August, “Have I lost control?” By September he’s seeking perspective: “If only I wouldn’t take this book so seriously. It is just a book after all, and a book is very dead in a very short time. And I’ll be dead in a very short time too. So to hell with it.” The weight of expectation comes and goes, but he keeps writing. The “private fruit” of Steinbeck’s diary entries, writes Maria Popova, "is in many ways at least as important and morally instructive” as the novel itself. At least that may be so for writers who are also beset by devastating neuroses. For Steinbeck, the diary (published here) was “a tool of discipline” and “hedge against self-doubt.” This may sound counterintuitive, but keeping a diary, even when the novel stalls, is itself a discipline, and an acknowledgement of the importance of being honest with oneself, allowing turbulence and doldrums to be a conscious part of the experience. Steinbeck “feels his feelings of doubt fully, lets them run through him,” writes Popova, “and yet maintains a higher awareness that they are just that: feelings, not Truth.” His confrontations with negative capability can sound like “Buddhist scripture,” anticipating Ray Bradbury’s Zen in the Art of Writing. We needn’t attribute any religious significance to Steinbeck’s journals, but they do begin to sound like confessions of the kind many mystics have recorded over the centuries, including the imposter syndrome many a saint and bodhisattva has admitted to feeling. “I’m not a writer,” he laments in one entry. “I’ve been fooling myself and other people.” Nonetheless, no matter how excruciating, lonely, and confusing the effort, he resolved to develop a “quality of fierceness until the habit pattern of a certain number of words is established.” A ritual act, of a sort, which “must be a much stronger force than either willpower or inspiration.” In the audio above, hear actor Paul Hecht read excerpts from Steinbeck's diaries in an episode of the Morgan Library's Diary Podcast. You can read Steinbeck's diaries in the published volume, Working Days: The Journal of The Grapes of Wrath, 1938-1941. via Austin Kleon Related Content: John Steinbeck’s Six Tips for the Aspiring Writer and His Nobel Prize Speech See John Steinbeck Deliver His Apocalyptic Nobel Prize Speech (1962) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness John Steinbeck Has a Crisis in Confidence While Writing The Grapes of Wrath: “I am Not a Writer. I’ve Been Fooling Myself and Other People” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/07/12 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |