[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, July 19th, 2017

| Time | Event |

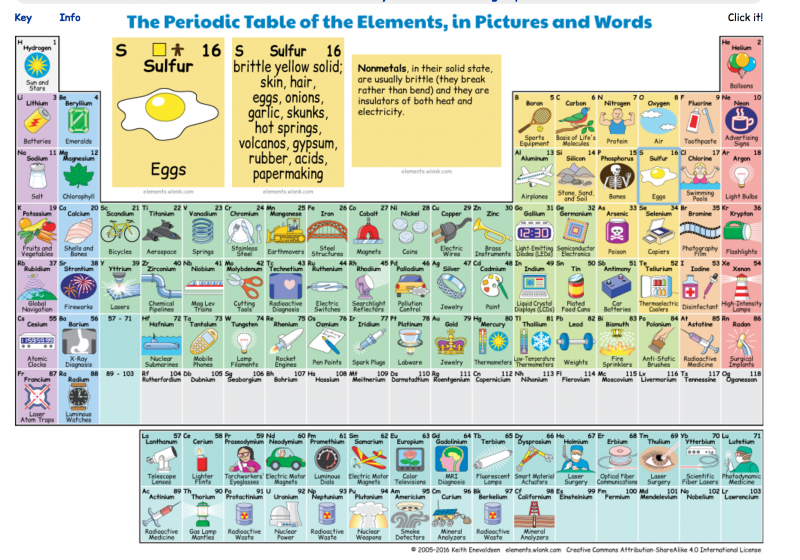

| 8:00a | Interactive Periodic Table of Elements Shows How the Elements Actually Get Used in Making Everyday Things

Keith Enevoldsen, a software engineer at Boeing, has created an Interactive Periodic Table of Elements. As you might expect, the table shows the name, symbol, and atomic number of each element. But even better, it illustrates the main way in which we use, or come into contact with, each element in everyday life. For example, Cadmium you will find in batteries, yellow paints, and fire sprinklers. Argon you'll encounter in light bulbs and neon tubes. And Boron in soaps, semiconductors and sports equipment. The Interactive Periodic Table of Elements (click here to access it) is a handy tool for chemistry teachers and students, but also for anyone interested in how the elements make a chemical contribution to our world. Also worth noting: Enevoldsen has released his Interactive Table under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: The Periodic Table of Elements Scaled to Show The Elements’ Actual Abundance on Earth Periodic Table Battleship!: A Fun Way To Learn the Elements “The Periodic Table Table” — All The Elements in Hand-Carved Wood World’s Smallest Periodic Table on a Human Hair “The Periodic Table of Storytelling” Reveals the Elements of Telling a Good Story Chemistry on YouTube: “Periodic Table of Videos” Wins SPORE Prize Interactive Periodic Table of Elements Shows How the Elements Actually Get Used in Making Everyday Things is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | How Insomnia Shaped Franz Kafka’s Creative Process and the Writing of The Metamorphosis: A New Study Published in The Lancet

Whatever else we take from it, Franz Kafka’s nightmarish fable The Metamorphosis offers readers an especially anguished allegory on troubled sleep. Filled with references to sleep, dreams, and beds, the story begins when Gregor Samsa awakens to find himself (in David Wylie’s translation) “transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin.” After several desperate attempts to roll off his back, Gregor begins to agonize, of all things, over his stressful working hours: “’Getting up early all the time,’ he thought, ‘it makes you stupid. You’ve got to get enough sleep.” Realizing that he has overslept and missed his five o’clock train, he agonizes anew over the frantic workday ahead, and we can hear in his thoughts the complaints of their author. “Sleep and lack thereof,” writes The Independent’s Christopher Hooten, “is of course a central theme in Kafka’s best known work…. It seems there was a strong dose of autobiography at play.” Chronically insomniac, Kafka wrote at night, then rose early each morning for his hated job at an insurance office. Though he made good use of restlessness, Kafka characterized his insomnia as much more than an inconvenient physical ailment. He thought of it in metaphysical terms, as a kind of soul-sickness. “Sleep,” he wrote in his diaries, “is the most innocent creature there is and sleepless man the most guilty.” Insomnia transformed Kafka into an unclean thing, quivering in fear of death. “Perhaps I am afraid that the soul, which in sleep leaves me, will not be able to return,” he confessed in a letter to German writer Milena Jesenská. Anxious expressions like this, writes Theresa Fisher, have led researchers to “speculate that Kafka’s pathological traits… indicate borderline personality disorder.” This posthumous diagnosis may be a leap too far. “Unearthing his insomnia, however,” and its effects on his life and work, “requires less speculation.” Kafka’s descriptions of his anxious insomniac writing habits have led Italian doctor Antonio Perciaccante and his wife and co-author Alessia Coralli to argue in a recent paper published in The Lancet that the writer composed much of his fiction in a state of something like lucid dreaming. In one diary entry, Kafka writes, “it was the power of my dreams, shining forth into wakefulness even before I fall asleep, which did not let me sleep.” Perciaccante and Coralli note that “this seems to be a clear description of a hypnagogic hallucination, a vivid visual hallucination experienced just before the sleep onset.” It’s something we’ve all experienced. Kafka, fearing sleep, stayed there as long as he could. Lest we think of his writing as therapeutic in some way, he gives no indication that it was so. Indeed, it seems that writing introduced more pain: “When I don’t write,” he told Jesenská, “I am merely tired, sad, heavy; when I do write, I am torn by fear and anxiety.” Kafka made many similar statements about sleep deprivation bringing him to “a depth almost inaccessible at normal conditions.” The visions he encountered, he wrote, “shape themselves into literature.” Through surveying the literature, biographies, interpretations, and the author’s diaries and letters to Jesenská and Felice Bauer, Perciaccante and Coralli pieced together a "psychophysiological" account of Kafka’s dream logic. As Perciaccante told ResearchGate in an interview, his study concerned itself less with the causes of Kafka’s sleeplessness. He admits “it’s difficult to classify Kafka’s insomnia.” Instead the authors concerned themselves with the effects of remaining in a hypnagogic state (a word, notes Drake Baer, that etymologically means “being abducted into sleep”), as well as Kafka’s awareness of his insomnia’s magical and debilitating power. Metamorphosis, says Perciaccante, in addition to a work about social and familial alienation, “may also represent a metaphor for the negative effects that poor quality sleep, short sleep duration, and insomnia may have on mental and physical health.” Had Kafka overcome his malady, he may never have written his best-known work. Indeed, he may not have written at all. “Perhaps there are other forms of writing,” he told Max Brod in 1922, “but I know only this kind, when fear keeps me from sleeping, I know only this kind.” Perciaccante and Coralli see Kafka’s insomniac torment as a primary theme in his work, but two dissenting voices, writer Saudmini Deo and forensic doctor and anthropologist Philippe Charlier, disagree. Writing into The Lancet to express their view, they assert that despite Kafka’s persistent laments and the squirmy fate of the autobiographical Gregor Samsa, the writer's “insomnia was not at all dehumanizing... but the exact opposite—ie, humanizing the self by bringing to surface elements of unconscious that guide most actions of our waking life.” Related Content: Franz Kafka’s Kafkaesque Love Letters How a Good Night’s Sleep — and a Bad Night’s Sleep — Can Enhance Your Creativity Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Insomnia Shaped Franz Kafka’s Creative Process and the Writing of The Metamorphosis: A New Study Published in The Lancet is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

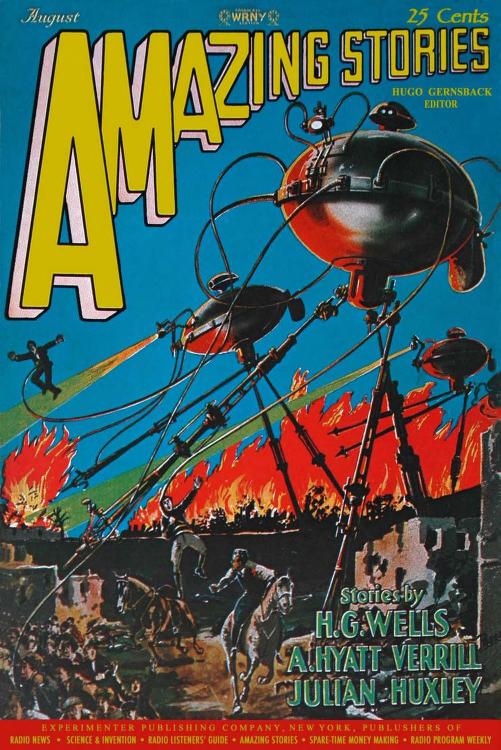

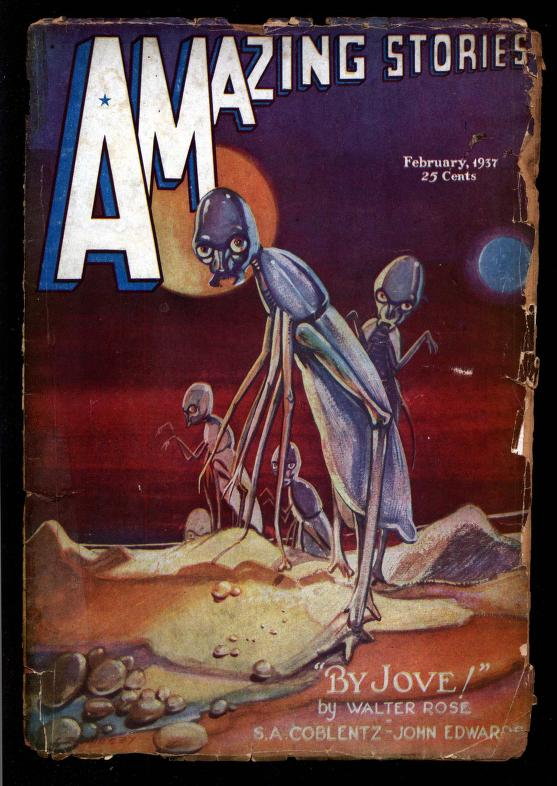

| 2:00p | A Huge Archive of Amazing Stories, the World’s Oldest & Longest-Running Science Fiction Magazine (Since 1926)

If you haven’t heard of Hugo Gernsback, you’ve surely heard of the Hugo Award. Next to the Nebula, it’s the most prestigious of science fiction prizes, bringing together in its ranks of winners such venerable authors as Ursula K. Le Guin, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Heinlein, Neil Gaiman, Isaac Asimov, and just about every other sci-fi and fantasy luminary you could think of. It is indeed fitting that such an honor should be named for Gernsback, the Luxembourgian-American inventor who, in April of 1926, began publishing “the first and longest-running English-language magazine dedicated to what was then not quite yet called ‘science fiction,’” notes University of Virginia’s Andrew Ferguson at The Pulp Magazines Project. Amazing Stories provided an “exclusive outlet” for what Gernsback first called “scientifiction,” a genre he would “for better and for worse, define for the modern era.” You can read and download hundreds of Amazing Stories issues, from the first year of its publication to the last, at the Internet Archive.

Like the extensive list of Hugo Award winners, the back catalog of Amazing Stories encompasses a host of geniuses: Le Guin, Asimov, H.G. Wells, Philip K. Dick, J.G. Ballard, and many hundreds of lesser-known writers. But the magazine “was slow to develop,” writes Scott Van Wynsberghe. Its lurid covers lured some readers in, but its "first two years were dominated by preprinted material,” and Gernsback developed a reputation for financial dodginess and for not paying his writers well or at all. By 1929, he sold the magazine and moved on to other ventures, none of them particularly successful. Amazing Stories soldiered on, under a series of editors and with widely varying readerships until it finally succumbed in 2005, after almost eighty years of publication. But that is no small feat in such an often unpopular field, with a publication, writes Ferguson, that was very often perceived as “garish and nonliterary.”

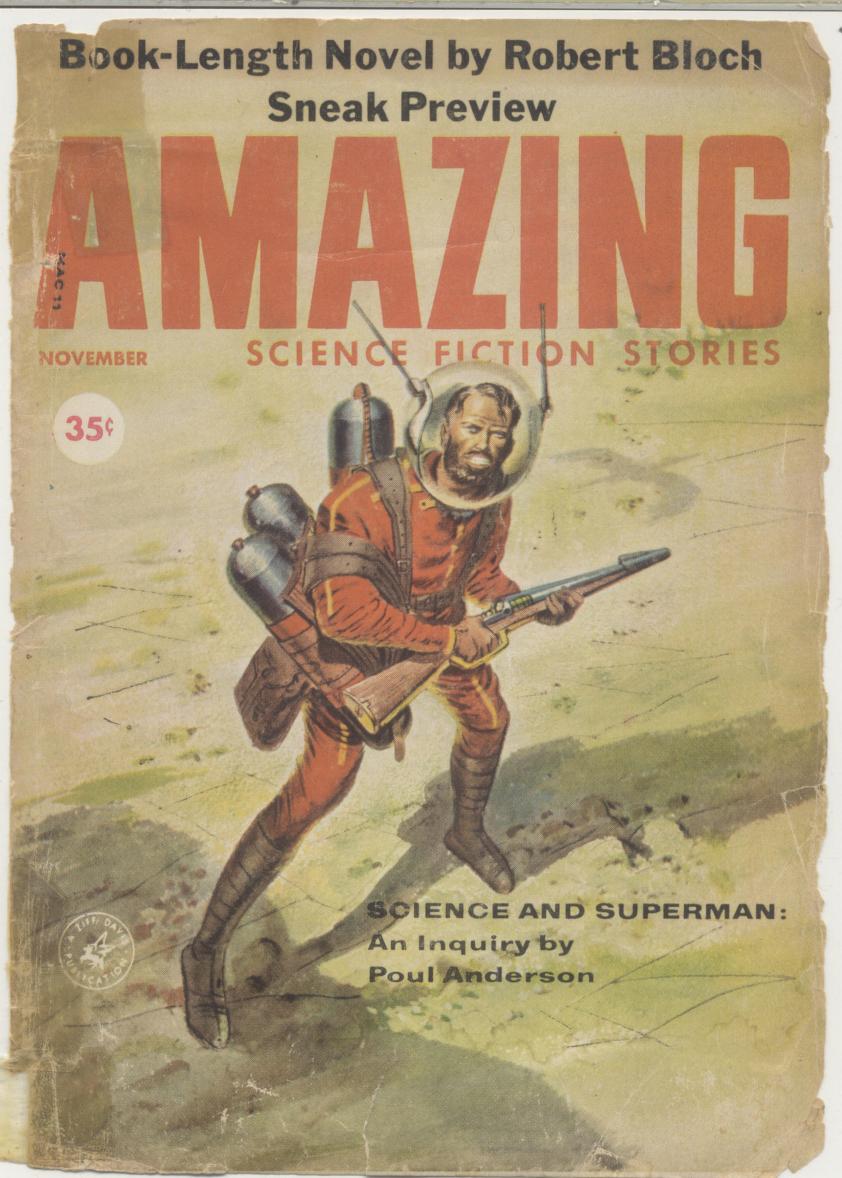

In hindsight, however, we can see Amazing Stories as a sci-fi time capsule and almost essential feature of the genre’s history, even if some of its content tended more toward the young adult adventure story than serious adult fiction. Its flashy covers set the bar for pulp magazines and comic books, especially in its run up to the fifties. After 1955, the year of the first Hugo Award, the magazine reached its peak under the editorship of Cele Goldsmith, who took over in 1959. Gone was much of the eyepopping B-movie imagery of the earlier covers. Amazing Stories acquired a new level of relative polish and sophistication, and published many more “literary” writers, as in the 1959 issue above, which featured a “Book-Length Novel by Robert Bloch.”

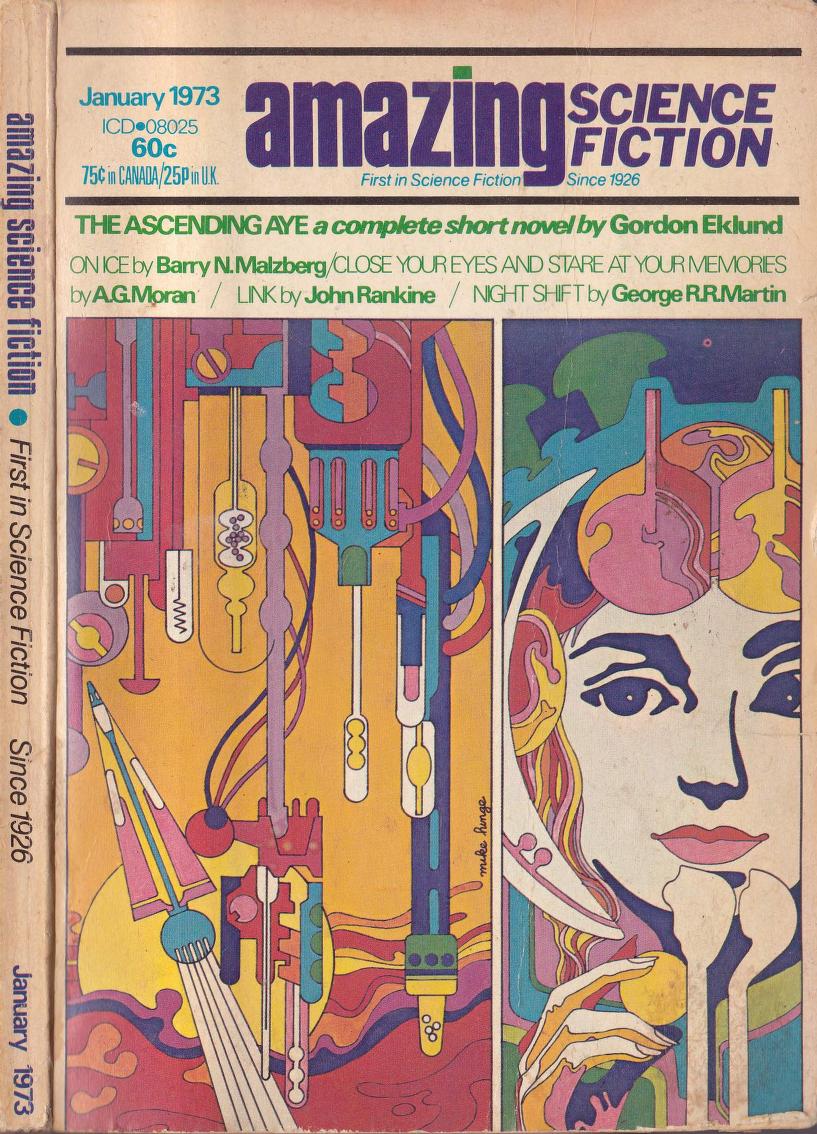

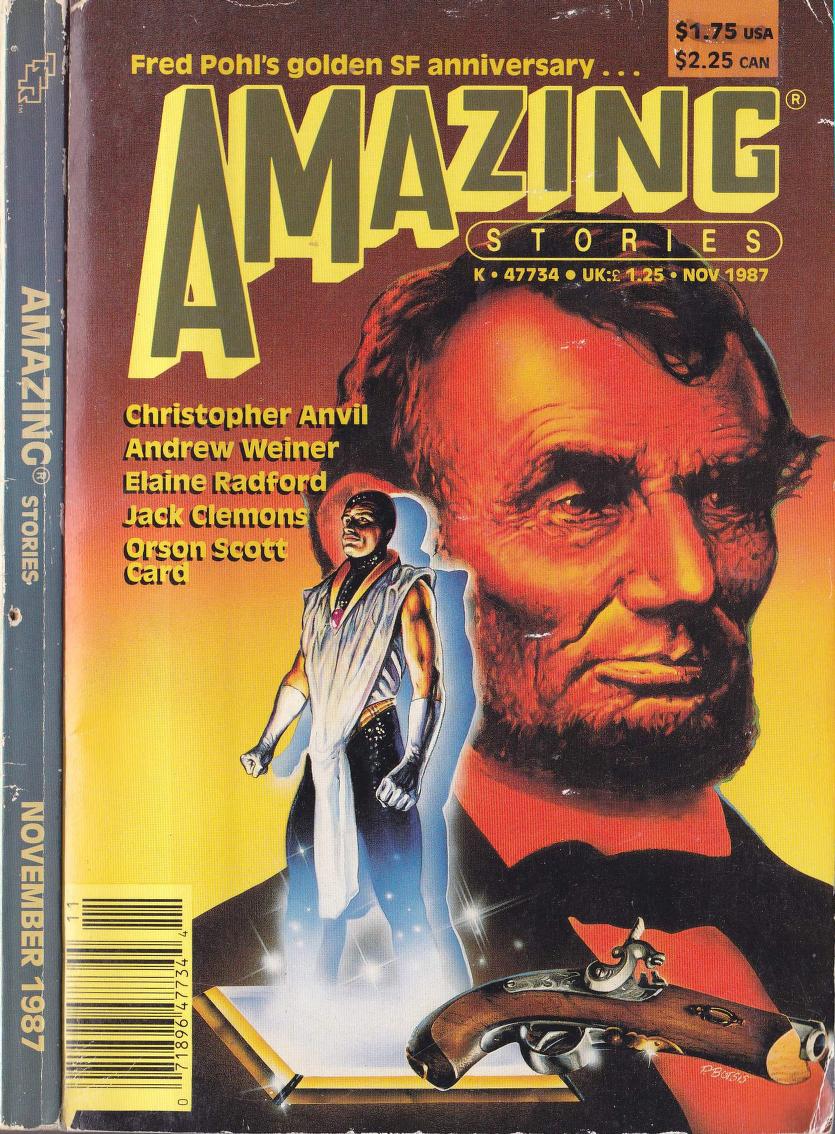

This trend continued into the seventies, as you can see in the issue above, with a “complete short novel by Gordon Eklund” (and early fiction by George R.R. Martin). In 1982, Ferguson writes, Amazing Stories was sold “to Gary Gygax of D&D fame, and would never again regain the prominence it had before.” The magazine largely returned to its pulp roots, with covers that resembled those of supermarket paperbacks. Great writers continued to appear, however. And the magazine remained an important source for new science fiction—though much of it only in hindsight. As for Gernsback, his reputation waned considerably after his death in 1967.

“Within a decade,” writes Van Wynsberghe, “science fiction pundits were debating whether or not he had created a ‘ghetto’ for hack writers.” In 1986, novelist Brian Aldiss called Gernsback “one of the worst disasters ever to hit the science fiction field.” His 1911 novel, the ludicrously named Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660 is considered “one of the worst science fiction novels in history,” writes Matthew Lasar. It may seem odd that the Oscar of the sci-fi world should be named for such a reviled figure. And yet, despite his pronounced lack of literary ability, Gernsback was a visionary. As a futurist, he made some startlingly accurate predictions, along with some not-so-accurate ones. As for his significant contribution to a new form of writing, writes Lasar, “It was in Amazing Stories that Gernsback first tried to nail down the science fiction idea.” As Ray Bradbury supposedly said, “Gernsback made us fall in love with the future.” Enter the Amazing Stories Internet Archive here. Related Content: Omni, the Iconic Sci-Fi Magazine, Now Digitized in High-Resolution and Available Online Free: 355 Issues of Galaxy, the Groundbreaking 1950s Science Fiction Magazine Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

A Huge Archive of Amazing Stories, the World’s Oldest & Longest-Running Science Fiction Magazine (Since 1926) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:04p | Infinite Escher: A High-Tech Tribute to M.C. Escher, Featuring Sean Lennon, Nam June Paik & Ryuichi Sakamoto (1990) When television appeared in Japan in the 1950s, most people in that still-poor country could only satisfy their curiosity about it by watching the display models in store windows. But by the 1980s, the Japanese had become not just astonishingly rich but world leaders in technology as well. It took something special to make Tokyoites stop on the streets of Akihabara, the city's go-to district for high technology, but stop they did in 1990 when, in the windows of Sony Town, appeared Infinite Escher. Produced by Sony HDVS Soft Center as a showcase for the company's brand new high-definition video technology, this short film caused passersby, according to the video description, to "gasp in amazement at the clarity and sharp crisp focus of the picture." Running seven and a half minutes, it tells the story of a bespectacled New York City teenager (played by a young Sean Lennon, son of John Lennon and Yoko Ono) who steps off the school bus one afternoon to find M.C. Escher-style visual motifs in the urban landscape all around him: a jigsaw puzzle piece-shaped curbside puddle, a transparent geometrically patterned basketball. When he goes home to sketch a few artistic-mathematical ideas of his own, he looks into an awfully familiar-looking reflecting sphere and gets sucked into a completely Escherian realm. This sequence demonstrates not just the look of Sony's high-definition video, but the then-state-of-the-art techniques for dropping real-life characters into computer-generated settings and vice versa. In addition to the visions of the Dutch graphic designer who not just imagined but rendered the impossible, Sony also brought in two of the other powerful creative minds, Japanese musician Ryuichi Sakamoto to create the score and Korean video artist Nam June Paik to do the art direction. Watching Infinite Escher today may first underscore just how far high-definition video and computer graphics have come over the past 27 years, but it ultimately shows another example of how Escher's visions, even after the artist's death in 1972, have remained so compelling that each era — with its own technological, cultural, and aesthetic trends — pays its own kind of tribute to them. Related Content: Watch M.C. Escher Make His Final Artistic Creation in the 1971 Documentary Adventures in Perception Metamorphose: 1999 Documentary Reveals the Life and Work of Artist M.C. Escher Inspirations: A Short Film Celebrating the Mathematical Art of M.C. Escher David Bowie Sings in a Wonderful M.C. Escher-Inspired Set in Jim Henson’s Labyrinth 62 Psychedelic Classics: A Free Playlist Created by Sean Lennon Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Infinite Escher: A High-Tech Tribute to M.C. Escher, Featuring Sean Lennon, Nam June Paik & Ryuichi Sakamoto (1990) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/07/19 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |