[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, July 24th, 2017

| Time | Event |

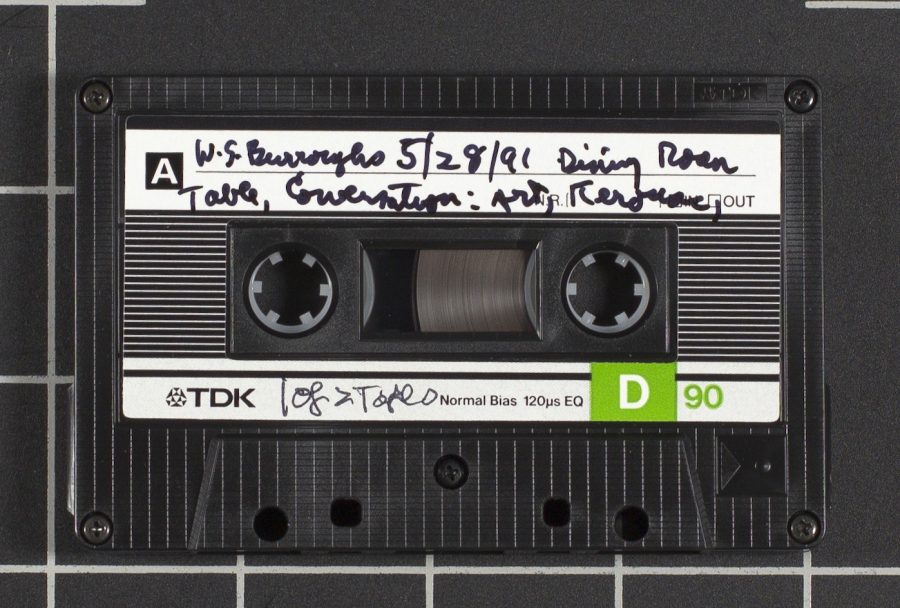

| 8:24a | 2,000+ Cassettes from the Allen Ginsberg Audio Collection Now Streaming Online

Last month Colin Marshall gave you the scoop on Stanford University's digitization of Allen Ginsberg's "Howl," a project that takes you inside the making of the iconic 1955 poem. As a quick follow up, it's worth mentioning this: Stanford has also just put online over 2,000 Ginsberg audio cassette recordings, giving you access to "a staggering amount of primary source material associated with the Beat Generation" and its most acclaimed poet. For a quick taste of what's in the archive, Stanford Libraries points you to an afternoon breakfast table conversation between Ginsberg and another legendary Beat figure, William S. Burroughs. But you can rummage/search through the whole collection and find your own favorite recordings here. via Stanford Libraries and Austin Kleon's newsletter (which you should subscribe to here) Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: The First Recording of Allen Ginsberg Reading “Howl” (1956) Allen Ginsberg Reads His Famously Censored Beat Poem, "Howl" (1959) James Franco Reads a Dreamily Animated Version of Allen Ginsberg’s Epic Poem ‘Howl’ Allen Ginsberg’s “Celestial Homework”: A Reading List for His Class “Literary History of the Beats” Allen Ginsberg Recordings Brought to the Digital Age. Listen to Eight Full Tracks for Free Allen Ginsberg’s Handwritten Poem For Bernie Sanders, “Burlington Snow” (1986) 2,000+ Cassettes from the Allen Ginsberg Audio Collection Now Streaming Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | Marshall McLuhan Predicts That Electronic Media Will Displace the Book & Create Sweeping Changes in Our Everyday Lives (1960) "The electronic media haven't wiped out the book: it's read, used, and wanted, perhaps more than ever. But the role of the book has changed. It's no longer alone. It no longer has sole charge of our outlook, nor of our sensibilities." As familiar as those words may sound, they don't come from one of the think pieces on the changing media landscape now published each and every day. They come from the mouth of midcentury CBC television host John O'Leary, introducing an interview with Marshall McLuhan more than half a century ago. McLuhan, one of the most idiosyncratic and wide-ranging thinkers of the twentieth century, would go on to become world famous (to the point of making a cameo in Woody Allen's Annie Hall) as a prophetic media theorist. He saw clearer than many how the introduction of mass media like radio and television had changed us, and spoke with more confidence than most about how the media to come would change us. He understood what he understood about these processes in no small part because he'd learned their history, going all the way back to the development of writing itself. Writing, in McLuhan's telling, changed the way we thought, which changed the way we organized our societies, which changed the way we perceived things, which changed the way we interact. All of that holds truer for the printing press, and even truer still for television. He told the story in his book The Gutenberg Galaxy, which he was working on at the time of this interview in May of 1960, and which would introduce the term "global village" to its readers, and which would crystallize much of what he talked about in this broadcast. Electronic media, in his view, "have made our world into a single unit." With this "continually sounding tribal drum" in place, "everybody gets the message all the time: a princess gets married in England, and 'boom, boom, boom' go the drums. We all hear about it. An earthquake in North Africa, a Hollywood star gets drunk, away go the drums again." The consequence? "We're re-tribalizing. Involuntarily, we're getting rid of individualism." Where "just as books and their private point of view are being replaced by the new media, so the concepts which underlie our actions, our social lives, are changing." No longer concerned with "finding our own individual way," we instead obsess over "what the group knows, feeling as it does, acting 'with it,' not apart from it." Though McLuhan died in 1980, long before the appearance of the modern internet, many of his readers have seen recent technological developments validate his notion of the global village — and his view of its perils as well as its benefits — more and more with time. At this point in history, mankind can seem less united than ever than ever, possibly because technology now allows us to join any number of global "tribes." But don't we feel more pressure than ever to know just what those tribes know and feel just what they feel? No wonder so many of those pieces that cross our news feeds today still reference McLuhan and his predictions. Just this past weekend, Quartz's Lila MacLellan did so in arguing that our media, "while global in reach, has come to be essentially controlled by businesses that use data and cognitive science to keep us spellbound and loyal based on our own tastes, fueling the relentless rise of hyper-personalization" as "deep-learning powered services promise to become even better custom-content tailors, limiting what individuals and groups are exposed to even as the universe of products and sources of information expands." Long live the individual, the individual is dead: step back, and it all looks like one of those contradictions McLuhan could have delivered as a resonant sound bite indeed. Related Content: Has Technology Changed Us?: BBC Animations Answer the Question with the Help of Marshall McLuhan McLuhan Said “The Medium Is The Message”; Two Pieces Of Media Decode the Famous Phrase The Visionary Thought of Marshall McLuhan, Introduced and Demystified by Tom Wolfe Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Marshall McLuhan Predicts That Electronic Media Will Displace the Book & Create Sweeping Changes in Our Everyday Lives (1960) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | The Strange Story of Wonder Woman’s Creator William Moulton Marston: Polyamorous Feminist, Psychologist & Inventor of the Lie Detector Most young male fans from my generation failed to appreciate the gender imbalance in comic books. After all, what were the X-Men without powerful X-women Storm, Rogue, and, maybe the most powerful mutant of all, Jean Grey? Indie comics like Love and Rockets revolved around strong female characters, and if the legacy golden age Marvel and DC titles were nearly all about Great Men, well... just look at the time they came from. We shrugged it off, and also failed to appreciate how the hypersexualization of women in comics made many of the women around us uncomfortable and hyperannoyed. Had we been curious enough to look, however, we would have found that golden age comics weren’t just innocent “products of their time”—they reflected a collective will, just as did the comics of our time. And the character who first challenged golden age attitudes about women—Wonder Woman, created in 1941—began her career as perhaps one of the kinkiest superheroes in mainstream comic books. What’s more, she was created by a psychologist William Moulton Marston, who first published under a pseudonym, due in part to his unconventional personal life. Marston, writes NPR, “had a wife—and a mistress. He fathered children with both of them, and they all secretly lived together in Rye, N.Y.” The other woman in Marston’s polyamorous threesome, one of his former students, happened to be the niece of Margaret Sanger, and Marston just happened to be the creator of the lie detector. The details of his life are as odd and prurient now as they were to readers in the 1940s—partly an index of how little some things have changed. And now that Marston’s creation has finally received her blockbuster due, his story seems ripe for the Hollywood telling. Such it has received, it appears, in Professor Marston & the Wonder Women, the upcoming biopic by Angela Robinson. It’s unfair to judge a film by its trailer, but in the clips above we see much more of Marston’s dual romance than we do of the invention of his famous heroine.

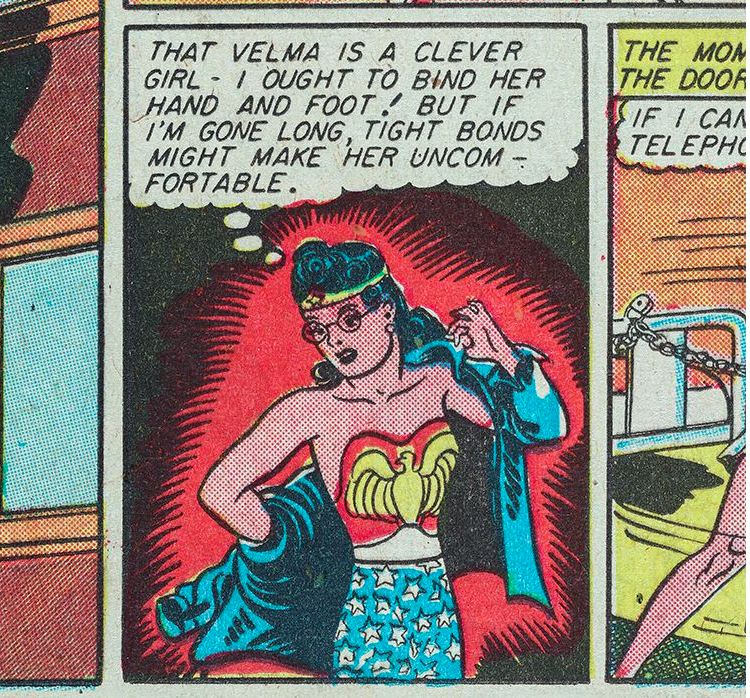

Yet as political historian Jill Lepore tells it, the cultural history of Wonder Woman is as fascinating as her creator’s personal life, though it may be impossible to fully separate the two. A press release accompanying Wonder Woman’s debut explained that Marston aimed “to set up a standard among children and young people of strong, free, courageous womanhood; to combat the idea that women are inferior to men, and to inspire girls to self-confidence in athletics, occupations and professions monopolized by men.” It went on to express Marston’s view that “the only hope for civilization is the greater freedom, development and equality of women in all fields of human activity.” The language sounds like that of many a modern-day NGO, not a World War II-era popular entertainment. But Marston would go further, saying, “Frankly, Wonder Woman is the psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world.” His interest in domineering women and S&M drove the early stories, which are full of bondage imagery. “There are a lot of people who get very upset at what Marston was doing...,” Lepore told Terry Gross on Fresh Air. “’Is this a feminist project that’s supposed to help girls decide to go to college and have careers, or is this just like soft porn?’” As Marston understood it, the latter question could be asked of most comics.

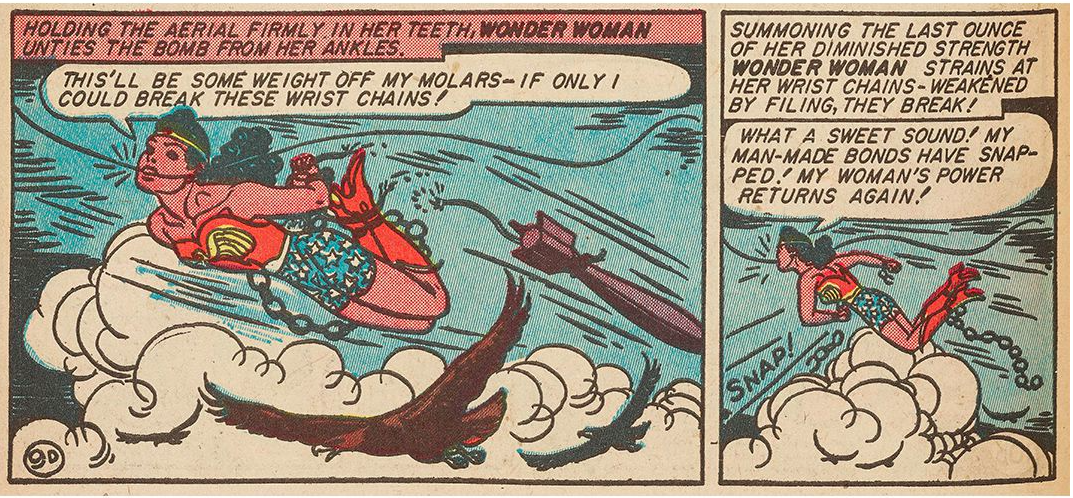

When writer Olive Richard—pen name of Marston’s mistress Olive Byrne—asked him in an interview for Family Circle whether some comics weren’t “full of torture, kidnapping, sadism, and other cruel business,” he replied, “Unfortunately, that is true. But “the reader’s wish is to save the girl, not to see her suffer.” Marston created a “girl”—or rather a superhuman Amazonian princess—who saved herself and others. “One of the things that’s a defining element of Wonder Woman,” says Lepore, “is that if a man binds her in chains, she loses all of her Amazonian strength. So in almost every episode of the early comics, the ones that Marston wrote... she’s chained up or she’s roped up.” She has to break free, he would say, “in order to signify her emancipation from men.” She does her share of roping others up as well, with her lasso of truth and other means.

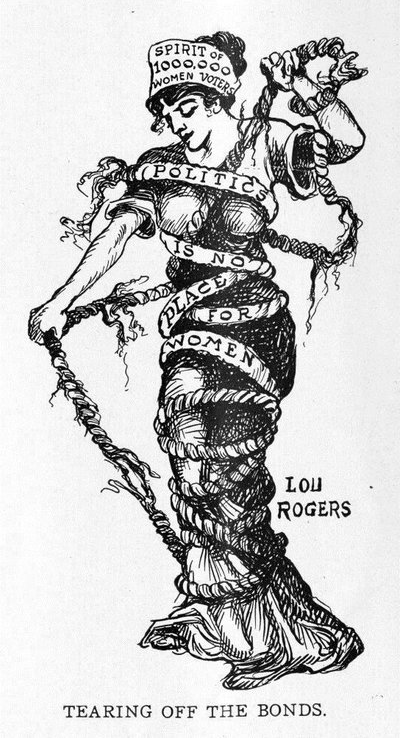

The seemingly clear bondage references in all those chains also had clear political significance, Lepore explains. During the fight for suffrage, women would chain themselves to government buildings. In parades, suffragists "would march in chains—they imported that iconography from the abolitionist campaigns of the 19th century that women had been involved in... Chains became a really important symbol,” as in the 1912 drawing below by Lou Rogers. Wonder Woman’s mythological origins also had deeper signification than the male fantasy of a powerful race of well-armed dominatrices. Her story, writes Lepore at The New Yorker, “comes straight out of feminist utopian fiction” and the fascination many feminists had with anthropologists' speculation about an Amazonian matriarchy.

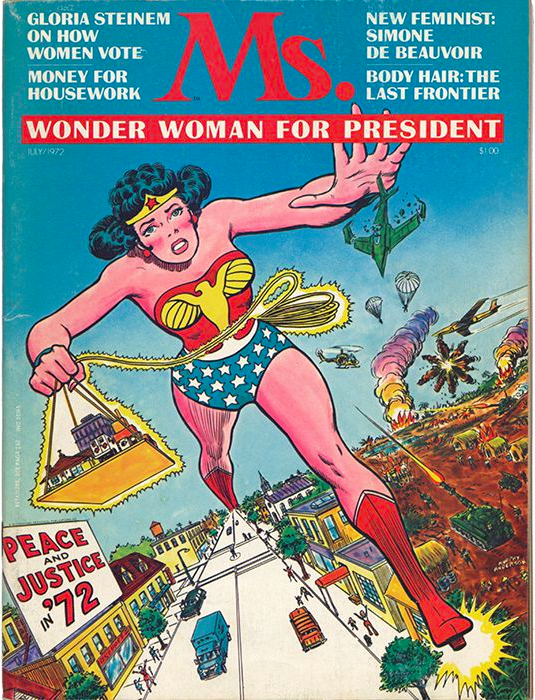

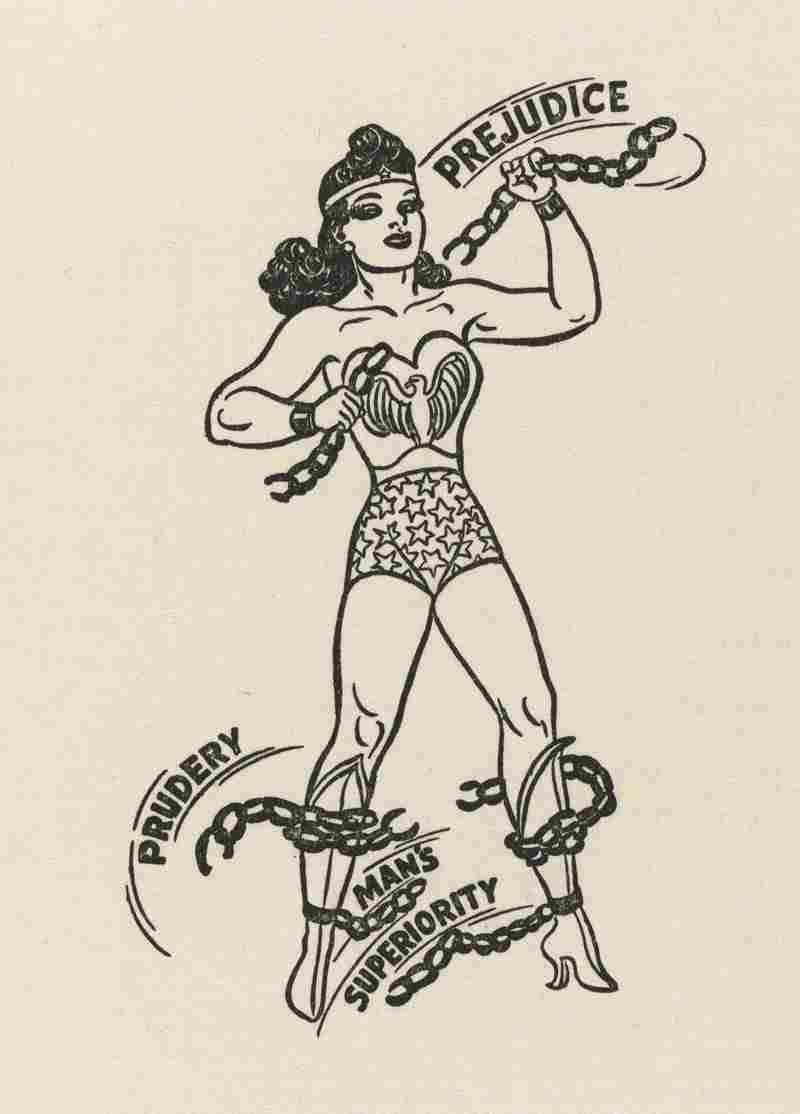

The combination of feminist symbols have made the character a redoubtable icon for every generation of activists—as in her appearance on 1972 cover of Ms. magazine, further up, an issue headlined by Gloria Steinem and Simone de Beauvoir. Marston translated the feminist ideas of the suffrage movement, and of women like Margaret Sanger, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, his wife, lawyer Elizabeth Holloway Marston, and his mistress Olive Byrne, into a powerful, long-revered superhero. He also translated his own ideas of what Havelock Ellis called “the erotic rights of women.” Marston's version of Wonder Woman (he stopped writing the comic in 1947) had as much agency—sexual and otherwise—as any male character of the time. (See her breaking the bonds of “Prejudice,” “Prudery,” and “Man’s Superiority” in a drawing, below, from Marston’s 1943 article “Why 100,000 Americans Read Comics.”) The character was undoubtedly kinky, a quality that largely disappeared from later iterations. But she was not created, as were so many women in comics in the following decades, as an object of teenage lust, but as a radically liberated feminist hero. Read more about Marston in Lepore’s essays at Smithsonian and The New Yorker and in her book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman.

Related Content: Download Over 22,000 Golden & Silver Age Comic Books from the Comic Book Plus Archive Free Comic Books Turns Kids Onto Physics: Start With the Adventures of Nikola Tesla Take a Free Online Course on Making Comic Books, Compliments of the California College of the Arts Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Strange Story of Wonder Woman’s Creator William Moulton Marston: Polyamorous Feminist, Psychologist & Inventor of the Lie Detector is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:00p | Watch Iggy Pop & Debbie Harry Sing a Swelligant Version of Cole Porter’s “Did You Evah,” All to Raise Money for AIDS Research (1990)

Quick survey: Who’s best fit to get at the heart of Cole Porter? The suave sophisticate who was born in a tux, martini glass clutched in his infant fist? Or punk royalty? “Well, Did You Evah!” from the 1939 Broadway musical DuBarry Was a Lady, is the brattier cousin of such Porter hits as “You’re the Top” and “Let’s Do It.” Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby performed a boozy cover of it for the 1956 film High Society, but for my money, the definitive version is one Iggy Pop and Debbie Harry recorded for a Cole Porter themed AIDS benefit album, Red Hot + Blue. Some Porter classics–“Every Time We Say Goodbye,” “So In Love”–demand sincerity. This one calls for a strong dose of the opposite, which Pop and Harry deliver, both vocally and in the barnstorming music video above. They’re dangerous, funny, and anything but canned, weaving through rat-glammy 1980s New York in thrift store finery, with side trips to a cemetery and a farm where Pop smooches a goat. As Alex Cox, who brought further punk pedigree to the project as the director of Sid and Nancy and Repo Man told Spin: "Iggy had always wanted to make a video with animals and Debbie had always wanted to publicly burn lingerie so I let them." They also filled Pop’s palms with stigmata and ants, and swapped Porter’s champagne for a case of generic dog food. There are a few minor tweaks to the lyrics (“What cocks!”) and the stars inject the patter with a gleefully louche downtown sensibility. Mars rises behind the Twin Towers, for a swelligantly off-beat package that raised a lot of money for AIDS research and awareness. Other gems from the project: "It's All Right with Me" performed by Tom Waits, directed by Jim Jarmusch "Night and Day" performed by U2, directed by Wim Wenders "Don't Fence Me In" performed and directed by David Byrne Related Content: Iggy Pop Sings Edith Piaf’s “La Vie En Rose” in an Artfully Animated Video Tom Waits For No One: Watch the Pioneering Animated Tom Waits Music Video from 1979 Bill Murray Reads Great Poetry by Billy Collins, Cole Porter, and Sarah Manguso Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Watch Iggy Pop & Debbie Harry Sing a Swelligant Version of Cole Porter’s “Did You Evah,” All to Raise Money for AIDS Research (1990) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/07/24 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |