[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, August 2nd, 2017

| Time | Event |

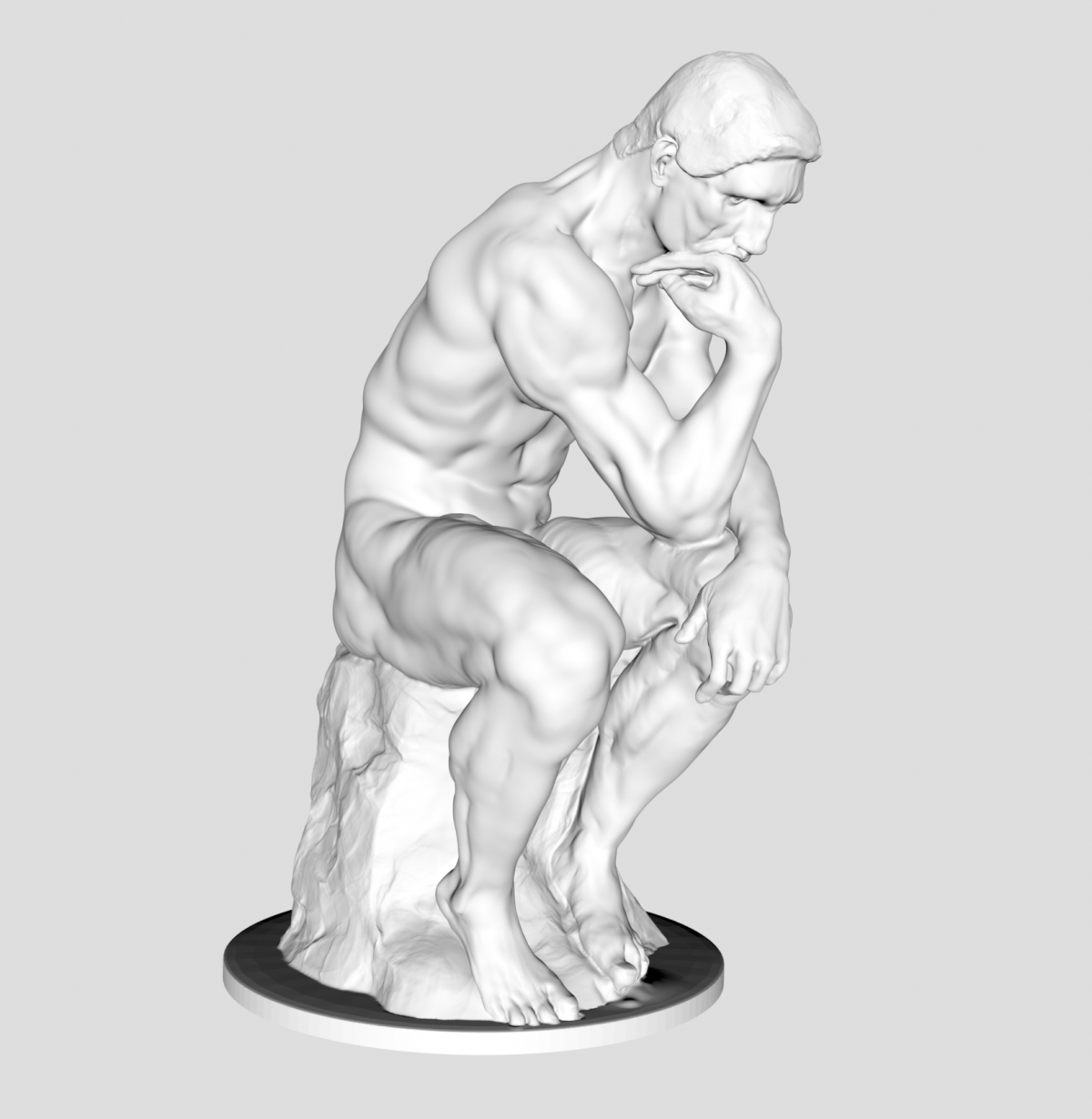

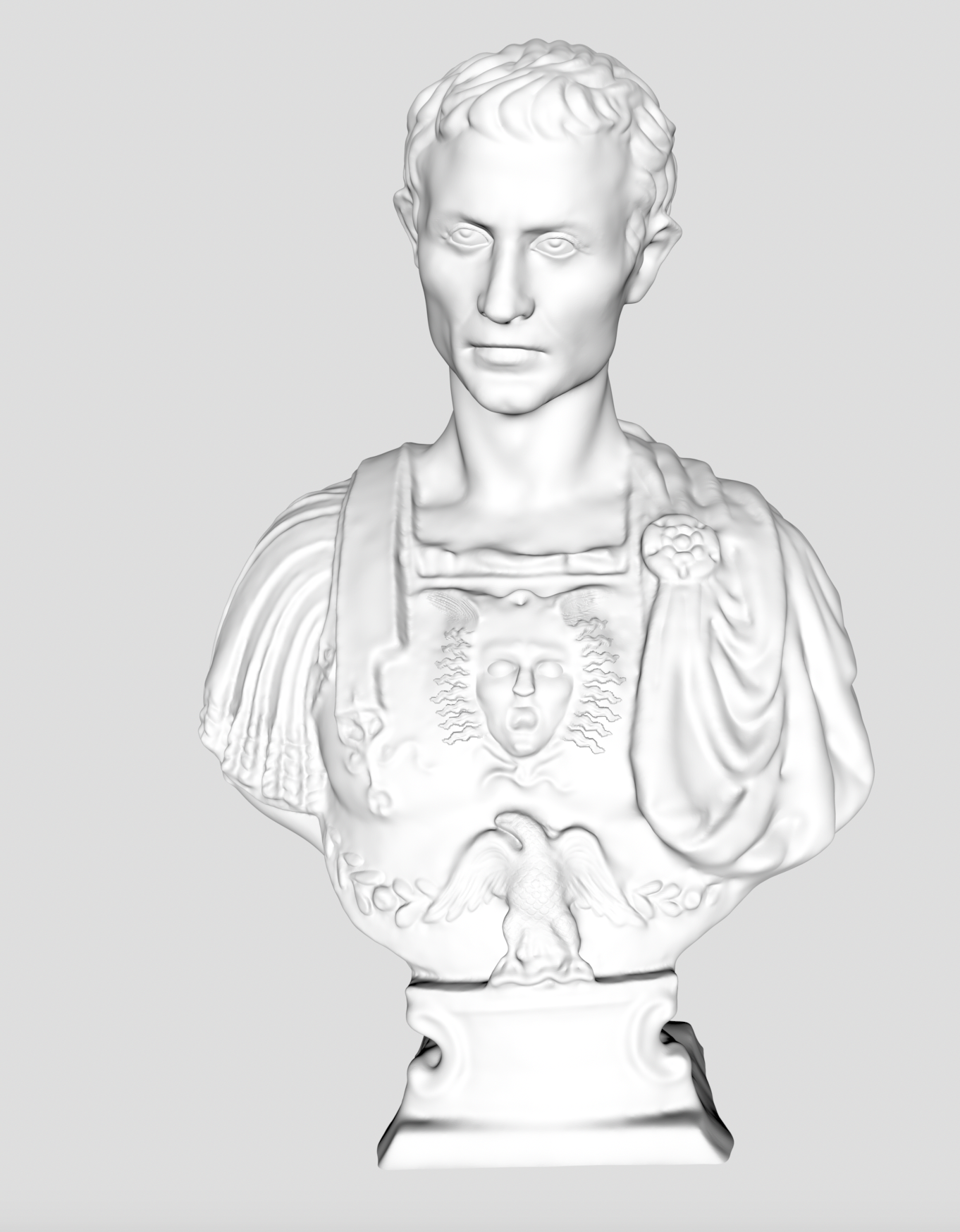

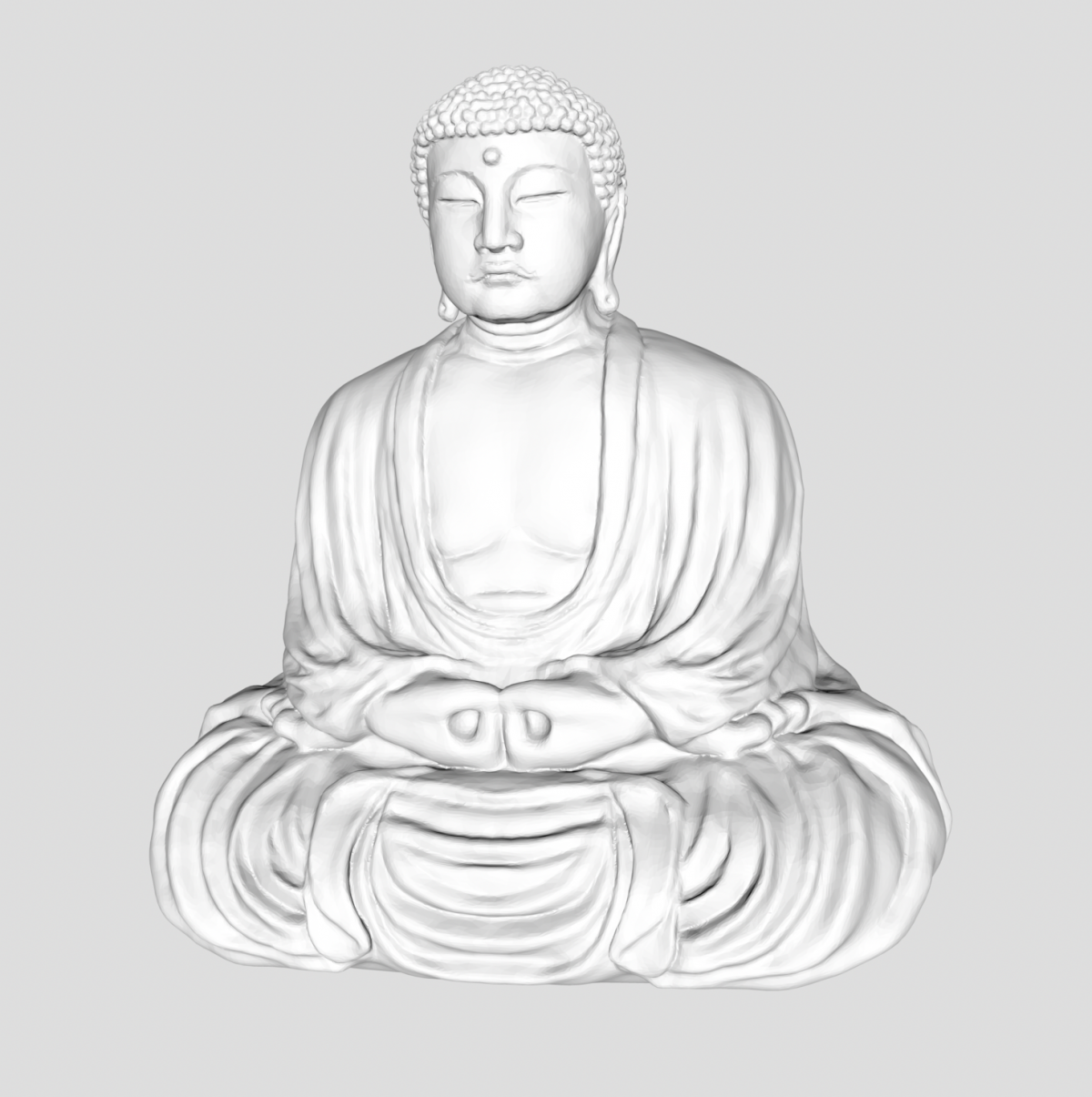

| 8:00a | 3D Scans of 7,500 Famous Sculptures, Statues & Artworks: Download & 3D Print Rodin’s Thinker, Michelangelo’s David & More

Last week we featured the British Museum's archive of downloadable 3D models of over 200 richly historical objects in their collection, perhaps most notably the Rosetta Stone. But back in 2015, before that mighty cultural institution put online in 3D the most important linguistic artifact of them all, a project called Scan the World created a model of it during an unofficial community "scanathon," and it remains freely available to all who would, for example, like to 3D print a Rosetta Stone of their very own.

Or perhaps you'd prefer to run off your own copy of a world-famous sculpture like ancient Egyptian court sculptor Thutmose's bust of Nefertiti or Auguste Rodin's The Thinker, both of whose 3D models you can find on Scan the World's archive at My Mini Factory. There the organization, "comprised of a vast community of 3D scanning and 3D printing enthusiasts," has amassed a collection of 7,834 3D models and counting, all toward their mission " to archive the world’s sculptures, statues, artworks and any other objects of cultural significance using 3D scanning technologies to produce content suitable for 3D printing."

Scan the World hasn't limited its mandate to just artifacts and artworks kept in museums: among its models you'll also find large scale pieces of public sculpture like the Statue of Liberty and even beloved buildings like Big Ben. This conjures up the tantalizing vision of each of us one day becoming empowered to 3D-print our very own London, complete with not just a British Museum but all the objects, each of which tells part of humanity's story, inside it.

As much of a technological marvel as it may represent, printing out a Venus de Milo or a David or a Leaning Tower of Pisa or a Moai head at home can't, of course, compare to making the trip to see the genuine article, especially with the kind of 3D printers now available to consumers. But as recent technological history has shown us, the most amazing developments tend to come out of the decentralized efforts of countless enthusiasts — just the kind of community powering Scan the World. The great achievements of the future have to start somewhere, and they might as well start by paying tribute to the greatest achievements of the past. Related Content: The Complete History of the World (and Human Creativity) in 100 Objects Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. 3D Scans of 7,500 Famous Sculptures, Statues & Artworks: Download & 3D Print Rodin’s Thinker, Michelangelo’s David & More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

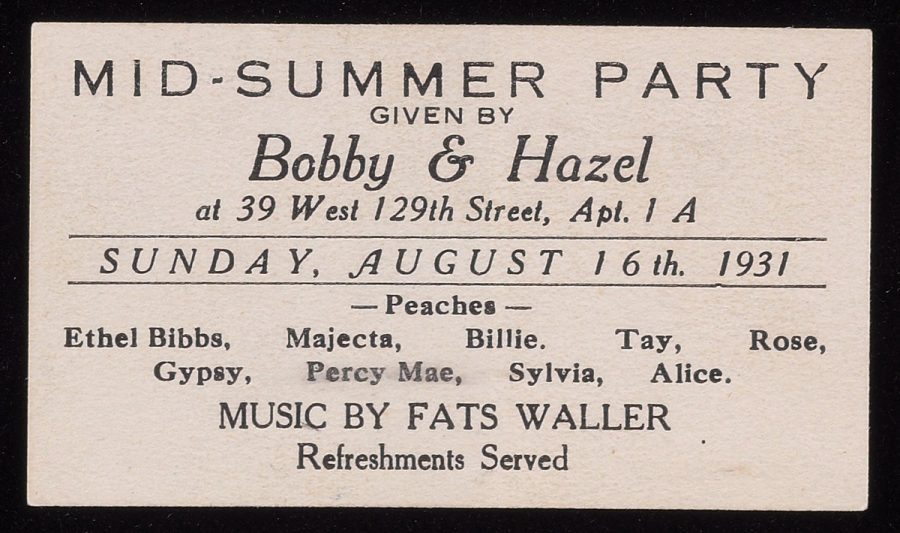

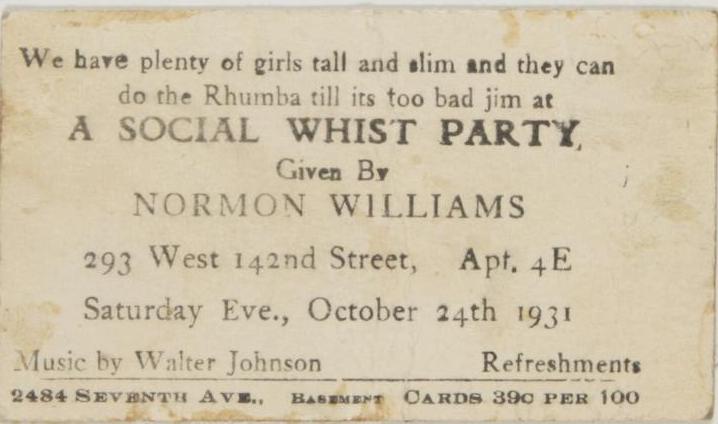

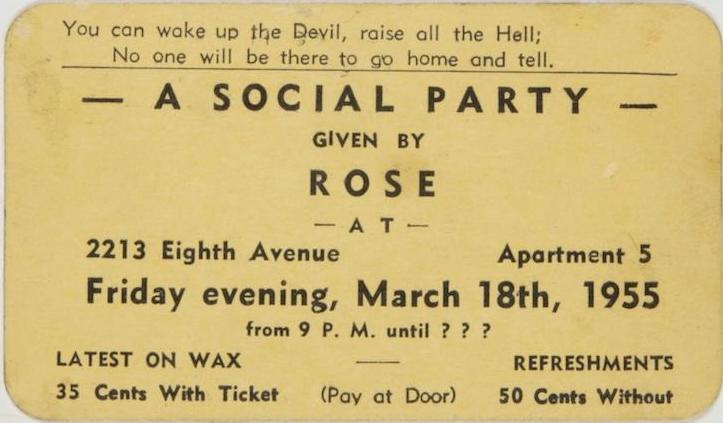

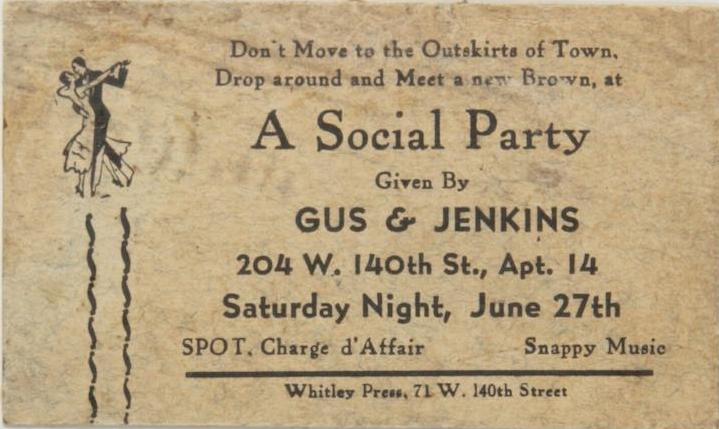

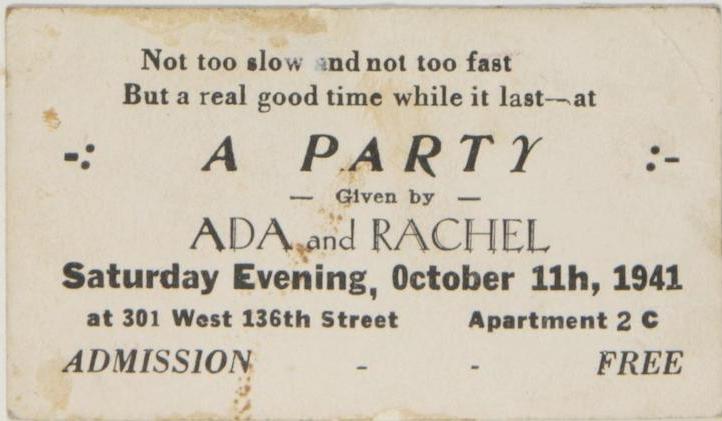

| 11:00a | Langston Hughes’ Collection of Rent Party Ads: The Harlem Renaissance Tradition of Playing Gigs to Keep Roofs Over Heads

Both communities of color and communities of artists have had to take care of each other in the U.S., creating systems of support where the dominant culture fosters neglect and deprivation. In the early twentieth century, at the nexus of these two often overlapping communities, we meet Langston Hughes and the artists, poets, and musicians of the Harlem Renaissance. Hughes’ brilliantly compressed 1951 poem “Harlem” speaks of the simmering frustration among a weary people. But while its startling final line hints grimly at social unrest, it also looks back to the explosion of creativity in the storied New York City neighborhood during the Great Depression.

Hughes had grown reflective in the 50s, returning to the origins of jazz and blues and the history of Harlem in Montage of a Dream Deferred. The strained hopes and hardships he had eloquently documented in the 20s and 30s remained largely the same post-World War II, and one of the key features of Depression-era Harlem had returned; Rent parties, the wild shindigs held in private apartments to help their residents avoid eviction, were back in fashion, Hughes wrote in the Chicago Defender in 1957. “Maybe it is inflation today and the high cost of living that is causing the return of the pay-at-the-door and buy-your-own-refreshments parties,” he said. He also noted that the new parties weren’t as much fun.

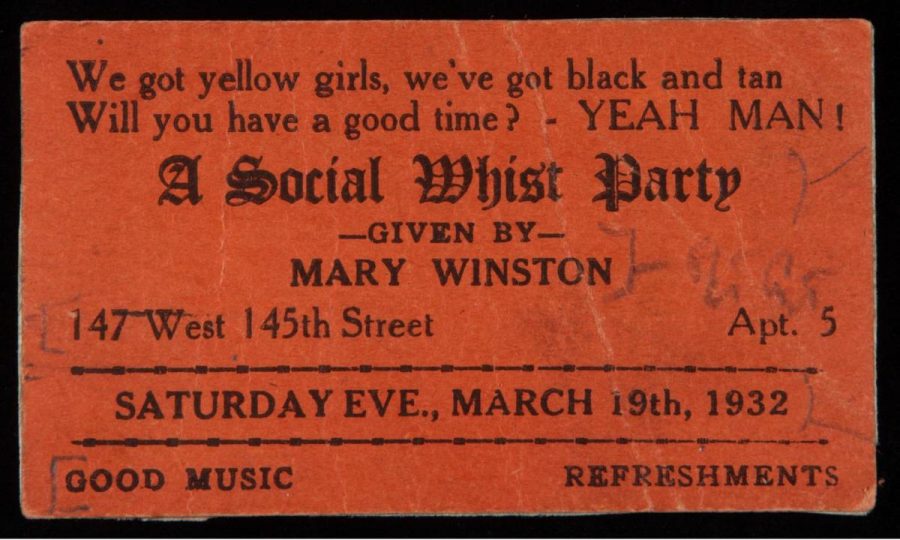

But how could they be? Depression-era rent parties were legendary. They “impacted the growth of Swing and Blues dancing,” writes dance teacher Jered Morin, “like few other periods.” As Hughes commented, “the Saturday night rent parties that I attended were often more amusing than any night club, in small apartments where God-knows-who lived.” Famous artists met and rubbed elbows, musicians formed impromptu jams and invented new styles, working class people who couldn’t afford a night out got to put on their best clothes and cut loose to the latest music. Hughes was fascinated, and as a writer, he was also quite taken by the quirky cards used to advertise the parties. “When I first came to Harlem,” he said, “as a poet I was intrigued by the little rhymes at the top of most House Rent Party cards, so I saved them. Now I have quite a collection.”

The cards you see here come from Hughes’ personal collection, held with his papers at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Many of these date from the 40s and 50s, but they all draw their inspiration from the Harlem Renaissance period, when the phenomenon of jazz-infused rent parties exploded. “Sandra L. West points out that black tenants in Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s faced discriminatory rental rates,” notes Rebecca Onion at Slate. “That, along with the generally lower salaries for black workers, created a situation in which many people were short of rent money. These parties were originally meant to bridge that gap.” A 1938 Federal Writers Project account put it plainly: Harlem “was a typical slum and tenement area little different from many others in New York except for the fact that in Harlem rents were higher; always have been, in fact, since the great war-time migratory influx of colored labor.”

Tenants took it in stride, drawing on two longstanding community traditions to make ends meet: the church fundraiser and the Saturday night fish fry. But rent parties could be raucous affairs. Guests typically paid a few cents to enter, and extra for food cooked by the host. Apartments filled far beyond capacity, and alcohol—illegal from 1919 to 1933—flowed freely. Gambling and prostitution frequently made an appearance. And the competition could be fierce. The Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance writes that in their heyday, “as many as twelve parties in a single block and five in an apartment building, simultaneously, were not uncommon.” Rent parties "essentially amounted to a kind of grassroots social welfare," though the atmosphere could be "far more sordid than the average neighborhood block party." Many upright citizens who disapproved of jazz, gambling, and booze turned up their noses and tried to ignore the parties.

In order to entice party-goers and distinguish themselves, writes Onion, “the cards name the kind of musical entertainment attendees could expect using lyrics from popular songs or made-up rhyming verse as slogans.” They also “used euphemisms to name the parties’ purpose,” calling them “Social Whist Party” or “Social Party,” while also slyly hinting at rowdier entertainments. The new rent parties may not have lived up to Hughes’ memories of jazz-age shindigs, perhaps because, in some cases, live musicians had been replaced by record players. But the new cards, he wrote “are just as amusing as the old ones.” Related Content: Langston Hughes Presents the History of Jazz in an Illustrated Children’s Book (1955) Watch Langston Hughes Read Poetry from His First Collection, The Weary Blues (1958) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Langston Hughes’ Collection of Rent Party Ads: The Harlem Renaissance Tradition of Playing Gigs to Keep Roofs Over Heads is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Hear Patti Smith Read the Poetry that Would Become Horses: A Reading of 14 Poems at Columbia University, 1975 Note: The first poem and others contain some offensive language. In the context of the radical socio-political change of 1975, Patti Smith announced herself to the world with Horses, “the first real full-length hint of the artistic ferment taking place in the mid-‘70s at the juncture of Bowery and Bleecker,” writes Mac Randall. Though born in an insular downtown milieu, Smith’s view was vast, conducting the poetry of the past—of Rimbaud, the Beats, and rock and roll—into an uncertain future, through the nascent medium of punk rock. The album is “closely associated with the beginning of something,” and yet is “so concerned with endings": the loss of Jimi Hendrix (at whose studio Smith recorded), and of “other departed counterculture heroes like Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin and Brian Jones.” In a way, Smith’s voice defines the pivotal moment in which it arrived: anticipating an anxious age of austerity and women's liberation; mourning the loss of 60s idealism and the promise of racial equity. She was a female artist fully unconstrained by patriarchal expectations, with complete authority over her vision. “My people were trying to forge a new bridge between the people we had lost and learned from and the future,” she recently remarked. In her “fabulously grand” way, she told The Guardian’s Simon Hattenstone in 2013, “I felt in the center, not quite the old generation, not quite the new generation. I felt like the human bridge.” Smith was no naïf when she made Horses, but a confident artist who, at 29, had worked in theater with her lately-departed friend Sam Shepard, become her famous lover Robert Mapplethorpe’s favorite subject, joined the St. Mark’s Poetry Project, and published two collections of verse. She thought of herself as a poet who “got sidetracked” by music. “When I was young,” Smith says, “all I wanted was to write books and be an artist.” But poetry was always central to her work; Horses, she says, “evolved organically” from her first poetry reading, four years earlier, at St. Mark's Church, alongside Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and other luminaries. Above, you can hear her discuss that attention-grabbing first reading, and at the top of the post, listen to Smith at Columbia University in 1975, reading the poems that developed that year into the songs on Horses, including her 1971 “Oath,” which begins with a variation on Horses’ opening sneer, “Christ died for somebody’s sins, but not mine.” Be warned the first poem she reads contains offensive language, as do many others. No one should be shocked by this. But some who only know Smith as a singer may be surprised by her masterful literary voice and wicked sense of humor. She has always been an elegist, mourning her cultural heroes, most of whom died young, as well as a tragic string of personal losses. “When I started working with the material that became Horses,” she remembers, “a lot of our great voices had died.” But her intent went beyond elegy, beyond a maudlin appropriation of fading 60s heroes. Smith had a “mission,” she says, of “forming a cultural voice through rock’n’roll that incorporated sex and art and poetry and performance and revolution.” It sounds grandiose, but it’s a mission she’s largely fulfilled. At the center of her project is poetry as performance, as a means of entertaining, shocking, and seducing an audience. The reading at the top is an especially faithful record of her fearless onstage persona. Find more poetry readings in our collection, 900 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free. Related Content: Hear Patti Smith Read 12 Poems From Seventh Heaven, Her First Collection (1972) Watch Patti Smith Read from Virginia Woolf, and Hear the Only Surviving Recording of Woolf’s Voice Patti Smith’s New Haunting Tribute to Nico: Hear Three Tracks Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Hear Patti Smith Read the Poetry that Would Become Horses: A Reading of 14 Poems at Columbia University, 1975 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

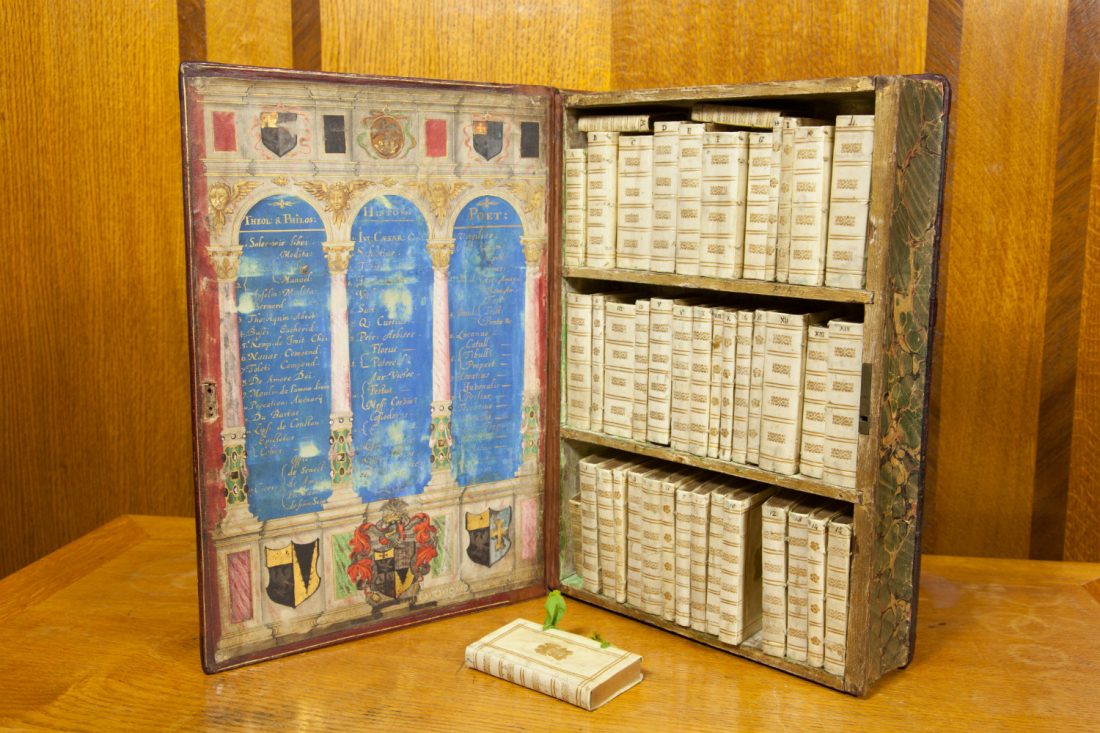

| 5:12p | Discover the Jacobean Traveling Library: The 17th Century Precursor to the Kindle

Image courtesy of the University at Leeds In the striking image above, you can see an early experiment in making books portable--a 17th century precursor, if you will, to the modern day Kindle. According to the library at the University of Leeds, this "Jacobean Travelling Library" dates back to 1617. That's when William Hakewill, an English lawyer and MP, commissioned the miniature library--a big book, which itself holds 50 smaller books, all "bound in limp vellum covers with coloured fabric ties." What books were in this portable library, meant to accompany noblemen on their journeys? Naturally the classics. Theology, philosophy, classical history, classical poetry. The works of Ovid, Seneca, Cicero, Virgil, Tacitus, and Saint Augustine. Many of the same texts that showed up in The Harvard Classics (now available online) three centuries later, and now our collection of Free eBooks. Apparently three other Jacobean Travelling Libraries were made. They now reside at the British Library, the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, and the Toledo Museum of Art in Toledo, Ohio. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: The Harvard Classics: Download All 51 Volumes as Free eBooks The Art of Making Old-Fashioned, Hand-Printed Books Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books Wearable Books: In Medieval Times, They Took Old Manuscripts & Turned Them into Clothes Free Online Literature Courses Discover the Jacobean Traveling Library: The 17th Century Precursor to the Kindle is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/08/02 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |