[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, August 17th, 2017

| Time | Event |

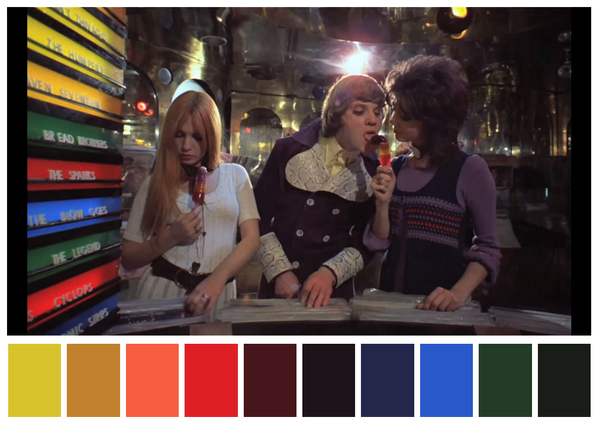

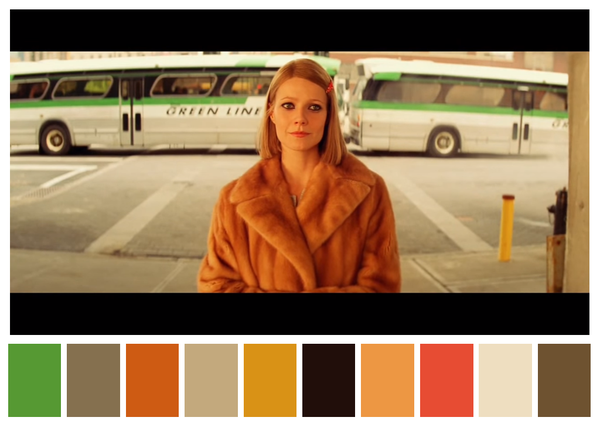

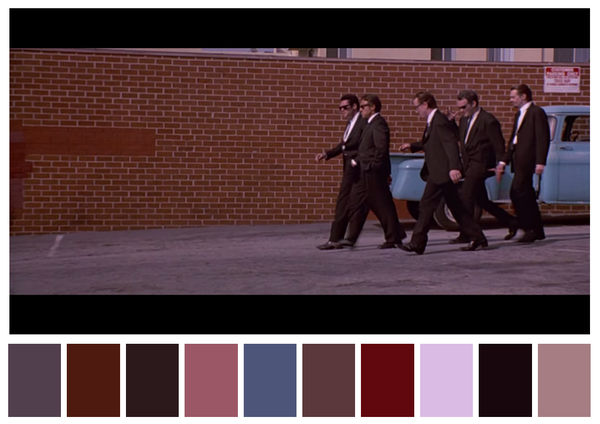

| 7:53a | The Color Palettes of Your Favorite Films: The Royal Tenenbaums, Reservoir Dogs, A Clockwork Orange, Blade Runner & More

We tend to think of film as roughly divided into the "black and white" and "color" eras, the latter ushered in by such lavish Technicolor productions as Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz. But we also know it's not as simple as that: those pictures came out in Hollywood's "golden year" of 1939, but some filmmakers had already been experimenting with color, and the golden age of black-and-white film would continue through the 1960s. Movies today still occasionally dare to venture into the never-entirely-shuttered realm of the monochrome, but on the whole, color reigns supreme.

Even though most movies now use color, few use it to its fullest advantage. Color gives viewers something more to look at, of course, but it can also give a movie its visual identity. Think of the films you've seen that you can call back most vividly to mind, almost as if you had a projector inside your head, and most of them will probably have a distinctive color palette. The most memorable cinematic images, in other words, will have been composed not just with any color they happened to need, but with a very specific set of colors, deliberately assembled by the filmmakers for its particular expressiveness.

For a few years now, the Twitter account Cinema Palettes has drawn out and isolated those colors, ten per film, for all to see. "Though based on a momentary still, each spectrum of shades seems to encapsulate its movie's overall mood," writes My Modern Met's Leah Pellegrini, pointing to "the somber, otherworldly blues of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, the dreamlike pinks and purples of The Grand Budapest Hotel, the cloyingly pretty pastels of Edward Scissorhands, and the earthly, organic greens and browns of Atonement."

It will surprise nobody to see the work of Wes Anderson, famed for the care he gives not just to color but every visual element of his film, appear more than once on the feed. Here we see Cinema Palettes' selections from The Royal Tenenbaums, as well as from Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs, Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, and Ridley Scott's Blade Runner. The project reveals an aspect of filmmaking that few of us may think consciously about, but nevertheless reflects the nature of cinema itself: the best films select not just the right colors but the right aspects of reality itself to present, to intensify, to diminish, and to leave out entirely. Explore more films and colors at Cinema Palettes. via My Modern Met and h/t Natalie W-S Related Content: “Bleu, Blanc, Rouge”: a Striking Supercut of the Vivid Colors in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960s Films Wes Anderson Likes the Color Red (and Yellow) Stanley Kubrick’s Obsession with the Color Red: A Supercut Early Experiments in Color Film (1895-1935) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Color Palettes of Your Favorite Films: The Royal Tenenbaums, Reservoir Dogs, A Clockwork Orange, Blade Runner & More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Legendary Animator Chuck Jones Creates an Oscar-Winning Animation About the Virtues of Universal Health Care (1949) While our country looks like it might be coming apart at the seams, it’s good to revisit, every once in a while, moments when it did work. And that’s not so that we can feel nostalgic about a lost time, but so that we can remind ourselves how, given the right conditions, things could work well once again. One example from history (and recently rediscovered by a number of blogs during the AHCA debacle in Congress) is this government propaganda film from 1949—the Harry S. Truman era—that promotes the idea of cradle-to-grave health care, and all for three cents a week. This money went to school nurses, nutritionists, family doctors, and neighborhood health departments. Directed by Chuck Jones, better known for animating Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, Daffy Duck, and the Road Runner, "So Much for So Little" follows our main character from infancy—where doctors help immunize babies against whooping cough, diphtheria, rheumatic fever, and smallpox—through school to dating, marriage, becoming parents, and settling into a nice, healthy retirement. Along the way, the government has made sure that health care is nothing to worry about. The film won an Academy Award in 1950 for Documentary Short Subject—not best sci-fi, despite how radical this all sounds. So what happened? John Maher at the blog Dot and Line puts it this way:

Three cents per American per week wouldn’t cut it now in terms of universal health coverage. But according to Maher, quoting a 2009 Kingsepp study on the original Affordable Care Act, taxpayers would have to pay $3.61 a week. So folks, don’t get despondent, get idealistic. The Greatest Generation came back from WWII with a grand idealism. Maybe this current generation just needs to fight and defeat Nazis all over again… Related Content: How to Draw Bugs Bunny: A Primer by Legendary Animator Chuck Jones This American Life Demystifies the American Healthcare System Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here. Legendary Animator Chuck Jones Creates an Oscar-Winning Animation About the Virtues of Universal Health Care (1949) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:00p | The Last Surviving Witness of the Lincoln Assassination Appears on the TV Game Show “I’ve Got a Secret” (1956) Let's rewind the videotape to 1956, to Samuel James Seymour's appearance on the CBS television show, "I've Got a Secret." At 96 years of age, Seymour was the last surviving person present at Ford's Theater the night Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth (April 14, 1865). Only five years old at the time, Mr. Seymour traveled with his father to Washington D.C. on a business trip, where they attended a performance of Our American Cousin. The youngster caught a quick glimpse of the president, the play began, and the rest is, well, history. A quick footnote: Samuel Seymour died two months after his TV appearance. His longevity had something to do, I imagine, with declining those Winstons over the years. Find courses on the Civil War in our list of Free History Courses, a subset of our collection, 1,250 Free Online Courses from Top Universities. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Note: This post originally appeared on our site in August, 2011. Related Content: Errol Morris Meditates on the Meaning and History of Abraham Lincoln’s Last Photograph Visualizing Slavery: The Map Abraham Lincoln Spent Hours Studying During the Civil War The Last Surviving Witness of the Lincoln Assassination Appears on the TV Game Show “I’ve Got a Secret” (1956) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:01p | Noam Chomsky Explains the Best Way for Ordinary People to Make Change in the World, Even When It Seems Daunting The threat of widespread violence and unrest descends upon the country, thanks again to a collection of actors viciously opposed to civil rights, and in many cases, to the very existence of people who are different from them. They have been given aid and comfort by very powerful enablers. Veteran activists swing into action. Young people on college campuses turn out by the hundreds week after week. But for many ordinary people with jobs, kids, mortgages, etc. the cost of participating in constant protests and civil actions may seem too great to bear. Yet, given many awful examples in recent history, the cost of inaction may be also. What can be done? Not all of us are Rosa Parks or Howard Zinn or Martin Luther King, Jr. or Thich Nat Hanh or Cesar Chavez or Dolores Huerta, after all. Few of us are revolutionaries and few may wish to be. Not everyone is brave enough or talented enough or knowledgeable enough or committed enough or, whatever. The problem with this kind of thinking is a problem with so much thinking about politics. We look to leaders—men and women we think of as superior beings—to do everything for us. This can mean delegating all the work of democracy to sometimes very flawed individuals. It can also mean we fundamentally misunderstand how democratic movements work. In the video above, Noam Chomsky addresses the question of what ordinary people can do in the face of seemingly insurmountable injustice. (The clip comes from the 1992 documentary Manufacturing Consent.) “The way things change,” he says, “is because lots of people are working all the time, and they’re working in their communities or their workplace or wherever they happen to be, and they’re building up the basis for popular movements.”

King himself often said as much. For example, in the Preface of his Stride Toward Freedom he wrote—referring to the 50,000 mostly ordinary, anonymous people who made the Montgomery Bus Boycott happen—“While the nature of this account causes me to make frequent use of the pronoun 'I,' in every important part of the story it should be ‘we.' This is not a drama with only one actor.” As for public intellectuals like himself engaged in political struggle, Chomsky says, “people like me can appear, and we can appear to be prominent… only because somebody else is doing the work.” He defines his own work as “helping people develop courses of intellectual self-defense” against propaganda and misinformation. For King, the issue came down to love in action. Responding in a 1963 interview above to a critical question about his methods, he counters the suggestion that nonviolence means sitting on the sidelines.

Both Chomsky, King, and every other voice for justice and human rights would agree that the people need to act instead of relying on movement leaders. Whatever actions one can take—whether it’s engaging in informed debate with family, friends, or coworkers, writing letters, making donations to activists and organizations, documenting injustice, or taking to the streets in protest or acts of civil disobedience—makes a difference. These are the small individual actions that, when practiced diligently and coordinated together in the thousands, make every powerful social movement possible. Related Content: Noam Chomsky Defines What It Means to Be a Truly Educated Person Read Martin Luther King and The Montgomery Story: The Influential 1957 Civil Rights Comic Book ‘Tired of Giving In’: The Arrest Report, Mug Shot and Fingerprints of Rosa Parks (December 1, 1955) Henry David Thoreau on When Civil Disobedience and Resistance Are Justified (1849) Saul Alinsky’s 13 Tried-and-True Rules for Creating Meaningful Social Change Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Noam Chomsky Explains the Best Way for Ordinary People to Make Change in the World, Even When It Seems Daunting is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/08/17 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |