[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, August 30th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 2:00p | Alice in Wonderland Gets Re-Envisioned by a Neural Network in the Style of Paintings By Picasso, van Gogh, Kahlo, O’Keeffe & More

An artist just starting out might first imitate the styles of others, and if all goes well, the process of learning those styles will lead them to a style of their own. But how does one learn something like an artistic style in a way that isn't simply imitative? Artificial intelligence, and especially the current developments in making computers not just think but learn, will certainly shed some light in the process — and produce, along the way, such fascinating projects as the video above, a re-envisioning of Disney's Alice in Wonderland in the styles of famous artists: Pablo Picasso, Georgia O'Keeffe, Katsushika Hokusai, Frida Kahlo, Vincent van Gogh and others. The idea behind this technological process, known as "style transfer," is "to take two images, say, a photo of a person and a painting, and use these to create a third image that combines the content of the former with the style of the later," says an explanatory post at the Paperspace Blog. "The central problem of style transfer revolves around our ability to come up with a clear way of computing the 'content' of an image as distinct from computing the 'style' of an image. Before deep learning arrived at the scene, researchers had been handcrafting methods to extract the content and texture of images, merge them and see if the results were interesting or garbage." Deep learning, the family of methods that enable computers to teach themselves, involves providing an artificial intelligence system called a "neural network" with huge amounts of data and letting it draw inferences. In experiments like these, the systems take in visual data and make inferences about how one set of data, like the content of frames of Alice in Wonderland, might look when rendered in the colors and contours of another, such as some of the most famous paintings in all of art history. (Others have tried it, as we've previously featured, with 2001: A Space Odyssey and Blade Runner.) If the technology at work here piques your curiosity, have a look at Google's free online course on deep learning or this new set of courses from Coursera— it probably won't improve your art skills, but it will certainly increase your understanding of a development that will play an ever larger role in the culture and economy ahead. Here's a full list of painters used in the neural networked version of Alice: Pablo Picasso via Kottke Related Content: What Happens When Blade Runner & A Scanner Darkly Get Remade with an Artificial Neural Network The First Film Adaptation of Alice in Wonderland (1903) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Alice in Wonderland Gets Re-Envisioned by a Neural Network in the Style of Paintings By Picasso, van Gogh, Kahlo, O’Keeffe & More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:31p | How to Listen to Music: A Free Course from Yale University Taught by Yale professor Craig Wright, this course, Listening to Music, operates on the assumption that listening to music is "not simply a passive activity one can use to relax, but rather, an active and rewarding process." When we understand the basic elements of Western music (e.g., rhythm, melody, and form), we can appreciate music in entirely new ways. That includes everything from classical music, rock and techno, to Gregorian chant and the blues. You can watch the 23 lectures above, on YouTube, or Yale's website, where you'll also find a syllabus and information on each class session. The main text used in the course is Listening to Music, written by the professor himself. Listening to Music will be added to the Music section of our ever-growing collection, 1,250 Free Online Courses from Top Universities. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: Playing an Instrument Is a Great Workout For Your Brain: New Animation Explains Why How to Listen to Music: A Free Course from Yale University is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

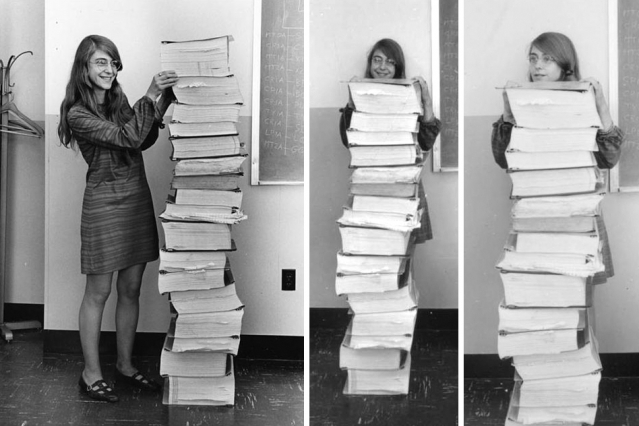

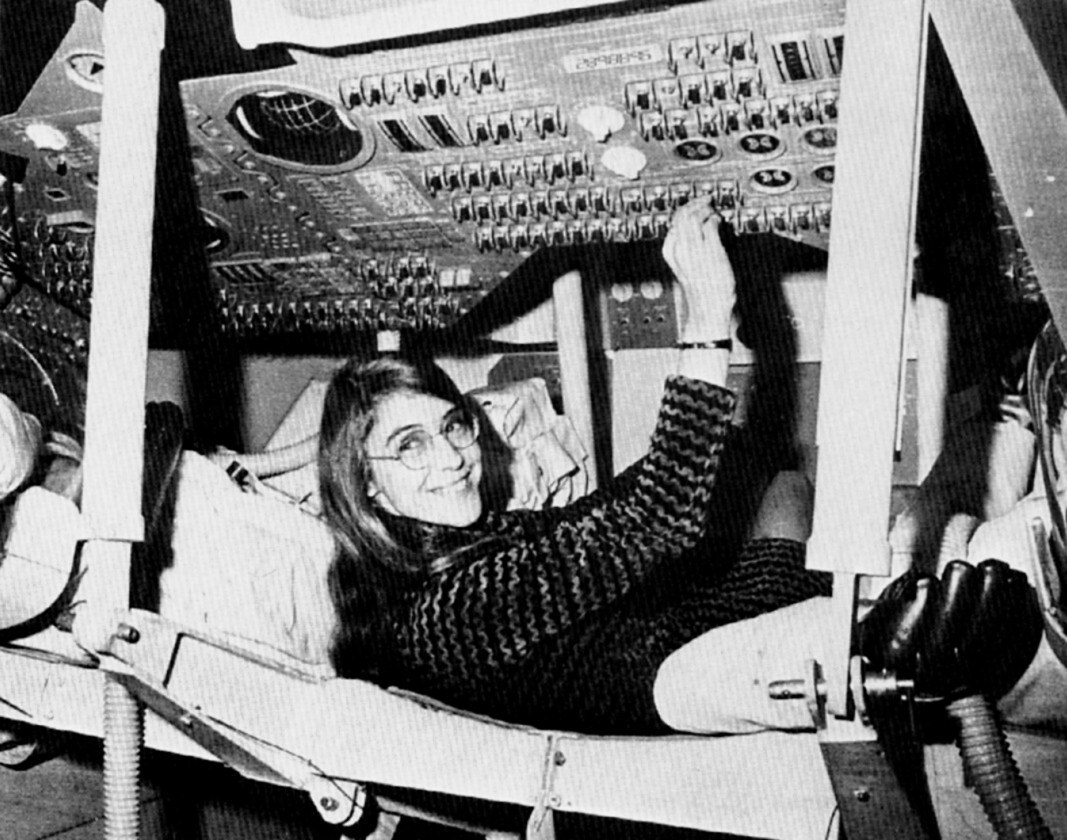

| 7:00p | Margaret Hamilton, Lead Software Engineer of the Apollo Project, Stands Next to Her Code That Took Us to the Moon (1969)

Photo courtesy of MIT Museum When I first read news of the now-infamous Google memo writer who claimed with a straight face that women are biologically unsuited to work in science and tech, I nearly choked on my cereal. A dozen examples instantly crowded to mind of women who have pioneered the very basis of our current technology while operating at an extreme disadvantage in a culture that explicitly believed they shouldn’t be there, this shouldn’t be happening, women shouldn’t be able to do a “man’s job!” The memo, as Megan Molteni and Adam Rogers write at Wired, “is a species of discourse peculiar to politically polarized times: cherry-picking scientific evidence to support a pre-existing point of view.” Its specious evolutionary psychology pretends to objectivity even as it ignores reality. As Mulder would say, the truth is out there, if you care to look, and you don’t need to dig through classified FBI files. Just, well, Google it. No, not the pseudoscience, but the careers of women in STEM without whom we might not have such a thing as Google. Women like Margaret Hamilton, who, beginning in 1961, helped NASA “develop the Apollo program’s guidance system” that took U.S. astronauts to the moon, as Maia Weinstock reports at MIT News. “For her work during this period, Hamilton has been credited with popularizing the concept of software engineering." Robert McMillan put it best in a 2015 profile of Hamilton:

Hamilton was indeed a mother in her twenties with a degree in mathematics, working as a programmer at MIT and supporting her husband through Harvard Law, after which she planned to go to graduate school. “But the Apollo space program came along” and contracted with NASA to fulfill John F. Kennedy’s famous promise made that same year to land on the moon before the decade’s end—and before the Soviets did. NASA accomplished that goal thanks to Hamilton and her team.

Photo courtesy of MIT Museum Like many women crucial to the U.S. space program (many doubly marginalized by race and gender), Hamilton might have been lost to public consciousness were it not for a popular rediscovery. “In recent years,” notes Weinstock, "a striking photo of Hamilton and her team’s Apollo code has made the rounds on social media.” You can see that photo at the top of the post, taken in 1969 by a photographer for the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory. Used to promote the lab’s work on Apollo, the original caption read, in part, “Here, Margaret is shown standing beside listings of the software developed by her and the team she was in charge of, the LM [lunar module] and CM [command module] on-board flight software team.” As Hank Green tells it in his condensed history above, Hamilton “rose through the ranks to become head of the Apollo Software development team.” Her focus on errors—how to prevent them and course correct when they arise—“saved Apollo 11 from having to abort the mission” of landing Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon’s surface. McMillan explains that “as Hamilton and her colleagues were programming the Apollo spacecraft, they were also hatching what would become a $400 billion industry.” At Futurism, you can read a fascinating interview with Hamilton, in which she describes how she first learned to code, what her work for NASA was like, and what exactly was in those books stacked as high as she was tall. As a woman, she may have been an outlier in her field, but that fact is much better explained by the Occam’s razor of prejudice than by anything having to do with evolutionary determinism. Note: You can now find Hamilton's code on Github. Related Content: How 1940s Film Star Hedy Lamarr Helped Invent the Technology Behind Wi-Fi & Bluetooth During WWII NASA Puts Its Software Online & Makes It Free to Download Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Margaret Hamilton, Lead Software Engineer of the Apollo Project, Stands Next to Her Code That Took Us to the Moon (1969) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:12p | An Animated Introduction to Ludwig Wittgenstein & His Philosophical Insights on the Problems of Human Communication In the recorded history of philosophy, there may be no sharper a mind than Ludwig Wittgenstein. A bête noire, enfant terrible, and all other such phrases used to describe affronts to order and decorum, Wittgenstein also represented an anarchic force that disturbed the staid discipline. His teacher Bertrand Russell recognized the existential threat Wittgenstein posed to his profession (though not right away). When Wittgenstein handed Russell the compact, cryptic Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, he admitted his student had gone beyond his own analytic insights in the pursuit of absolute clarity. Wittgenstein’s longtime mentor and friend, famed logician and mathematician Gottlob Frege, expressed criticism. Some have suggested he did so in part because he saw that Wittgenstein had rendered much of his work irrelevant. Alain de Botton gives a brief but fascinating sketch of Wittgenstein's ideas and incredibly odd biography in the School of Life video above. The eccentric Austrian savant, he asserts, “can help us with our communication problems” through his penetrating, though often impenetrable, claims about language. That may be so. But we may need to redefine what we mean by “communication.” According to Wittgenstein in the Tractatus, an overwhelming percentage of what we obsess about on a daily basis—political and religious abstractions, for example—is so totally incoherent and muddled that it means nothing at all. He revised this opinion dramatically in his later thought. Though he published nothing after the Tractatus and soon became a near-recluse after his startling entry into analytic philosophy, notes from his students were collected and published as well as a posthumous book called Philosophical Investigations. This version of Wittgenstein’s approach to the problems of communication involves a development of the “ostensive”—or demonstrative—role of language. Wittgenstein made an argument that language can only serve a social, rather than a personal, subjective, function. To make the point, he introduced his “Beetle in a Box” analogy, which you can see explained above in an animated BBC video written by Nigel Warburton and narrated by Aidan Turner. The analogy uses the idea of each of us claiming to have a beetle in a box as a stand in for our individual, private experiences. We all claim to have them (we can even observe brain states), but no one can ever see inside the theater of our minds to verify. We simply have to take each other's word for it. We play “language games,” which only have meaning in respect to their context. That such games can be mutually intelligible among individuals who are otherwise opaque to each other has to do with our shared environment, abilities, and limitations. Should we, however, meet a lion who could speak—in perfectly intelligible English—we would not, Wittgenstein asserted, be able to understand a single word. The vastly different experiences of human versus lion would not translate through any medium. Just above, we have an explanation of this thought experiment from an unlikely source, Ricky Gervais, in an attempted explanation to his comic foil Karl Pilkington, who takes things in his own peculiar direction. Though Wittgenstein used the idea for a different purpose, his observation about the unbridgeable chasm between humans and lions anticipates Thomas Nagel’s provocative claims in the 1974 essay “What is it like to be a bat?” We cannot inhabit the subjective states of beings so different from us, and therefore cannot say much of anything about their consciousness. Maybe it isn’t like anything to be a bat. Luckily for humans, we do have the ability to imagine each other’s experiences, in indirect, imperfect, roundabout, ways, and we all have enough shared context that we can, at least theoretically, use language to produce more clarity of thought and greater social harmony. Related Content: Hear Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus Sung as a One-Woman Opera In Search of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Secluded Hut in Norway: A Short Travel Film Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Short, Strange & Brutal Stint as an Elementary School Teacher Wittgenstein and Hitler Attended the Same School in Austria, at the Same Time (1904) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness An Animated Introduction to Ludwig Wittgenstein & His Philosophical Insights on the Problems of Human Communication is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/08/30 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |