[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Saturday, September 16th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 12:09a | Harry Dean Stanton (RIP) Reads Poems by Charles Bukowski Variety is reporting tonight that Harry Dean Stanton has died in Los Angeles, at the age of 91. He's best remembered, of course, for his roles in David Lynch's Twin Peaks, HBO's Big Love, Alex Cox's Repo Man, and Wim Wender's Paris, Texas. Over a 60 year career, Stanton made appearances in 116 films, 77 TV shows, and several music videos. He also lent his voice to an Alien video game and recorded poems by Charles Bukowski. Above and below, hear him read "Bluebird" and "Torched Out." Both recordings come from the 2003 documentary, Bukowski: Born Into This. Back in 2012, Stanton headlined an L.A. tribute to the Los Angeles poet. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: 900 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free Tom Waits Reads Two Charles Bukowski Poems, “The Laughing Heart” and “Nirvana” Watch “Beer,” a Mind-Warping Animation of Charles Bukowski’s 1971 Poem Honoring His Favorite Drink Harry Dean Stanton (RIP) Reads Poems by Charles Bukowski is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:00a | Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

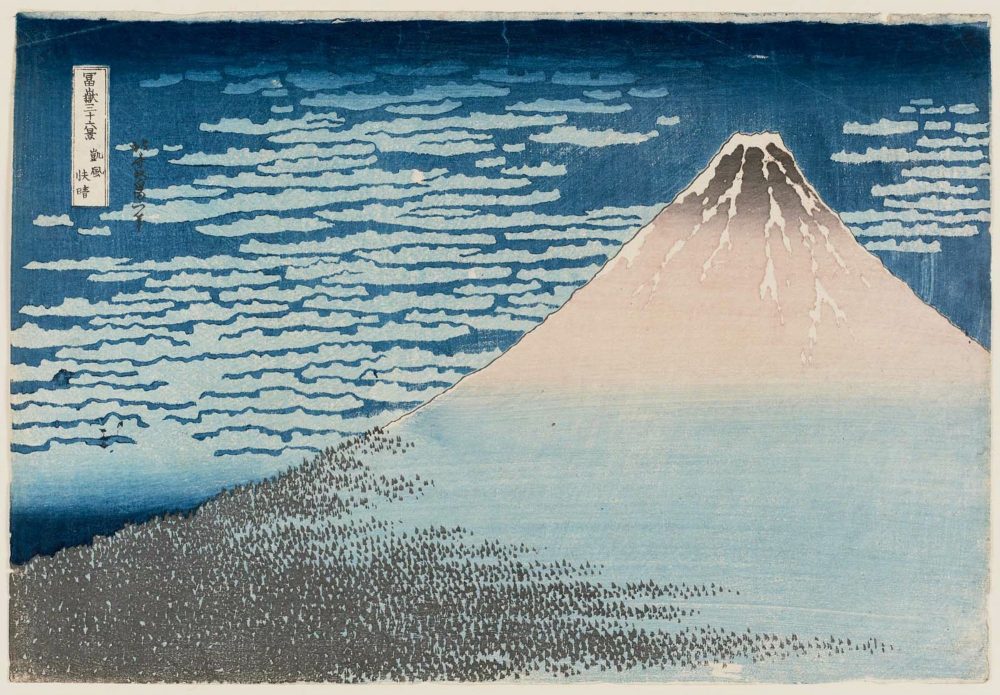

Most of us have now and again seen and appreciated Japanese woodblock prints, especially those in the tradition of ukiyo-e, those "captivating images of seductive courtesans, exciting kabuki actors, and famous romantic vistas." Those words come from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose essay on the art form describes how, "in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, woodblock prints depicting courtesans and actors were much sought after by tourists to Edo and came to be known as 'Edo pictures.' In 1765, new technology made possible the production of single-sheet prints in a range of colors," which brought about "the golden age of printmaking."

At that time, "the popularity of women and actors as subjects began to decline. During the early nineteenth century, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) brought the art of ukiyo-e full circle, back to landscape views, often with a seasonal theme, that are among the masterpieces of world printmaking." Even if you've only seen a few Japanese woodblock prints, you've seen the work of Hiroshige and Hokusai, thousands of examples of which you can find in the vast Japanese woodblock database of Ukiyo-e.org.

This English-Japanese bilingual site, a project of programmer and Khan Academy engineer John Resig, launched in 2012 and now boasts 213,000 prints from 24 museums, universities, libraries, auction houses, and dealers worldwide. You can search it by text or image (if you happen to have one of a print you'd like to identify), or you can browse by period and artist: not just the "golden age" of Hiroshige and Hokusai (1804 to 1868), but ukiyo-e's early years (early-mid 1700s), the birth of full-color printing (1740s to 1780s), the popularization of woodblock printing (1804 to 1868), the Meiji period (1868 to 1912), the artist-centric Shin Hanga and Sosaku Hanga movements (1915 to 1940s), and even the modern and contemporary era (1950s to now).

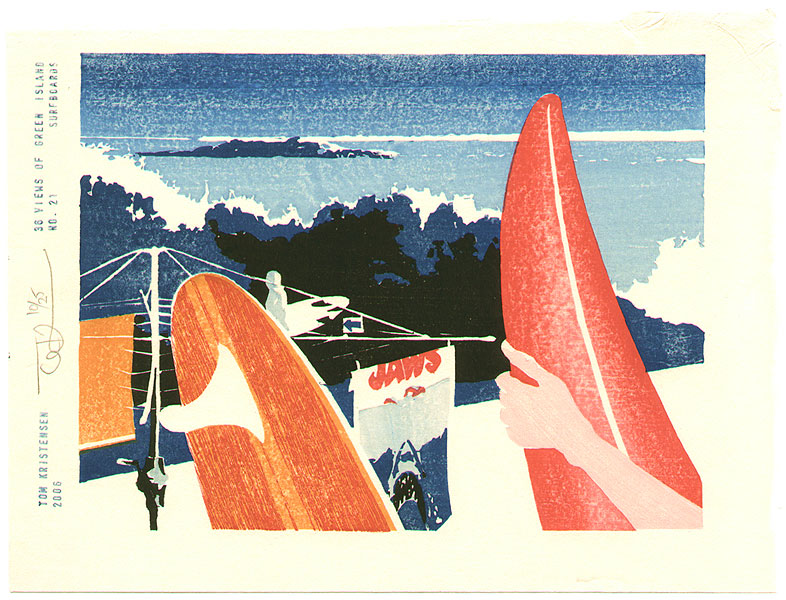

That last group includes woodblock prints of styles and subject matter one certainly wouldn't expect from classic ukiyo-e, though the works never go completely without connection to the tradition of previous masters. Some of these more recent practitioners, like Danish-German-Australian printmaker Tom Kristensen, have even gone so far as to not be Japanese. Kristensen, who "works in typically Japanese 'sosaku hanga' style: self-carved and self-printed with natural Japanese pigments on hand-made washi paper," has produced works like the 36 Views of Green Island series, of which number 21 appears below. The surfboards may at first seem incongruous, but one imagines that Hiroshige and Hokusai, those two great appreciators of waves, might approve. Enter the digital archive here, and note that if you click on an image, and then click on it again, you can view it in a larger format.

Related Content: Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600-1915) Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition Splendid Hand-Scroll Illustrations of The Tale of Genjii, The First Novel Ever Written (Circa 1120) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:30a | When Michel Foucault Tripped on Acid in Death Valley and Called It “The Greatest Experience of My Life” (1975)

Image by Nemomain, via Wikimedia Commons French theorist Michel Foucault rose to international prominence with his critical histories—or “archaeologies”—of scientific knowledge and technocratic power. His first book, Madness and Civilization, described the Enlightenment-era creation of insanity as a category set apart from reason, which enabled those labeled mad to be subjected to painful, invasive treatments and lose their freedom and agency during a period he called “the Great Confinement.” A follow-up, The Birth of the Clinic, appeared in 1963, introducing the notion of the “medical gaze,” a cold, probing ideological instrument that dehumanizes patients and allows people to be made into objects of experimentation. Foucault tended to view the world through a particularly grim, claustrophobic, even paranoid lens, though one arguably warranted by the well-documented histories he unearthed and the contemporary technocratic police states they gave rise to. But Foucault also insisted that in all relations of power, “there is necessarily the possibility of resistance.” His own forms of resistance tended toward political activism, adventurous sexual exploits, Zen meditation, and drugs. He grew pot on his balcony in Paris, did cocaine, smoked opium, and “deanatomized the localization of pleasure,” as he put it, with LSD. The experimentation constituted what he called a “limit experience” that transgressed the boundaries of a socially-imposed identity. But in a strange irony, the first time Foucault dropped acid, he himself became the subject of an experiment conducted on him by one of his followers, Simeon Wade, an assistant professor of history at Claremont Graduate School. In 1975 Foucault gave a seminar at UC Berkeley, where he would later finish his career in the years before his death nine years later. While there, he accepted an invitation from Wade and his partner Michael Stoneman (with Foucault above) to take a road trip to Death Valley. “I was performing an experiment,” Wade remembered in a recent interview on Boom California. “I wanted to see [how] one of the greatest minds in history would be affected by an experience he had never had before.”

The desert acid trip, Wade says, changed Foucault permanently, for the better. “Everything after this experience in 1975,” he says, “is the new Foucault, neo-Foucault…. Foucault from 1975 to 1984 was a new being.” The evidence seems clear enough. Foucault wrote Wade and Stoneman a few months later to tell them “it was the greatest experience of his life, and that it profoundly changed his life and his work…. He wrote us that he had thrown volumes two and three of his History of Sexuality into the fire and that he had to start over again.” Foucault had succumbed to despair prior to his Death Valley trip, Wade says, contemplating in his 1966 The Order of Things “the death of humanity…. To the point of saying that the face of man has been effaced.” Afterward, he was “immediately” seized by a new energy and focus. The titles of those last two, rewritten, books “are emblematic of the impact this experience had on him: The Uses of Pleasure and The Care of the Self, with no mention of finitude.” Foucault biographer James Miller tells us in the documentary above (at 27:30) —Michel Foucault Beyond Good and Evil— that everyone he spoke to about Foucault had heard about Death Valley, since Foucault told anyone who would listen that it was “the most transformative experience in his life.” There were some people, notes interviewer Heather Dundas, who believed that Wade’s experiment was unethical, that he had been “reckless with Foucault’s welfare.” To this challenge Wade replies, “Foucault was well aware of what was involved, and we were with him the entire time.” Asked whether he thought of the repercussions to his own career, however, he replies, “in retrospect, I should have.” Two years later, he left Claremont and could not find another full-time academic position. After obtaining a nursing license, he made a career as a nurse at the Los Angeles County Psychiatric Hospital and Ventura County Hospital, exactly the sort of institutions Foucault had found so threatening in his earlier work. Wade also authored a 121-page account of the Death Valley trip, and in 1978 published Chez Foucault, a mimeographed fanzine introduction to the philosopher's work, including an unpublished interview with Foucault. For his part, Foucault threw himself vigorously into the final phase of his career, in which he developed his concept of biopower, an ethical theory of self-care and a critical take on classical philosophical and religious themes about the nature of truth and subjectivity. He spent the last 9 years of his life pursuing the new pathways of thought that opened to him during those extraordinary ten hours under the hot sun and cool stars of the Death Valley desert. You can read the complete interview with Wade at BoomCalifornia.com. Related Content: Michel Foucault: Free Lectures on Truth, Discourse & The Self (UC Berkeley, 1980-1983) Hear Michel Foucault’s Lecture “The Culture of the Self,” Presented in English at UC Berkeley (1983) Watch a “Lost Interview” With Michel Foucault: Missing for 30 Years But Now Recovered Read Chez Foucault, the 1978 Fanzine That Introduced Students to the Radical French Philosopher Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness When Michel Foucault Tripped on Acid in Death Valley and Called It “The Greatest Experience of My Life” (1975) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:30a | Marie Curie Invented Mobile X-Ray Units to Help Save Wounded Soldiers in World War I

These days the phrase “mobile x-ray unit” is likely to spark heated debate about privacy, public health, and freedom of information, especially in New York City, where the police force has been less than forthcoming about its use of military grade Z Backscatter surveillance vans. A hundred years ago, Mobile X-Ray Units were a brand new innovation, and a godsend for soldiers wounded on the front in WW1. Prior to the advent of this technology, field surgeons racing to save lives operated blindly, often causing even more injury as they groped for bullets and shrapnel whose precise locations remained a mystery. Marie Curie was just setting up shop at Paris’ Radium Institute, a world center for the study of radioactivity, when war broke out. Many of her researchers left to fight, while Curie personally delivered France’s sole sample of radium by train to the temporarily relocated seat of government in Bordeaux. “I am resolved to put all my strength at the service of my adopted country, since I cannot do anything for my unfortunate native country just now…,” Curie, a Pole by birth, wrote to her lover, physicist Paul Langevin on New Year’s Day, 1915. To that end, she envisioned a fleet of vehicles that could bring X-ray equipment much closer to the battlefield, shifting their coordinates as necessary. Rather than leaving the execution of this brilliant plan to others, Curie sprang into action. She studied anatomy and learned how to operate the equipment so she would be able to read X-ray films like a medical professional. She learned how to drive and fix cars. She used her connections to solicit donations of vehicles, portable electric generators, and the necessary equipment, kicking in generously herself. (When she got the French National Bank to accept her gold Nobel Prize medals on behalf of the war effort, she spent the bulk of her prize purse on war bonds.) She was hampered only by backwards-thinking bureaucrats whose feathers ruffled at the prospect of female technicians and drivers, no doubt forgetting that most of France’s able-bodied men were otherwise engaged. Curie, no stranger to sexism, refused to bend to their will, delivering equipment to the front line and X-raying wounded soldiers, assisted by her 17-year-old daughter, Irène, who like her mother, took care to keep her emotions in check while working with maimed and distressed patients. "In less than two years," writes Amanda Davis at The Institute, "the number of units had grown substantially, and the Curies had set up a training program at the Radium Institute to teach other women to operate the equipment." Eventually, they recruited about 150 women, training them to man the Little Curies, as the mobile radiography units came to be known. Related Content: An Animated Introduction to the Life & Work of Marie Curie, the First Female Nobel Laureate Marie Curie’s Research Papers Are Still Radioactive 100+ Years Later Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her interest in women's wartime contributions has manifested itself in comics on "Crazy Bet" Van Lew and the Maidenform factory's manufacture of WWII carrier pigeon vests. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Marie Curie Invented Mobile X-Ray Units to Help Save Wounded Soldiers in World War I is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/09/16 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |