[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, September 21st, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 2:00p | Musician Taryn Southern Is Composing Her New Album with Artificial Intelligence: Hear the First Track “Break Free” is a new song by Taryn and Amper. The former, Taryn Southern, is a musician and singer popular on Youtube. The latter, however, is not human at all. Instead, Amper is an artificially intelligent music composer, producer and performer, developed by a combination of “music and technology experts” and now put to the test, being the engine behind Taryn’s single and eventually a full album, tentatively called I AM AI. To understand what is Taryn and what is Amper in this project, the singer talks about it in this Verge interview:

The key sentence for cynics is the second to last one. Amper delivers the familiar, or rather, Taryn makes Amper work until she gets something familiar. AI is not at the stage yet where it might surprise us with a decision, except in the cases where it goes spectacularly wrong. Right now it’s very good at learning patterns, at imitating, at delivering a variation on a theme. (That’s why it’s really good at imitation Bach, for example.) We could imagine, however, a future where AI would be able to take a number of musical elements, styles, and genres and come out with a hybrid that we’ve never heard before. And would that be any better than having a human do so? By the way, you can try out Amper yourself here. Your mileage may vary. Related content: Hear What Music Sounds Like When It’s Created by Synthesizers Made with Artificial Intelligence Artificial Intelligence Program Tries to Write a Beatles Song: Listen to “Daddy’s Car” Two Artificial Intelligence Chatbots Talk to Each Other & Get Into a Deep Philosophical Conversation Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here. Musician Taryn Southern Is Composing Her New Album with Artificial Intelligence: Hear the First Track is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:38p | Circus Artist Roxana Küwen Will Captivate You with Her Foot Juggling Routine Roxana Küwen is a German-born circus artist who "likes to take her audience into her world and make them be astonished, confused or amazed by playing with categories and presence." Witness the video above, where Küwen does something quite simple. She puts her feet next to her hands and moves her 20 digits in unison. Familiar body parts are put into strange motion, leaving you feeling charmed. But also a bit disconcerted. Then Roxana starts her foot juggling routine. It's not the most high velocity, risk-filled juggling act. The balls move slowly and never get more than a few feet off of the ground. There's a strange simplicity to it, though captivating nonetheless. Related Content Watch Marcel Marceau Mime The Mask Maker, a Story Created for Him by Alejandro Jodorowsky (1959) How Marcel Marceau Started Miming to Save Children from the Holocaust Circus Artist Roxana Küwen Will Captivate You with Her Foot Juggling Routine is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:00p | Behold the Mysterious Voynich Manuscript: The 15th-Century Text That Linguists & Code-Breakers Can’t Understand

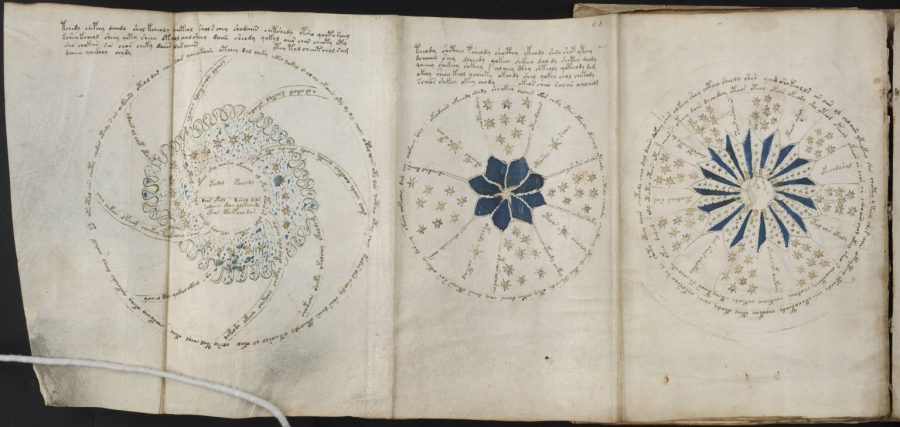

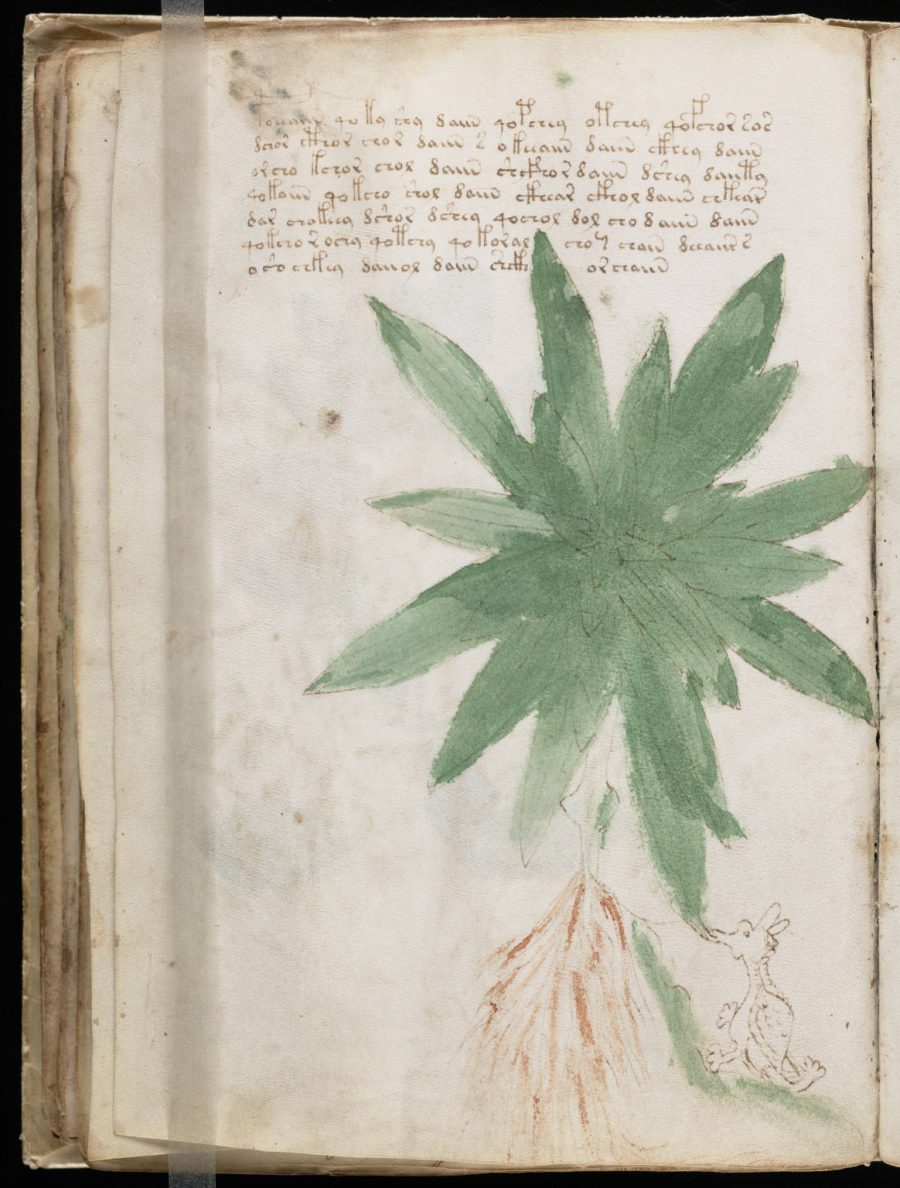

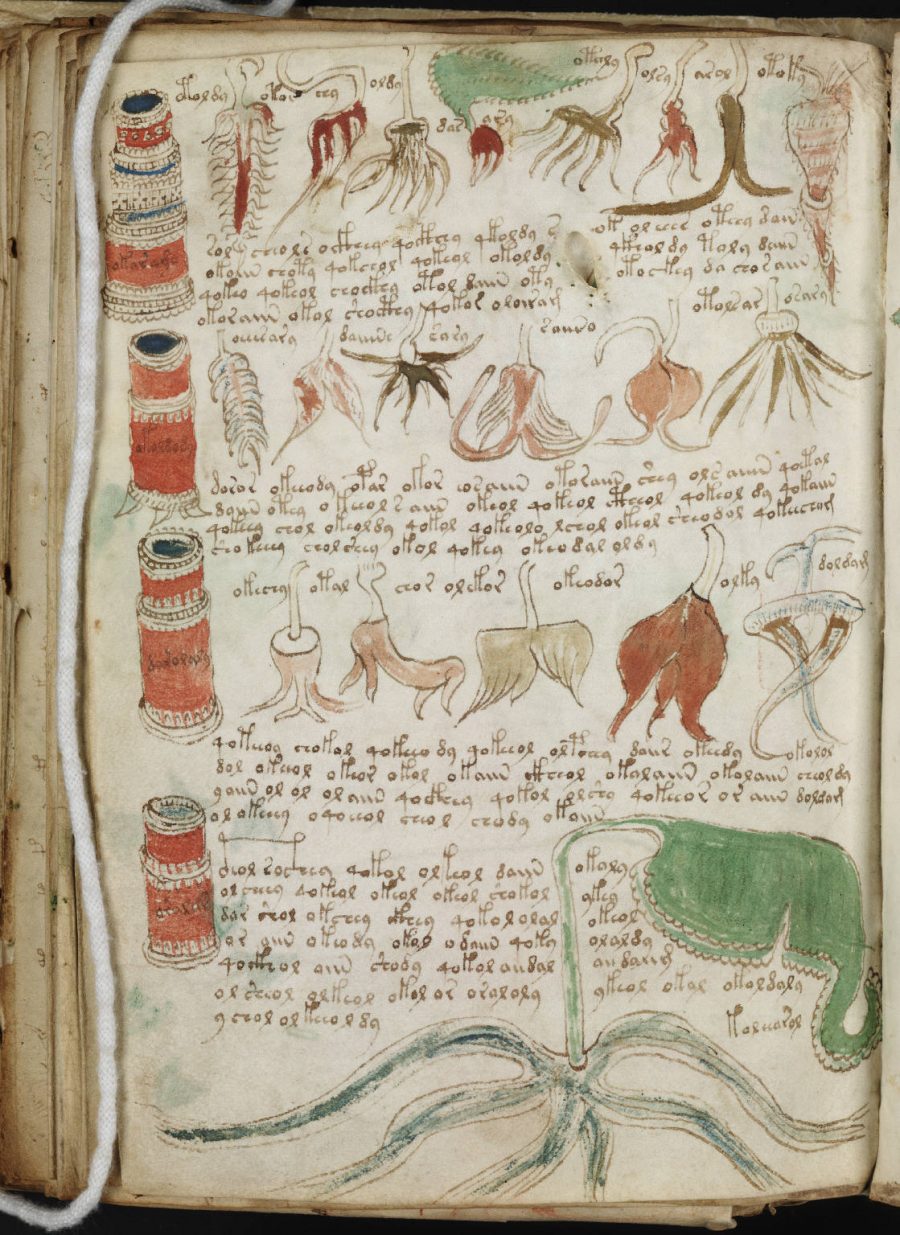

A 600-year-old manuscript—written in a script no one has ever decoded, filled with cryptic illustrations, its origins remaining to this day a mystery…. It’s not as satisfying a plot, say, of a National Treasure or Dan Brown thriller, certainly not as action-packed as pick-your-Indiana Jones…. The Voynich Manuscript, named for the antiquarian who rediscovered it in 1912, has a much more hermetic nature, somewhat like the work of Henry Darger; it presents us with an inscrutably alien world, pieced together from hybridized motifs drawn from its contemporary surroundings.

Voynich is unique for having made up its own alphabet while also seeming to be in conversation with other familiar works of the period, such that it resembles an uncanny doppelganger of many a Medieval text. A comparatively long book at 234 pages, it roughly divides into seven sections, any of which might be found on the shelves of your average 1400s European reader—a fairly small and rarified group. “Over time, Voynich enthusiasts have given each section a conventional name" for its dominant imagery: "botanical, astronomical, cosmological, zodiac, biological, pharmaceutical, and recipes.”

Scholars can only speculate about these categories. The manuscript's origins and intent have baffled cryptologists since at least the 17th century, when, notes Vox, “an alchemist described it as ‘a certain riddle of the Sphinx.’” We can presume, “judging by its illustrations,” writes Reed Johnson at The New Yorker, that Voynich is “a compendium of knowledge related to the natural world." But its “illustrations range from the fanciful (legions of heavy-headed flowers that bear no relation to any earthly variety) to the bizarre (naked and possibly pregnant women, frolicking in what look like amusement-park waterslides from the fifteenth century).”

The manuscript’s “botanical drawings are no less strange: the plants appear to be chimerical, combining incompatible parts from different species, even different kingdoms.” These drawings led scholar Nicholas Gibbs, the latest to try and decipher the text, to compare it to the Trotula, a Medieval compilation that “specializes in the diseases and complaints of women,” as he wrote in a Times Literary Supplement article earlier this month. It turns out, according to several Medieval manuscript experts who have studied the Voynich, that Gibbs’ proposed decoding may not actually solve the puzzle.

The degree of doubt should be enough to keep us in suspense, and therein lies the Voynich Manuscript’s enduring appeal—it is a black box, about which we might always ask, as Sarah Zhang does, “What could be so scandalous, so dangerous, or so important to be written in such an uncrackable cipher?” Wilfred Voynich himself asked the same question in 1912, believing the manuscript to be “a work of exceptional importance… the text must be unraveled and the history of the manuscript must be traced.” Though “not an especially glamorous physical object,” Zhang observes, it has nonetheless taken on the aura of a powerful occult charm.

But maybe it’s complete gibberish, a high-concept practical joke concocted by 15th century scribes to troll us in the future, knowing we’d fill in the space of not-knowing with the most fantastically strange speculations. This is a proposition Stephen Bax, another contender for a Voynich solution, finds hardly credible. “Why on earth would anyone waste their time creating a hoax of this kind?,” he asks. Maybe it's a relic from an insular community of magicians who left no other trace of themselves. Surely in the last 300 years every possible import has been suggested, discarded, then picked up again. Should you care to take a crack at sleuthing out the Voynich mystery—or just to browse through it for curiosity’s sake—you can find the manuscript scanned at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, which houses the vellum original. Or flip through the Internet Archive’s digital version above. Another privately-run site contains a history and description of the manuscript and annotations on the illustrations and the script, along with several possible transcriptions of its symbols proposed by scholars. Good luck! Related Content: 1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books Wearable Books: In Medieval Times, They Took Old Manuscripts & Turned Them into Clothes Carl Jung’s Hand-Drawn, Rarely-Seen Manuscript The Red Book: A Whispered Introduction Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Behold the Mysterious Voynich Manuscript: The 15th-Century Text That Linguists & Code-Breakers Can’t Understand is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00p | The Smithsonian Design Museum Digitizes 200,000 Objects, Giving You Access to 3,000 Years of Design Innovation & History

John Lennon poster by Richard Avedon When we think of design, each of us thinks of it in our own way, focusing on our own interests: illustration, fashion, architecture, interfaces, manufacturing, or any of a vast number of sub-disciplines besides. Those of us who have paid a visit to Cooper Hewitt, also known as the Smithsonian Design Museum, have a sense of just how much human innovation, and even human history, that term can encompass. Now, thanks to an ambitious digitization project that has so far put 200,000 items (or 92 percent of the museum's collection) online, you can experience that realization virtually.

Concept car designed by William McBride The video below explains the system, an impressive feat of design in and of itself, with which Cooper Hewitt made this possible. "In collaboration with the Smithsonian’s Digitization Program Office, the mass digitization project transformed a physical object (2-D or 3-D) from the shelf to a virtual object in one continuous process," says its about page. "At its peak, the project had four photographic set ups in simultaneous operation, allowing each to handle a certain size, range and type of object, from minute buttons to large posters and furniture. A key to the project’s success was having a completely barcoded collection, which dramatically increased efficiency and allowed all object information to be automatically linked to each image." Given that the items in Cooper Hewitt's collection come from all across a 3000-year slice of history, you'll need an exploration strategy or two. Have a look at the collection highlights page and you'll find curated sections housing the items pictured here, including psychedelic posters, designs for automobiles, architect's eye, and designs for the Olympics — and that's just some of the relatively recent stuff. Hit the random button instead and you may find yourself beholding, in high resolution, anything from a dragonish fragment of a panel ornament from 18th-century France to a late 19th-century collar to a Swedish vase from the 1980s.

Mexico 68 designed by Lance Wyman Cooper Hewitt has also begun integrating its online and offline experiences, having installed a version of its collection browser on tables in its physical galleries. There visitors can "select items from the 'object river' that flows down the center of each table" about which to learn more, as well as use a "new interactive Pen" that "further enhances the visitor experience with the ability to “collect” and “save” information, as well as create original designs on the tables." So no matter how much time you spend with Cooper Hewitt's online collection — and you could potentially spend a great deal — you might, should you find yourself on Manhattan's Museum Mile, consider stopping into the museum to see how physical and digital design can work together. Enter the Cooper Hewitt's online collection here.

Temple of Curiosity by Etienne-Louis Boullée Related Content: Free: A Crash Course in Design Thinking from Stanford’s Design School Bauhaus, Modernism & Other Design Movements Explained by New Animated Video Series Abstract: Netflix’s New Documentary Series About “the Art of Design” Premieres Today The Smithsonian Picks “101 Objects That Made America” Smithsonian Digitizes & Lets You Download 40,000 Works of Asian and American Art Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Smithsonian Design Museum Digitizes 200,000 Objects, Giving You Access to 3,000 Years of Design Innovation & History is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/09/21 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |