[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, October 3rd, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 4:36a | Watch Tom Petty (RIP) and the Heartbreakers Perform Their Last Song Together, “American Girl”: Recorded on 9/25/17 It was already a terrible day. Then came the news (retracted, then later sadly confirmed by The New York Times and the BBC) that Tom Petty has passed away at the age of 66. The cause, apparently a heart attack. This summer, I traveled to Philadelphia to see my first Tom Petty show, knowing it might be, as he said, his "last trip around the country," the final big tour. And I'm so glad I did. What more could I say? It was a wonderful show, a magical two-hour singalong, which ended with "American Girl," one of my favorites. Above, you can see Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers play their last song together--again "American Girl"--at their final gig at the Hollywood Bowl. This video was recorded just last week. If you've never given their music a serious listen, just click play on the playlist below. It might be one of the best wall-to-wall hours in music. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials.

Watch Tom Petty (RIP) and the Heartbreakers Perform Their Last Song Together, “American Girl”: Recorded on 9/25/17 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:30p | The Famously Controversial “Monty Hall Problem” Explained: A Classic Brain Teaser When the news broke last week of the death of game-show host Monty Hall, even those of us who couldn't quite put a face to the name felt the ring of recognition from the name itself. Hall became famous on the long-running game show Let's Make a Deal, whose best-known segment "Big Deal of the Day" had him commanding his players to choose one of three numbered doors, each of which concealed a prize of unknown desirability. It put not just phrases like "door number three" into the English lexicon but contributed to the world of stumpers the Monty Hall Problem, the brain-teaser based on the much-contested probability behind which door a contestant should choose. Let's Make a Deal premiered in 1963, but only in 1990, when Marilyn vos Savant wrote one of her Q&A columns about it in Parade magazine, did the Monty Hall Problem draw serious, frustrated public attention. "Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats," went the question, setting up a Let's Make a Deal-like scenario. "You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, 'Do you want to pick door No. 2?' Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?" Yes, replied the unhesitating Savant and her Guinness World Record-setting IQ, you should switch. "The first door has a 1/3 chance of winning, but the second door has a 2/3 chance." This logic, which you can see broken down by University of California, Berkeley statistics professor Lisa Goldberg in the Numberphile video at the top of the post, drew about 10,000 letters of disagreement in total, many from academics at respectable institutions. Michael Shermer received a similarly vehement response when he addressed the issue in Scientific American eighteen years later. "At the beginning of the game you have a 1/3rd chance of picking the car and a 2/3rds chance of picking a goat," he explained. "Switching doors is bad only if you initially chose the car, which happens only 1/3rd of the time. Switching doors is good if you initially chose a goat, which happens 2/3rds of the time." Thus the odds of winning by switching becomes two out of three, double those of not switching. Useful advice, presuming you'd prefer a Bricklin SV-1 or an Opel Manta to a goat, and that the host opens one of the unselected doors every time without fail, which Hall didn't actually do. When he did open it, he later explained, the contestants made the same assumption many of Savant and Shermer's complainants did: "They'd think the odds on their door had now gone up to 1 in 2, so they hated to give up the door no matter how much money I offered. By opening that door we were applying pressure." Ultimately, "if the host is required to open a door all the time and offer you a switch, then you should take the switch. But if he has the choice whether to allow a switch or not, beware. Caveat emptor. It all depends on his mood" — a rare consideration in anything related to mathematics, but when dealing with the Monty Hall problem, one ignores at one's peril the words of Monty Hall. Related Content: Are You One of the 2% Who Can Solve “Einstein’s Riddle”? Can You Solve These Animated Brain Teasers from TED-Ed? John Cage Performs Water Walk on US Game Show I’ve Got a Secret (1960) A Young Hunter S. Thompson Appears on the Classic TV Game Show, To Tell the Truth (1967) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Famously Controversial “Monty Hall Problem” Explained: A Classic Brain Teaser is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

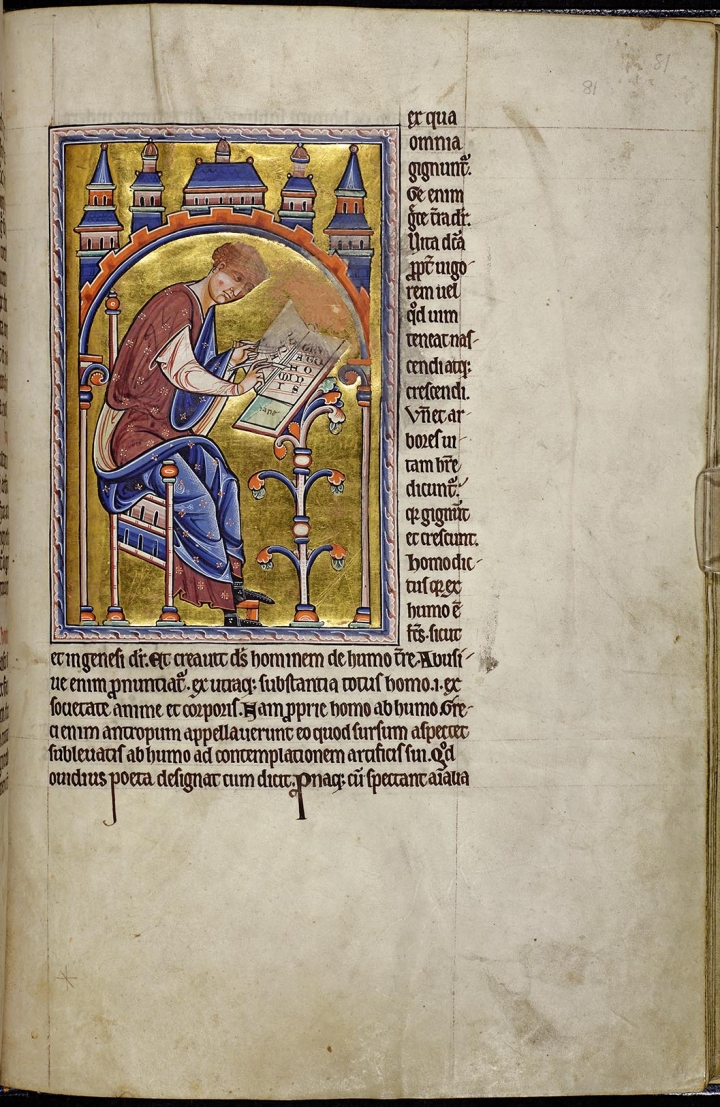

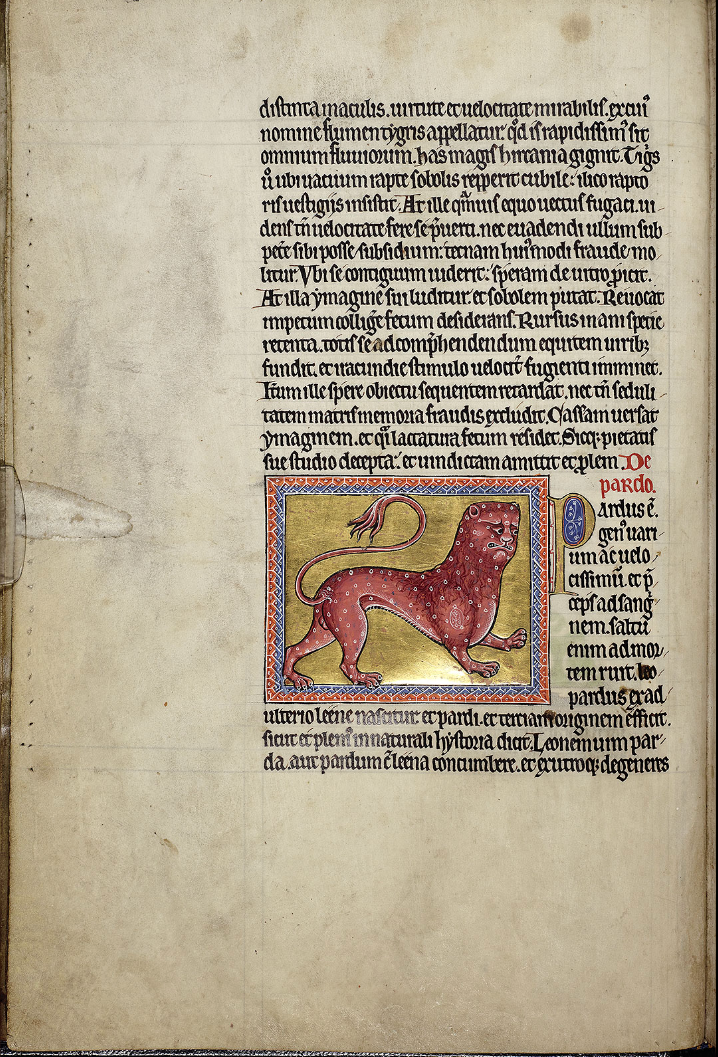

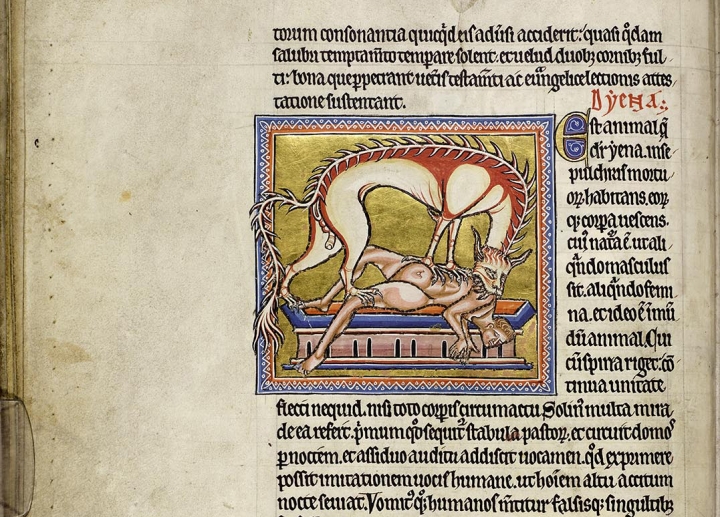

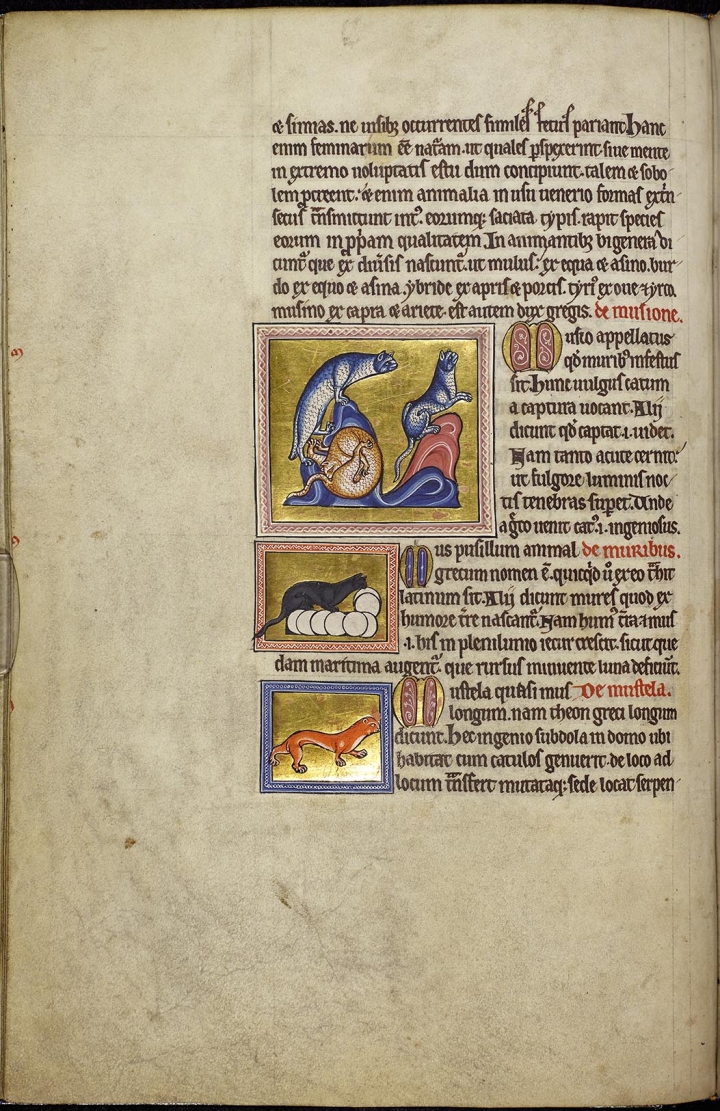

| 5:00p | The Aberdeen Bestiary, One of the Great Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts, Now Digitized in High Resolution & Made Available Online

For thousands of years, ordinary people all over the world not only worked side-by-side with domestic animals on a daily basis, they also observed the wild fauna around them to learn how to navigate and survive nature. The closeness produced a keen appreciation for animal behavior that informs the folk tales of every continent and the popular texts of every religion. Our delight in animal stories survives in children’s books, but in grown-up language, animal comparisons tend to be nasty and dehumanizing. The demeaning adjective “bestial” conveys a typical attitude not only toward people we don’t like, but toward the animal world as well. Orwell’s Animal Farm and Kafka’s Metamorphosis have become the standard references for modern animal allegory.

Early literature shows us a range of different attitudes, where animals are treated as equals, with character traits both good and bad, or as noble messengers of a god or gods rather than livestock, moving scenery, or exploitable resources. We might refer in an eastern context to the Jataka Tales, fables of the Buddha’s many rebirths in the human and animal worlds that provide their readers with moral lessons. In the Christian west, we have the medieval bestiary—compendiums of animals, both real and mythological—that introduced readers to a moral typology through “reading” what early Christians thought of as the “book of nature.”

The most lavish of them all, the Aberdeen Bestiary, which dates from around 1200, was once owned by Henry VIII. Now, the University of Aberdeen has digitized the text and made it freely available to readers online. Beginning with the key creation stories from the book of Genesis, the book then dives into its descriptions of animals, beginning with the lion, the pard (panther), and the elephant. You'll notice that these are not animals that your typical medieval European reader would have encountered. One important difference between the bestiary and the fable is that the former draws many of its beasts from hearsay, conjecture, or pure fiction. But the intent is partly the same. These “were teaching tools,” notes Claire Voon at Hyperallergic, and the Aberdeen Bestiary contains illustrated “lengthy tales of moral behavior.”

Like the stories of Aesop, the bestiary presents important lessons, mixing in the fabulous with the naturalist. As Voon describes the Aberdeen Bestiary:

Incredibly ornate and bearing the marks of dozens of scribal hands, the book, historians believe, was originally produced for a wide audience, then taken by Henry’s librarians from a dissolved monastery. Never fully completed, it remained in the Royal Library for 100 years after Henry. “I doubt if the Tudor monarchs took it out for a regular read,” says Aberdeen University professor Jane Geddes. Now an open public document, it returns to its“original purpose of education,” writes Voon, “although for us, of course, it illuminates more about the past than the present.” See the high res scans here.

via Hyperallergic Related Content: Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books Leonardo da Vinci’s Bizarre Caricatures & Monster Drawings 1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Aberdeen Bestiary, One of the Great Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts, Now Digitized in High Resolution & Made Available Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:00p | How Buddhism & Neuroscience Can Help You Change How Your Mind Works: A New Course by Bestselling Author Robert Wright Buddhist thought and culture has long found a comfortable home among hippies, beatniks, New Age believers, artists, occultists and mystics. Recently, many of its tenets and practices have become widely popular among very different demographics of scientists, skeptics, and atheist communities. It may seem odd that an increasingly secularizing West would widely embrace an ancient Eastern religion. But even the Dalai Lama has pointed out that Buddhism’s essential doctrines align uncannily with the findings of modern science The Pali Canon, the earliest collection of Buddhist texts, contains much that agrees with the scientific method. In the Kalama Sutta, for example, we find instructions for how to shape views and beliefs that accord with the methods espoused by the Royal Society many hundreds of years later. Robert Wright—bestselling author and visiting professor of religion and psychology at Princeton and Penn—goes even further, showing in his book Why Buddhism is True how Buddhist insights into impermanence, delusion, ignorance, and unhappiness align with contemporary findings of neuroscience and evolutionary biology. Wright is now making his argument for the compatibility of Buddhism and science in a new MOOC from Coursera called “Buddhism and Modern Psychology.” You can watch the trailer for the course, which starts this week, just above. The core of Buddhism is generally contained in the so-called “Four Noble Truths,” and Wright explains in his lecture above how these teachings sum up the problem we all face, beginning with the first truth of dukkha. Often translated as “suffering,” the word might better be thought of as meaning “unsatisfactoriness,” as Wright illustrates with a reference to the Rolling Stones. Jagger's “can't get no satisfaction,” he says, captures “a lot of the spirit of what is called the First Noble Truth,” which, along with the Second, constitutes “the Buddha’s diagnosis of the human predicament.” Not only can we not get what we want, but even when we do, it hardly ever makes us happy for very long. Rather than impute our misery to the displeasure of the gods, the Buddha, Wright tells Lion’s Roar, “says the reason we suffer, the reason we’re not enduringly satisfied, is that we don’t see the world clearly. That’s also the reason we sometimes fall short of moral goodness and treat other human beings badly.” Desperate to hold on to what we think will satisfy us, we become consumed by craving, as the Second Noble Truth explains, constantly clinging to pleasure and fleeing from pain. Just above, Wright explains how these two claims compare with the theories of evolutionary psychology. His course also explores how meditation releases us from craving and breaks the vicious cycle of desire and aversion. Overall, the issues Wright addresses are laid out in his course description:

As to the last question, Wright is not alone among scientifically-minded people in answering with a resounding yes. Rather than relying on the beneficence of a supernatural savior, Buddhism offers a course of treatment—the “Noble Eightfold Path”—to combat our disposition toward illusory thinking. We are shaped by evolution, Wright says, to deceive ourselves. The Buddhist practices of meditation and mindfulness, and the ethics of compassion and nonharming, are “in some sense, a rebellion against natural selection.” You can see more of Wright’s lectures on YouTube. Wright's free course, Buddhism and Modern Psychology, is getting started this week. You can sign up now. Related Content: Daily Meditation Boosts & Revitalizes the Brain and Reduces Stress, Harvard Study Finds Philosopher Sam Harris Leads You Through a 26-Minute Guided Meditation Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Buddhism & Neuroscience Can Help You Change How Your Mind Works: A New Course by Bestselling Author Robert Wright is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/10/03 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |