[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, October 12th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | John Coltrane Draws a Mysterious Diagram Illustrating the Mathematical & Mystical Qualities of Music

In a post earlier this year, we wrote about a drawing John Coltrane gave his friend and mentor Yusef Lateef, who reproduced it in his book Repository of Scales and Melodic Patterns. The strange diagram contains the easily recognizable circle of fifths (or circle of fourths), but it illustrates a much more sophisticated scheme than basic major scale theory. Just exactly what that is, however, remains a mystery. Like every mystical explorer, the work Coltrane left behind asks us to expand our consciousness beyond its narrow boundaries. The diagram may well show a series of “multiplicities,” as saxophonist Ed Jones writes. From the way Coltrane has “grouped certain pitches,” writes vibes player Corey Mwamba, “it’s easy to infer that Coltrane is displaying a form of chromatic modulation.” These observations, however, fail to explain why he would need such a chart. “The diagram,” writes Mwamba, “may have a theoretical basis beyond that.” But does anyone know what that is? Perhaps Coltrane cleared certain things up with his “corrected” version of the tone circle, above, which Lateef also reprinted. From this—as pianist Matt Ratcliffe found—one can derive Giant Steps, as well as “the Star of David or the Seal of Solomon, very powerful symbolism especially to ancient knowledge and the Afrocentric and eventually cosmic consciousness direction in which Coltrane would ultimately lead on to with A Love Supreme.” Sound too far out? On the other side of the epistemological spectrum, we have physicist and sax player Stephon Alexander, who writes in his book The Jazz of Physics that “the same geometric principle that motivated Einstein’s theory was reflected in Coltrane’s diagram.” Likewise, saxophonist Roel Hollander sees in the tone circle a number of mathematical principles. But, remaining true to Coltrane’s synthesis of spirituality and science, he also reads its geometry according to sacred symbolism. In a detailed exploration of the math in Coltrane’s music, Hollander writes, “all tonics of the chords used in ‘Giant Steps’ can be found back at the Circle of Fifths/Fourths within 2 of the 4 augmented triads within the octave.” Examining these interlocking shapes shows us a hexagram, or Star of David, with the third triad suggesting a three-dimensional figure, a “star tetrahedron,” adds Hollander, “also known as ‘Merkaba,” which means “light-spirit-body” and represents “the innermost law of the physical world.” Do we actually find such heavy mystical architecture in the Coltrane Circle?—a “’divine light vehicle’ allegedly used by ascended masters to connect with and reach those in tune with the higher realms, the spirit/body surrounded by counter-rotating fields of light (wheels within wheels)”? As the occult/magical/Kabbalist associations within the circle increase—the numerology, divine geometry, etc.—we can begin to feel like Tarot readers, joining a collection of random symbolic systems together to produce the results we like best. “That the diagram has to do with something,” writes Mwamba, “is not in doubt: what it has to do with a particular song is unclear.” After four posts in which he dissects both versions of the circle and ponders over the pieces, Mwanda still cannot definitively decide. “To ‘have an answer,’” he writes, “is to directly interpret the diagram from your own viewpoint: there’s a chance that what you think is what John Coltrane thought, but there’s every chance that it is not what he thought.” There’s also the possibility no one can think what Coltrane thought. The circle contains Coltrane’s musical experiments, yet cannot be explained by them; it hints at theoretical physics and the geometry of musical composition, while also making heavy allusion to mystical and religious symbolism. The musical relationships it constructs seem evident to those with a firm grasp of theory; yet its strange intricacies may be puzzled over forever. “Coltrane’s circle,” writes Faena Aleph, is a “mandala,” expressing “precisely what is, at once, both paradoxical and obvious.” Ultimately, Mwamba concludes in his series on the diagram, "it isn't possible to say that Coltrane used the diagram at all; but exploring it in relation to what he was saying at the time has led to more understanding and appreciation of his music and life." The circle, that is, works like a key with which we might unlock some of the mysteries of Coltrane's later compositions. But we may never fully grasp its true nature and purpose. Whatever they were, Coltrane never said. But he did believe, as he tells Frank Kofsky in the 1966 interview above, in music's ability to contain all things, spiritual, physical, and otherwise. "Music," he says, "being an expression of the human heart, or of the human being itself, does express just what is happening. The whole of human experience at that particular time is being expressed." Related Content: Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” Animated (Part II) A New Mural Pays Tribute to John Coltrane in Philadelphia Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness John Coltrane Draws a Mysterious Diagram Illustrating the Mathematical & Mystical Qualities of Music is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

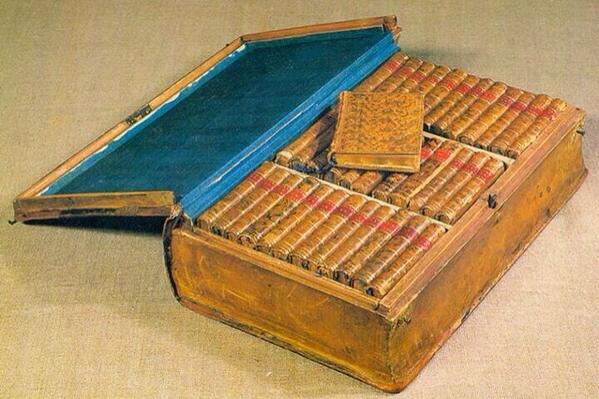

| 11:00a | Napoleon’s Kindle: See the Miniaturized Traveling Library He Took on Military Campaigns

Every piece of technology has a precedent. Most have several different types of precedents. You've probably used (and may well own) an eBook reader, for instance, but what would have afforded you a selection of reading material two or three centuries ago? If you were a Jacobean Englishman of means, you might have used the kind of traveling library we featured in August, a handsome portable case custom-made for your books. (If you're Tom Stoppard in the 21st century, you still do.) If you were Napoleon, who seemed to love books as much as he loved military power — he didn't just amass a vast collection of them, but kept a personal librarian to oversee it — you'd take it a big step further. "Many of Napoleon’s biographers have incidentally mentioned that he […] used to carry about a certain number of favorite books wherever he went, whether traveling or camping," says an 1885 Sacramento Daily Union article posted by Austin Kleon, "but it is not generally known that he made several plans for the construction of portable libraries which were to form part of his baggage." The piece's main source, a Louvre librarian who grew up as the son of one of Napoleon's librarians, recalls from his father's stories that "for a long time Napoleon used to carry about the books he required in several boxes holding about sixty volumes each," each box first made of mahogany and later of more solid leather-covered oak. "The inside was lined with green leather or velvet, and the books were bound in morocco," an even softer leather most often used for bookbinding. To use this early traveling library, Napoleon had his attendants consult "a catalogue for each case, with a corresponding number upon every volume, so that there was never a moment’s delay in picking out any book that was wanted." This worked well enough for a while, but eventually "Napoleon found that many books which he wanted to consult were not included in the collection," for obvious reasons of space. And so, on July 8, 1803, he sent his librarian these orders:

In sum: not only did Napoleon possess a traveling library, but when that traveling library proved too cumbersome for his many and varied literary demands, he had a whole new set of not just portable book cases but even more portable books made for him. (You can see how they looked packed away in the image tweeted by Cork County Library above.) This prefigured in a highly analog manner the digital-age concept of recreating books in another format specifically for compactness and convenience — the kind of compactness and convenience now increasingly available to all of us today, and to a degree Napoleon never could have imagined, let alone demanded. It's always good to be the Emperor, but in many ways, it's better to be a reader in the 21st century. Related Content: Discover the Jacobean Traveling Library: The 17th Century Precursor to the Kindle Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Stanley Kubrick Never Made Vintage Photos of Veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, Taken Circa 1858 Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Napoleon’s Kindle: See the Miniaturized Traveling Library He Took on Military Campaigns is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | If You Drive Down a Stretch of Route 66, the Road Will Play “America the Beautiful” If you find yourself in New Mexico, traveling down a stretch of Route 66, you can drive over a quarter mile-long rumble strip and your car's tires will play "America the Beautiful." That's assuming you're driving at the speed limit, 45 miles per hour. Don't believe me? Watch the clip above. As Atlas Obscura explains, the "Musical Highway" or "Singing Highway" was "installed in 2014 as part of a partnership between the New Mexico Department of Transportation and the National Geographic Channel." It's all part of an elaborate attempt to get drivers to slow down and obey the speed limit. "Getting the rumble strips to serenade travelers required a fair bit of engineering. The individual strips had to be placed at the precise distance from one another to produce the notes they needed to sing their now-signature song." You'll find this particular stretch of road between Albuquerque and Tijeras. Here's the location on Google Maps. Other musical rumble strips have popped up in Denmark, Japan and South Korea. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: Jack Kerouac’s On The Road Turned Into Google Driving Directions & Published as a Free eBook Ancient Rome’s System of Roads Visualized in the Style of Modern Subway Maps If You Drive Down a Stretch of Route 66, the Road Will Play “America the Beautiful” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:02p | To Read This Experimental Edition of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, You’ll Need to Add Heat to the Pages The Jan van Eyck Academie, a "multiform institute for fine art, design and reflection" in Holland, has come up with a novel way of presenting Ray Bradbury's 1953 work of dystopian fiction, Fahrenheit 451. On Instagram, they write:

Want to see how the novel unfolds? Just add heat. That's the idea. Apparently they actually have plans to market the book. When asked on Instagram, "How can I purchase one of these?," they replied "We're working on it! Stay tuned." When that day comes, please handle the book with care. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: Who Was Afraid of Ray Bradbury & Science Fiction? The FBI, It Turns Out (1959) Ray Bradbury: “I Am Not Afraid of Robots. I Am Afraid of People” (1974) Ray Bradbury: Literature is the Safety Valve of Civilization To Read This Experimental Edition of Ray Bradbury’s <i>Fahrenheit 451</i>, You’ll Need to Add Heat to the Pages is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/10/12 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |