[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, November 22nd, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | Expensive Wine Is for Dupes: Scientific Study Finds No Strong Correlation Between Quality & Price If wine is on your Thanksgiving menu tomorrow, then keep this scientific finding in mind: According to a 2008 study published in the Journal of Wine Economics, the quality of wine doesn't generally correlate with its price. At least not for most people. Written by researchers from Yale, UC Davis and the Stockholm School of Economics, the abstract for the study states:

You can read online the complete study, "Do More Expensive Wines Taste Better? Evidence from a Large Sample of Blind Tastings." But if you're looking for something that puts the science into more quotidien English and makes the larger case for keeping your hard-earned cash, watch the video from Vox above. Related Content: The Oldest Unopened Bottle of Wine in the World (Circa 350 AD) Vintage Wine in our Collection of 1100 Free Online Courses The Corkscrew: The 700-Pound Mechanical Sculpture That Opens a Wine Bottle & Pours the Wine Expensive Wine Is for Dupes: Scientific Study Finds No Strong Correlation Between Quality & Price is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

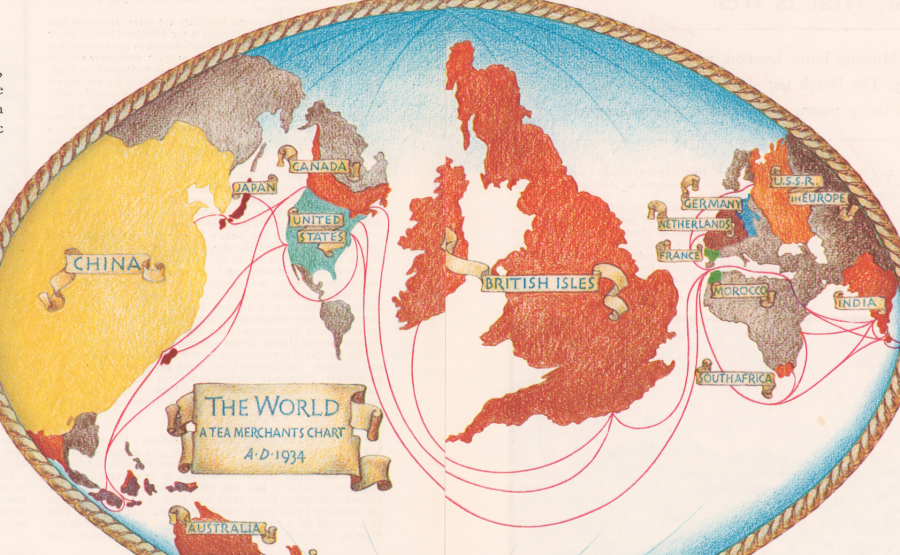

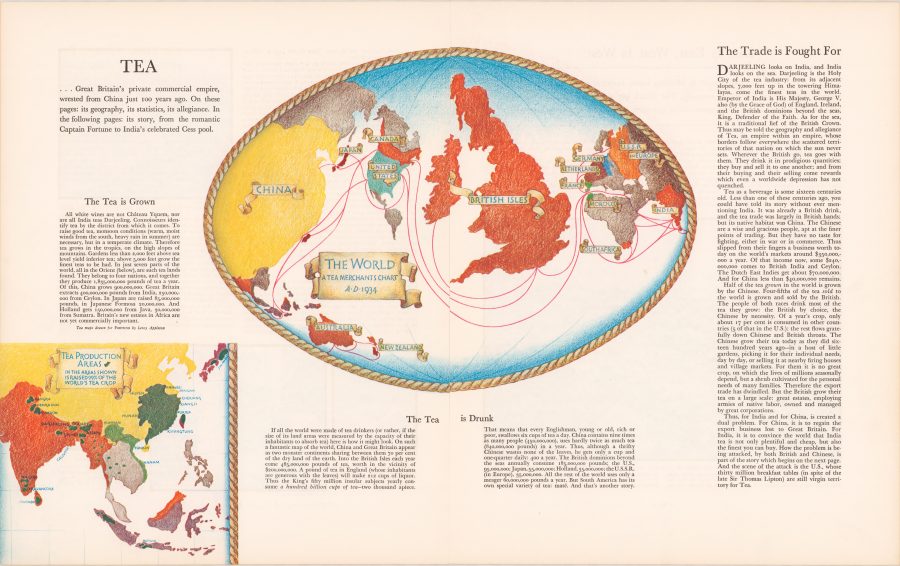

| 12:00p | 1934 Map Resizes the World to Show Which Country Drinks the Most Tea

Not a day goes by that I don’t use Google Maps for something or other, whether it’s basic navigation, researching an address, or finding a dry cleaner. Though some of us might resent the dominance such mapping technology has over our daily interactions, there’s no denying its endless utility. But maps can be so much more than useful tools for getting around—they are works of art, thought experiments, imaginative flights of fancy, and data visualization tools, to name but a few of their overlapping functions. For the imperialists of previous ages, maps displayed a mastery of the world, whether cataloguing travel times from London to everywhere else on the globe, or—as in the example we have here—resizing countries according to how much tea their people drank. But this is not a map we should look to for accuracy. Like many such cartographic data charts, it promotes a particular agenda. “George Orwell once wrote that tea was one of the mainstays of civilization,” notes Jack Goodman at Atlas Obscura. “Tea, asserted Orwell, has the power to make one feel braver, wiser, and more optimistic. The man spoke for a nation.” (And he spoke to a nation in a 1946 Evening Standard essay, “A Nice Cup of Tea.”) From the map above, titled “The Tea is Drunk” and published by Fortune Magazine in 1934, we learn, writes Goodman, that “Britain consumed 485,000 pounds of tea per year. That’s one hundred billion cups of tea, or around six cups a day for each person.” We might note however, that “the population of China was then nine times bigger than that of the U.K., and they drank roughly twice as much tea as the Brits did.” Why isn’t China at the center of the map? “The author made a tenuous point about the cultural differences between the two: the Chinese drank tea as a necessity, the British by choice.”

Cornell University library’s description of the map is more forthright: “While China actually consumed twice as much tea as Britain, its position at the edge of the map assured that the focus will be on the British Isles.” That focus is commercial in nature, meant to encourage and inform British tea merchants for whom tea was more than a beverage; it was one of the nation's pre-eminent commodities, though most of what was sold as a national product was Indian tea grown in India. Yet the map brims with pride in the British tea trade. “Thus may be told the geography and allegiance of Tea,” its author proclaims, “an empire within an empire, whose borders follow everywhere the scattered territories of that nation on which the sun never sets.” A little over a decade later, India won its independence, and the empire began to fall apart. But the British never lost their taste for or their national pride in tea. View and download a high-resolution scan of the "Tea is Drunk" map at the Cornell Library site. via Atlas Obscura Related Content: George Orwell Explains How to Make a Proper Cup of Tea 10 Golden Rules for Making the Perfect Cup of Tea (1941) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness 1934 Map Resizes the World to Show Which Country Drinks the Most Tea is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

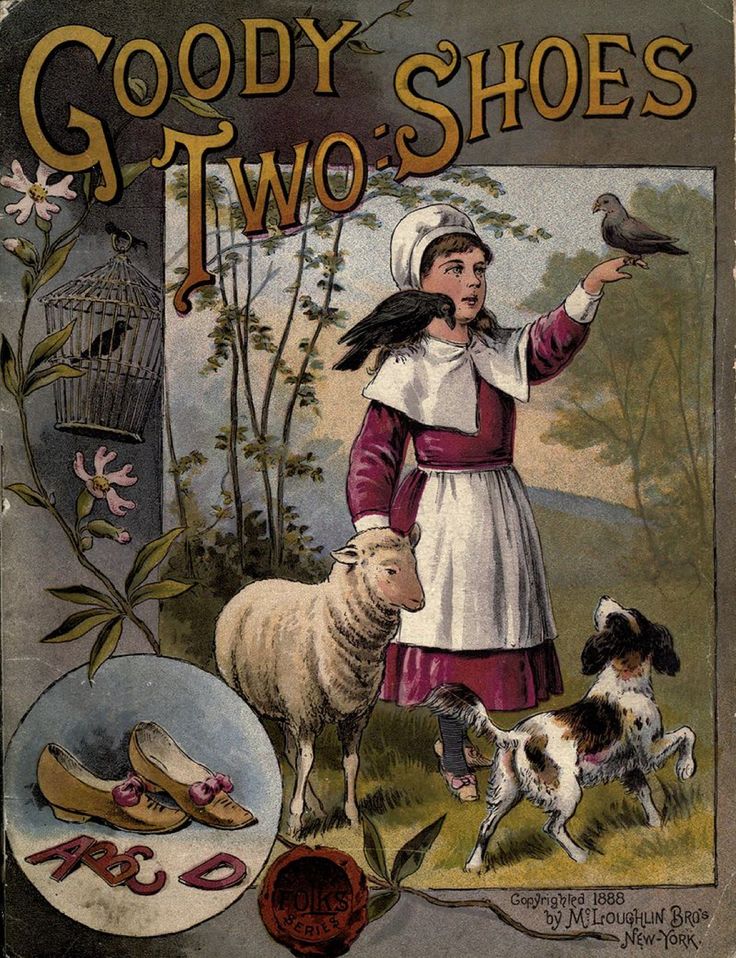

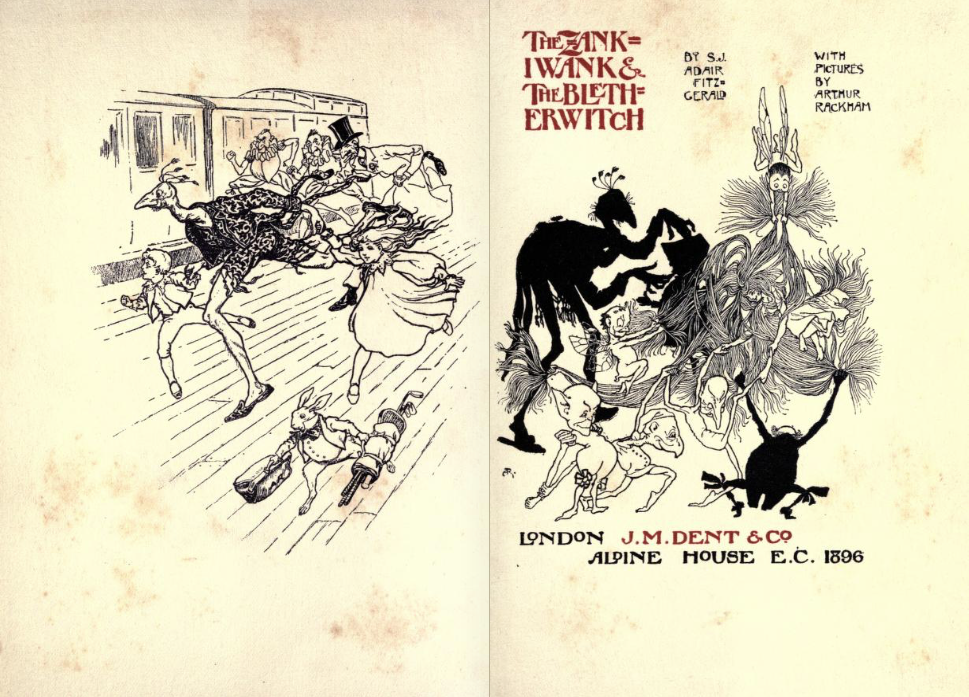

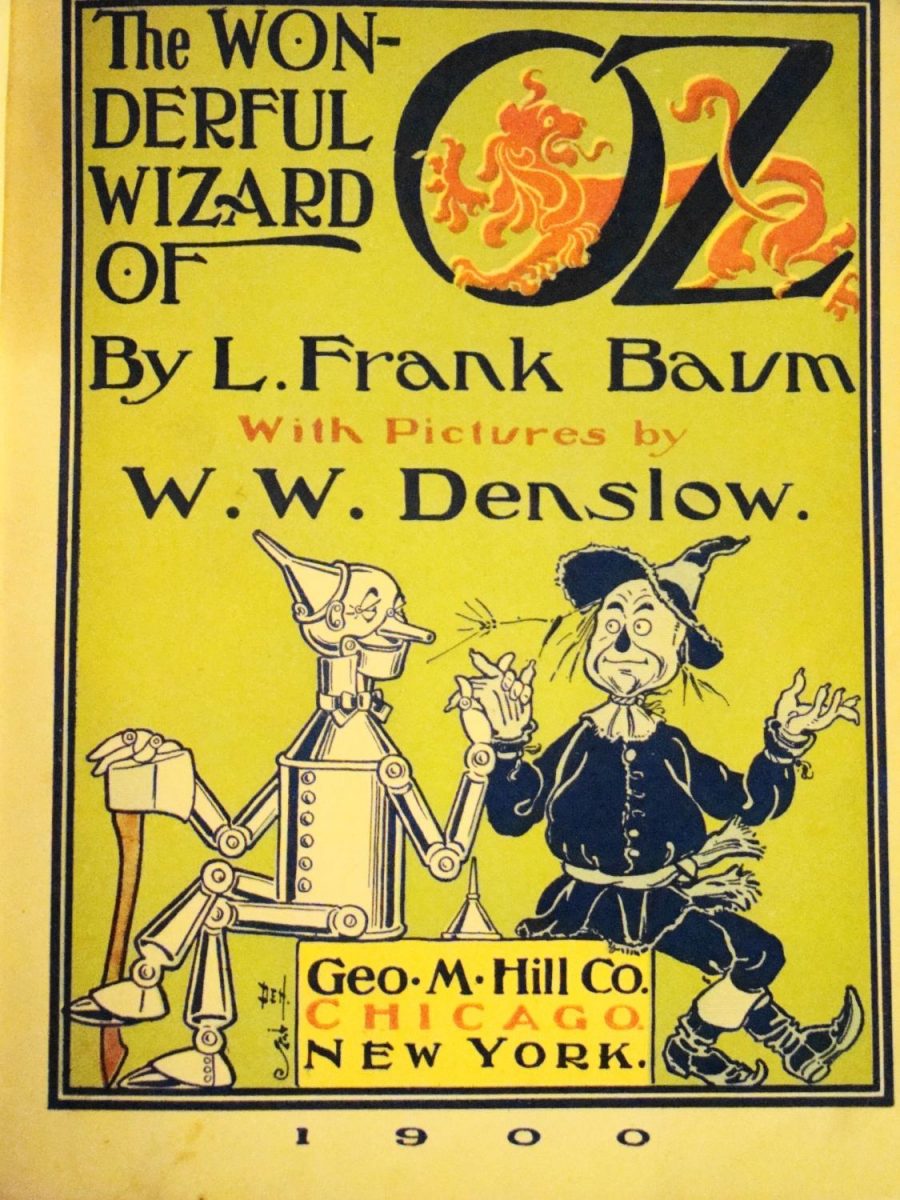

| 3:00p | A Digital Archive of 1,800+ Children’s Books from UCLA

In the early 18th century, the novel was seen as a frivolous and trivial form at best, a morally corrupting one at worst. Given that the primary readers of novels were women, the belief smacks of patriarchal condescension and a kind of thought control. Fiction is a place where readers can imaginatively live out fantasies and tragedies through the eyes of an imagined other. Respectable middle-class women were expected instead to read conduct manuals and devotionals. English novelist Samuel Richardson sought to bring respectability to his art in the form of Pamela in 1740, a novel which began as a conduct manual and whose subtitle rather bluntly states the moral of the story: “Virtue Rewarded.” This moralizing expressed itself in another literary form as well. Children’s books, such as there were, also tended toward the moralistic and didactic, in attempts to steer their readers away from the dangers of what was then called “enthusiasm.”

“Prior to the mid-eighteenth century,” notes the UCLA Children’s Book Collection—a digital repository of over 1800 children’s books dating from 1728 to 1999—“books were rarely created specifically for children, and children’s reading was generally confined to literature intended for their education and moral edification rather than for their amusement. Religious works, grammar books, and ‘courtesy books’ (which offered instruction on proper behavior) were virtually the only early books directed at children.” But a change was in the making in the middle of the century.

Pamela attracted a ribald, even pornographic, response—most notably in Henry Fielding’s satire An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews and the Marquis de Sade’s Justine Meamwhile, the world of children’s literature also underwent a radical shift. “The notion of pleasure in learning was becoming more widely accepted.” Illustrations, previously “consisting of small woodcut vignettes,” slowly began to move to the fore, and “innovations in typography and printing allowed greater freedom in reproducing art.”

That’s not to say that the didactic attitude was dispelled—we see codes of conduct and overt religious themes embedded in children’s literature throughout the 19th century. But as we pointed out in a post on another children’s book archive from the University of Florida, the more staid and traditional books increasingly competed with adventure stories, works of fantasy, and what we call today Young Adult literature like that of Mark Twain and Louisa May Alcott. You can see this tension in the UCLA collection, between pleasure and duty, leisure and work, and education as moral and social training and as a means of achieving personal freedom. Of the adult literary imagination of the time, Leo Bersani writes in A Future for Astyanax that “the confrontation in nineteenth-century works between a structured, socially viable and verbally analyzable self and the wish to shatter psychic and social structures produces considerable stress and conflict.” I think we can see a similar conflict, expressed much more playfully, in books for children of the past two hundred years or so. Enter the UCLA collection, which includes not only historic children's books but present-day exhibit catalogs and more, here. Related Content: Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online The First Children’s Picture Book, 1658’s Orbis Sensualium Pictus The Anti-Slavery Alphabet: 1846 Book Teaches Kids the ABCs of Slavery’s Evils Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness A Digital Archive of 1,800+ Children’s Books from UCLA is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

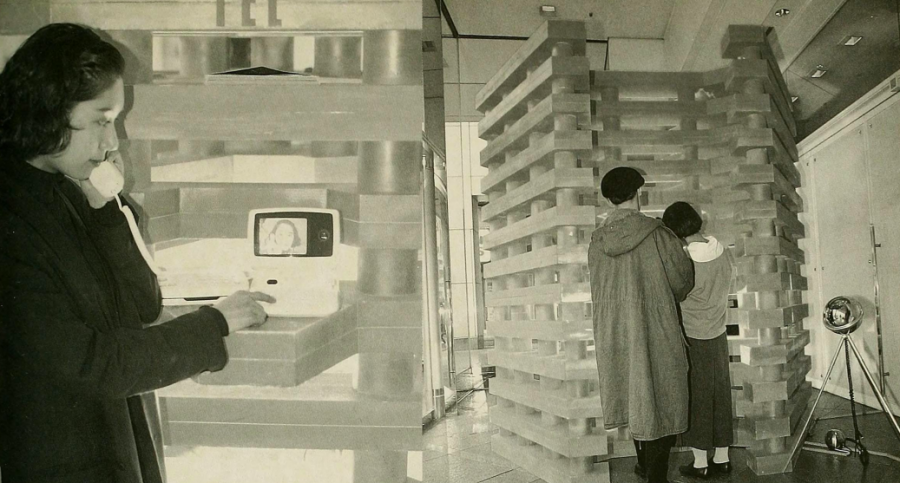

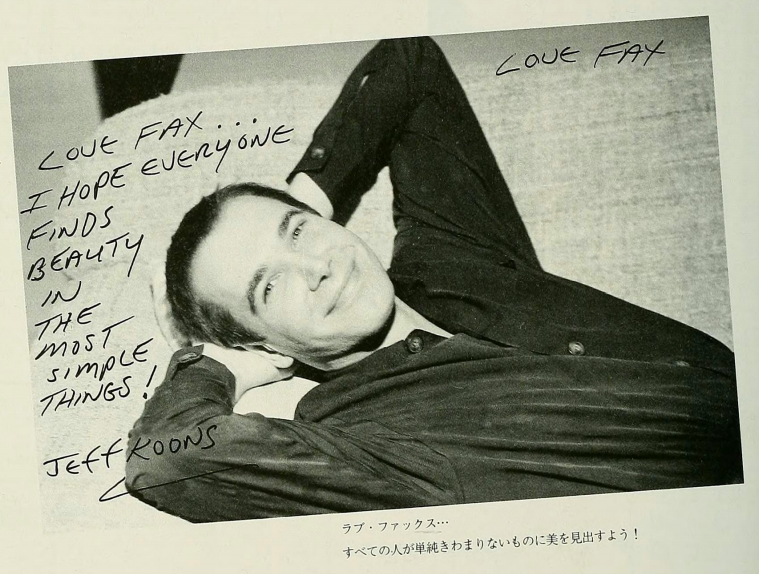

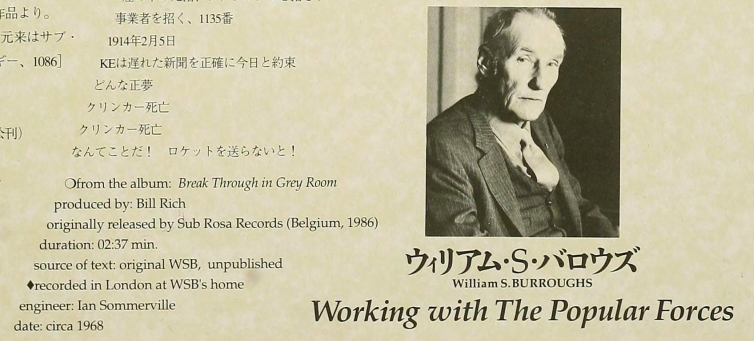

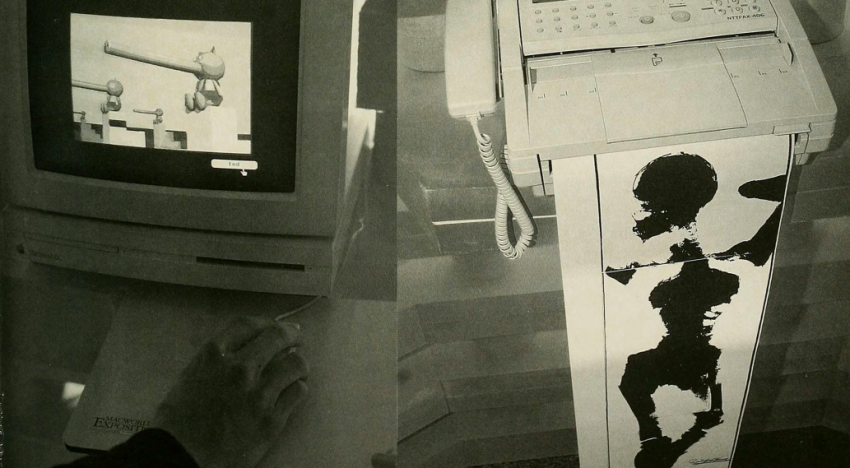

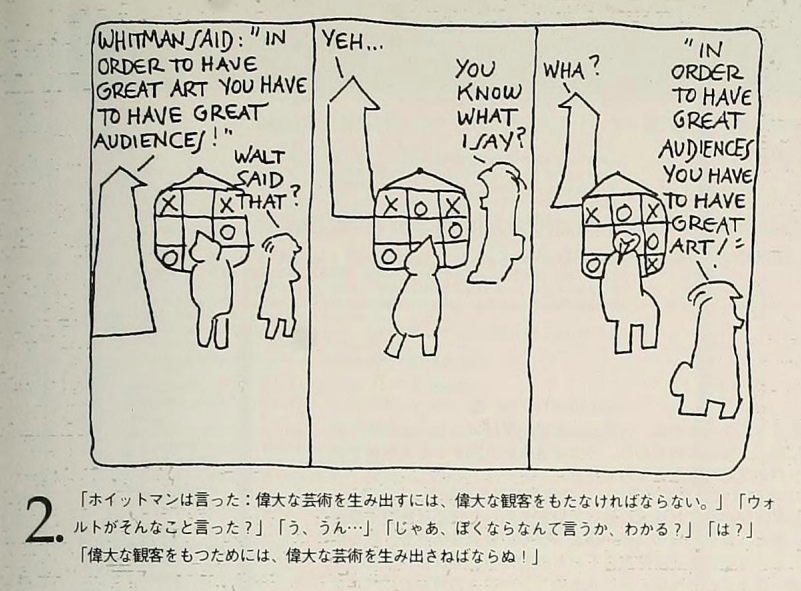

| 6:00p | The 1991 Tokyo Museum Exhibition That Was Only Accessible by Telephone, Fax & Modem: Features Works by Laurie Anderson, John Cage, William S. Burroughs, J.G. Ballard & Merce Cunningham

The deeper we get into the 21st century, the more energy and resources museums put into digitizing their offerings and making them available, free and worldwide, as virtual experiences on the internet. But what form would a virtual museum have taken before the internet as we know it today? Japanese telecommunications giant NTT (best known today in the form of the cellphone service provider NTT DoCoMo) developed one answer to that question in 1991: The Museum Inside the Telephone Network, an elaborate art exhibit accessible nowhere in the physical world but everywhere in Japan by telephone, fax, and even — in a highly limited, pre-World-Wide-Web fashion — computer modem.

"The works and messages from almost 100 artists, writers, and cultural figures were available through five channels," says Monoskop, where you can download The Museum Inside the Telephone Network's catalog (also available in high resolution). "The works in 'Voice & sound channel' such as talks and readings on the theme of communication could be listened to by telephone. The 'Interactive channel' offered participants to create musical tunes by pushing buttons on a telephone. Works of art, novels, comics and essays could be received at home through 'Fax channel.' The 'Live channel' offered artists’ live performances and telephone dialogues between invited intellectuals to be heard by telephone. Additionally, computer graphics works could be accessed by modem and downloaded to one’s personal computer screen for viewing."

"We need to recognize honestly that there were numerous problems with The Museum Inside the Telephone Network," writes curator and critic Asada Akira in the catalog's introduction. "Neither the preparation time nor the means for carrying it out was sufficient. Thus there were not a few creative artists whose participation would have been a great asset to the project, but whom we were forced to do without." Yet its list of contributors, which still reads like a Who's-Who of the avant-garde and otherwise adventurous creators of the day, includes architects like Isozaki Arata and Renzo Piano, musicians like Laurie Anderson and Sakamoto Ryuichi, directors like Kurosawa Kiyoshi and Derek Jarman, writers like William S. Burroughs and J.G. Ballard, composers like John Cage and Philip Glass, choreographers like William Forsythe, Merce Cunningham, and visual artists like Yokoo Tadanori and Jeff Koons.

The Museum Inside the Telephone Network launched as the first venture of NTT's InterCommunication Center (ICC), a "21st-century museum that will provide interface between science and technology and art and culture in the coming electronic age," as Asada described it in 1991. Having recently celebrated its 20th year open in Tokyo's Opera City Tower, the ICC continues to put on a variety of non-virtual exhibitions very much in the spirit of the original, and involving some of the very same artists as well (as of this writing, they're readying a music installation co-created by Sakamoto). But offline or on, any union of art and technology is only as interesting as the spirit motivating it, and the creators of such projects would do well to keep in mind the words of The Museum Inside the Telephone Network contributor Kondou Kouji: "I hope that people will think of this as the experience of accidentally drifting into a telephone network, wherein awaits a vast world of pleasure and fun."

Related Content: Take a Virtual Tour of the 1913 Exhibition That Introduced Avant-Garde Art to America Take a Virtual Reality Tour of the World’s Stolen Art Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The 1991 Tokyo Museum Exhibition That Was Only Accessible by Telephone, Fax & Modem: Features Works by Laurie Anderson, John Cage, William S. Burroughs, J.G. Ballard & Merce Cunningham is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/11/22 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |