[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, December 6th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | The Vibrant Color Wheels Designed by Goethe, Newton & Other Theorists of Color (1665-1810)

Maybe it’s the cloistered headiness of Rene Descartes, or the rigorous austerity of Isaac Newton; maybe it’s all the leathern breaches, gray waistcoats, sallow faces, and powdered wigs… but we tend not to associate Enlightenment Europe with an explosion of color theory. Yet, philosophers of the late 17th and 18th centuries were obsessed with light and sight. Descartes wrote a treatise on optics, as did Newton. Newton first described in his 1672 Opticks the “revolutionary new theory of light and colour,” the University of Cambridge Whipple Library writes, “in which he claimed that experiments with prisms proved that white light was comprised of light of seven distinct colours.” Scientists debated Newton’s theory “well into the 19th century.”

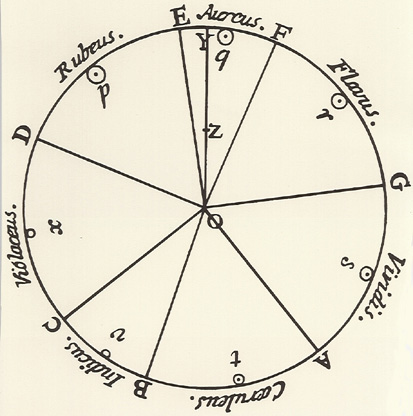

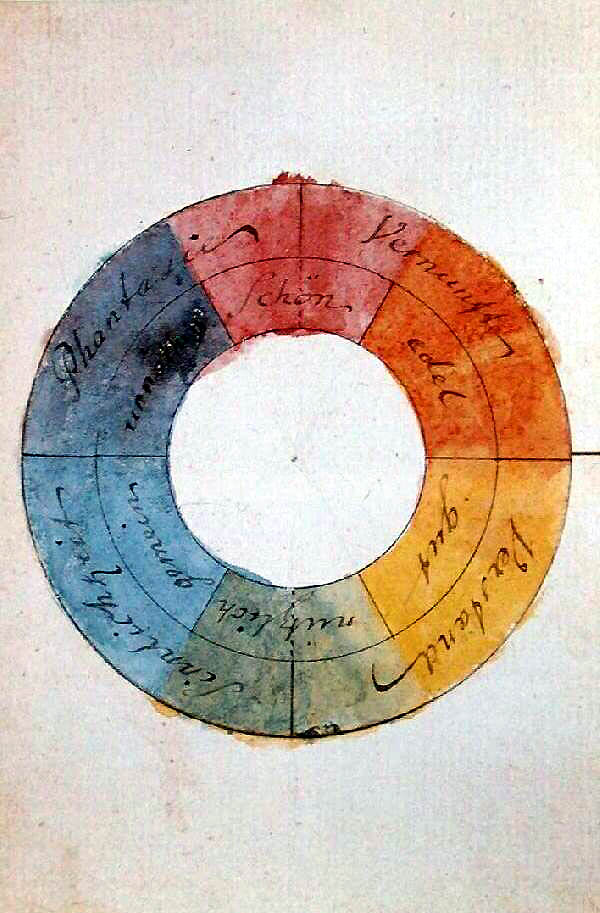

One early opponent famously illustrated his rebuttal. Poet, writer, and scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published Theory of Colors (see here), with its carefully hand-drawn and colored diagrams and wheels, in 1809. From Newton's time onward, color theorists elaborated prevailing concepts with color wheels, the first attributed to Newton in 1704 (and drawn in black and white, above).

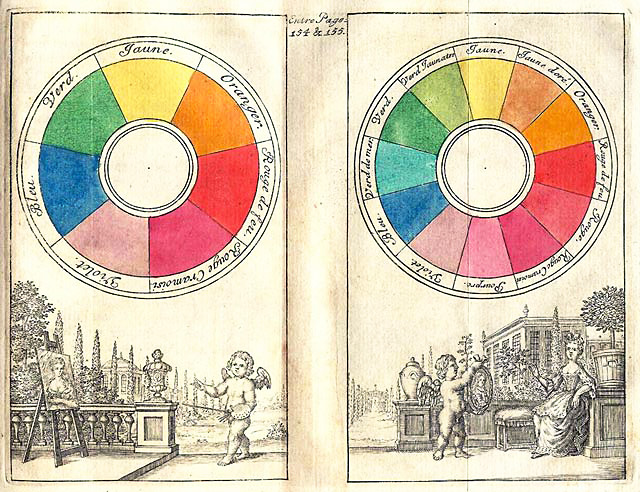

Newton’s wheel “arranged red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet into a natural progression on a rotating disk.” Four years later, painter Claude Boutet made his 7-color and 12-color circles (top), based on Newton’s theories. Artists, chemists, mapmakers, poets, even entomologists… everyone seemed to have a pet theory of color, generally accompanied by elaborate colored charts and diagrams.

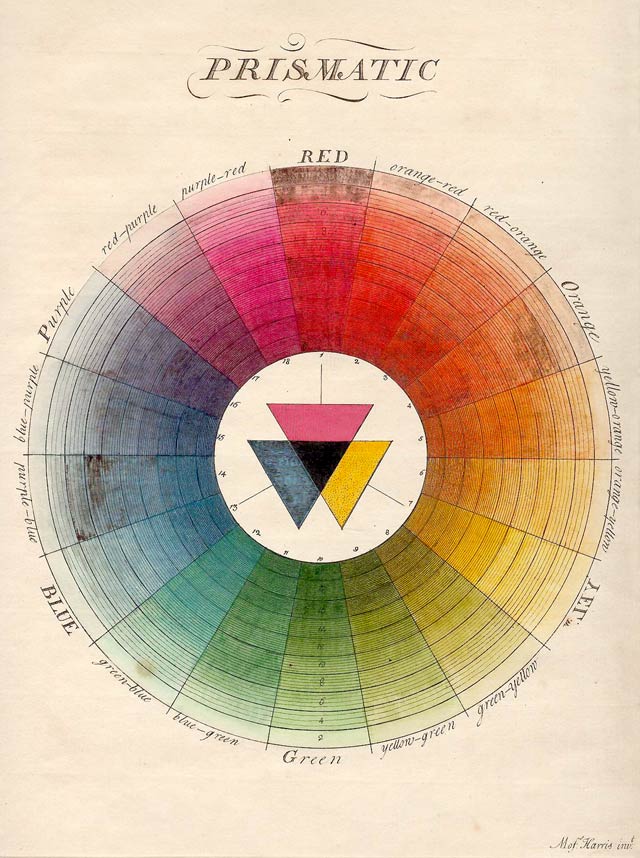

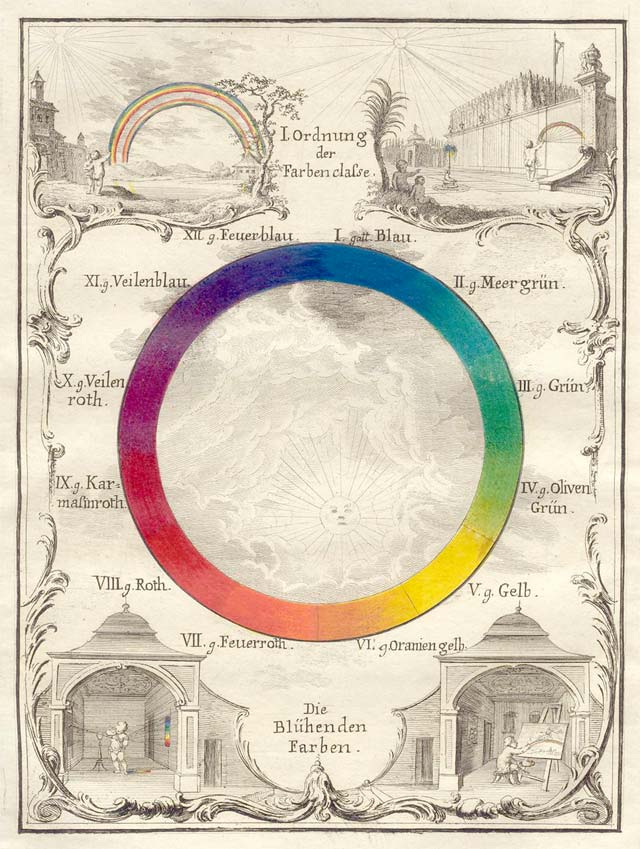

The color wheel was one among many forms—which often presented contrasting theories, like that of Jacques-Fabien Gautier, who argued that black and white were primary colors. But the wheel, and Newton’s basic ideas about it, have endured almost unchanged. The wheel further up (third one from top) by British entomologist Moses Harris from 1776 shows Newton’s 7-color scheme simplified to the 6 primary and secondary colors we usually see, arranged in the complementary and analogous scheme, with tertiary gradations between them. Another entomologist, Ignaz Schiffermüller, drew the 12-color wheel right above.

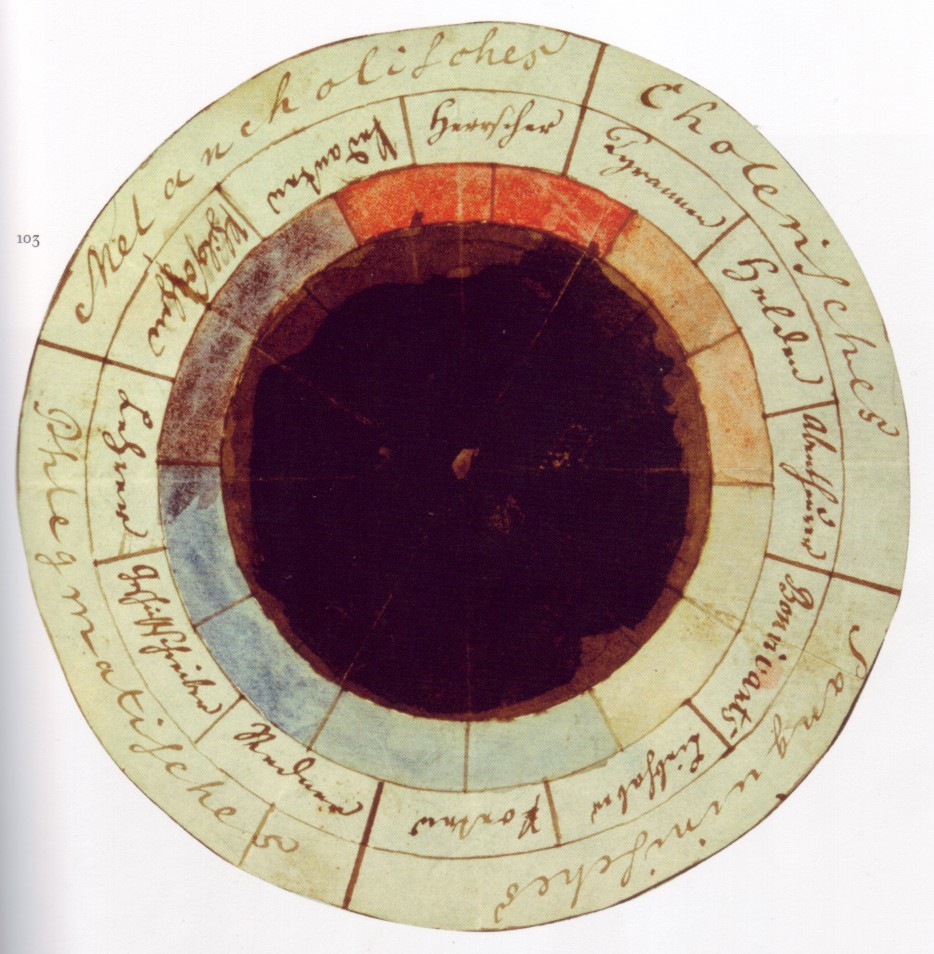

Color is always representative. Newton’s original wheel included “musical notes correlated with color.” By the end of the 18th century, color theory had become increasingly tied to psychological theories and typologies, as in the wheel above, the “rose of temperaments,” made by Goethe and Friedrich Schiller in 1789 to illustrate “human occupations and character traits,” the Public Domain Review notes, including “tyrants, heroes, adventurers, hedonists, lovers, poets, public speakers, historians, teachers, philosophers, pedants, rulers,” grouped into the four temperaments of humoral theory.

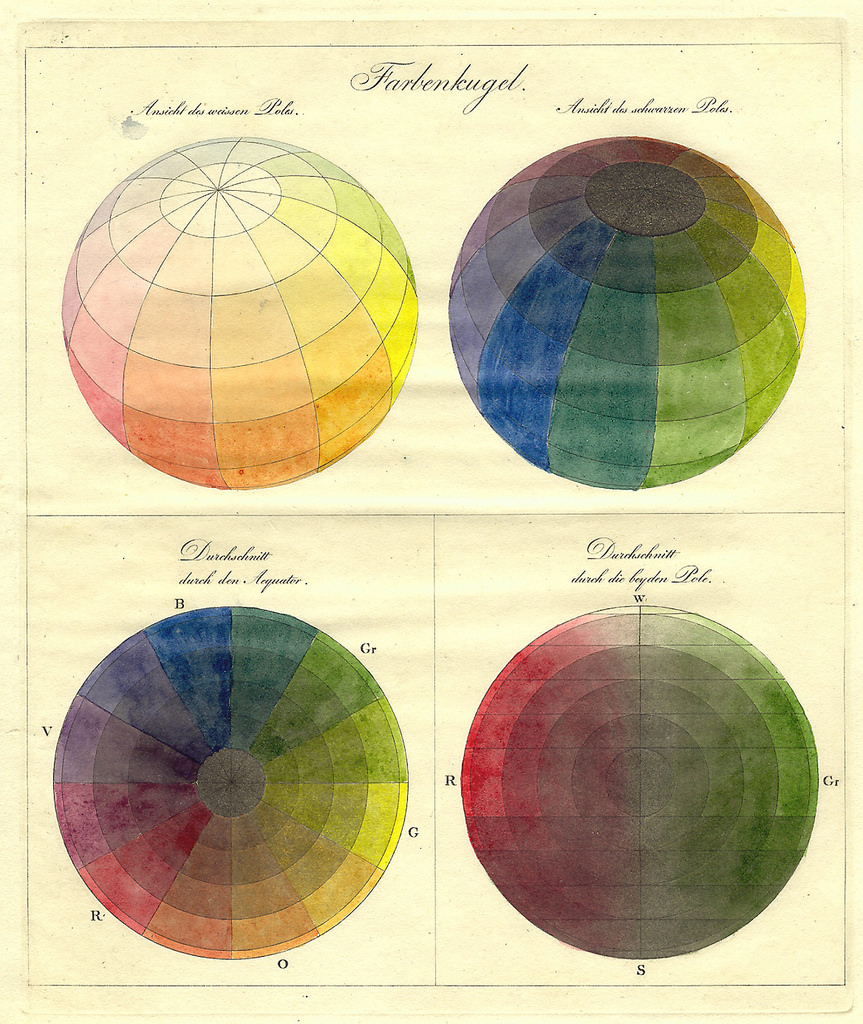

It’s a fairly short leap from these psychologies of color to those used by advertisers and commercial designers in the 20th century—or from the artists and scientists’ color theories to abstract expressionism, the Bauhaus school, and the chemists and photographers who recreated the colors of the world on film. (Goethe's color wheel, below, from Theory of Color, illustrates his chapter on "Allegorical, symbolic, and mystical use of colour.") See more early color wheels, like Philipp Otto Runge's 1810 Farbenkugel, as well as other conceptual color schemes, at the Public Domain Review.

Related Content: Goethe’s Theory of Colors: The 1810 Treatise That Inspired Kandinsky & Early Abstract Painting How Technicolor Revolutionized Cinema with Surreal, Electric Colors & Changed How We See Our World A Pre-Pantone Guide to Colors: Dutch Book From 1692 Documents Every Color Under the Sun Sir Isaac Newton’s Papers & Annotated Principia Go Digital Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Vibrant Color Wheels Designed by Goethe, Newton & Other Theorists of Color (1665-1810) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | How Scientology Works: A Primer Based on a Reading of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Film, The Master Paul Thomas Anderson's The Master focuses, with almost unbearable intensity, on two characters: Joaquin Phoenix's impulsive ex-sailor Freddie Quell, and Philip Seymour Hoffman's Lancaster Dodd, "the founder and magnetic core of the Cause — a cluster of folk who believe, among other things, that our souls, which predate the foundation of the Earth, are no more than temporary residents of our frail bodily housing," writes The New Yorker's Anthony Lane in his review of the film. "Any relation to persons living, dead, or Scientological is, of course, entirely coincidental." Before The Master came out, rumor built up that the film mounted a scathing critique of the Church of Scientology; now, we know that it accomplishes something, par for the course for Anderson, much more fascinating and artistically idiosyncratic. Few of its gloriously 65-millimeter-shot scenes seem to have much to say, at least directly, about Scientology or any other system of thought. But perhaps the most memorable, in which Dodd, having discovered Freddie stown away aboard his chartered yacht, offers him a session of "informal processing," does indeed have much to do with the faith founded by L. Ron Hubbard — at least if you believe the analysis of Evan Puschak, better known as the Nerdwriter, who argues that the scene "bears an unmistakable reference to a vital activity within Scientology called auditing." Just as Dodd does to Freddie, "the auditor in Scientology asks questions of the 'preclear' with the goal of ridding him of 'engrams,' the term for traumatic memory stored in what's called the 'reactive mind.'" By thus "helping the preclear relive the experience that caused the trauma," the auditor accomplishes a goal that, in a clip Puschak includes in the essay, Hubbard lays out himself: to "show a fellow that he's mocking up his own mind, therefore his own difficulties; that he is not completely adrift in, and swamped by, a body." Scientological or not, such notions do intrigue the desperate, drifting Freddie, and although the story of his and Dodd's entwinement, as told by Anderson, still divides critical opinion, we can say this for sure: it beats Battlefield Earth. Related Content: When William S. Burroughs Joined Scientology (and His 1971 Book Denouncing It) Space Jazz, a Sonic Sci-Fi Opera by L. Ron Hubbard, Featuring Chick Corea (1983) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. How Scientology Works: A Primer Based on a Reading of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Film, <i>The Master</i> is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:12p | The Van Gogh of Microsoft Excel: How a Japanese Retiree Makes Intricate Landscape Paintings with Spreadsheet Software Just when you thought you've mastered Microsoft Excel--creating pivot tables, VLOOKUPs and the rest--you discover the feature you never knew was there. The one that lets you create Japanese landscape paintings. When Tatsuo Horiuchi retired, he found that feature and leaned on it, hard. Now 77 years old, he has enough landscape paintings to stage an exhibition--all made with the point and click of a mouse. So what's the moral of this story? Maybe it's you're never too old to make art. Or maybe it's never too late to master those hidden features and push technology to the bleeding edge. In Tatsuo's case, he's doing both. Related Content: The Art of Hand-Drawn Japanese Anime: A Deep Study of How Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira Uses Light A Hypnotic Look at How Japanese Samurai Swords Are Made Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600-1915) Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints The Van Gogh of Microsoft Excel: How a Japanese Retiree Makes Intricate Landscape Paintings with Spreadsheet Software is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:00p | Why Incompetent People Think They’re Amazing: An Animated Lesson from David Dunning (of the Famous “Dunning-Kruger Effect”) The business world has long had special jargon for the Kafkaesque incompetence bedeviling the ranks of upper management. There is “the Peter principle,” first described in a satirical book of the same name in 1968. More recently, we have the positive notion of “failing upward.” The concept has inspired a mantra, “fail harder, fail faster,” as well as popular books like The Gift of Failure. Famed research professor, author, and TED talker Brené Brown has called TED “the failure conference," and indeed, a “FailCon” does exist, “in over a dozen cities on 6 continents around the globe.” The candor about this most unavoidable of human phenomena may prove a boon to public health, lowering levels of hypertension by a significant margin. But is there a danger in praising failure too fervently? (Samuel Beckett’s quote on the matter, beloved by many a 21st century thought leader, proves decidedly more ambiguous in context.) Might it present an even greater opportunity for people to “rise to their level of incompetence”? Given the prevalence of the “Dunning-Kruger Effect,” a cognitive bias explained by John Cleese in a previous post, we may not be well-placed to know whether our efforts constitute success or failure, or whether we actually have the skills we think we do. First described by social psychologists David Dunning (University of Michigan) and Justin Kruger (N.Y.U.) in 1999, the effect “suggests that we’re not very good at evaluating ourselves accurately.” So says the narrator of the TED-Ed lesson above, scripted by Dunning and offering a sober reminder of the human propensity for self-delusion. “We frequently overestimate our own abilities,” resulting in widespread “illusory superiority” that makes “incompetent people think they’re amazing.” The effect greatly intensifies at the lower end of the scale; it is often “those with the least ability who are most likely to overrate their skills to the greatest extent.” Or as Cleese plainly puts it, some people “are so stupid, they have no idea how stupid they are.” Combine this with the converse effect—the tendency of skilled individuals to underrate themselves—and we have the preconditions for an epidemic of mismatched skill sets and positions. But while imposter syndrome can produce tragic personal results and deprive the world of talent, the Dunning-Kruger effect’s worst casualties affect us all adversely. People “measurably poor at logical reasoning, grammar, financial knowledge, math, emotional intelligence, running medical lab tests, and chess all tend to rate their expertise almost as favorably as actual experts do.” When such people get promoted up the chain, they can unwittingly do a great deal of harm. While arrogant self-importance plays its role in fostering delusions of expertise, Dunning and Kruger found that most of us are subject to the effect in some area of our lives simply because we lack the skills to understand how bad we are at certain things. We don't know the rules well enough to successfully, creatively break them. Until we have some basic understanding of what constitutes competence in a particular endeavor, we cannot even understand that we’ve failed. Real experts, on the other hand, tend to assume their skills are ordinary and unremarkable. “The result is that people, whether they’re inept or highly skilled, are often caught in a bubble of inaccurate self-perception." How can we get out? The answers won’t surprise you. Listen to constructive feedback and never stop learning, behavior that can require a good deal of vulnerability and humility. Related Content: The Power of Empathy: A Quick Animated Lesson That Can Make You a Better Person Free Online Psychology & Neuroscience Courses Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Why Incompetent People Think They’re Amazing: An Animated Lesson from David Dunning (of the Famous “Dunning-Kruger Effect”) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/12/06 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |