[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, December 18th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 12:00p | The Doodles in Leonardo da Vinci’s Manuscripts Contain His Groundbreaking Theories on the Laws of Friction, Scientists Discover

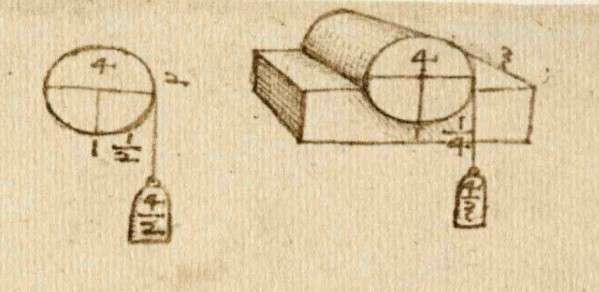

Just like the rest of us, Leonardo da Vinci doodled and scribbled: you can see it in his digitized notebooks, which we featured this past summer. But the prototypical Renaissance man, both unsurprisingly and characteristically, took that scribbling and doodling to a higher level entirely. Not only do his margin notes and sketches look far more elegant than most of ours, some of them turn out to reveal his previously unknown early insight into important subjects. Take, for instance, the study of friction (otherwise known as tribology), which may well have got its start in what at first just looked like doodles of blocks, weights, and pulleys in Leonardo's notebooks. This discovery comes from University of Cambridge engineering professor Ian M. Hutchings, whose research, says that department's site, "examines the development of Leonardo's understanding of the laws of friction and their application. His work on friction originated in studies of the rotational resistance of axles and the mechanics of screw threads, but he also saw how friction was involved in many other applications." One page, "from a tiny notebook (92 x 63 mm) now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, dates from 1493" and "contains Leonardo’s first statement of the laws of friction," sketches of "rows of blocks being pulled by a weight hanging over a pulley – in exactly the same kind of experiment we might do today to demonstrate the laws of friction."

"While it may not be possible to identify unequivocally the empirical methods by which Leonardo arrived at his understanding of friction," Hutchings writes in his paper, "his achievements more than 500 years ago were outstanding. He made tests, he observed, and he made powerful connections in his thinking on this subject as in so many others." By the year of these sketches Leonardo "had elucidated the fundamental laws of friction," then "developed and applied them with varying degrees of success to practical mechanical systems." And though tribologists had no idea of Leonardo's work on friction until the twentieth century, seemingly unimportant drawings like these show that he "stands in a unique position as a quite remarkable and inspirational pioneer of tribology." What other fields of inquiry could Leonardo have pioneered without history having properly acknowledged it? Just as his life inspires us to learn and invent, so research like Hutchings' inspires us to look closer at what he left behind, especially at that which our eyes may have passed over before. You can open up Leonardo's notebooks and have a look yourself. Just make sure to learn his mirror writing first. Related Content: Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages Leonardo da Vinci’s Bizarre Caricatures & Monster Drawings Leonardo Da Vinci’s To Do List (Circa 1490) Is Much Cooler Than Yours Download the Sublime Anatomy Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci: Available Online, or in a Great iPad App Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Doodles in Leonardo da Vinci’s Manuscripts Contain His Groundbreaking Theories on the Laws of Friction, Scientists Discover is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | Thelonious Monk’s 25 Tips for Musicians (1960)

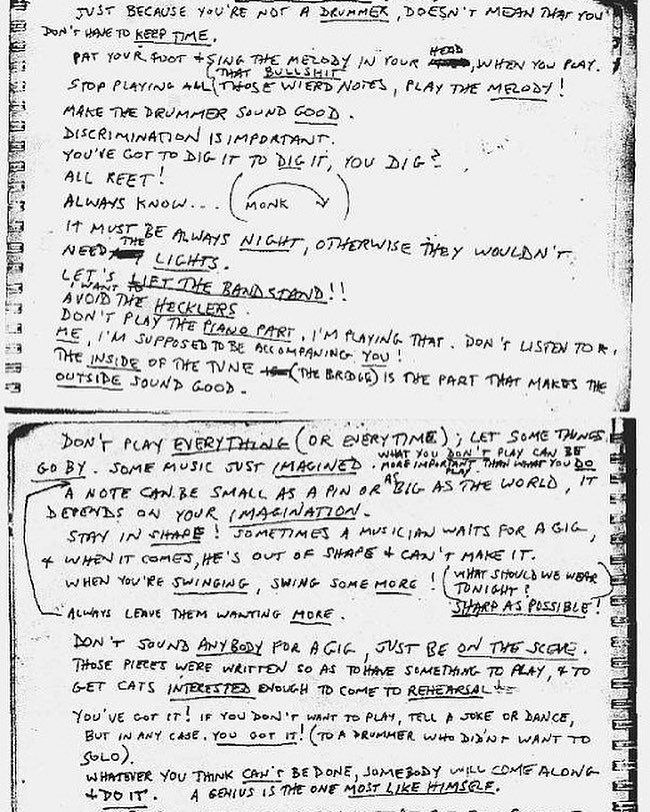

Stories of idiosyncratic and demanding composers and bandleaders abound in mid-century jazz—of pioneers who pushed their musicians to new heights and in entirely new directions through seeming sheer force of will. Miles Davis’ name inevitably comes up in such discussions. Davis was “not a patient man,” jazz historian Dan Morgenstern remarks, “and I think he got impatient with himself just as he did with other people.” Jazz and other forms of music have been immeasurably enriched by that impatience. Other bop eccentrics—like John Coltrane—brought their own personality quirks and personal struggles to bear on their styles, pushing toward new insights and experiments that shaped the future of the music. Their peer Thelonious Monk, writes Candace Allen at The Guardian, “the jobbing musician who couldn’t, more than wouldn’t, conform to the conventions of the job," seemed the odd man out. He "spent most of his professional life struggling to support his family.” Monk's “misdiagnosed and ignorantly medicated bipolar condition” and his stubborn refusal to follow trends made it difficult for him to achieve the success he deserved. But it was Monk’s inability to do things any way but his way that made up the essence of his greatness—his insistence on “playing angular, spacious and ‘slow,’” his “daunting and mysterious” silences. A musical prodigy, Monk honed his piano chops in Baptist churches and New York rent parties before his residency as house pianist for Teddy Hill’s band at the famed Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, where he helped usher in the “bebop revolution.” While he “charted a new course for modern music few were willing to follow,” notes All About Jazz, those who did learned a new way of playing, Monk’s way. What does that mean? The list above, as transcribed by saxophonist Steve Lacy, lays it all out. “T. Monk’s Advice,” as it’s called, offers guidelines, pointers, and pointed commands. Some of these instructions relate directly to live performance (“don’t sound anybody for a gig, just be on the scene,” "avoid the hecklers"). Others get at the heart of Monk’s genius—his talent for creating space, both inside the arrangements and between the notes. Monk makes sure he’s the only one playing “weird notes,” demanding that musicians “play the melody!” “Don’t play the piano part,” he says, “I am playing that.” And he peppers the list with cryptic philosophical and social observations (“discrimination is important,” “always know,” “a genius is the one most like himself”). In the last item on the list (cut off in the image above), Monk veers sharply away from music with some humorous social commentary. It’s a move that’s typical Monk—both deeply serious and playful, entirely unexpected, and leaving us, as he instructs his musicians, “wanting more.” See a transcription of Monk's list of advice for musicians below.

via Lists of Note Related Content: Captain Beefheart Issues His “Ten Commandments of Guitar Playing” John Coltrane Draws a Mysterious Diagram Illustrating the Mathematical & Mystical Qualities of Music John Coltrane’s Handwritten Outline for His Masterpiece A Love Supreme (1964) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Thelonious Monk’s 25 Tips for Musicians (1960) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

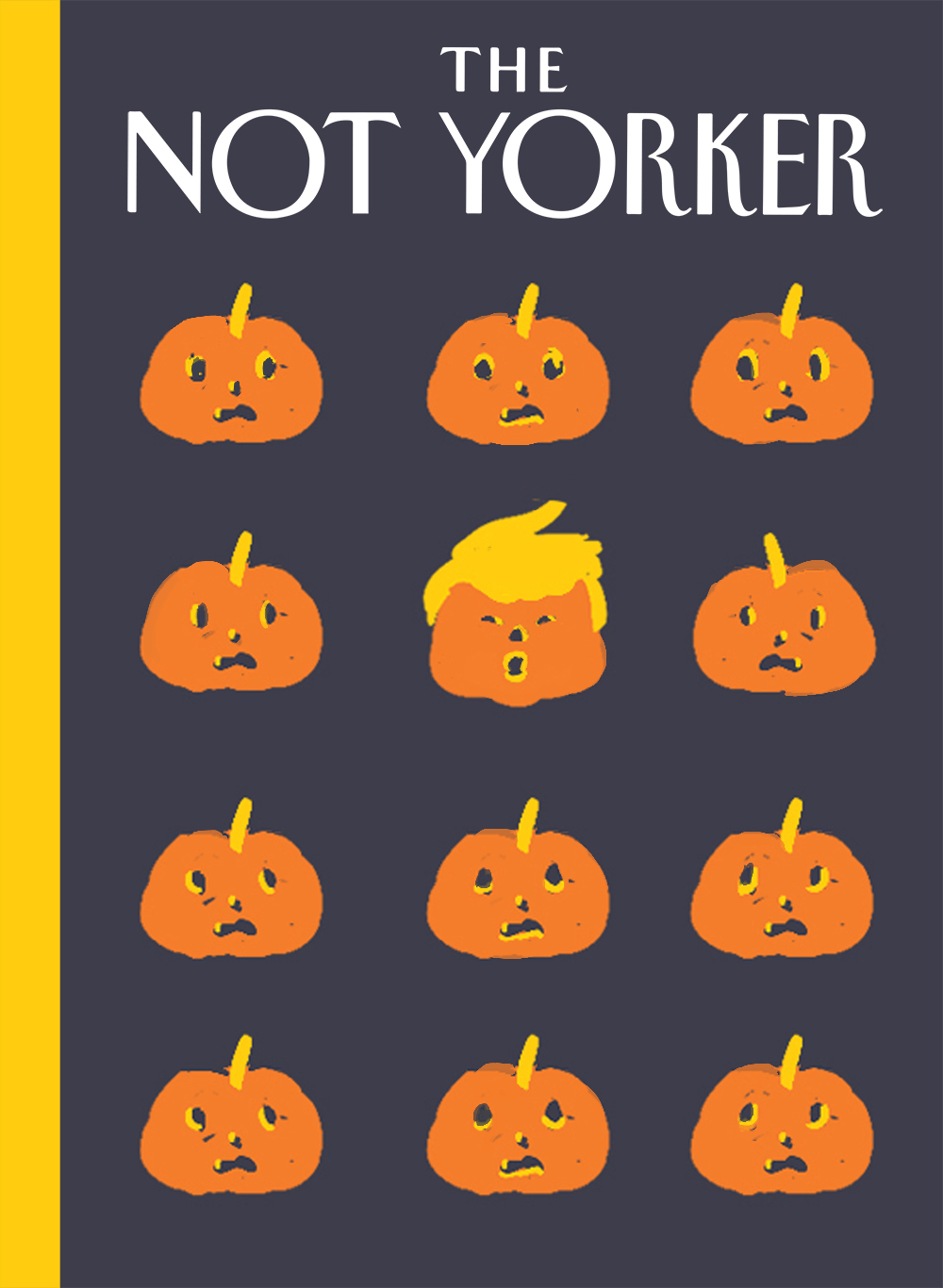

| 6:17p | The Not Yorker: A Collection of Rejected & Late Cover Submissions to The New Yorker

What's happened to the thousands of cover designs that have been submitted to The New Yorker? And then been rejected, either summarily or with much consideration? Probably most have faded into oblivion. But at least some are now seeing the light of day over at The Not Yorker, a web site that collects "declined or late cover submissions" to the storied magazine. See a gallery of declined illustrations here. The creators of the new site encourage illustrators to submit their rejected covers here. And lest there be any doubt, The Not Yorker is not officially affiliated with The New Yorker. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content The Tokyoiter: Artists Pay Tribute to the Japanese Capital with New Yorker-Style Magazine Covers Download a Complete, Cover-to-Cover Parody of The New Yorker: 80 Pages of Fine Satire The New Yorker’s Fiction Podcast: Where Great Writers Read Stories by Great Writers <i>The Not Yorker</i>: A Collection of Rejected & Late Cover Submissions to <i>The New Yorker</i> is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00p | Read the “Don’t Let the Bastards Get You Down” Letter That Albert Einstein Sent to Marie Curie During a Time of Personal Crisis (1911)

Marie Curie’s 1911 Nobel Prize win, her second, for the discovery of radium and polonium, would have been cause for public celebration in her adopted France, but for the nearly simultaneous revelation of her affair with fellow physicist Paul Langevin, the fellow standing to the right of a 32-year-old Albert Einstein in the above group photo from the 1911 Solvay Conference in Physics. Both stories broke while Curie—unsurprisingly, the sole woman in the photo—was attending the conference in Brussels. Equally unsurprisingly, the press preferred la scandal to la réalisation scientifique. Sex sells, then and now. The fires of radium which beam so mysteriously...have just lit a fire in the heart of one of the scientists who studies their action so devotedly; and the wife and the children of this scientist are in tears.... —Le Journal, November 4, 1911 There's no denying that the affair was painful for Langevin’s family, particularly his wife, Jeanne, who supplied the media with incriminating letters from Curie to her husband. She must have been aware that Curie would be the one to bear the brunt of the public’s disapproval. Double standards with regard to gender are nothing new. A furious throng gathered outside of Curie’s house and anti-Semitic papers, dissatisfied with labeling the pioneering scientist a mere home wrecker, declared—erroneously—that she was Jewish. The timeline was tweaked to suggest that Curie had taken up with Langevin prior to her husband’s death. Fellow radiochemist Bertram Boltwood seized the opportunity to declare that "she is exactly what I always thought she was, a detestable idiot.” In the midst of this, Einstein, who had made Curie’s acquaintance at the conference, proved himself a true friend with a “don’t let the bastards get you down” letter, written on November 23. Other than a delicate allusion to Langevin as a person with whom he felt privileged to be in contact, he refrained from mentioning the cause of her misfortune. A friendly word can go a long way in times of disgrace, and Einstein supplied his new friend with some stoutly unequivocal ones, denouncing the scandalmongers as “reptiles” feasting on sensationalistic “hogwash”: Highly esteemed Mrs. Curie, Do not laugh at me for writing you without having anything sensible to say. But I am so enraged by the base manner in which the public is presently daring to concern itself with you that I absolutely must give vent to this feeling. However, I am convinced that you consistently despise this rabble, whether it obsequiously lavishes respect on you or whether it attempts to satiate its lust for sensationalism! I am impelled to tell you how much I have come to admire your intellect, your drive, and your honesty, and that I consider myself lucky to have made your personal acquaintance in Brussels. Anyone who does not number among these reptiles is certainly happy, now as before, that we have such personages among us as you, and Langevin too, real people with whom one feels privileged to be in contact. If the rabble continues to occupy itself with you, then simply don’t read that hogwash, but rather leave it to the reptile for whom it has been fabricated. With most amicable regards to you, Langevin, and Perrin, yours very truly, A. Einstein PS I have determined the statistical law of motion of the diatomic molecule in Planck’s radiation field by means of a comical witticism, naturally under the constraint that the structure’s motion follows the laws of standard mechanics. My hope that this law is valid in reality is very small, though. That deliberately geeky postscript amounts to another sweet show of support. Perhaps it fortified Curie when a week later, she received a letter from Nobel Committee member Svante Arrhenius, urging her to skip the Prize ceremony in Stockholm. Curie rejected Arrhenius’ suggestion thusly: The prize has been awarded for the discovery of radium and polonium. I believe that there is no connection between my scientific work and the facts of private life. I cannot accept ... that the appreciation of the value of scientific work should be influenced by libel and slander concerning private life. For a more in-depth look at Marie Curie’s nightmarish November, refer to “Honor and Dishonor” the sixteenth chapter in Barbara Goldsmith’s Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie. Related Content: Albert Einstein Imposes on His First Wife a Cruel List of Marital Demands Marie Curie’s Research Papers Are Still Radioactive 100+ Years Later Marie Curie Invented Mobile X-Ray Units to Help Save Wounded Soldiers in World War I Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Read the “Don’t Let the Bastards Get You Down” Letter That Albert Einstein Sent to Marie Curie During a Time of Personal Crisis (1911) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/12/18 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |