[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, December 26th, 2017

| Time | Event |

| 6:52a | Advanced Algorithms: A Free Course from Harvard University From Harvard professor Jelani Nelson comes "Advanced Algorithms," a course intended for graduate students and advanced undergraduate students. All 25 lectures you can find on Youtube here. Here's a quick course description: "An algorithm is a well-defined procedure for carrying out some computational task. Typically the task is given, and the job of the algorithmist is to find such a procedure which is efficient, for example in terms of processing time and/or memory consumption. CS 224 is an advanced course in algorithm design, and topics we will cover include the word RAM model, data structures, amortization, online algorithms, linear programming, semidefinite programming, approximation algorithms, hashing, randomized algorithms, fast exponential time algorithms, graph algorithms, and computational geometry" "Advanced Algorithms" will be added to our collection of Free Computer Science Courses, a subset of our collection, 1,300 Free Online Courses from Top Universities. Related Content: Learn Digital Photography with Harvard University’s Free Online Course Learn to Code with Harvard’s Popular Intro to Computer Science Course: The 2016 Edition Algorithms for Big Data: A Free Course from Harvard Advanced Algorithms: A Free Course from Harvard University is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | How Fleetwood Mac Makes A Song: A Video Essay Exploring the “Sonic Paintings” on the Classic Album, Rumours Pretty much everyone with a passing familiarity with Fleetwood Mac knows at least a little something about the personal tumult behind their landmark 1977 album Rumours: it’s one of rock’s most famous soap operas,” writes Jordan Runtagh at Rolling Stone. Christine McVie put it even more succinctly— “Drama. Dra-ma.” But isn't this how great songs get written, as we find out when we read the autobiographies and interviews of great songwriters, who sublimate their personal ups and downs in lyrics that touch the emotional lives of millions? The saga of Fleetwood Mac just happens to be a particularly juicy example, given that the band members’ romantic anguish mostly came from failed relationships with each other. The tale will forever be a cautionary one for musicians, though it’s hardly much of a deterrent. Just listen to those songs! But as Evan Puschak—otherwise known as video essayist the Nerdwriter—shows above, it takes a lot more than a bad breakup with the guitar player to make timeless pop art. Rumours “feels alive, months and years and decades after its creation.” It’s so much more than the sum of its parts, even if those parts are rare and indispensable: the considerable musicianship on display, the songwriting experience, and especially the “virtually unlimited budget and time” Warner Brothers allotted the band. Such extravagance is virtually impossible for anyone else to come by. Still, noodling indefinitely with fancy instruments and equipment does not a great album make. Puschak takes Stevie Nicks’ “Dreams” as an example of how the band excelled in the studio. Written “in about 10 minutes,” as Nicks tells it, while she sat in a “big black-velvet bed with Victorian drapes” in a studio belonging to Sly Stone, the song’s studio version shows off the lush, layered production the band spent the better part of a year bringing to her two-chord demo. “Dreams”—one of the most mesmerizing songs in the band’s canon—acquired its hypnotic qualities through the use of a looped drum pattern, pulsing, repetitive bassline, and the subtle coloration of guitar textures that give the deceptively simple song its ebb and flow. The story of Rumours is as much about fantastic songcraft, musicianship, arranging, and production as it is about triumph over the human resources nightmare behind the scenes. The personal inspiration for these songs makes for good gossip, but these are not life events anyone needs to emulate to make art. Fleetwood Mac’s collective inventiveness, emotional honesty, and skill are what ultimately make them such an inspiration to musicians, and creative types in general. For another example of how they built the architectural marvels on Rumours, see the short take above from Polyphonic about the album’s moodiest song, “The Chain.” Related Content: Stevie Nicks “Shows Us How to Kick Ass in High-Heeled Boots” in a 1983 Women’s Self Defense Manual Watch Documentaries on the Making of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here Inside the Making of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band, Rock’s Great Concept Album Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Fleetwood Mac Makes A Song: A Video Essay Exploring the “Sonic Paintings” on the Classic Album, <i>Rumours</i> is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:00p | Photographer Nan Goldin Now on Instagram

A quick heads up: Back in August, Cindy Sherman, one of the best Goldin's Instagram account makes its debut at the same time that Steidl Books has re-released Nan Goldin: The Beautiful Smile--the memoir in which Goldin famously photographed, writes The New York Times, the subjects who "have been those closest to her: Transsexuals, cross-dressers, drug users, lovers, all people she befriended when she moved to New York" and who lived in what mainstream critics would coldly call the 'margins of society'." The highly-praised book is now out again. Related Content: Say What You Really Mean with Downloadable Cindy Sherman Emoticons Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Launches Free Course on Looking at Photographs as Art Photographer Nan Goldin Now on Instagram is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:30p | Why Should We Read Charles Dickens? A TED-Ed Animation Makes the Case You can’t go near the literary press lately without hearing mention of Nathan Hill’s sprawling new novel, The Nix, widely praised as a comic epic on par with David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. Novelist John Irving, to whom Hill has drawn comparisons, goes so far as to compare the novelist to Charles Dickens. Such praise goes too far, if you ask Current Affairs editor Brianna Rennix. In a caustic review essay, Rennix unfavorably measures not only The Nix, but also the postmodern novels of Wallace, Pynchon, McCarthy, Franzen, and DeLillo, against the baggy Victorian serialized works of writers like Dickens and George Eliot. “Books like Middlemarch,” she writes, “took seriously the idea that novels had the power to transform human life, not merely—as seems to be the goal of a lot of postmodern novels—to riff off its foibles for the purpose of making the author look clever.” It’s possible to appreciate Rennix’s essay as a reader of more ecumenical tastes—as someone who happens to enjoy Dickens and Eliot and all the authors she dismisses. There’s much more to the postmodern novel than she allows, but there are also very good reasons particular to our age for us turn, or return, to Dickens. In the TED-Ed video above, scripted by literary scholar Iseult Gillespie (who previously made a case for Virginia Woolf), we get some of them. For all the fun he had with human foibles, Dickens was also a social realist, the greatest influence on later literary naturalism, who “shed light on how his society’s most invisible people lived.” Unlike many novelists, in his own time and ours, Dickens had the personal experience of living in such conditions to draw on for his authentic portrayals. Nonetheless, Dickens’ did not allow his enormous popular success to blunt his compassion and concern for the plight of working people and the poor and socially marginalized. The engrossing, highly entertaining plots and characters in his novels are always pressed into service. We might call his motives political, but the term is too often pejorative. The "Dickensian" mode is a humanist one. Dickens’ did not push specific ideological agendas; he tried, as Alain de Botton says in his introductory video above, “to get us interested in some pretty serious things: the evils of an industrializing society, the working conditions in factories, child labor, vicious social snobbery, the maddening inefficiencies of government bureaucracy.” He tried, in other words, to move his readers to care about the people around them. What they chose to do with that care was, of course, then, as now, up to them. Related Content: An Animated Introduction to Charles Dickens’ Life & Literary Works Why Should We Read Virginia Woolf? A TED-Ed Animation Makes the Case Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Why Should We Read Charles Dickens? A TED-Ed Animation Makes the Case is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

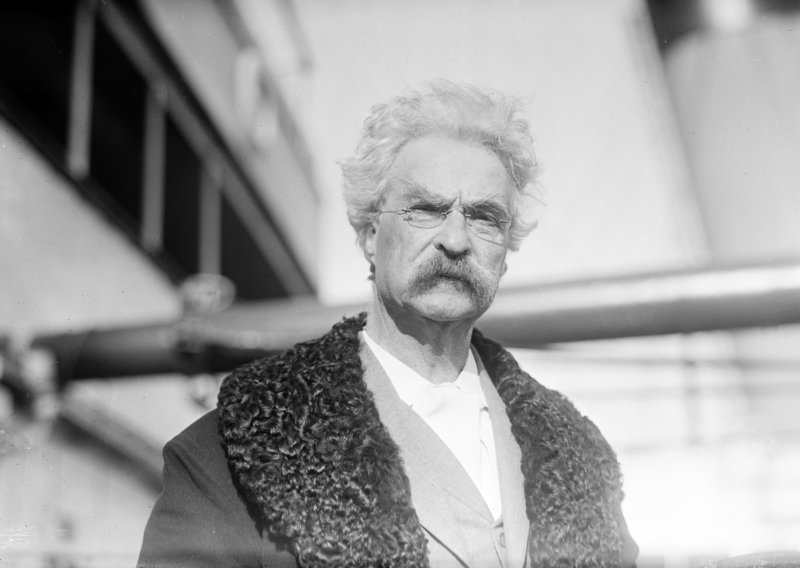

| 7:00p | Mark Twain on Why “Travel is Fatal to Prejudice, Bigotry and Narrow-Mindedness, and Many of Our People Need It Sorely on These Accounts” (1869)

Public Domain image via Wikimedia Commons Humanity has come up with many negative stereotypes of Americans, some of them not entirely groundless: the widely held belief, for example, that Americans don't get out much. I admit the truth of that one as an American myself — albeit an American who now lives in Asia — because I certainly did drag my feet on getting a passport and getting out there in the world at first. Perhaps I can take comfort in the fact that no less a colossus of American letters began his international travels even later than I did, though when he did get around to it, he got even more out of it: not only The Innocents Abroad, one of the best-loved travel books of all time, but an insight into what makes travel so vital a pursuit in the first place. The travels Mark Twain recounts in the book began in 1867 on the chartered vessel Quaker City, which took him and a group of his countrymen through Europe and the Holy Land, an itinerary including a stop at the 1867 Paris Exhibition and journeys through the Papal States to Rome and through the Black Sea to Odessa, all followable on a hypertext map at the University of Virginia's Mark Twain in His Times page. "In his account Mark Twain assumes two alternate roles," says the Library of America, "at times the no-nonsense American who refuses to automatically venerate the famous sights of the Old World (preferring Lake Tahoe to Lake Como), or at times the put-upon simpleton, a gullible victim of flatterers and 'frauds,' and an awe-struck admirer of Russian royalty." Whether you read The Innocents Abroad in the Library of America's edition or in one of a variety of free formats downloadable from Project Gutenberg, you'll eventually come to Twain's justification for the entire project: not the writing project with its handsome remuneration and name-making popularity, but the project of travel itself. Though many elements of the Old World experience, as well as prolonged exposure to his fellow Americans, put his formidable complaining ability to the test, the "breezy, shrewd, and comical manipulator of English idioms and America’s mythologies about itself and its relation to the past" (as the Library of America describes him) ultimately admits that

Distinctly Twainian words, of course, but many other writers have since also tried to express the uniquely mind-expanding properties of spending time outside your homeland. As Rudyard Kipling memorably put it to his own countrymen, a few decades after The Innocents Abroad, in "The English Flag," "What should they know of England who only England know?" Or as one writer friend of mine, well-known for the globalized nature of his books and well as of his own identity, once said, "If Americans don't travel, we're like a man who lives in a hovel assuming everyone else lives in a worse hovel." But it always comes back to Twain, who knew that "nothing so liberalizes a man and expands the kindly instincts that nature put in him as travel and contact with many kinds of people" — and who also knew that nobody quite realized "what a consummate ass he can become until he goes abroad." We can all think of much worse reasons to head across the ocean than that. Related Content: Mark Twain Makes a List of 60 American Comfort Foods He Missed While Traveling Abroad (1880) A Journey Back in Time: Vintage Travelogues Free: Read 9 Travel Books Online by Monty Python’s Michael Palin Petite Planète: Discover Chris Marker’s Influential 1950s Travel Photobook Series Join Clive James on His Classic Television Trips to Paris, LA, Tokyo, Rio, Cairo & Beyond Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Mark Twain on Why “Travel is Fatal to Prejudice, Bigotry and Narrow-Mindedness, and Many of Our People Need It Sorely on These Accounts” (1869) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2017/12/26 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |