[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, January 8th, 2018

| Time | Event |

| 6:06p | Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” Reworked in Major Key, Becomes a Cheerful Pop Song Last year, Josh Jones took a good look at what happens when Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” gets shifted from minor to major key, and Radiohead’s “Creep” moves in the opposite direction. Suddenly, two songs you know so well sound so different. Over the weekend, "Sleep Good," a psychedelic pop band from Austin, TX, took their own whack at shifting Nirvana's 1991 song into major key. And the result will catch you a bit off-guard. A grunge anthem abruptly turns into a cheery pop song, and the bopping cheerleaders in the original music video strangely fit into the mood of the adapted song. You can find a version of "Teen Sprite," as the song has been dubbed, over on Soundcloud. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content 1,000 Musicians Play Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” Live, at the Same Time Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” Reworked in Major Key, Becomes a Cheerful Pop Song is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:01p | A Supercut of Buster Keaton’s Most Amazing Stunts–and Keaton’s 5 Rules of Comic Storytelling Joseph Frank Keaton was born into showbiz. His father was a comedian. His mother, a soubrette. He emerged into the world during a one night engagement in Kansas City. His father’s business partner, escape artist Harry Houdini, inadvertently renamed him Buster, approving of the way the rubbery little Keaton weathered an accidental tumble down a flight of stairs. As Keaton recalls in the interview accompanying silent movie fan Don McHoull’s edit of some of his most amazing stunts, above: My old man was an eccentric comic and as soon as I could take care of myself at all on my feet, he had slapped shoes on me and big baggy pants. And he'd just start doing gags with me and especially kickin' me clean across the stage or taking me by the back of the neck and throwing me. By the time I got up to around seven or eight years old, we were called The Roughest Act That Was Ever in the History of the Stage. By the time of his first film role in the 1917 Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle vehicle, The Butcher Boy, Keaton was a seasoned clown, with plenty of experience stringing physical gags into an entertaining narrative whole. Like his silent peers, Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin, Keaton was an idea man, who saw no need for a script. Armed with a firm concept of how the film should begin and end, he rolled cameras without much idea of how the middle would turn out, fine tuning his physical set pieces on the fly, scrapping the ones that didn’t work and embracing the happy accidents. Could such an approach work for today’s comedians? In later interviews, Keaton was generous toward other comedy professionals who got their laughs via methods he steered clear of, from Bob Hope’s wordiness to director Billy Wilder’s deft handling of Some Like It Hot’s farcical cross-dressing. His was never a one-size-fits-all philosophy. Perhaps it's more helpful to think of his approach as an antidote to creative block and timidity. We’ve cobbled together some of his advice, below, in the hope that it might prove useful to storytellers of all stripes. Buster Keaton’s 5 Rules of Comic Storytelling Make a strong start - grab the audience with a dynamic, easy to grasp premise, like the one in 1920’s One Week, which finds a newlywed Buster struggling to assemble a house from a do-it-yourself kit. Decide how you want things to finish up - for Keaton, this usually involved getting the girl, though he learned to keep a poker face after a preview audience booed the broad grin he tried out in one of Arbuckle’s shorts. Once you know where your story’s going, trust that the middle will take care of itself. If it’s not working, cut it - Keaton may not have had a script, but he invested a lot of thought into the physical set pieces of his films. If it didn’t work as well as he hoped in execution, he cut it loose. If some serendipitous snafu turned out to be funnier than the intended gag, he put that in instead. Play it like it matters to you. As many a beginning improv student finds out, if you let your own material crack you up, the audience is rarely inclined to laugh along. Why settle for low stakes and diffidence, when high stakes and commitment are so much funnier? Action over words Whether dealing with dialogue or exposition, Keaton strove to minimize the intertitles in his silent work. Show, don’t tell. Films excerpted at top:

Related Content: Buster Keaton: The Wonderful Gags of the Founding Father of Visual Comedy Some of Buster Keaton’s Great, Death-Defying Stunts Captured in Animated Gifs The Power of Silent Movies, with The Artist Director Michel Hazanavicius Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday. A Supercut of Buster Keaton’s Most Amazing Stunts–and Keaton’s 5 Rules of Comic Storytelling is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

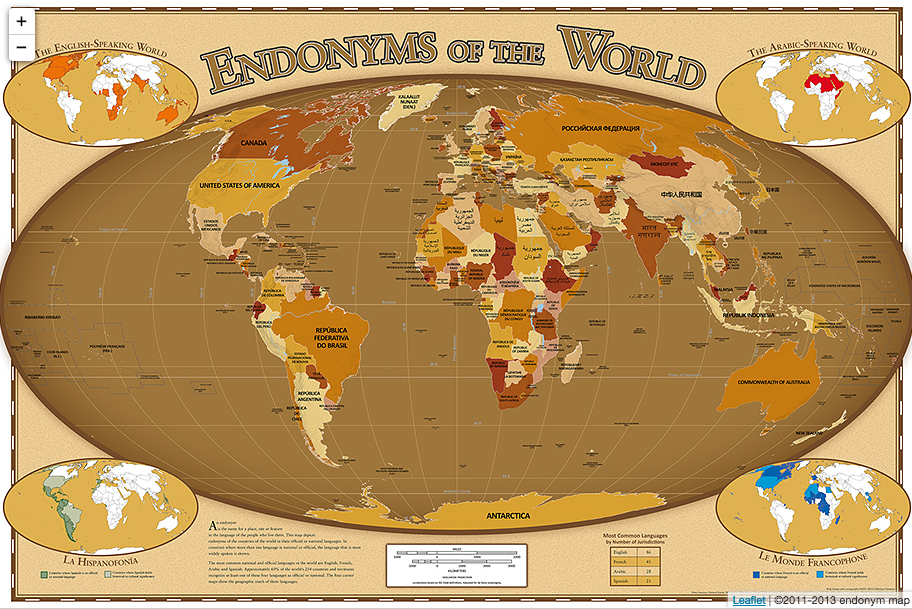

| 8:00p | A Map Shows What Every Country in the World Calls Itself in its Own Language: Explore the “Endonyms of the World” Map

I live in South Korea, but the South Koreans don't call it South Korea. The country has its own language, of course, and that language has its own name for the country, daehan minguk (대한 민국), or more commonly hanguk (한국) — not that it stops the global branding-friendly letter K, which has made its way from "K-pop" to "K-beauty" to even (albeit much less successfully) things like "K-food." As far as our much-reported-on northern neighbor, South Koreans call it bukhan (북한), but its inhabitants call their land joseon minjujueui inmin gonghwaguk (조선민주주의인민공화국). And as with Korea South and North, so with every country in the world: each one has an endonym.

"An endonym is the name for a place, site or location in the language of the people who live there. These names may be officially designated by the local government or they may simply be widely used." So says the front page of the Endonym Map, which labels every country (or disputed territory) in the world with its endonym, written in the language's own script. When you first learned the names of foreign countries, you actually learned their exonyms, their names in a foreign language: yours. "South Korea" and "North Korea" are exonyms, as are names like "Japan," "Finland," "Turkey," and "France." Nihon-koku (日本国), Suomen tasavalta, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, and la République française all appear on the Endonym Map, as do many other well-known countries you might at first glance assume you've never heard of.

The map's creator notes that "the most common official or national language in the world is English, with 86 countries or territories," which represents "one-third the number of total countries and approximately 30% of the planet's land area." Because of that, people all over the world do tend to know the English exonym for their own country, but that's hardly an excuse not to learn its real name should you decide to pay them a visit. And that counts as the first step toward actually learning its language, a journey that the Foreign Service Institute's language-learning map we featured last year can help you plan. Hwaiting, as we say here in the Koreanized English — or Englishized Korean? — of hanguk. You can view the Endonym Map in a larger, zoomable format here. Related Content: The Favorite Literary Work of Every Country Visualized on a World Map A Map Showing How Much Time It Takes to Learn Foreign Languages: From Easiest to Hardest 1934 Map Resizes the World to Show Which Country Drinks the Most Tea “Every Country in the World”–Two Videos Tell You Curious Facts About 190+ Countries Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. A Map Shows What Every Country in the World Calls Itself in its Own Language: Explore the “Endonyms of the World” Map is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 9:00p | Hear the 50 Best Post-Punk Albums of All Time: A Nostalgia-Inducing Playlist Curated by Paste Magazine Postmodernism began as an architectural term to describe the loss of a seemingly stable social order and the building of new forms in the 1960s and 70s. The new architecture was an elaborate patchwork of high and low culture and past and present design trends. In both theory and practice, postmodernism delighted in odd juxtapositions and self-referential irony. It did not shy away from politics but made sardonic critical commentary its métier rather than the totalizing agendas of late modernism. Postmodernism added to modernism's genre-hopping a broader cultural scope and wider inclusivity of forms of expression. We can see a similar cultural shift happening in popular music in the mid- to late-20th century. The pop and rock of the sixties fragmented into dozens of radio friendly genres, all of which found met their critical match in the aggressiveness of punk, a movement with high aesthetic commitments and a corresponding desire to detonate cultural norms by any means necessary. When we arrive at the "post-punk," we find all things counter-culture rubbing up against each other, filling the void left by the old social order with new sounds and visions, some determinedly grim, some playful and ironic, nearly all of them danceable. A fine description for what the world of “post-punk” looked like comes from a recent personal essay by the poet Patrick Rosal:

This was a time when bands like Public Image Limited (John Lydon’s post Sex Pistols project) and Bauhaus incorporated dub reggae rhythms, basslines, and studio effects into the core of their sound. The Clash had already embarked on such experiments, and Clash guitarist Mick Jones took things further with Big Audio Dynamite, a punk/funk/reggae/hip hop hybrid that didn’t make the list of Paste Magazine’s “50 Best Post-Punk Albums,” but was certainly representative of a strain of post-punk expansiveness. Bauhaus doesn’t make the list either, but Public Image Limited’s 1979 Metal Box appears, at number 14, an album of wobbly, dub-inflected “death disco” that won a special place in the hearts and record collections of an eclectic group of fans as the eighties dawned. At #36 we find the equally experimental Dub Housing, the 1978 second album of Ohio’s Pere Ubu, a project that coalesced in the midst of Cleveland’s punk scene to make what frontman David Thomas called “avant garage.” These disparate bands define post-punk as much as do the jangly, southern, Byrds-influenced sounds of R.E.M. or The dB’s, the surf-rock revivalism of The B52’s, jazzy, angular art-rock of Television, jittery, So-Cal punk/jazz/country/funk of Minutemen, dark drone of Joy Division, chaotic blues-punk of Birthday Party, anarchic noise and motorik beats of Swell Maps or Sonic Youth, shambling rants of The Fall, new romantic pop of The Smiths or Orange Juice, satirical synthpunk of Devo…. The list can and does go on and on. You can see the full 50 at Paste Magazine, chosen and annotated by the magazine’s writers. Above, we’ve compiled 48 of these albums in a Spotify playlist—save Metal Box and Dub Housing, which are not available on Spotify. This is music made by people “interested in seeing where music could go.” Many of them former punks, many new to the scene. Many of them left behind these early experimental phases to become more conventionally genre-based, while some had only started to push in new directions later in their career. Some of these bands arrived at a sound, made it their own, and rarely deviated, some shifted and changed throughout their career; some burned brightly, or darkly, for a short time, leaving indelible marks of odd greatness in a time when popular music took more risks than before or maybe since. At least that’s what it feels like looking back. If this is a nostalgia trip for you, you’ll find it’s pretty comprehensive, with the inevitable omission of a favorite album, band, or two (where, I must ask, is My Bloody Valentine?) If you’re new to the range of this music, consider that, for all the vagary a term like “post-punk” might evoke, like the “postmodern,” it has a specific historical context, one in which a handful of artists saw tremendous creative opportunity amidst a general sense of cultural malaise. Related Content: The History of Punk Rock in 200 Tracks: An 11-Hour Playlist Takes You From 1965 to 2016 33 Songs That Document the History of Feminist Punk (1975-2015): A Playlist Curated by Pitchfork Hear the 20 Favorite Punk Albums of Black Flag Frontman Henry Rollins Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Hear the 50 Best Post-Punk Albums of All Time: A Nostalgia-Inducing Playlist Curated by <i>Paste Magazine</i> is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2018/01/08 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |