[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, January 9th, 2018

| Time | Event |

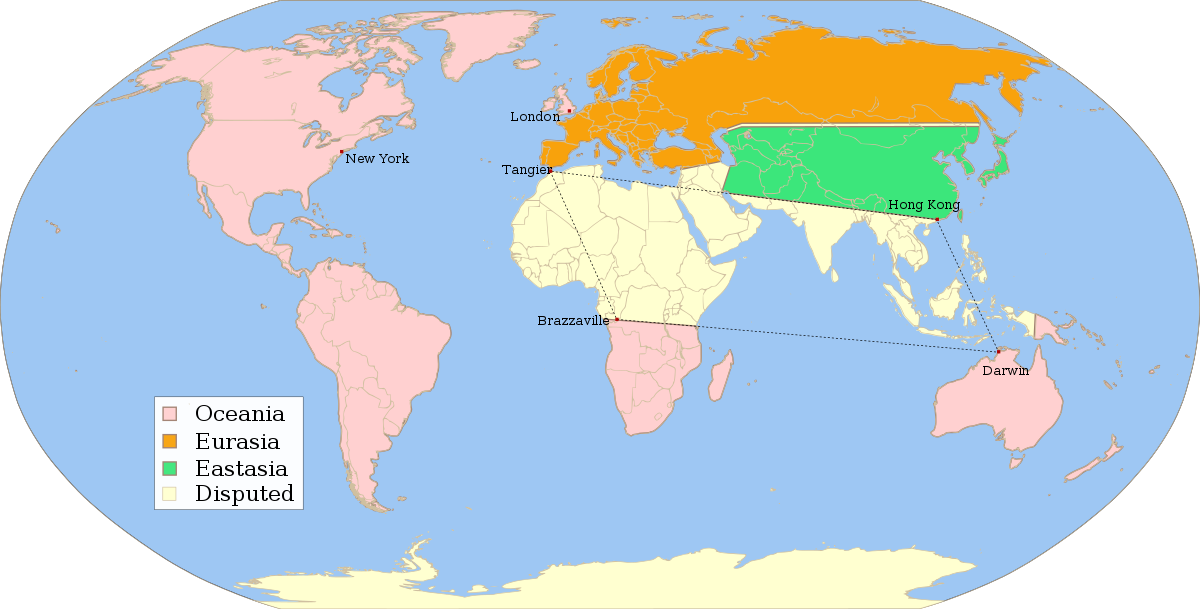

| 9:00a | A Map of George Orwell’s 1984

Many fictional locations resist mapping. Our imaginations may thrill, but our mental geolocation software recoils at the impossibilities in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities—a series of geographically whimsical tales told by Marco Polo to Genghis Khan; or China Miéville’s The City and the City, in which two metropolises—Besźel and Ul Qoma—occupy much of the same physical space, and a secretive police power compels citizens to willfully “unsee” one city or the other. That’s not to say such maps cannot be made. Calvino’s strange cities have been illustrated, if not at street level, in as fanciful a fashion as the narrator describes them. Miéville’s weird cities have received several literal-minded mapping treatments, which perhaps mistake the novel’s careful construction of metaphor for a kind of creative urban planning. Miéville himself might disavow such attempts, as he disavows one-to-one allegorical readings of his fantastic detective novel—those, for example, that reduce the phenomenon of “unseeing” to an Orwellian means of thought control. “Orwell is a much more overtly allegorical writer,” he tells Theresa DeLucci at Tor, “although it’s always sort of unstable, there’s a certain kind of mapping whereby x means y, a means b.” Orwell’s speculative worlds are easily decoded, in other words, an opinion shared by many readers of Orwell. But Miéville’s comments aside, there’s an argument to be made that The City and the City’s “unseeing” is the most vividly Orwellian device in recent fiction. And that the fictional world of 1984 does not, perhaps, yield to such simple mapping as we imagine. Of course it's easy to draw a map (see above, or in a larger format here) of the three imperial powers the novel tells us rule the world. Frank Jacobs at Big Think tidily sums them up:

These three superstates are perpetually at war with each other, though who's at war with whom is unclear. “And yet... the war might just not even be real at all”—for all we know it might be a fabrication of the Ministry of Truth, to manufacture consent for austerity, mass surveillance, forced nationalism, etc. It’s also possible that the entirety of the novel’s geo-politics have been invented out of whole cloth, that “Airstrip One is not an outpost of a greater empire," Jacobs writes, "but the sole territory under the command of Ingsoc.” One commenter on the map—which was posted to Reddit last year—points out that “there isn’t any evidence in the book that this is actually how the world is structured.” We must look at the map as doubly fictional, an illustration, Lauren Davis notes at io9, of “how the credulous inhabitant of Airstrip One, armed with only maps distributed by the Ministry of Truth, might view the world, how vast the realm of Oceania seems and how close the supposed enemies in Eurasia.” It is the world as the minds of the novel's characters conceive it. All maps, we know, are distortions, shaped by ideology, belief, perspectival bias. 1984’s limited third-person narration enacts the limited views of citizens in a totalitarian state. Such a state necessarily uses force to prevent the people from independently verifying constantly shifting, contradictory pieces of information. But the novel itself states that force is largely irrelevant. “The patrols did not matter… Only the Thought Police mattered.” In Orwell's fiction "similar outcomes" as those in totalitarian states, as Noam Chomsky remarks, "can be achieved in free societies like England" through education and mass media control. The most unsettling thing about the seeming simplicity of 1984’s map of the world is that it might look like almost anything else for all the average person knows. Its elementary-school rudiments metaphorically point to frighteningly vast areas of ignorance, and possibilities we can only imagine, since Winston Smith and his compatriots no longer have the ability, even if they had the means. Related Content: George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984 A Complete Reading of George Orwell’s 1984: Aired on Pacifica Radio, 1975 Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness A Map of George Orwell’s <i>1984</i> is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | A Short Animated Introduction to Karl Marx Is Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism still relevant to the 21st century? Can we ever read him independently of the movements that violently seized state power in his name, claiming to represent the workers through the sole will of the Party? These are questions Marxists must confront, as must all serious defenders of capitalism, who cannot afford to ignore Marx. He understood and articulated the problems of political economy better than any theorist of his day and posed a formidable intellectual challenge to the values liberal democracies claim to espouse, and those they actually practice through economic exploitation, perpetual rent-seeking, and the alienating commodification of everything. In his School of Life video explainer above, Alain de Botton sums up the received assessment of Communist history as “disastrously planned economies and nasty dictatorships.” “Nevertheless,” he says, we should view Marx “as a guide, whose diagnosis of capitalism’s ills helps us to navigate toward a more promising future”—the future of a “reformed” capitalism. No Marxist would ever make this argument; de Botton’s video appeals to the skeptic, new to Marx and not wholly inoculated against giving him a hearing. His ideas get boiled down to some mostly uncontroversial statements: Modern work is alienating and insecure. The rich get richer while wages fall. Such theses have attained the status of self-evident truisms. More interesting and provocative is Marx’s (and Engels’) notion that capitalism is “bad for capitalists,” in that it produces the repressive, patriarchal dominion of the nuclear family, “fraught with tension, oppression, and resentment.” Additionally, the imposition of economic considerations into every aspect of life renders relationships artificial and forms of life sharply constrained by the demands of the labor market. Here Marx’s economic critique takes on its subtly radical feminist dimension, de Botton says, by claiming that “men and women should have the permanent option to enjoy leisure,” not simply the equal opportunity to sell their labor power for equal amounts of insecurity. The video won’t sway staunchly anti-communist minds, but it might make some viewers curious about what exactly it was Marx had to say. Those who turn to his masterwork, Das Kapital, are likely to give up before they reach the twists and turns of the arguments de Botton outlines in broad strokes. The first and most famous volume is hard going without a guide, and you’ll find fewer better than David Harvey, Professor of Anthropology and Geography at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. Harvey’s Companion to Marx’s Capital has guided readers through the text for years, and his lectures on Marx have done so for students going on four decades. In the video above, see an introduction to Harvey’s lecture series on volume one of Marx’s Capital, and at our previous post, find complete videos of his full lecture series on Volumes One, Two, and part of Volume Three. Harvey doesn’t claim that a kinder, gentler capitalism can be found in Marx. But as to the question of whether Marx is still relevant to the vastly accelerated, technocratic capitalism of the present, he would unequivocally answer yes. Related Content: David Harvey’s Course on Marx’s Capital: Volumes 1 & 2 Now Available Free Online 6 Political Theorists Introduced in Animated “School of Life” Videos: Marx, Smith, Rawls & More What Makes Us Human?: Chomsky, Locke & Marx Introduced by New Animated Videos from the BBC Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness A Short Animated Introduction to Karl Marx is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:31p | Spheres Dance to the Music of Bach, Performed by Glenn Gould: An Animation from 1969 From Norman McLaren and René Jodoin comes a 1969 short animation called "Spheres." Here, you can watch "spheres of translucent pearl float weightlessly in the unlimited panorama of the sky, grouping, regrouping or colliding like the stylized burst of some atomic chain reaction." All the while, "the dance is set to the musical cadences of Bach, played by pianist Glenn Gould." A perfect combination. This film participates in a long tradition of animations exploring geometry, some of which you can find in the Relateds right below. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. Related Content: The First Avant Garde Animation: Watch Walter Ruttmann’s Lichtspiel Opus 1 (1921) Chuck Jones’ The Dot and the Line Celebrates Geometry & Hard Work: An Oscar-Winning Animation (1965) Journey to the Center of a Triangle: Watch the 1977 Digital Animation That Demystifies Geometry Watch “Geometry of Circles,” the Abstract Sesame Street Animation Scored by Philip Glass (1979)

Spheres Dance to the Music of Bach, Performed by Glenn Gould: An Animation from 1969 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00p | Watch Gyorgy Ligeti’s Electronic Masterpiece Artikulation Get Brought to Life by Rainer Wehinger’s Brilliant Visual Score Even if you don't know the name György Ligeti, you probably already associate his music with a set of mesmerizing visions. The work of that Hungarian composer of 20th-century classical music appealed mightily to Stanley Kubrick, so much so that he used four of Ligeti's pieces to score 2001: A Space Odyssey. One of them, 1962's Aventures, plays over the final scenes in an electronically altered form, which drew a lawsuit from the composer who'd been unaware of the modification. But he didn't do it out of purism: though he wrote, over his long career, almost entirely for traditional instruments, he'd made a couple forays into electronic music himself a decade earlier. Ligeti fled Hungary for Vienna in 1956, soon afterward making his way to Cologne, where he met the electronically innovative likes of Karlheinz Stockhausen and Gottfried Michael Koenig and worked in West German Radio's Studio for Electronic Music. There he produced 1957's Glissandi and 1958's Artikulation, the latter of which lasts just under four minutes, but, in the words of The Guardian's Tom Service, "packs a lot of drama in its diminutive electronic frame." Ligeti himself "imagined the sounds of Artikulation conjuring up images and ideas of labyrinths, texts, dialogues, insects, catastrophes, transformations, disappearances," which you can see visualized in shape and color in the "listening score" in the video above. Created in 1970 by graphic designer Rainer Wehinger of the State University of Music and Performing Arts Stuttgart, and approved by Ligeti himself, the score's "visuals are beautiful to watch in tandem with Ligeti's music; there's an especially arresting sonic and visual pile-up, about 3 mins 15 secs into the piece. This isn't electronic music as postwar utopia, a la Stockhausen, it's electronics as human, humorous drama," writes Service. Have a watch and a listen, or a couple of them, and you'll get a feel for how Wehinger's visual choices reflect the nature of Ligeti's sounds. Just as 2001 still launches sci-fi buffs into an experience like nothing else in the genre, those sounds will still strike a fair few self-described electronic music fans of the 21st century as strange and new — especially when they can see them at the same time. Related Content: Watch What Happens When 100 Metronomes Perform György Ligeti’s Controversial Poème Symphonique The Genius of J.S. Bach’s “Crab Canon” Visualized on a Möbius Strip The Classical Music in Stanley Kubrick’s Films: Listen to a Free, 4 Hour Playlist Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Watch Gyorgy Ligeti’s Electronic Masterpiece <i>Artikulation</i> Get Brought to Life by Rainer Wehinger’s Brilliant Visual Score is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2018/01/09 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |