[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, January 11th, 2018

| Time | Event |

| 7:00a | The “True” Story Of How Brian Eno Invented Ambient Music

Or maybe it didn't actually happen that way... To learn more about Eno's Oblique Strategies, see our archived post: Jump Start Your Creative Process with Brian Eno’s “Oblique Strategies” Deck of Cards (1975). Related Content: Charles Schulz Draws Charlie Brown in 45 Seconds and Exorcises His Demons Umberto Eco Explains the Poetic Power of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts The “True” Story Of How Brian Eno Invented Ambient Music is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 9:00a | Watch the History of the World Unfold on an Animated Map: From 200,000 BCE to Today "Where are you from?" a character at one point asks Babe, the hapless protagonist of the Firesign Theatre's classic comedy album How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You're Not Anywhere at All. "Nairobi, ma'am," Babe replies. "Isn't everybody?" Like most of that psychedelic radio troupe's pieces of apparent nonsense, that memorable line contains a truth: trace human history back far enough and you inevitably end up in east Africa, a point illustrated in reverse by the video above, "A History of the World: Every Year," which traces the march of humanity between 200,000 BCE and the modern day. To a dramatic soundtrack which opens and closes with the music of Hans Zimmer, video creator Ollie Bye charts mankind's progress out of Africa and, ultimately, into every corner of all the continents of the world. Real, documented settlements, cities, empires, and entire civilizations rise and fall as they would in a computer game, with a constantly updated global population count and list of the civilizations active in the current year as well as occasional notes about politics and diplomacy, society and culture, and inventions and discoveries. All that happens in under 20 minutes, a pretty swift clip, though not until the very end does the world take the political shape we know today, including even the late latecomer to civilization that is the United States of America. Bye's many other videos tend to focus on the history of other parts of the world, such as India, the British Isles, and that cradle of our species, the African continent, all of which we can now develop first-hand familiarity with in this age of unprecedented human mobility. Though the condition itself takes the question "Where are you from?" to a degree of complication unknown not only millennia but also centuries and even decades ago, at least now you have a snappy answer at the ready. Related Content: The History of Civilization Mapped in 13 Minutes: 5000 BC to 2014 AD Take Big History: A Free Short Course on 13.8 Billion Years of History, Funded by Bill Gates The History of the World in 46 Lectures From Columbia University The History of the World in 20 Odd Minutes A Crash Course in World History 5-Minute Animation Maps 2,600 Years of Western Cultural History Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Watch the History of the World Unfold on an Animated Map: From 200,000 BCE to Today is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

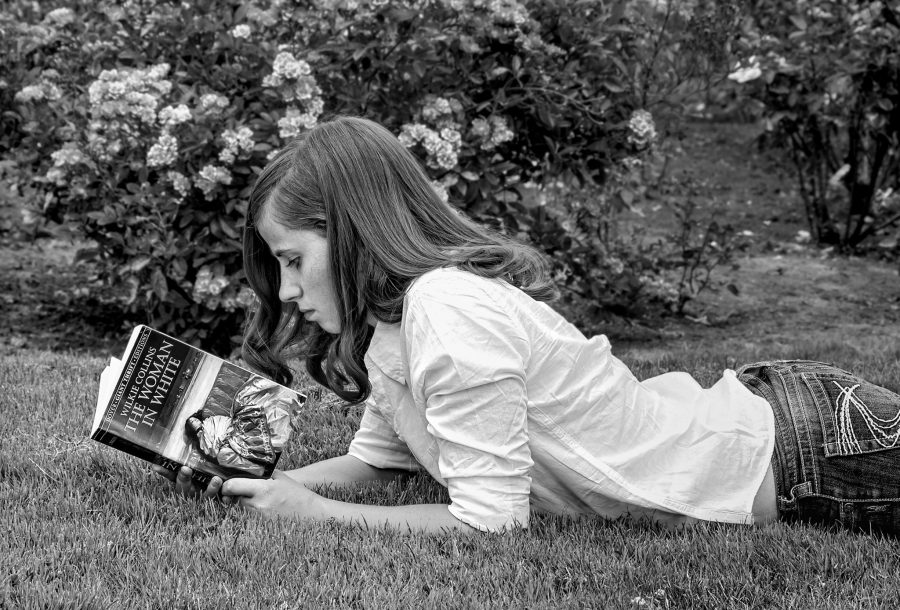

| 12:00p | How Reading Increases Your Emotional Intelligence & Brain Function: The Findings of Recent Scientific Studies

Image by Sheila Sund, via Flickr Commons Reading “availeth much,” to borrow an old phrase from the King James Bible. To read is to experience more of the world than we can in person, to enter into the lives of others, to organize knowledge according to useful schemes and categories…. Or, at least it can be. Much recent research strongly suggests that reading improves emotional and cognitive intelligence, by changing and activating areas of the brain responsible for these qualities. Is reading essential for the survival of the species? Perhaps not. “Humans have been reading and writing for only about 5000 years—too short for major evolutionary changes,” writes Greg Miller in Science. We got by well enough for tens of thousands of years before written language. But neuroscientists theorize that reading “rewires” areas of the brain responsible for both vision and spoken language. Even adults who learn to read late in life can experience these effects, increasing "functional connectivity with the visual cortex," some researchers have found, which may be "the brain's way of filtering and fine-tuning the flood of visual information that calls for our attention" in the modern world. This improved communication between areas of the brain might also represent an important intervention into developmental disorders. One Carnegie Mellon study, for example, found that "100 hours of intensive reading instruction improved children's reading skills and also increased the quality of... compromised white matter to normal levels." The findings, says Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, suggest "an exciting approach to be tested in the treatment of mental disorders, which increasingly appear to be due to problems in specific brain circuits." Reading can not only improve cognition, but it can also lead to a refined “theory of mind,” a term used by cognitive scientists to describe how "we ascribe mental states to other persons"—as the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes—and "how we use the states to explain and predict the actions of those other persons." Improved theory of mind, or "intuitive psychology," as it's also called, can result in greater levels of empathy and perhaps even expanded executive function, allowing us to better "hold multiple perspectives in mind at once," writes Brittany Thompson, "and switch between those perspectives." Improved theory of mind comes primarily from reading narratives, research suggests. One meta-analysis published by Raymond A. Mar of Toronto’s York University reviews many of the studies demonstrating the effect of story comprehension on theory of mind, and concludes that the better we understand the events in a narrative, the better we are able to understand the actions and intentions of those around us. The kinds of narratives we read, moreover, might also make a difference. One study, conducted by psychologists David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano of the New School for Social Research, tested the effect of differences in writing quality on empathy responses, randomly assigning 1,000 participants excerpts from both popular bestsellers and literary fiction. To define the difference between the two, the researchers referred to critic Roland Barthes' The Pleasure of the Text. As Kidd explains:

The researchers used two theory of mind tests to measure degrees of empathy and found that “scores were consistently higher for those who had read literary fiction than for those with popular fiction or non-fiction texts,” notes Liz Bury at The Guardian. Other research has found that descriptive language stimulates regions of our brains not classically associated with reading. “Words like ‘lavender,’ ‘cinnamon’ and ‘soap,’ for example,” writes Annie Murphy Paul at The New York Times, citing a 2006 study published in NeuroImage, “elicit a response not only from the language-processing areas of our brains, but also those devoted to dealing with smells.” Reading, in other words, can effectively simulate reality in the brain and produce authentic emotional responses: “The brain, it seems, does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life”—that is, if the experience is written about in sensory language. The emotional brain also does not seem to make a tremendous distinction between reading the written word and hearing it recited or read. When study participants in a joint German and Norwegian experiment, for example, heard poetry read aloud, they experienced physical sensations and “about 40 percent showed visible goose bumps.” But different kinds of texts elicit different kinds of responses. We can read or listen to a novel, for example, and, instead of only experiencing sensations, can “live several lives while reading,” as William Styron once wrote. The authors of a 2013 Emory University study published in Brain Connectivity conclude that reading novels can rewire areas of the brain, causing “transient changes in functional connectivity.” These biological changes were found to last up to five days after study participants read Robert Harris' 2003 novel Pompeii. The heightened connectivity in certain regions "corresponded to regions previously associated with perspective taking and story comprehension." So what? asks a skeptical Ian Steadman at New Statesman. Reading may create changes in the brain, but so does everything else, a phenomenon well-known by now as “neuroplasticity.” Much of the reporting on the neuroscience of reading, Steadman argues, overinterprets the research to support an “[x] ‘rewires’ the brain” myth both common and “mistaken.” Steadman’s critiques of the Brain Connectivity study are perhaps well-placed. The small sample size, lack of a control group, and neglect of questions about different kinds of writing make its already tentative conclusions even less impressive. However, more substantive research, taken together, does show that the “rewiring” that happens when we read—though perhaps temporary and in need of frequent refreshing—really does make us more cognitively and socially adept. And that the kind of reading—or even listening—that we do really does matter. via BigThink/The Guardian/Harvard Related Content: This Is Your Brain on Jane Austen: The Neuroscience of Reading Great Literature 900 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free 7 Tips for Reading More Books in a Year Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Reading Increases Your Emotional Intelligence & Brain Function: The Findings of Recent Scientific Studies is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | A Brief History of Making Deals with the Devil: Niccolò Paganini, Robert Johnson, Jimmy Page & More When the term “witch hunt” gets thrown around in cases of powerful men accused of harassment and abuse, historians everywhere bang their heads against their desks. The history of persecuting witches—as every schoolboy and girl knows from the famous Salem Trials—involves accusations moving decidedly in the other direction. But we’re very familiar with men supposedly selling out to Satan, dealing—or just dueling—with the devil. They weren’t called witches for doing so, or burned at the stake. They were blues pioneers, virtuoso fiddlers, and guitar gods. From the devilishly dashing Niccolò Paganini, to Robert Johnson at the Crossroads, to Jimmy Page's black magic, to “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” to the omnipresence of Satan in metal…. The devil “seems to have quite the interest in music,” notes the Polyphonic video above. Before musicians came to terms with the dark lord, power-hungry scholars used demonology to summon Luciferian emissaries like Mephistopheles. The legend of Faust dates back to the late 16th century and a historical alchemist named Johann Georg Faust, who inspired many dramatic works, like Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, Johann Goethe’s Faust, Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, Mikhail Bugakov’s The Master and Margarita, and F.W. Murnau’s 1926 silent film. The Faust legend may be the sturdiest of such stories, but it is not by any means the origin of the idea. Medieval Catholic saints feared the devil's enticements constantly. Medieval occultists often saw things differently. If we can trace the notion of women consorting with the devil to the Biblical Eve in the Garden, we find male analogues in the New Testament—Christ's temptations in the desert, Judas's thirty pieces of silver, the possessed vagrant who sends his demons into a herd of pigs. But we might even say that God made the first deal with the devil, in the opening wager of the book of Job. In most examples—Charlie Daniels' triumphal folk tale aside—the deal usually goes down badly for the mortal party involved, as it did for Robert Johnson when the devil came for his due, and convened the morbidly fascinating 27 Club. Goethe imposes a redemptive happy ending onto Faust that seems to wildly overcompensate for the typical fate of souls in hell’s pawn shop. Kierkegaard took the idea seriously as a cultural myth, and wrote in Either/Or that “every notable historical era will have its own Faust.” Modern-day Fausts in the popular genre of the day, the conspiracy theory, are famous entertainers, as you can see in the unintentionally humorous supercut above from a YouTube channel called “EndTimeChristian.” As it happens in these kinds of narratives, the cultural trope gets taken far too literally as a real event. The Faust legend shows us that making deals with the devil has been a literary device for hundreds of years, passing into popular culture, then the blues—a genre haunted by hell hounds and infernal crossroads—and its progeny in rock and roll and hip hop. Those who talk of selling their souls might really believe it, but they inherited the language from centuries of Western cultural and religious tradition. Selling one’s soul is a common metaphor for living a carnal life, or getting into bed with shady characters for worldly success. But it’s also a playful notion. (A misunderstood aspect of so much metal is its comic Satanic overkill.) Johnson himself turned the story of selling his soul into an iconic boast, in “Crossroads” and “Me and the Devil Blues.” “Hello Satan,” he says in the latter tune, “I believe it’s time to go.” Chilling in hindsight, the line is the bluesman’s grimly casual acknowledgment of how life on the edge would catch up to him. But it was worth it, he also suggests, to become a legend in his own time. In the short, animated video above from Music Matters, Johnson meets the horned one, a slick operator in a suit: “Suddenly, no one could touch him.” Often when we talk these days about people selling their souls, they might eventually end up singing, but they don’t make beautiful music. In any case, the moral of almost every version of the story is perfectly clear: no matter how good the deal seems, the devil never fails to collect on a debt. Related Content: The Story of Bluesman Robert Johnson’s Famous Deal With the Devil Retold in Three Animations Watch Häxan, the Classic Cinematic Study of Witchcraft Narrated by William S. Burroughs (1922) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness A Brief History of Making Deals with the Devil: Niccolò Paganini, Robert Johnson, Jimmy Page & More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

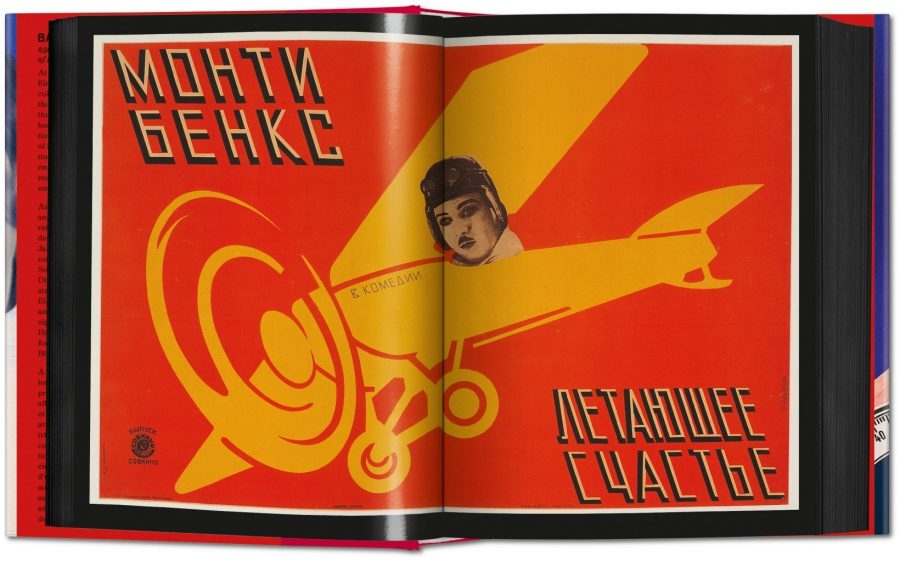

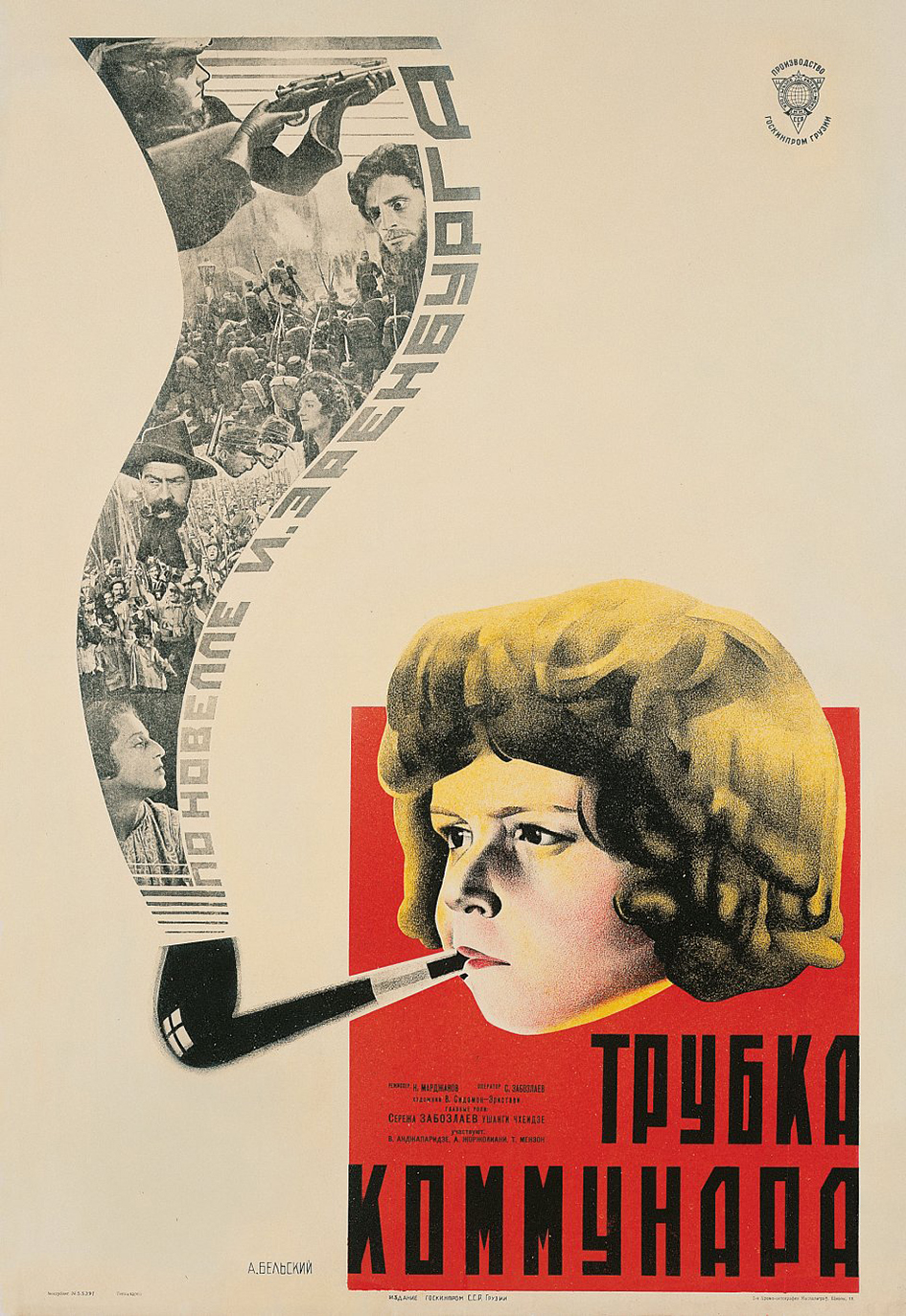

| 6:00p | The Film Posters of the Russian Avant-Garde

To commemorate the centennial of Russia’s October Revolution (it seems like only yesterday, comrade!) Taschen has yet again delivered an impressive tome of a book, entitled Film Posters of the Russian Avant-Garde. Collector Susan Pack has put together this selection of 250 posters by 27 artists for films both well known and lost to history. The book first came out in 1995, but this new edition is smaller and multilingual, like many of their new releases. The style still impresses and influences today, with its combination of photo-realist faces and the jagged energy of constructivism.

Many of the artists never saw the films they were advertising, but plainly not a bad thing here. Artists like Aleksandr Rodchenko (who was also a designer and photographer) and the Stenberg Brothers (sculptors and set designers) mixed photos with lithographs, incorporated the film’s credits into the actual art, and worried not about selling the story beyond a basic excitement level. This was art designed to get people in the door, regardless of the film. And, if you think about it, it’s art that could not exist in this current era. Who would commission a film poster blindly? Nobody, my friend.

Still, it was in no way ideal for the artists. They often had less than a day to finish something, and the printing presses were pre-revolution vintage and in various stages of repair. And very few, we can assume, thought their posters would be saved and collected. Pack’s collection often contains the only surviving copies of a certain work.

Stalin stopped all this once he took power and insisted that only socialist realism be depicted in art. This style has its own collectors, for sure, but there’s always a tinge of kitsch to it all, because it reveals the lie that was the Stalin era. Whereas the dynamism of these early posters still maintain their aesthetic hold, springing from a time where hope, excitement, and revolution were pulsing through the country and its populace. via Vice/Hyperallergic Related Content: Striking French, Russian & Polish Posters for the Films of Andrei Tarkovsky Download 144 Beautiful Books of Russian Futurism: Mayakovsky, Malevich, Khlebnikov & More (1910-30) Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW's Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here. The Film Posters of the Russian Avant-Garde is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2018/01/11 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |