[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, January 9th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | Classic Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories by Gustave Doré, Édouard Manet, Harry Clarke, Aubrey Beardsley & Arthur Rackham

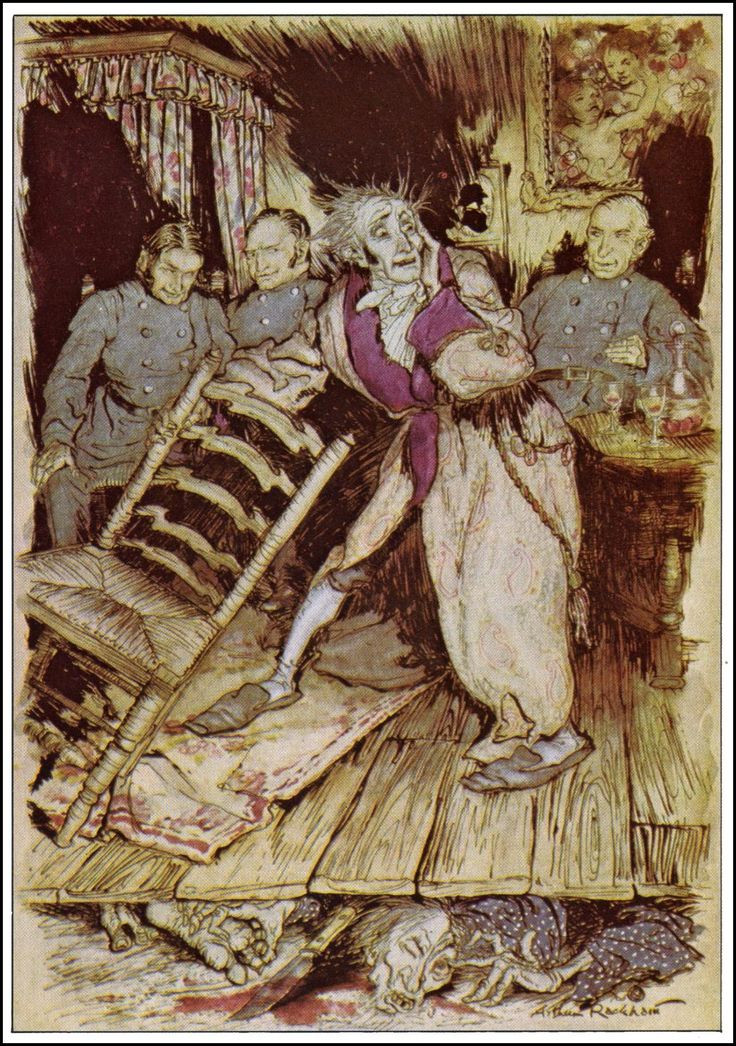

What do you see when you read the work of Edgar Allan Poe? The great age of the illustrated book is far behind us. Aside from cover designs, most modern editions of Poe’s work circulate in text-only form. That’s just fine, of course. Readers should be trusted to use their imaginations, and who can forget indelible descriptions like “The Tell-Tale Heart”’s “eye of a vulture—a pale, blue eye, with a film over it”? We need no picture book to make that image come alive. Yet, when we first discover the many illustrated editions of Poe published in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we might wonder how we ever did without them. A copy of Tales of Mystery and Imagination illustrated by Arthur Rackham in 1935 (above) served as my first introduction to this rich body of work. Known also for his editions of Peter Pan, The Wind in the Willows, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and Alice in Wonderland, Rackham’s “signature watercolor technique” was “always in high demand,” Sadie Stein writes at The Paris Review.

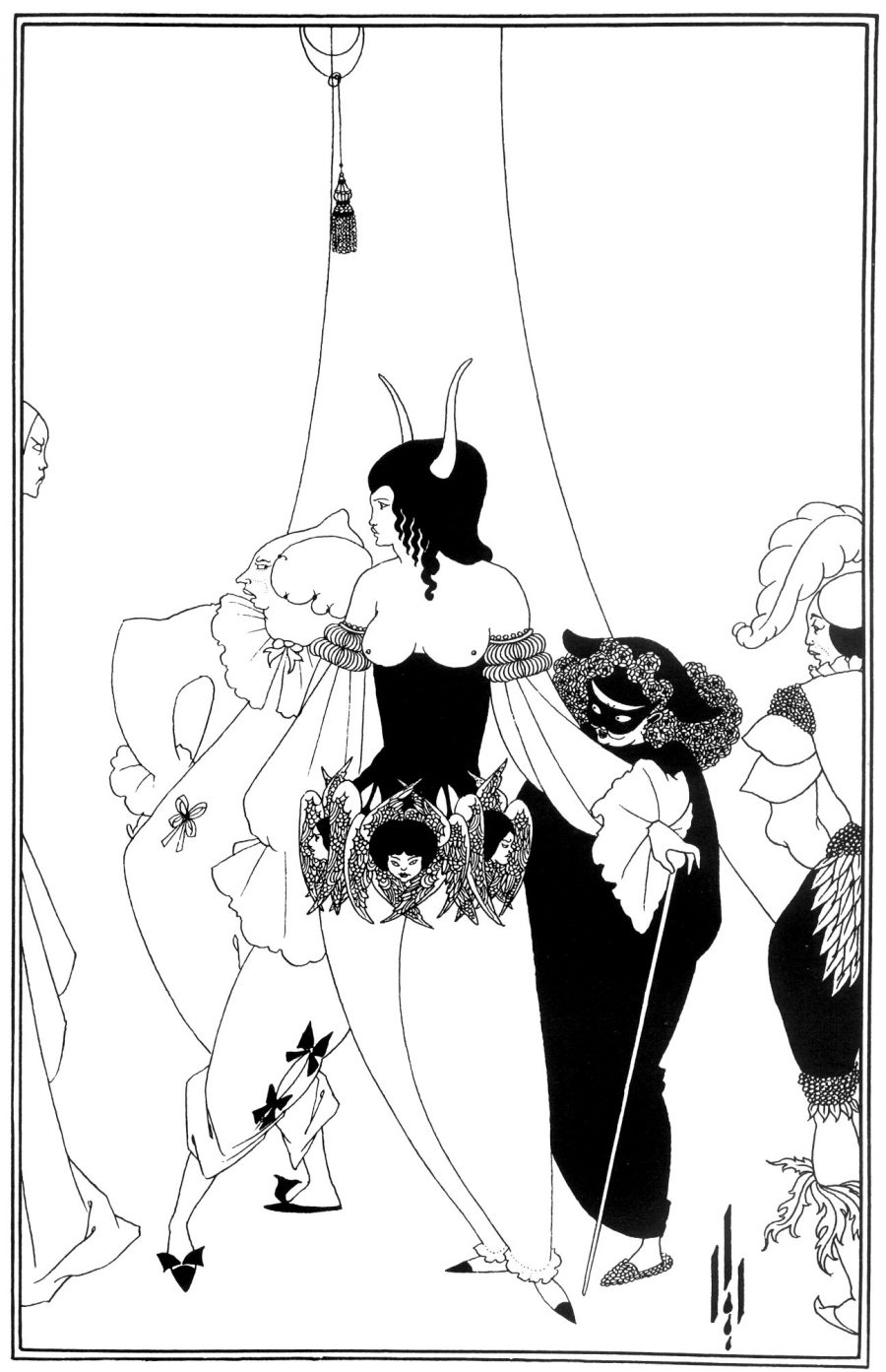

Sometime later, I came across the 1894 Symbolist illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley, and for a while, when Poe came to mind so too did Beardsley’s sensually creepy prints, influenced by Japanese woodcuts and Art Nouveau posters. His stylized take on Poe, notes Print magazine, offers “a very different aesthetic from the works of his predecessors.” Most prominent among those earlier illustrators was the hugely prolific Gustave Doré, whose classical renderings of the Divine Comedy and Don Quixote may have few equals in a field crowded with illustrated editions of those books.

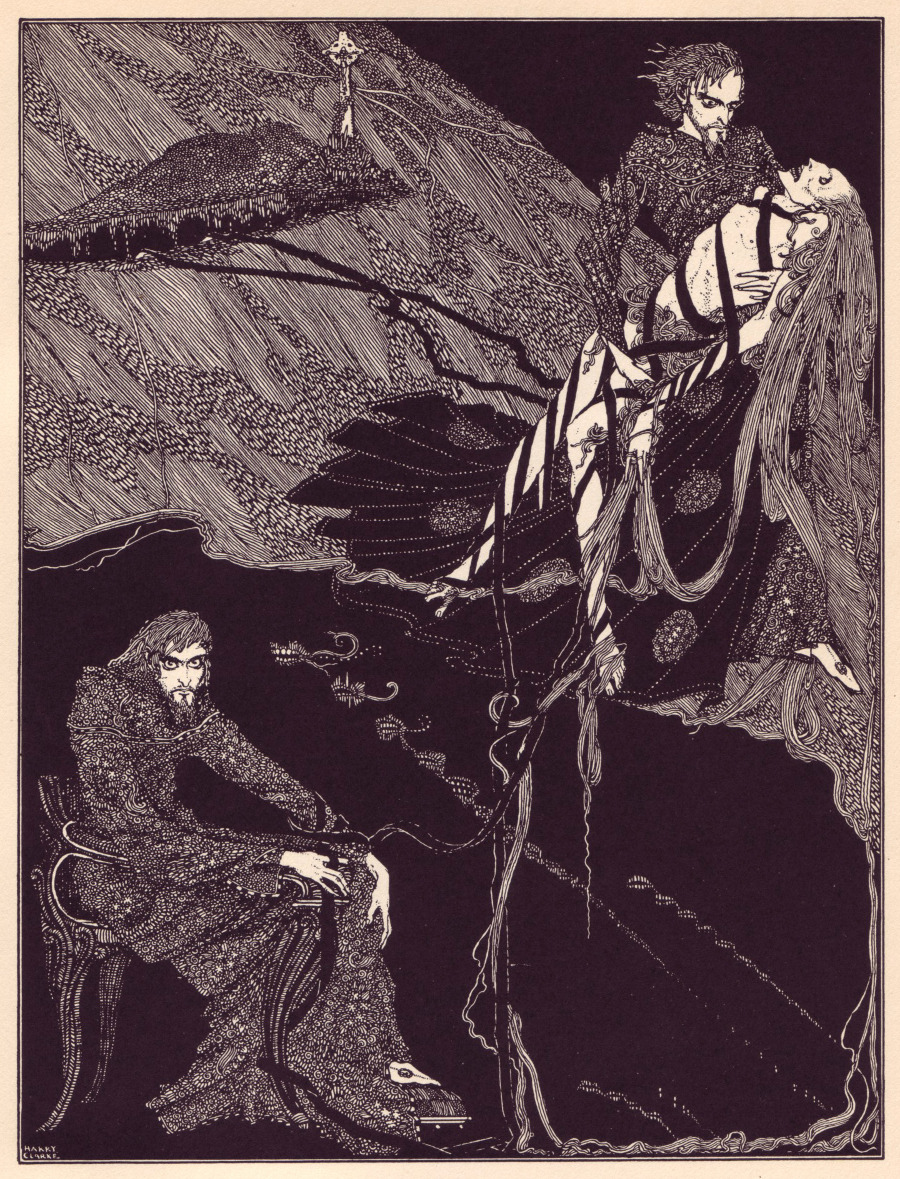

But for me, there’s something lacking, in the 26 steel engravings Doré made for an 1884 edition of Poe’s “The Raven.” They are, like all of his work, classically accomplished works of art. But unlike Beardsley, Doré seems to miss the strain of absurdism and dark humor that runs through all of Poe’s work (or at least the way I’ve read him), though it's true that "The Raven" relies on atmosphere and suggestion for its effect, rather than torture, murder, and plague. In the later, 1923 edition of Tales of Mystery and Imagination illustrated by Irish artist Harry Clarke, we find the best qualities of Beardsley and Doré combined: finely-detailed, fully-realized scenes, suffused with gothic sensuality, symbolism, grotesque weirdness, and an almost comically exaggerated sense of dread.

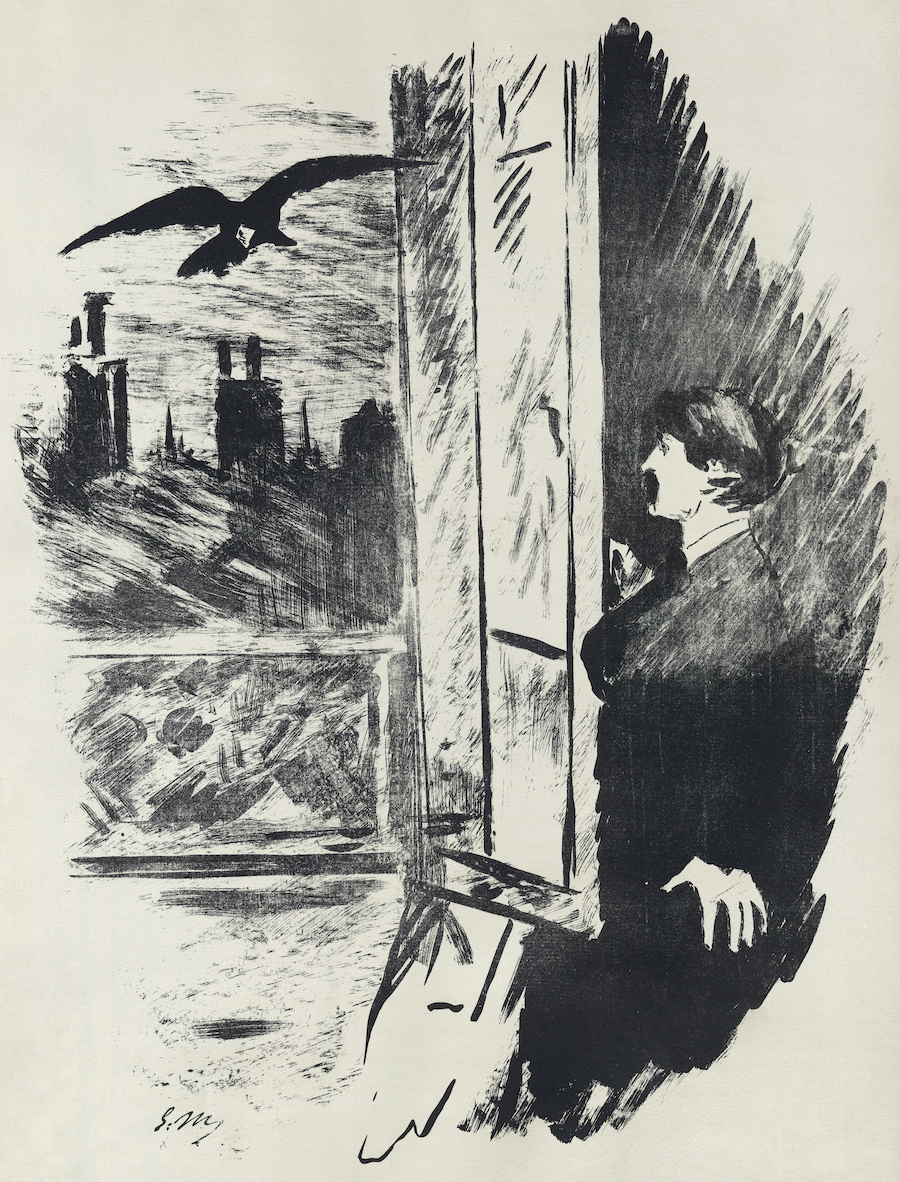

Poe significantly influenced the poetry of Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé, and Clarke foregrounds in his work many of the qualities those poets did—the tangling up of sex and death in images that attract and repulse at the same time. Early Impressionist master Édouard Manet also illustrated an 1875 edition of “The Raven," translated into French by Mallarmé. Manet draws the French poet/translator as the speaker of the poem (recognizable by his pushbroom mustache).

Manet’s minimal drawings of the poem contrast starkly with Doré’s elaborate engravings. Just as readers might imagine Poe's macabre stories in innumerable ways, so too the artists who have illustrated his work. See contemporary illustrations for “The Tell-Tale Heart,” for example, by South African artist Pencilheart Art and Brooklyn-based illustrator Daniel Horowitz, and recommend your favorite Poe artist in the comments below. Related Content: Harry Clarke’s Hallucinatory Illustrations for Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories (1923) Aubrey Beardsley’s Macabre Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s Short Stories (1894) Gustave Doré’s Splendid Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Classic Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories by Gustave Doré, Édouard Manet, Harry Clarke, Aubrey Beardsley & Arthur Rackham is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 12:00p | When Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire Were Accused of Stealing the Mona Lisa (1911)

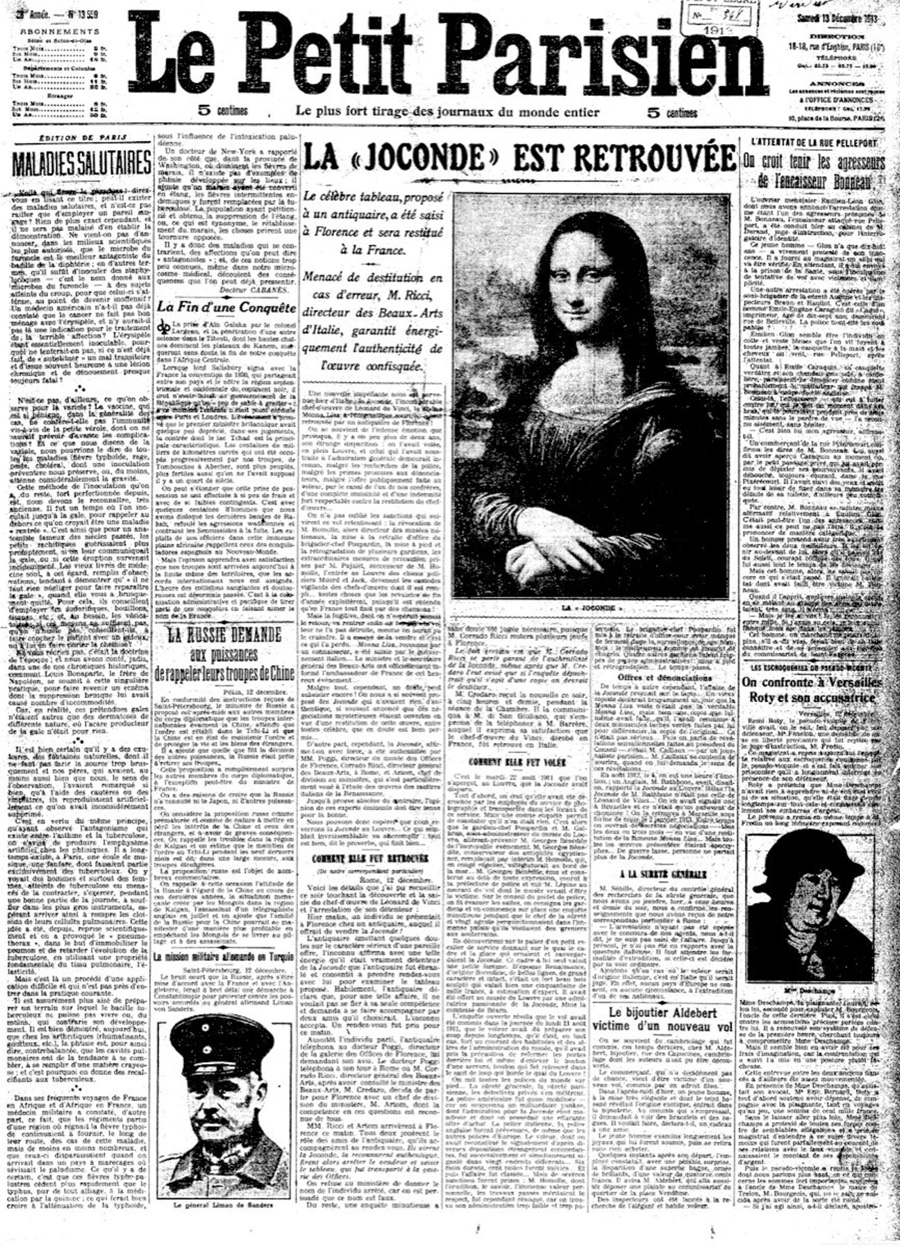

If you visit the Louvre today, you'll notice two phenomena in particular: the omnipresence of security, and the throng of visitors obscuring the Mona Lisa. If you'd visited just over a century ago, neither would have been the case. And if you happened to visit on August 22nd, 1911, you wouldn't have encountered Leonardo's famed portrait at all. That morning, writes Messy Nessy, "Parisian artist Louis Béroud, famous for painting and selling his copies of famous artworks, walked into the Louvre to begin a copy of the Mona Lisa. When he arrived into the Salon Carré where the Da Vinci had been on display for the past five years, he found four iron pegs and no painting." Béroud "theatrically alerted the sleepy guards who fumbled around for several hours under the assumption the painting might have been borrowed for cleaning or photographing, until it was finally confirmed the Mona Lisa had been stolen." The immediate measures taken: "The Louvre was closed for an entire week, museum administrators lost their jobs, the French borders were closed as every ship and train was searched and a reward of 25,000 francs was announced for the painting."

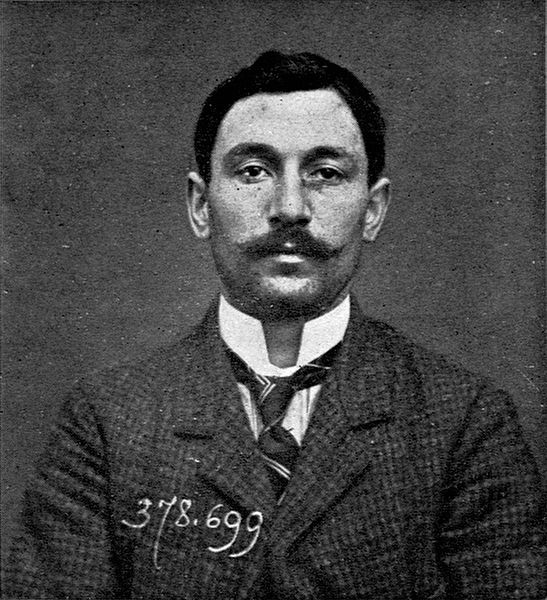

High on the list of suspects, thanks to the word of an art thief not involved in the heist named Joseph Géry Pieret: none other than Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire. Confessing to his habit of purloining small items from the Louvre, which then took no great pains to protect the cultural assets within its walls, Pieret informed the police that he had sold a couple of small Iberian statues to a "painter-friend." Pieret, writes Artsy's Ian Shank, "had left a clue — a nom de plume in one of his published confessions, pulled straight from the writings of avant-garde poet Apollinaire. (As police would later discover, Pieret was in fact the writer’s former secretary.)" As the powers that be knew, "Apollinaire was a devout member of Picasso’s modernist entourage la bande de Picasso — a group of artistic firebrands also known around town as the 'Wild Men of Paris.' Here, police believed, was a ring of art thieves sophisticated enough to swipe the Mona Lisa." Though the Spanish-born painter and Italian-born poet had nothing to do with the theft of the Mona Lisa, Picasso had indeed bought those stolen sculptures from Pieret, and in a panic nearly threw them into the Seine.

"Apollinaire confessed to everything," writes Shank, while Picasso "wept openly in court, hysterically alleging at one point that he had never even met Apollinaire. Deluged with contradictory and nonsensical testimony the presiding Judge Henri Drioux threw out the case, ultimately dismissing both men with little more than a stern admonition." Two years later, the identity of the real Mona Lisa thief came to light: a Louvre employee named Vincenzo Peruggia (shown right above), who had easily smuggled the canvas out and kept it in a trunk until such time — so he insisted — as he could repatriate the masterpiece to its, and his, homeland. All this makes for an entertaining chapter in the history of art crime, but if you still believe that Picasso must have had a hand in the Mona Lisa's disappearance, have a look at "All the Evidence That Picasso Actually Stole the Mona Lisa." Compiled by the Huffington Post's Sara Boboltz, the list includes such facts as "He was living in France at the time," "He’d technically purchased stolen artworks before" — those little Iberian sculptures — and "He loved art, duh." None could deny that last point, just as none could deny the Mona Lisa's enduring status as something of a Holy Grail for art thieves. But what modern-day Peruggia — or Picasso, or Apollinaire, or as some theories hold, Béroud — would dare make an attempt on it now? via Mental Floss/Artsy/Messy Nessy Related Content: The Adoration of the Mona Lisa Begins with Theft Mona Lisa Selfie: A Montage of Social Media Photos Taken at the Louvre and Put on Instagram Original Portrait of the Mona Lisa Found Beneath the Paint Layers of da Vinci’s Masterpiece The Postcards That Picasso Illustrated and Sent to Jean Cocteau, Apollinaire & Gertrude Stein Take a Virtual Reality Tour of the World’s Stolen Art Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. When Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire Were Accused of Stealing the Mona Lisa (1911) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | Actress Lucy Lawless Performs the Proto-Feminist Comedy “Lysistrata” for The Partially Examined Life Podcast

She has now joined the gang for cold-read on-air performances with discussions of Sartre's No Exit, Sophocles's Antigone, and most recently Aristophanes's still-funny proto-feminist comedy Lysistrata. For the discussion of this last, she was joined by fellow cast member Emily Perkins (she played the little girl on the 1990 TV version of Stephen King's "IT") to hash through whether this story of stopping war through a sex-strike is actually feminist or not, and how it relates to modern politics. (For another take on this, see Spike Lee's 2015 adaptation of the story for the film Chi-Raq.) And as a present to bring you into the New Year, she provided lead vocals on a new song by PEL host Mark Linsenmayer about the funky ways women can be put on a pedestal, projected upon, unloaded upon, and otherwise not treated as quite human despite the intention to provide affection. Stream it right below. And read the lyrics and get more information on bandcamp.com.

Related Content: Pablo Picasso’s Tender Illustrations For Aristophanes’ Lysistrata (1934) Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit: A BBC Adaptation Starring Harold Pinter (1964) Actress Lucy Lawless Performs the Proto-Feminist Comedy “Lysistrata” for The Partially Examined Life Podcast is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:22p | The Hu, a New Breakthrough Band from Mongolia, Plays Heavy Metal with Traditional Folk Instruments and Throat Singing Maybe you’re jaded, maybe you think it’s time for heavy metal to finally hang up its spikes, maybe you think there’s nowhere else for the world’s most theatrically angry music to go but maybe bluegrass…. Or maybe Mongolia, where folk metal band The Hu have been inventing what they call “Hunnu Rock,” a style combining Western headbanging with instruments like the horsehead fiddle (morin khuur) and Mongolian guitar (tovshuur). “It also involves singing in a guttural way,” Katya Cengel points out at NPR—no, not like this, but in the manner of traditional Mongolian throat singers. Now YouTube sensations with millions of views of its two videos for “Yuve Yuve Yu” and “Wolf Totem,” the band plans to release its first album this spring, after seven years of hard work. The Hu are not flash-in-the-pan internet fame seekers but serious musicians who didn’t quite expect this degree of attention, or so they say. “When we do this,” said guitarist Temka, “we try to spiritually express this beautiful thing about Mongolian music. We think we will talk to everyone’s soul through our music. But we didn’t expect this fast, people just popping up everywhere.” University of Wisconsin Kip Hutchins, a doctoral student in cultural anthropology, has taken an interest in the band and thinks their appeal, writes Cengel, has to do with how “the story of Mongolia has been written in the West. Nomadism and horse culture has been romanticized, and the emphasis on freedom and heroes tends to appeal to the stereotypical male heavy metal fan.” The band’s themes focus on past national triumphs, the legendary rule of Genghis Khan, and the glorification of the nomadic warrior’s life. Or so it would seem to Westerners parsing their lyrics in English. It may also be hard to read “Hey you traitor! Kneel down!” in a song about “taking our Great Mongol ancestors names in vain” and not think about metal’s role in a few violent ultra-nationalist scenes. Some suggest the songs are ironic or translate differently to Mongolian listeners. Or that the band might be a sophisticated satire, like Laibach, using nationalist themes, costumes, and dramatic settings on the steppes to critique nationalist narratives. One observer who knows the culture suggests it's more complicated. The Hu are not mocking traditional Mongolian culture and history, far from it. “The graphic visuals used in the video certainly evoke pride in our nomadic culture,” writes Batshandas Altansukh, “but the lyric is quite the contrary. It’s very political and highly critical of today’s Mongolian society” and what the band sees as their country’s propensity for “emptily boasting about the past” rather than actually learning about and respecting it (with motorcycle gangs riding across the plains). The lyrics we read in translation are apparently "too westernized or simplified” to really get their point across and slogans like “taking our great Mongol ancestors names in vain,” Cengel points out, “are almost exactly what was sung in the late 1980s during the transition to democracy”—a means of fiercely asserting an independent cultural identity against the hegemonic Soviet Union. Mongolian folk rock and jazz bands picked up the sentiment and Mongolian hip hop acts promote respect for the country’s traditions with new dance moves. But whether or not The Hu’s politics get wrongly interpreted, or ignored, by their millions of new fans, it’s clear that people get it at the universal level of metal’s communal frequencies: long hair, leather, guitars, growling, and epic medieval badassery. via NPR Related Content: The Origins of the Death Growl in Metal Music Finnish Musicians Play Bluegrass Versions of AC/DC, Iron Maiden & Ronnie James Dio Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Hu, a New Breakthrough Band from Mongolia, Plays Heavy Metal with Traditional Folk Instruments and Throat Singing is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/01/09 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |