[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, January 10th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | The Art of Creating Special Effects in Silent Movies: Ingenuity Before the Age of CGI If anyone tries to claim that modern day movies have too many special effects remind them of this. Films have always used special effects to trick the audience, and we’re just using new variations of tools from a century ago. In fact, right from the beginning, creators like Georges Méliès were pushing the boundaries of celluloid and 24 frames per second like the showmen and magicians they were. By the time we get to the silent comedians as seen in our above video, technology had advanced along with the pure physical comedy of the stars. Yes, they were amazing and nimble athletes, but they weren’t stupid. Camera trickery helped them look superhuman. The first example shows Harold Lloyd’s iconic stunt from 1923's Safety Last!, where he hung over the streets of Los Angeles from a clock face. Only he wasn’t really. Using forced perspective, a constructed building edifice, and a safe mattress a few feet below shows how Lloyd faced no danger at all. Editing, too, creates so much of the effect, as we have seen how high the clock is compared to the ground in previous shots. The angle on the streets below and in the distance really sell the scene compared to just shooting sky. In fact, this forced perspective is still used in modern films: Peter Jackson used it a lot in The Lord of the Rings to give the impression that Gandalf was twice as tall as Hobbit Frodo simply by constructing the sets smaller. And when backgrounds are basic like sand dunes, even the low budget filmmaker can achieve some amazing effects with no money, just a bunch of cool miniatures: Then again, Jackie Chan one-upped Lloyd for real in his 1983 film Project A, when he dangles from a three-story clock hand only to crash through two canopies onto the ground below. It’s a stunt so nice, they show you it twice! The other favorite trick of the silent films was matte painting. As long as the camera doesn’t move, a piece of glass with a photo-realistic painting on it can seamlessly fit into the action. In Charlie Chaplin’s 1936 Modern Times, that allows the comedian to skate very close to a three floor drop without even being in danger. (Technically, the camera *does* move in this shot, but it’s a short pan which wouldn’t affect the illusion.) This old-school method has gone away, though up through the ‘80s great matte painting artists were working on films like the Star Wars trilogy and Raiders of the Lost Ark. Now a digital matte artist works in three dimensions, not two, with endless finesse and tweaking at their disposal, like in Game of Thrones:

The matte is the basis, really, of all modern digital effects. Wherever there is a green screen, you’re seeing the evolution of the matte. You probably have an app on your phone that does something similar, and can magically transport you to where you really want to be...just like film. Related Content: A Supercut of Buster Keaton’s Most Amazing Stunts–and Keaton’s 5 Rules of Comic Storytelling Some of Buster Keaton’s Great, Death-Defying Stunts Captured in Animated Gifs Captivating GIFs Reveal the Magical Special Effects in Classic Silent Films Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW's Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here. The Art of Creating Special Effects in Silent Movies: Ingenuity Before the Age of CGI is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

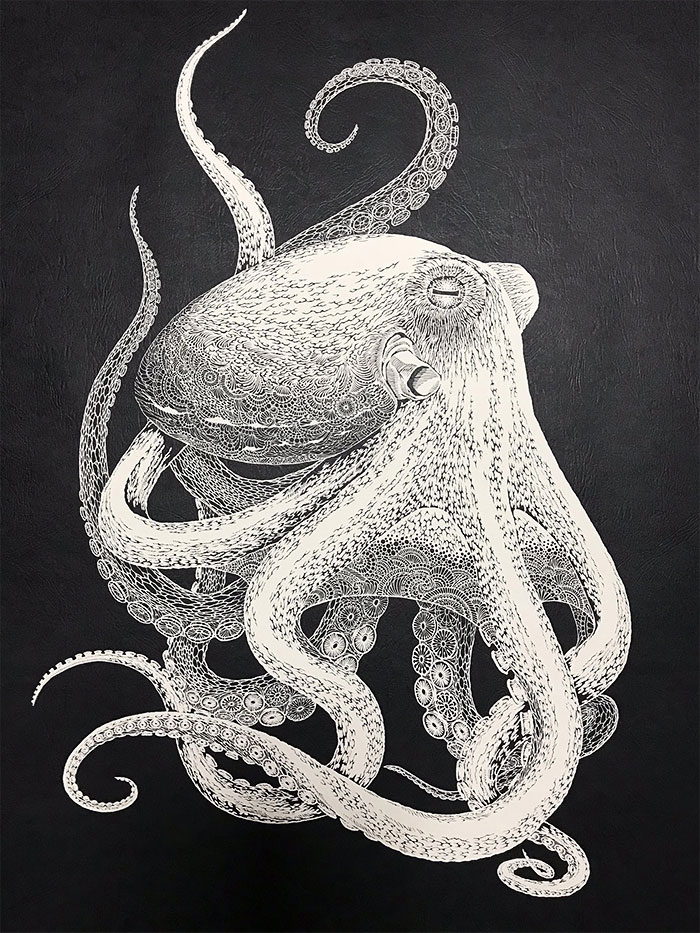

| 3:00p | Artist Hand-Cuts an Intricate Octopus From a Single Piece of Paper: Discover the Japanese Art of Kirie At first glance, the octopus in the video above might appear to be breathing. A second look reveals that it isn't actually breathing, nor is it actually an octopus at all, but seemingly just a highly detailed drawing of one. Only upon the third look, if even then, does it become clear that the octopus has been not drawn but intricately cut, and out of a single large sheet of paper at that. The two-dimensional sea creature represents a recent high point in the work of Japanese artist Masayo Fukuda, who has practiced this curious craft, known as kirie, for more than a quarter of a century now. "Kirie (???, literally ‘cut picture’) is the Japanese art of paper-cutting," writes Spoon & Tamago's Johnny Waldman. "Variations of kirie can be found in cultures around the world but the Japanese version is said to be derived from religious ceremonies and can be traced back to around the AD 700s. In its most conventional form, negative space is cut from a single sheet of white paper and then contrasted against a black background to reveal a rendering." Such painstaking work, and the astonishingly impressive artistic results that can come out of it, fit right in with the image of Japanese art and craftsmanship as the world now appreciates it. Bored Panda quotes Fukuda as saying that "cutting pictures has become a way of dissipating all the stress of my daily life.”

If you, too, would like to seek the benefits of a regular kirie practice, you don't need much in the way of equipment: "All the basics you need are TANT paper" — a brand of paper made especially for origami and other paper crafts — "a cutter, matte, and a good light source." Of course, if you look only to the work of an experienced master like Fukuda (which will go on display, Waldman notes, this April at Osaka's Miraie Gallery) for examples, you're likely to get frustrated very quickly indeed. You might consider first getting a broader overview of kirie as currently practiced, starting with this five-minute documentary showcasing the work of other paper-cutting enthusiasts in Japan. Set aside enough time for it, and approach your sheet of paper with enough patience every day, and — who knows? — one day your octopus, too, may breathe. via Spoon & Tamago Related Content: The Making of Japanese Handmade Paper: A Short Film Documents an 800-Year-Old Tradition Watch a Japanese Craftsman Lovingly Bring a Tattered Old Book Back to Near Mint Condition 20 Mesmerizing Videos of Japanese Artisans Creating Traditional Handicrafts Watch Japanese Woodworking Masters Create Elegant & Elaborate Geometric Patterns with Wood Designer Creates Origami Cardboard Tents to Shelter the Homeless from the Winter Cold MIT Creates Amazing Self-Folding Origami Robots & Leaping Cheetah Robots Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Artist Hand-Cuts an Intricate Octopus From a Single Piece of Paper: Discover the Japanese Art of Kirie is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:00p | Bertrand Russell’s 10 Commandments for Living in a Healthy Democracy

Image by J. F. Horrabin, via Wikimedia Commons Bertrand Russell saw the history of civilization as being shaped by an unfortunate oscillation between two opposing evils: tyranny and anarchy, each of which contain the seed of the other. The best course for steering clear of either one, Russell maintained, is liberalism. "The doctrine of liberalism is an attempt to escape from this endless oscillation," writes Russell in A History of Western Philosophy. "The essence of liberalism is an attempt to secure a social order not based on irrational dogma [a feature of tyranny], and insuring stability [which anarchy undermines] without involving more restraints than are necessary for the preservation of the community." In 1951 Russell published an article in The New York Times Magazine, "The Best Answer to Fanaticism--Liberalism," with the subtitle: "Its calm search for truth, viewed as dangerous in many places, remains the hope of humanity." In the article, Russell writes that "Liberalism is not so much a creed as a disposition. It is, indeed, opposed to creeds." He continues: But the liberal attitude does not say that you should oppose authority. It says only that you should be free to oppose authority, which is quite a different thing. The essence of the liberal outlook in the intellectual sphere is a belief that unbiased discussion is a useful thing and that men should be free to question anything if they can support their questioning by solid arguments. The opposite view, which is maintained by those who cannot be called liberals, is that the truth is already known, and that to question it is necessarily subversive. Russell criticizes the radical who would advocate change at any cost. Echoing the philosopher John Locke, who had a profound influence on the authors of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, Russell writes: The teacher who urges doctrines subversive to existing authority does not, if he is a liberal, advocate the establishment of a new authority even more tyrannical than the old. He advocates certain limits to the exercise of authority, and he wishes these limits to be observed not only when the authority would support a creed with which he disagrees but also when it would support one with which he is in complete agreement. I am, for my part, a believer in democracy, but I do not like a regime which makes belief in democracy compulsory. Russell concludes the New York Times piece by offering a "new decalogue" with advice on how to live one's life in the spirit of liberalism. "The Ten Commandments that, as a teacher, I should wish to promulgate, might be set forth as follows," he says: 1: Do not feel absolutely certain of anything. 2: Do not think it worthwhile to produce belief by concealing evidence, for the evidence is sure to come to light. 3: Never try to discourage thinking, for you are sure to succeed. 4: When you meet with opposition, even if it should be from your husband or your children, endeavor to overcome it by argument and not by authority, for a victory dependent upon authority is unreal and illusory. 5: Have no respect for the authority of others, for there are always contrary authorities to be found. 6: Do not use power to suppress opinions you think pernicious, for if you do the opinions will suppress you. 7: Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric. 8: Find more pleasure in intelligent dissent than in passive agreement, for, if you value intelligence as you should, the former implies a deeper agreement than the latter. 9: Be scrupulously truthful, even when truth is inconvenient, for it is more inconvenient when you try to conceal it. 10. Do not feel envious of the happiness of those who live in a fool's paradise, for only a fool will think that it is happiness. Wise words then. Wise words now. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in March, 2013. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. via Brain Pickings Related Content: Bertrand Russell: The Everyday Benefit of Philosophy Is That It Helps You Live with Uncertainty Bertrand Russell Authority and the Individual (1948) Bertrand Russell’s 10 Commandments for Living in a Healthy Democracy is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00p | The Getty Digital Archive Expands to 135,000 Free Images: Download High Resolution Scans of Paintings, Sculptures, Photographs & Much Much More

J. Paul Getty was not a billionaire known for his generosity. But since his death, the Getty Trust and complex of Getty museums in L.A. have carried forth in a more magnanimous spirit, ostensibly adhering to values that transcend their founder: “service, philanthropy, teaching, and access.” A collection first gathered for private investment and consumption (sometimes under a cloud of scandal) has expanded into galleries that millions pass through every year; a Conservation Institute dedicated to preserving the world’s art; and a Research Institute proclaiming a social mission: a devotion to expanding “our knowledge of the history of art, of all countries, of all languages,” according to its director Thomas Gaehtgens, who also says, “a society without art cannot really survive.” Put another way, as one of the Getty’s art market competitors was once quoted as saying, “They just want people to like them.” He didn’t mean it as a compliment, but if you are an art lover—and not a billionaire art collector—you may genuinely appreciate this quality. And you may like them even more now that their open access digital collections have almost doubled to 135,000 high-resolution images since we last checked in with them five years ago.

Like the Getty museum, it reflects its founder's tastes in Classical, Neo-Classical, and Renaissance art. Download Andrea Mantegna’s Adoration of the Magi (top), for example, at the highest resolution (8557 X 6559) and get closer to a virtual version than you ever could to the real thing. Learn the painting’s provenance and exhibition history, read an informative description and a bibliography. The painting is one of hundreds from European masters and their lesser-known apprentices. You’ll also find several hundred images of sculpture, both classical and modern—like Paul Gaugin’s sandalwood Head with Horns, above—as well as drawings, manuscripts, pottery, jewelry, coins, decorative arts, and much more.

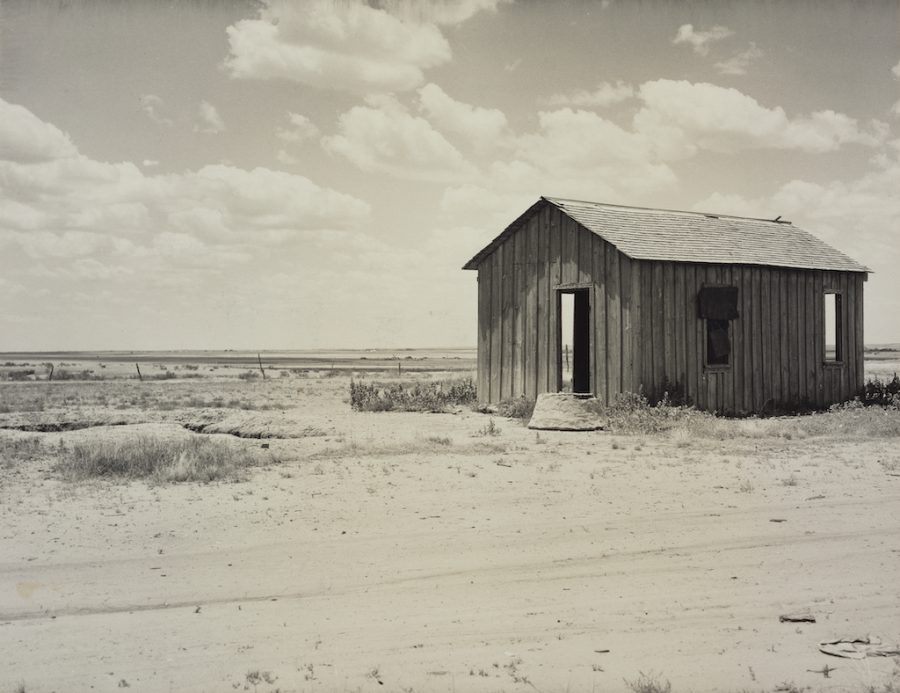

But the bulk of the digital collection consists of photographs, with 112,261 images and counting in the archive. The Getty has “assembled the finest and most comprehensive corpus of photographs on the West Coast” in its photography collection (not to be confused with Getty’s son’s media empire), with “substantial holdings by some of the most significant masters of the 20th century.” The collection is also “particularly rich in works dating from the time of photography’s invention” and its development in the mid-19th century. Download and study Dorothea Lange’s desolate Abandoned Dust Bowl Home. Or journey back to the early days of the medium, when gentleman amateurs like Scottish nobleman Ronald Ruthven Leslie-Melville took up photography as an avid pursuit, and documented the landscapes, architecture, and personages of their age. (See Ruthven-Melville’s 1860's photograph Roehampton below.)

Like all digital collections, the Getty’s cannot replicate the experience of seeing physical works of art in person, but it does magnanimously expand access to thousands of images usually hidden from the public, as well as thousands of pieces currently on display in one of its many museums. Completely free, the online archive serves as an invaluable teaching and learning tool, a vast repository preserving international art history online. Related Content: Visit a New Digital Archive of 2.2 Million Images from the First Hundred Years of Photography 1.8 Million Free Works of Art from World-Class Museums: A Meta List of Great Art Available Online Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Getty Digital Archive Expands to 135,000 Free Images: Download High Resolution Scans of Paintings, Sculptures, Photographs & Much Much More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/01/10 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |