[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, January 24th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | Watch Dziga Vertov’s A Man with a Movie Camera, the 8th Best Film Ever Made

Of all the cinematic trailblazers to emerge during the early years of the Soviet Union – Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin, Lev Kuleshov – Dziga Vertov (né Denis Arkadievitch Kaufman, 1896–1954) was the most radical. Whereas Eisenstein – as seen in that film school standard Battleship Potemkin – used montage editing to create new ways of telling a story, Vertov dispensed with story altogether. He loathed fiction films. “The film drama is the Opium of the people,” he wrote. “Down with Bourgeois fairy-tale scenarios…long live life as it is!” He called for the creation of a new kind of cinema free of the counter-revolutionary baggage of Western movies. A cinema that captured real life. At the beginning of his masterpiece, A Man with a Movie Camera (1929) – which was named in 2012 by Sight and Sound magazine as the 8th best movie ever made – Vertov announced exactly what that kind of cinema would look like:

Gleefully using jump cuts, superimpositions, split screens and every other trick in a filmmaker’s arsenal, Vertov, along with his editor (and wife) Elizaveta Svilova, crafts a dizzying, impressionistic, propulsive portrait of the newly industrializing Soviet Union. The lengths to which Vertov goes to capture this “cinematic communication of real events” is startling: His camera soars over cities and gazes up at streetcars; it films machines chugging away and even records a woman giving birth. “I am eye. I am a mechanical eye,” Vertov once famously wrote. “I, a machine, am showing you a world, the likes of which only I can see.” Yet Vertov’s stroke of genius was to expose the entire artifice of filmmaking within the movie itself. In A Man with a Movie Camera, Vertov shoots footage of his cameramen shooting footage. There’s a reoccurring shot of an eye staring through a lens. We see images from earlier in the movie getting edited into the film. This sort of cinematic self-reflexivity was decades ahead of its time, influencing such future experimental filmmakers as Chris Marker, Stan Brakhage and especially Jean-Luc Godard who in 1968 formed a radical filmmaking collective called The Dziga Vertov Group. A Man with a Movie Camera, especially with Alloy Orchestra’s accompaniment, is nothing short of exhilarating. Check it out above. Also find the classic on our list of Great Silent Films, part of our larger collection, 1,150 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc.. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in November 2014. Related Content: Eight Free Films by Dziga Vertov, Creator of Soviet Avant-Garde Documentaries 101 Free Silent Films: The Great Classics Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. Watch Dziga Vertov’s A Man with a Movie Camera, the 8th Best Film Ever Made is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 12:00p | Moebius Draws Adventurous Ads for Maxwell House Coffee (1989)

What do you do after you’ve helped create one of the “first anti-heroes in Western comics”; pioneered the underground comics industry and heavy metal album covers; won the enduring admiration of Federico Fellini, Stan Lee, and Hayao Miyazaki; and brought your distinctive creative style to the look of sci-fi classics like Blade Runner, Alien, Tron, and The Abyss? Sit back, have a coffee, and design a series of ads for Maxwell House. Why not? You’re Moebius. You can draw whatever you want. No one’s going to accuse Alejandro Jodorowsky’s partner in the legendary never-made Dune film and The Incal comics of selling out—not when contemporary comic art, science fiction, and fantasy could hardly have existed without him.

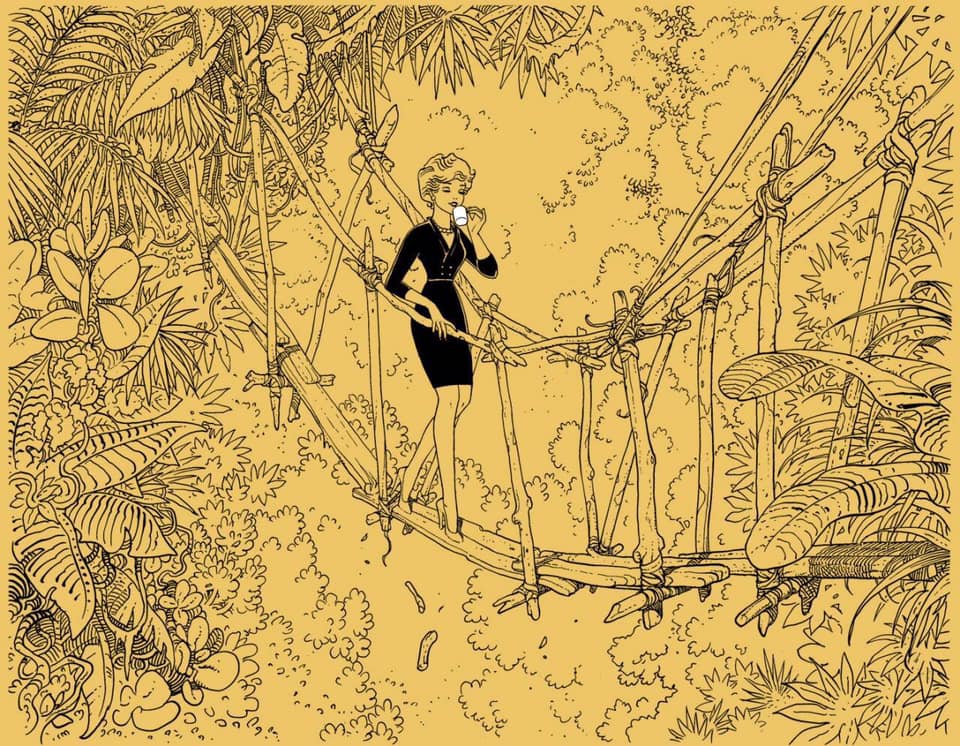

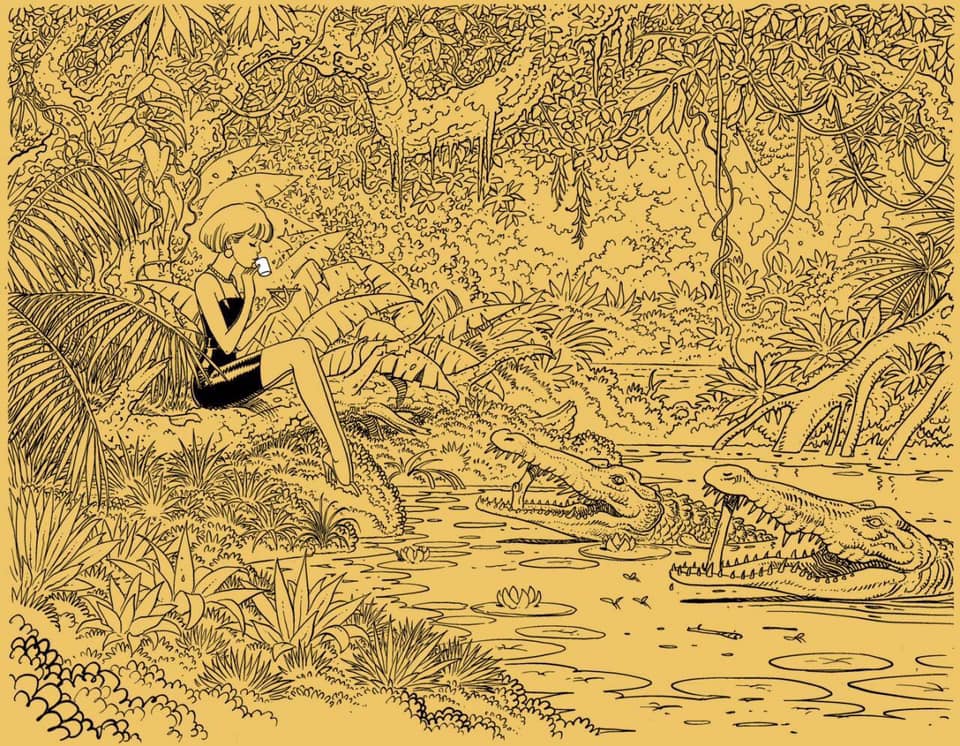

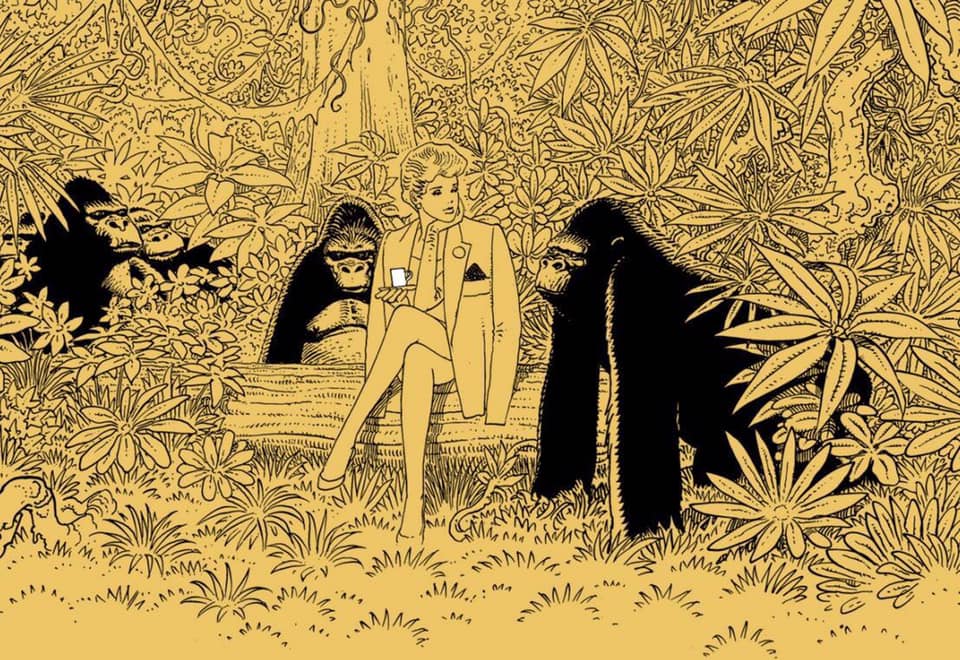

“Probably the most important fantasy comic artist of all time,” as Art Futura dubs him, the man originally known by his birth name Jean Giraud began his career as an illustrator for the youth press Fleurus, who were the first in France to publish fellow bande dessinées artist Herge’s Adventures of Tintin. The Maxwell House ads here, drawn in 1989, recall those early days of Franco-Belgian comic art, when adventurers raced around the colonies, braving wild animals and surly natives. Moebius’ confident hand leaves a signature in the dense patterns of the foliage and slender jawline of the elegant, coffee-sipping damsel, who does not seem remotely in distress, downed plane and curious gorillas notwithstanding. But the settings are just as reminiscent of Tintin’s juvenile conceptions of the Amazon and "darkest Africa," though Moebius leaves out the swashbucklers and ugly native caricatures.

Giraud’s own travels took him through Mexico—where he joined his mother as a teenager and saw for the first time the magnificent Western landscapes he had always dreamed of—and through Algeria, where he worked as an illustrator for the French army magazine while finishing his military service. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he portrayed non-European nations and people with sympathy and respect. Though he first took the name Moebius in 1974 in order to pursue more fantasy-oriented work after drawing the Western Blueberry for over a decade, some of Giraud's ‘70s comic stories under the name drew upon real events, like the murder of a North African immigrant, Wounded Knee, and the famous speech of Chief Seattle.

The Maxwell House panels keep things light and sweet, so to speak, though where the cream and sugar might be hiding is anyone’s guess. The heroine of the series, named Tatiana, is “a self-possessed and fashionable young woman who happens to find herself alone on a desert jungle island or the like,” as Martin Schneider writes at Dangerous Minds. Unperturbed, she takes more interest in her coffee than the wildness around her. At Dangerous Minds you’ll find alternate unused images and the ad campaign’s droll captions describing Tatiana taking coffee breaks from some mundane errand or chore. The commentary, though amusing, is hardly necessary. We can imagine dozens of stories embedded in each panel. The ability to create such complex and evocative illustrations, every one a world within a world, has always set Moebius ahead of his peers and many imitators. Related Content: Watch Groundbreaking Comic Artist Mœbius Draw His Characters in Real Time Mœbius & Jodorowsky’s Sci-Fi Masterpiece, The Incal, Brought to Life in a Tantalizing Animation Behold Moebius’ Many Psychedelic Illustrations of Jimi Hendrix Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Moebius Draws Adventurous Ads for Maxwell House Coffee (1989) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | Watch 110 Lectures by Donald Knuth, “the Yoda of Silicon Valley,” on Programming, Mathematical Writing, and More Many see the realms of literature and computers as not just completely separate, but growing more distant from one another all the time. Donald Knuth, one of the most respected figures of all the most deeply computer-savvy in Silicon Valley, sees it differently. His claims to fame include The Art of Computer Programming, an ongoing multi-volume series of books whose publication began more than fifty years ago, and the digital typesetting system TeX, which, in a recent profile of Knuth, the New York Times' Siobhan Roberts describes as "the gold standard for all forms of scientific communication and publication." Some, Roberts writes, consider TeX "Dr. Knuth’s greatest contribution to the world, and the greatest contribution to typography since Gutenberg." At the core of his lifelong work is an idea called "literate programming," which emphasizes "the importance of writing code that is readable by humans as well as computers — a notion that nowadays seems almost twee. Dr. Knuth has gone so far as to argue that some computer programs are, like Elizabeth Bishop’s poems and Philip Roth’s American Pastoral, works of literature worthy of a Pulitzer." Knuth's mind, technical achievements, and style of communication have earned him the informal title of "the Yoda of Silicon Valley." That appellation also reflects a depth of technical wisdom only attainable by getting to the very bottom of things, which in Knuth's case means fully understanding how computer programming works all the way down to the most basic level. (This in contrast to the average programmer, writes Roberts, who "no longer has time to manipulate the binary muck, and works instead with hierarchies of abstraction, layers upon layers of code — and often with chains of code borrowed from code libraries.) Now everyone can get more than a taste of Knuth's perspective and thoughts on computers, programming, and a host of related subjects on the Youtube channel of Stanford University, where Knuth is now professor emeritus (and where he still gives informal lectures under the banner "Computer Musings"). Stanford's online archive of Donald Knuth Lectures now numbers 110, ranging across the decades and covering such subjects as the usage and mechanics of TeX, the analysis of algorithms, and the nature of mathematical writing. "I am worried that algorithms are getting too prominent in the world,” he tells Roberts in the New York Times profile. “It started out that computer scientists were worried nobody was listening to us. Now I’m worried that too many people are listening." But having become a computer scientist before the field of computer science even had a name, the now-octogenarian Knuth possesses a rare perspective to which anyone in 21st-century technology could certainly benefit from exposure. Related Content: Free Online Computer Science Courses 50 Famous Academics & Scientists Talk About God The Secret History of Silicon Valley When J.M. Coetzee Secretly Programmed Computers to Write Poetry in the 1960s Introduction to Computer Science and Programming: A Free Course from MIT Peter Thiel’s Stanford Course on Startups: Read the Lecture Notes Free Online Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Watch 110 Lectures by Donald Knuth, “the Yoda of Silicon Valley,” on Programming, Mathematical Writing, and More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

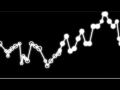

| 5:12p | Visualizing the Bass Playing Style of Motown’s Iconic Bassist James Jamerson: “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” “For Once in My Life” & More As part of Motown’s Funk Brothers house band, James Jamerson was the bubbling bass player behind hundreds of hit records from Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, The Supremes, Martha and the Vandellas, and plenty more. His licks duck and dive and weave like Ali but never get in the way of the melody or the rest of the band. Paul McCartney was an early fan, but for the general public, Jamerson was not a household name for decades--Motown never listed the Wrecking Crew in its credits--until much later when music journalists and filmmakers pushed him into the spotlight. But his style is so identifiable that YouTube channel Scott’s Bass Lessons has several videos about the man, explaining in detail how Jamerson produced that sound. Jamerson used a Precision Bass made by Fender, heavy flat wound strings that gave it those thick tones, and a very high action (i.e. how tight the strings are). So high in fact, that many contemporaries said his bass was impossible to play. (The tightness had warped the neck of the instrument.) He also placed foam under the bridge, and played high on the body with only his index finger, “the hook” as they used to call it. The other peculiarity of Jamerson’s recordings it that he plugged straight into the recording deck, instead of recording his amp. (McCartney started doing this in the middle of the Beatles’ career as well.) This led to a very compressed sound that helped his playing stand out in the mix. As you can see from these visualizations, Jamerson never stays still. If he could play a note on an open string he would (instead of moving over a fret), and that led to a fluid journey over the neck. On something like “I Was Made to Love Her,” Jamerson always makes sure to head up to double the sitar-like riff at the end of the verse: While on “For Once In My Life,” he uses the steady groove of the band (not heard on the video, but listen here) as a jumping off point of some very tricky rhythms. And though it’s complex, it never gets in the way, nor does it feel flashy or indulgent. Jamerson rarely changed strings, only if they broke, and he didn’t really look after his “black beauty” bass. Asked why, he said, “The dirt keeps the funk.” Related Content: How Carol Kaye Became the Most Prolific Session Musician in History The “Amen Break”: The Most Famous 6-Second Drum Loop & How It Spawned a Sampling Revolution Every Appearance James Brown Ever Made On Soul Train. So Nice, So Nice! Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW's Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here. Visualizing the Bass Playing Style of Motown’s Iconic Bassist James Jamerson: “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” “For Once in My Life” & More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/01/24 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |