[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, February 4th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 3:00p | How Dorothea Lange Shot, Migrant Mother, Perhaps the Most Iconic Photo in American History

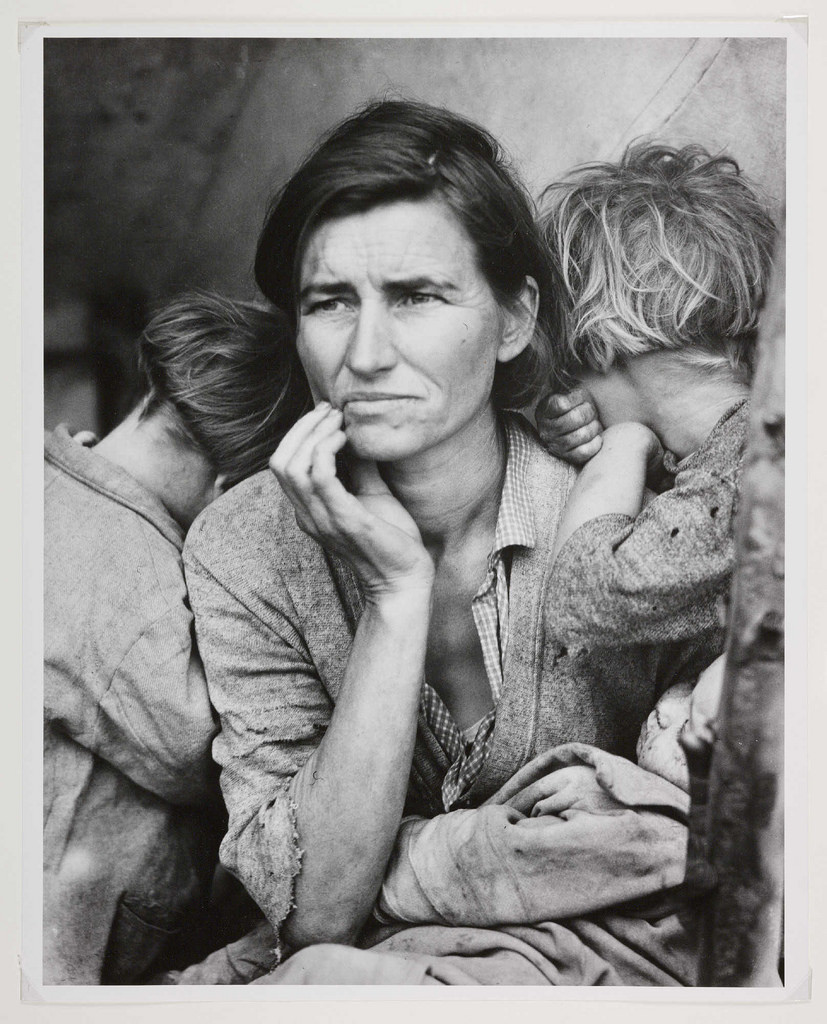

When we visualize the Great Depression, we think first of one woman: Native American migrant worker Florence Owens Thompson. Few of us know her name, though nearly all of us know her face. For that we have another woman to thank: the photographer Dorothea Lange who during the Depression was working for the United States federal government, specifically the Farm Security Administration, on "a project that would involve documenting poor rural workers in a propaganda effort to elicit political support for government aid." That's how Evan Puschak, better known as the Nerdwriter, puts it in a video essay on Lange's famous 1936 photo of Thompson, Migrant Mother. (For best results, view the video below on a phone or tablet rather than on a standard computer screen.) Reaching the migrant workers' camp in Nipomo, California where Thompson and her children were staying toward the end of another long day of photography, Lange at first passed it by. Only about twenty miles later did she decide to turn the car around and see what material the 2,500 to 3,500 "pea pickers" there might offer. She stayed only ten minutes, but in that time captured what Puschak calls the photograph that "came to define the Depression in the American consciousness" — it even heads the Great Depression's Wikipedia page — and "became the archetypal image of struggling families in any era." Over time, Migrant Mother has also become "one of the most iconic pictures in the history of photography." But Lange didn't get it right away: it was actually the sixth portrait she took of Thompson, each one more powerful (and more able to "evoke sympathy from voters that would translate into political support") than the last. Puschak takes us through each of these, marking the changes in composition that led to the photograph we can all call to mind immediately. "A lesser photographer would have milked the children's faces for their sympathetic potential," for instance, but having them turn away "communicates that message of family" without "taking away from the central face, or the eyes, which seem at last to let down their guard as they search the distance and worry." These and other actively made choices (including the removal of Thompson's distracting left thumb in the darkroom) mean that "there is very little spontaneous in this iconic image of so-called documentary photography," but "whether that diminishes its power is up to you. For me, being able to actually see the steps of Lange's craft enhances her work." Whatever Lange's process, the product defined an era, and upon publication convinced the government to send 20,000 pounds of food to Nipomo — though by that point Thompson herself, who ultimately succeeded in providing for her family and lived to the age of 80, had moved on. Related Content: 478 Dorothea Lange Photographs Poignantly Document the Internment of the Japanese During WWII Yale Launches an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression Found: Lost Great Depression Photos Capturing Hard Times on Farms, and in Town “A Great Day in Harlem,” Art Kane’s Iconic Photo of 57 Jazz Legends, Celebrates Its 60th Anniversary Edward Hopper’s Iconic Painting Nighthawks Explained in a 7-Minute Video Introduction Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. How Dorothea Lange Shot, Migrant Mother, Perhaps the Most Iconic Photo in American History is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

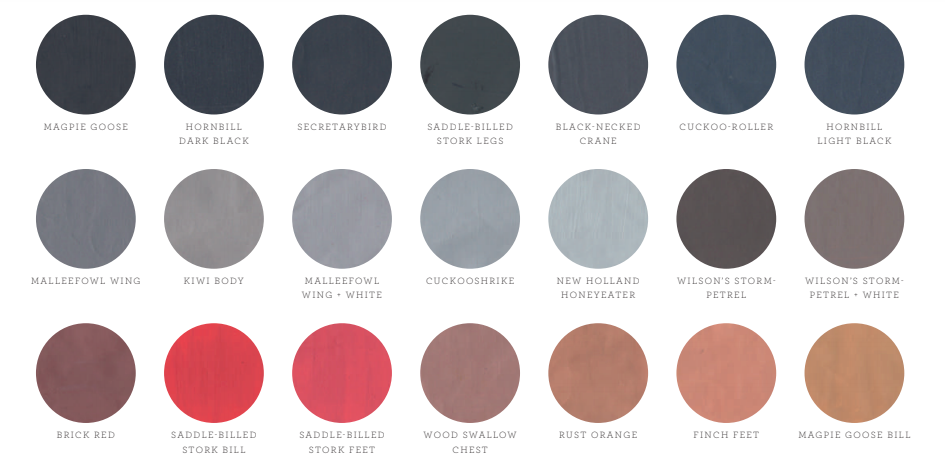

| 6:30p | Explore an Interactive Version of The Wall of Birds, a 2,500 Square-Foot Mural That Documents the Evolution of Birds Over 375 Million Years Now, this avian Vatican also has its own Michelangelo. And the Class of Aves has its very own avian Pantone chart, created by science illustrator Jane Kim in service of her 2,500 square-foot Wall of Birds mural at Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology. The custom chart’s fifty-one colors comprise about 90 percent of the finished work. A palette of thirteen Golden Fluid Acrylics supplied the jewel-toned accents so thrilling to birdwatchers.

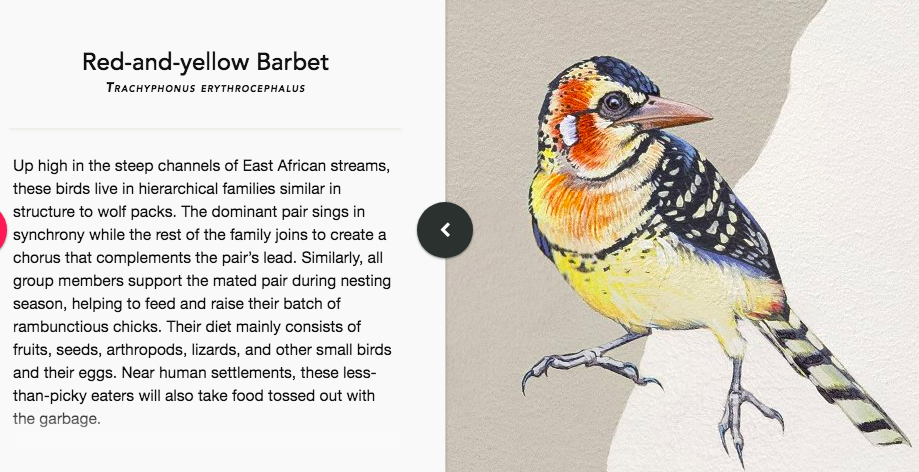

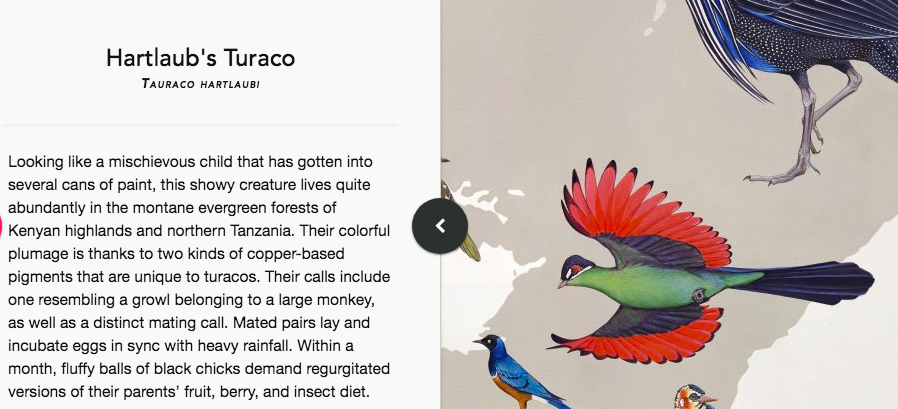

Along the way, Kim absorbed a tremendous amount of information about the how and why of bird feather coloration: The iridescence on the neck and back of the Superb Starling comes not from pigment, but from structural color. The starling’s outer feathers are constructed in a way that refracts light like myriad prisms, making the bird appear to shimmer. The eponymous coloring of the Lilac-breasted Roller results from a different kind of structural color, created when woven microstructures in the feathers, called barbs and barbules, reflect only the shorter wavelengths of light like blue and violet. The primary colors that lend their name to the Red-and-yellow Barbet are derived from a class of pigments called carotenoids that the bird absorbs in its diet. These are the same compounds that turn flamingos’ feathers pink. As a member of the family Musophagidae, the Hartlaub’s Turaco displays pigmentation unique in the bird world. Birds have no green pigmentation; in most cases, verdant plumage is a combination of yellow carotenoids and blue structural color. Turacos are an exception, displaying a green, copper-based pigment called turacoverdin that they absorb in their herbivorous diet. The flash of red on the Hartlaub’s underwings comes from turacin, another copper-based pigment unique to the family.

Kim also boned up on her subjects’ mating rituals, dietary habits, song styles, and male/female differences prior to inscribing the 270 life-size, lifelike birds onto the lab’s largest wall. She examined specimens from the center's collection and reviewed centuries’ worth of field observations. (The seventeenth-century English naturalist John Ray dismissed the hornbill family as having a “foul look,” a colonialism that ruffled Kim’s own feathers somewhat. In retaliation, she dubbed the Great Hornbill, “the Cyrano of the Jungle” owing to his “tequila-sunrise-hued facial phallus,” and selected him as the cover boy for her book about the mural.)

Research and preliminary sketching consumed an entire year, after which it took 17 months to inscribe 270 life-size creatures—some long extinct—onto the lab’s main wall. The birds are set against a greyscale map of the world, and while many are depicted in flight, every one save the Wandering Albatross has a foot touching its continent of origin. Those who can’t visit the Wall of Birds (official title: From So Simple a Beginning) in person, can log some digital birdwatching using a spectacular interactive web-based version of the mural that provides plenty of information about each specimen, some of it literary. (The aforementioned Albatross’ entry contains a passing reference to The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.) Explore the Wall of Birds’ interactive features here. You can download a free chapter of The Wall of Birds: One Planet, 243 Families, 375 Million Years by subscribing to Kim’s mailing list here. Via Hyperallergic Related Content: Cornell Launches Archive of 150,000 Bird Calls and Animal Sounds, with Recordings Going Back to 1929 What Kind of Bird Is That?: A Free App From Cornell Will Give You the Answer Modernist Birdhouses Inspired by Bauhaus, Frank Lloyd Wright and Joseph Eichler Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. See her onstage in New York City February 11 for Theater of the Apes book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Explore an Interactive Version of The Wall of Birds, a 2,500 Square-Foot Mural That Documents the Evolution of Birds Over 375 Million Years is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

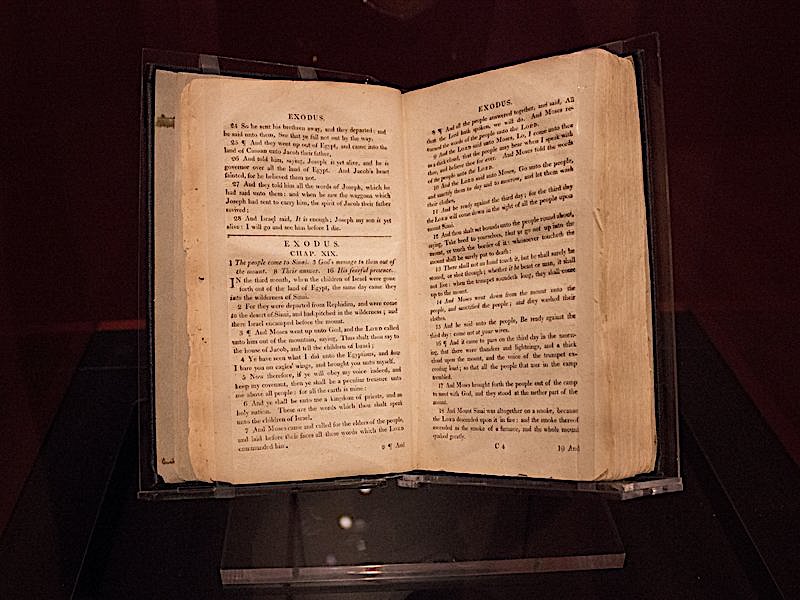

| 7:00p | The “Slave Bible” Removed Key Biblical Passages In Order to Legitimize Slavery & Discourage a Slave Rebellion (1807)

Photo via the Museum of the Bible In an 1846 speech to the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, Frederick Douglass summed up the twisted bond between slavery and religion in the U.S. He began with a short summary of atrocities that were legal, even encouraged, against enslaved people in Virginia and Maryland, including hanging, beheading, drawing and quartering, rape, “and this is not the worst.” He then made his case:

Douglass did not intend his statement to be taken as an indictment of Christianity, but rather the hypocrisy of American religion, both that “of the Southern states” and of “the Northern religion that sympathizes with it.” He speaks, he says, to reject “the slaveholding, the woman-whipping, the mind-darkening, the soul-destroying religion” of the country, while professing a religion that “makes its followers do unto others as they themselves would be done by.” Douglass harshly condemns slave society in the U.S., but, perhaps given his audience, he also politically elides the extensive role many churches in the British Empire played in the slave trade and Atlantic slave economy—a continued role, to Douglass’s dismay, as he found during his UK travels in the 1840s. I'm not sure if he knew that forty years earlier, British missionaries traveled to slave plantations in the Caribbean armed with heavily-edited Bibles in which “any passage that might incite rebellion was removed,” as Brigit Katz writes at Smithsonian. But he would hardly have been surprised. The use of religion to terrorize and control rather than liberate was something Douglass understood well, having for decades keenly observed slaveowners finding what they needed in the text and ignoring or suppressing the rest. In 1807, the Society for the Conversion of Negro Slaves went so far as to literally excise the central narrative of the Old Testament, creating an entirely different book for use by missionaries to the West Indies. “Gone,” Katz points out, “were references to the exodus of enslaved Israelites from Egypt," references that were integral to the self-understanding of millions of Diaspora Africans. Gone also were verses that might explicitly contradict the few proof texts slaveholders quoted to justify themselves. Especially dangerous was Exodus 21:16: “And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death.” The typical 66 books of a Protestant Bible had been reduced to parts of just 14. How is it possible to publish a Bible without what amounts to the mythic origin story of ancient Israel? One answer is that this was a different religion, one whose aim, says Anthony Schmidt, curator of the Museum of the Bible, was to make “better slaves.”

The "Slave Bible" did not cut out the subject completely. Joseph’s enslavement in Egypt remains, but this is likely as an example, says Schmidt, of someone who “accepts his lot in life" and is rewarded for it, a story U.S. churches used in a similar fashion. Passages in the New Testament that seemed to emphasize equality were cut, as was the entire book of Revelation. The infamous Ephesians 6:5—“servants be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, in fear and trembling”—remained. Whether or not the Bible really did sanction slavery is a question still up for debate—and maybe an unanswerable one given differences in interpretive frameworks and the patchwork nature of the disparate, redacted texts stitched together as one. But the fact that British and American churches deliberately used it as a weaponized tool of propaganda and indoctrination is beyond dispute. The so-called “Slave Bible” is both a fascinating historical artifact, a very literal symbol of a practice that was integral to the institution of slavery—the total control of the narrative. Such practices became more extreme after the Haitian Revolution and the many bloody slave revolts in the U.S., as the planter class became increasingly desperate to hold on to power. One of only three extant “Slave Bibles,” the abridged version—called Parts of the Holy Bible, selected for the use of the Negro Slaves, in the British West-India Islands—is now on display at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC, on loan from Fisk University. In the NPR interview above, Schmidt explains the book’s history to All Things Considered’s Michel Martin, who herself describes the text’s purpose in the most concise way: “To associate human bondage and human slavery with obedience to the higher power.” via The Smithsonian Related Content: The Atlantic Slave Trade Visualized in Two Minutes: 10 Million Lives, 20,000 Voyages, Over 315 Years Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The “Slave Bible” Removed Key Biblical Passages In Order to Legitimize Slavery & Discourage a Slave Rebellion (1807) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 9:20p | The Case for Why Ringo Starr Is One of Rock’s Greatest Drummers As far as I’m concerned, debate over whether or not Ringo Starr is a good drummer is over, done with, settled. How is it possible that some of the greatest recorded music of the 20th century, with some of the most distinctive rhythms, fills, and drum breaks in pop music, could have come from a mediocre musician? The standard response has been to allege that Starr’s best parts were played by someone else. In a handful of recordings—though I won’t argue over which ones—it seems he might have been replaced, for whatever reason. But Ringo could do more than hold his own. He was something rarer and more valuable than any studio musician. He remains one of the most distinctively musical drummers on record. What does that mean? It means he intuited exactly what a song needed, and what it didn’t. He used what Buddy Rich called his “adequate” abilities (a compliment, I’d say, coming from Buddy Rich) to serve the songs best, finding ways to enhance the structures and arrangements with drum parts that are as uniquely memorable as the melodies and harmonies. His humility and sense of humor come through in his tasteful, yet dynamic playing. I say this as a serious Ringo fan, but if you, or someone you know, needs convincing, don’t take my word for it. Take it from George Harrison, above, and from skilled drummers Sina and Brandon Koo. What are Sina’s credentials for making a pro-Ringo case? Well, for one thing, her father played in Germany’s biggest Beatles tribute band, the Silver Beatles. Also, she’s a very good musician who has memorized Ringo's repertoire and can explain it well. Above, she demonstrates how his uncomplicated grooves complement the songs, so much so they have become iconic in their own right. (To skirt copyright issues, Sina plays along to convincing covers by her dad’s band.) Ringo’s drum pattern for “In My Life,” for example, she says “is absolutely unique, nobody ever played this before. It’s truly original and the song won’t work with any other drum part.” If you were to write a new song around the drums alone, it would probably come out sounding just like "In My Life." As Harrison remarks at the top, “he’s very good because he’ll listen to the song once, and he knows exactly what to play.” Virtuoso drummer Brandon Koo makes the case for Ringo as a good drummer, above, after a brief defense of much-maligned White Stripes drummer Meg White. He, too, chooses “In My Life” to show how “Ringo lays it down” with maximum feel and efficiency, deftly but subtly changing things up in nearly every phrase of the song. Conversely—in an exaggerated counterexample—Koo shows what a technically-skilled, but unmusical, drummer might do, namely trample over the delicate guitars and vocals with an aggressive attack and distracting, unnecessary fills and cymbal crashes. “A good drummer is a drummer who knows how to play, number one, for the music.” If these clear demonstrations fail to sway, maybe some celebrity endorsements will do. Just above, in a video made by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to celebrate an exhibit of Ringo’s famous drum kit, see Dave Grohl, Taylor Hawkins, Stewart Copeland, Questlove, Tre Cool, Max Weinberg, Chad Smith, and more pay tribute. Grohl describes him as the “king of feel,” Smith talks about his “knack for coming up with really interesting musical parts that became rhythmic hooks.” In the span of just three minutes, we get a sense of exactly why the most famous drummers in rock and roll admire Ringo. Millions of drummers have come and gone since The Beatles’ day, most of them influenced by Ringo, as Weinberg says. And not one of them has ever played like Ringo Starr. “You hear his drumming,” says Grohl, “and you know exactly who it is.” Hear how his style evolved right along with the band's songwriting in Kye Smith's chronological drum medley of Beatles hits below. Related Content: How Can You Tell a Good Drummer from a Bad Drummer?: Ringo Starr as Case Study Isolated Drum Tracks From Six of Rock’s Greatest: Bonham, Moon, Peart, Copeland, Grohl & Starr Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness. The Case for Why Ringo Starr Is One of Rock’s Greatest Drummers is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/02/04 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |