[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, February 20th, 2019

| Time | Event |

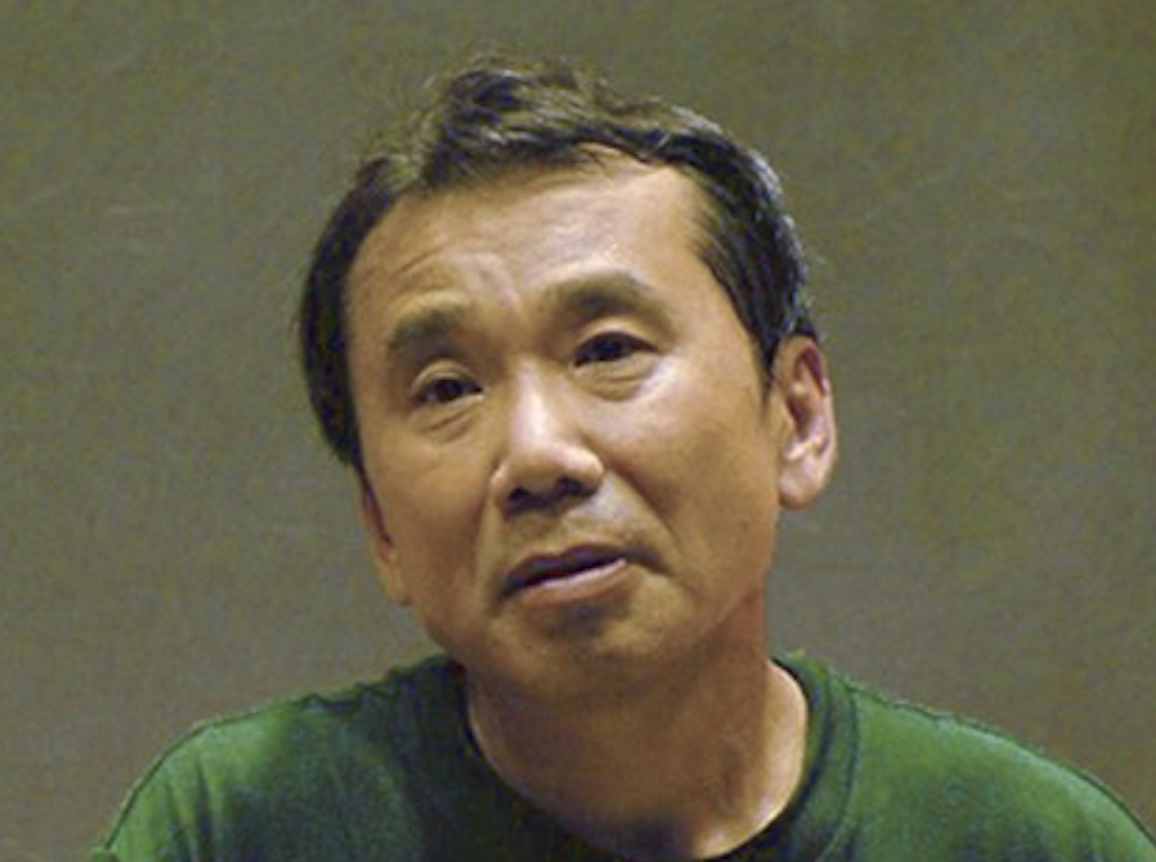

| 12:00p | Haruki Murakami Announces an Archive That Will House His Manuscripts, Letters & Collection of 10,000+ Vinyl Records

Image by wakarimasita, via Wikimedia Commons It has become the norm for notable writers to bequeath documents related to their work, and even their personal correspondence, to an institution that promises to maintain it all, in perpetuity, in an archive open to scholars. Often the institution is located at a university to which the writer has some connection, and the case of the Haruki Murakami Library at Tokyo's Waseda University is no exception: Murakami graduated from Waseda in 1975, and a dozen years later used it as a setting in his breakthrough novel Norwegian Wood. That book's portrayal of Waseda betrays a somewhat dim view of the place, but Murakami looks much more kindly on his alma mater now than he did then: he must, since he plans to entrust it with not just all his papers but his beloved record collection as well. If you wanted to see that collection today, you'd have to visit him at home. "I exchanged my shoes for slippers, and Murakami took me upstairs to his office," writes Sam Anderson, having done just that for a 2011 New York Times Magazine profile of the writer. "This is also, not coincidentally, the home of his vast record collection. (He guesses that he has around 10,000 but says he’s too scared to count.)" Having announced the plans for Waseda's Murakami Library at the end of last year, Murakami can now rest assured that the counting will be left to the archivists. He hopes, he said at a rare press conference, "to create a space that functions as a study where my record collection and books are stored." In his own space now, he explained, he has "a collection of records, audio equipment and some books. The idea is to create an atmosphere like that, not to create a replica of my study." Some of Murakami's stated motivation to establish the library comes out of convictions about the importance of "a place of open international exchanges for literature and culture" and "an alternative place that you can drop by." And some of it, of course, comes out of practicality: "After nearly 40 years of writing, there is hardly any space to put the documents such as manuscripts and related articles, whether at my home or at my office." "I also have no children to take care of them," Murakami added, "and I didn’t want those resources to be scattered and lost when I die." Few of his countless readers around the world can imagine that day coming any time soon, turn 70 though Murakami did last month, but many are no doubt making plans even now for a trip to the Waseda campus to see what shape the Murakami Library takes during the writer's lifetime, especially since he plans to take an active role in what goes on there. "Murakami is also hoping to organize a concert featuring his collection of vinyl records," notes The Vinyl Factory's Gabriela Helfet. Until he does, you can have a listen to the playlists, previously featured here on Open Culture, of 96 songs from his novels and 3,350 from his record collection — but you'll have to recreate the atmosphere of his study yourself for now. Related Content: A 3,350-Song Playlist of Music from Haruki Murakami’s Personal Record Collection A 26-Hour Playlist Featuring Music from Haruki Murakami’s Latest Novel, Killing Commendatore Haruki Murakami’s Passion for Jazz: Discover the Novelist’s Jazz Playlist, Jazz Essay & Jazz Bar Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Haruki Murakami Announces an Archive That Will House His Manuscripts, Letters & Collection of 10,000+ Vinyl Records is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | How the Mona Lisa Went From Being Barely Known, to Suddenly the Most Famous Painting in the World (1911) Is the Mona Lisa really “ten times better than every other painting”? No one seriously believes this, and how would anyone measure such a thing? There may be no such critical scale, but there is a popular one. The Louvre, where the famous Leonardo da Vinci—maybe the most famous painting of all time—hangs, says that 80 percent of its visitors come just to see the Mona Lisa. Her enigmatic smile adorns merchandise the world wide. Books, essays, documentaries, songs, coffee mugs—hers may be the most recognizable face in Western art. Learn in the Vox video above, however, how that fame came about as the result of a different kind of publicity—coverage of the Mona Lisa theft in 1911. It became an overnight sensation. “Before its theft,” notes NPR, “the ‘Mona Lisa’ was not widely known outside the art world. Leonardo da Vinci painted it in 1507, but it wasn't until the 1860s that critics began to hail it as a masterwork of Renaissance painting. And that judgment didn't filter outside a thin slice of French intelligentsia.” Though the painting once hung in the bedroom of Napoleon, in the 19th century, it “wasn’t even the most famous painting in its gallery, let alone in the Louvre,” historian James Zug tells All Things Considered. Writing at Vox, Phil Edwards describes how an essay by Victorian art critic Walter Pater elevated the Mona Lisa among art critics and intellectuals like Oscar Wilde. His overwrought prose “popped up in guidebooks to the Louvre and reading clubs in Paducah.” Yet it was not art criticism that sold the painting to the general public. It was the intrigue of an art heist. In 1911, an Italian construction worker, Vincenzo Perugia, was working for the firm Cobier, engaged in putting several paintings, including the Mona Lisa, under glass. While at the Louvre, he hatched a plan to steal the painting with two accomplices, brothers Vincenzo and Michele Lancelotti. The crime was literally notorious overnight. The theft occurred on Monday morning, August 21. By late Tuesday, the story had been picked up by major newspapers all over the world. Pablo Picasso and poet Guillaume Apollinaire went on trial for the theft (their case was dismissed). Conspiracy theories popped up all over the place, claiming, as per usual, that the whole thing was a hoax or a distraction engineered by the French government. “Wanted posters for the painting appeared on Parisian walls,” Zug writes at Smithsonian. “Crowds massed at police headquarters. Thousands of spectators, including Franz Kafka, flooded the Salon Carré when the Louvre reopened after a week to stare at the empty wall with its four lonely iron hooks.” Once the painting was restored, the crowds kept coming. Newspaper photos and police posters gave way to t-shirts and mousepads. The painting's undoubted excellence seemed incidental; it became, like Andy Warhol's soup cans, famous for being famous. Learn more about the Mona Lisa’s long strange trip through history in the short Great Big Story video above. Related Content: When Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire Were Accused of Stealing the Mona Lisa (1911) Mona Lisa Selfie: A Montage of Social Media Photos Taken at the Louvre and Put on Instagram Original Portrait of the Mona Lisa Found Beneath the Paint Layers of da Vinci’s Masterpiece Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How the Mona Lisa Went From Being Barely Known, to Suddenly the Most Famous Painting in the World (1911) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:00p | The History of Ancient Rome in 20 Quick Minutes: A Primer Narrated by Brian Cox Two thousand years ago, Rome was half the world. A thousand years before that, it was “a tiny tribal settlement of the Latins by the river Tiber.” So, what happened? An awful lot. But narrator Brian Cox makes the history and longevity of Ancient Rome seem simple in 20 minutes in the Arzamas video above, which brings the same talent for narrative compression as we saw in an earlier video we featured with Cox describing the history of Russian Art. This is a far more sprawling subject, but it’s one you can absorb in 20 minutes, if you’re satisfied with very broad outlines. Or, like one YouTube commenter, you can spend six hours, or more, pausing for reading and research after each morsel of information Cox tosses out. The story begins with trade—cultural and economic—between the Latins and the Etruscans to the north and Greeks to the south. Rome grows by adding populations from all over the world, allowing migrants and refugees to become citizens. Indeed, the great Roman epic, the Aeneid, relates its founding by refugees from Troy. From these beginnings come monumental innovations in building and engineering, as well as an alphabet that spread around the world and a language that spawned dozens of others. The Roman numeral system, an unwieldy way to do mathematics, nonetheless gave to the world the stateliest means of writing numbers. Rome gets the credit for these gifts to world civilization, but they originated with the Etruscans, along with famed Roman military discipline and style of government. After Tarquin, the last Roman king, committed one abuse too many, the Republic began to form, as did new class divides. Plebs fought Patricians for expanded rights, Senatus Populusque Romanus (SPQR)—the senate and the people of Rome—expressed an ideal of unity and political equality, of a sort. An age of imperial war ensues, conquered peoples are ostensibly made allies, not colonials, though they are also made slaves and supply the legions with “a never ending supply of recruits.” These sketches of major campaigns you may remember from your World Civ class: The Punic Wars with Carthage, and their commander Hannibal, conducted under the motto of Cato, the senator who beat the drums of war by repeating Carthago delenda est—Carthage must be destroyed. The conquering of Corinth and the absorption of Alexander’s Hellenist empire into Rome. The story of the Empire resembles that of so many others: tales of hubris, ferocious brutality, genocide, and endless building. But it is also a story of political genius, in which, gradually, those peoples brought under the banners of Rome by force were given citizenship and rights, ensuring their loyalty. Relative peace—within the borders of Rome, at least—could not hold, and the Republic imploded in civil wars and the ruination of a slave economy and extreme inequality. The wealthy gobbled up arable land. The tribunes of the people, the Gracchi brothers, suggested a redistribution scheme. The senators responded with force, killing thousands. Two mass-murdering conquering generals, Pompey and Julius Caesar, fought over Rome. Caesar crossed the Rubicon with his legions to take the city, assuming the title Imperator, a move that cost him his life. But his murder didn’t stop the march of Empire. Under his nephew Augustus, a dictator who called himself a senator, Rome spread, flourished, and established a 200-year Pax Romana, a time of thriving arts and culture, popular entertainments, and a well-fed populace. Augustus had learned from the Gracchi what neither the venal senatorial class nor so many subsequent emperors could. In order to rule effectively, you’ve got to have the people on your side, or have them so distracted, at least, by bread and circuses, that they won't bother to revolt. Watch the full video to learn about the next few hundred years, and learn more about Ancient Rome at the links below. Related Content: Play Caesar: Travel Ancient Rome with Stanford’s Interactive Map Rome Reborn: Take a Virtual Tour of Ancient Rome, Circa 320 C.E. An Interactive Map Shows Just How Many Roads Actually Lead to Rome Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The History of Ancient Rome in 20 Quick Minutes: A Primer Narrated by Brian Cox is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/02/20 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |