[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, March 6th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | John Cleese Revisits His 20 Years as an Ivy League Professor in His New Book, Professor at Large: The Cornell Years

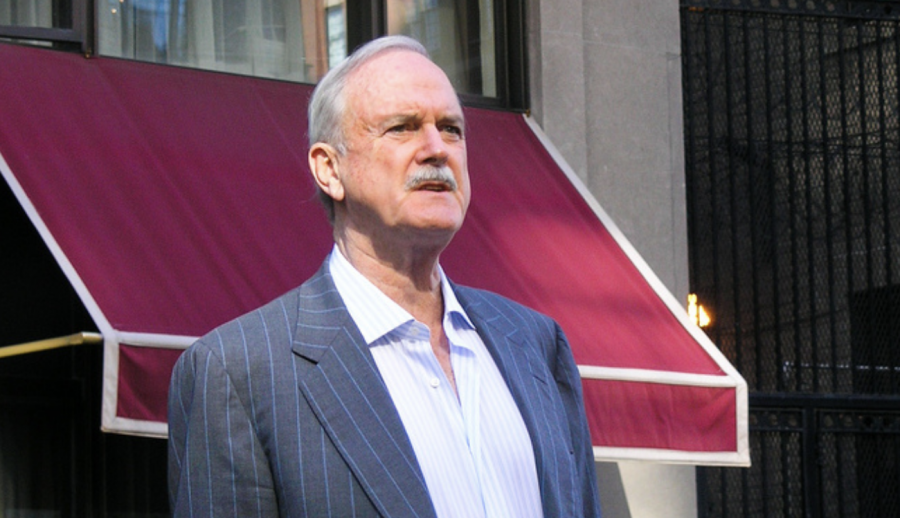

Creative Commons image by Paul Boxley It takes real intelligence to successfully make dumb comedy. John Cleese and his Monty Python colleagues are a premium example. You can call sketches like the “Ministry of Silly Walks” and “Dead Parrot” surrealist, and they are comparable to the absurdist stunts favored by certain early 20th century modern artists. But you can also call them very smart kinds of stupid, a description of some of the highest forms of comedy, I’d say, and one that applies to so much of Cleese’s best work, from the Pythons, to Fawlty Towers, to A Fish Called Wanda. We are moved by stupidity, Cleese believes, and silliness is the engine of good comedy. “Sometimes very, very silly things,” he says in the interview with Cornell University Press director Dean Smith below, "have the power to touch us deeply." Then he tells the old joke about a grasshopper named Norman.

Is Cleese still funny? Depends. Many listeners of a recent BBC Radio 4 show found his act a little stale. He has also come off lately as a “classic old man yelling at a cloud,” writes Fiona Sturges at The Guardian. (He called, surely in jest, for the hanging of EU president Jean Claude Juncker, for example, during the Brexit campaign). In curmudgeonly interviews, he complains about hypersensitivity with examples of jokes contemporary audiences simply don’t find amusing, or at least not coming from him. Cleese has railed about the evils of political correctness, especially on college campuses, while spending the past 20 years as a “professor-at-large” on the prestigious campus of Cornell University, where he has delivered “incredibly popular events and classes—including talks, workshops, and an analysis of A Fish Called Wanda and The Life of Brian.”

These appearances draw hundreds of people, and their enormous popularity should offer Cleese some reassurance that he may not need to fear censorship, and that his wit—while it might not be as well appreciated in today's mass entertainment—still has plenty of currency in places where smart people gather. From seminars on script writing to lectures on psychology and human development, Cleese’s appearances at Cornell lead to riveting, sometimes hilarious, and often controversial conversations.

In the episodes here from the Cornell University Press podcast, you can hear Cleese’s full conversation with Smith, part of the promotion of his 2018 book Professor at Large: The Cornell Years, in which he includes an interview with Princess Bride screenwriter William Goldman, a lecture about creativity called “Hare Brain, Tortoise Mind,” a discussion of facial recognition technology, and a talk on group dynamics with business students and faculty. Like Cleese’s mind, these lectures and discussions range far and wide, demonstrating, once again in his long career, that it takes real smarts to not only speak with ease on several academic subjects, but to understand the mechanics of stupidity. You can pick up a copy of Professor at Large: The Cornell Years here. Related Content: John Cleese Explains the Brain — and the Pleasures of DirecTV John Cleese’s Philosophy of Creativity: Creating Oases for Childlike Play Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness John Cleese Revisits His 20 Years as an Ivy League Professor in His New Book, Professor at Large: The Cornell Years is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 12:00p | 100-Year-Old Holocaust Survivor Helen Fagin Reads Her Letter About How Books Save Lives

"Could you imagine a world without access to reading, to learning, to books?" Helen Fagin, who poses that question, doesn't have to imagine it: she experienced that grim reality, and worse besides. "At twenty-one," she continues, "I was forced into Poland’s World War II ghetto, where being caught reading anything forbidden by the Nazis meant, at best, hard labor; at worst, death." There she operated a school in secret where she taught Jewish children Latin and mathematics, soon realizing that "what they needed wasn’t dry information but hope, the kind that comes from being transported into a dream-world of possibility." That hope, in Fagin's wartime experience, came from books. "I had spent the previous night reading Gone with the Wind — one of a few smuggled books circulated among trustworthy people via an underground channel, on their word of honor to read only at night, in secret." The next day she retold the story of Margaret Mitchell's novel in her clandestine classroom, where the students had expressed their desire for her to "tell us a book," and one young girl expressed a special gratitude, thanking Fagin "for this journey into another world." To hear how her story, and Fagin's, turned out, you can listen to the 100-year-old Fagin herself read the letter that tells the tale in the video above, and you can follow along with the text at Brain Pickings. Brain Pickings founder Maria Popova has included Fagin's letter in the new collection A Velocity of Being: Illustrated Letters to Children about Why We Read by 121 of the Most Inspiring Humans in Our World. The book contains "original illustrated letters about the transformative and transcendent power of reading from some immensely inspiring humans," Popova writes, from Jane Goodall and Marina Abramovi? to Yo-Yo Ma and David Byrne to Judy Blume and Neil Gaiman — the last of whom, as Fagin's cousin, offered Popova the connection to this centenarian living testament to the power of reading. There are times when dreams sustain us more than facts," writes Fagin, one suspects as much to the adult readers of the world as to the children. "To read a book and surrender to a story is to keep our very humanity alive." via Brain Pickings Related Content: 96-Year-Old Holocaust Survivor Fronts a Death Metal Band Brian Eno Lists 20 Books for Rebuilding Civilization & 59 Books For Building Your Intellectual World Stewart Brand’s List of 76 Books for Rebuilding Civilization Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. 100-Year-Old Holocaust Survivor Helen Fagin Reads Her Letter About How Books Save Lives is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:07p | Download the ModulAir, a Free Polyphonic Synthesizer, and Make Your Own Electronic Sounds Over the years, we've talked a fair share about electronic music--from the earliest days of the genre, through contemporary times. Now, we give you a chance to make your own electronic sounds. According to Synthopia, a portal devoted to electronic music, "Full Bucket Music has released ModulAir 1.0 – a free polyphonic modular synthesizer for Mac & Windows." (For the uninitiated, a polyphonic synthesizer--versus a monophonic one--can play multiple notes at once.) The ModulAir "is a modular polyphonic software synthesizer for Microsoft Windows (VST) and Apple macOS (VST/AU), written in native C++ code for high performance and low CPU consumption." Watch a demo above, and download it here. Related Content: Everything Thing You Ever Wanted to Know About the Synthesizer: A Vintage Three-Hour Crash Course The Mastermind of Devo, Mark Mothersbaugh, Presents His Personal Synthesizer Collection Download the ModulAir, a Free Polyphonic Synthesizer, and Make Your Own Electronic Sounds is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

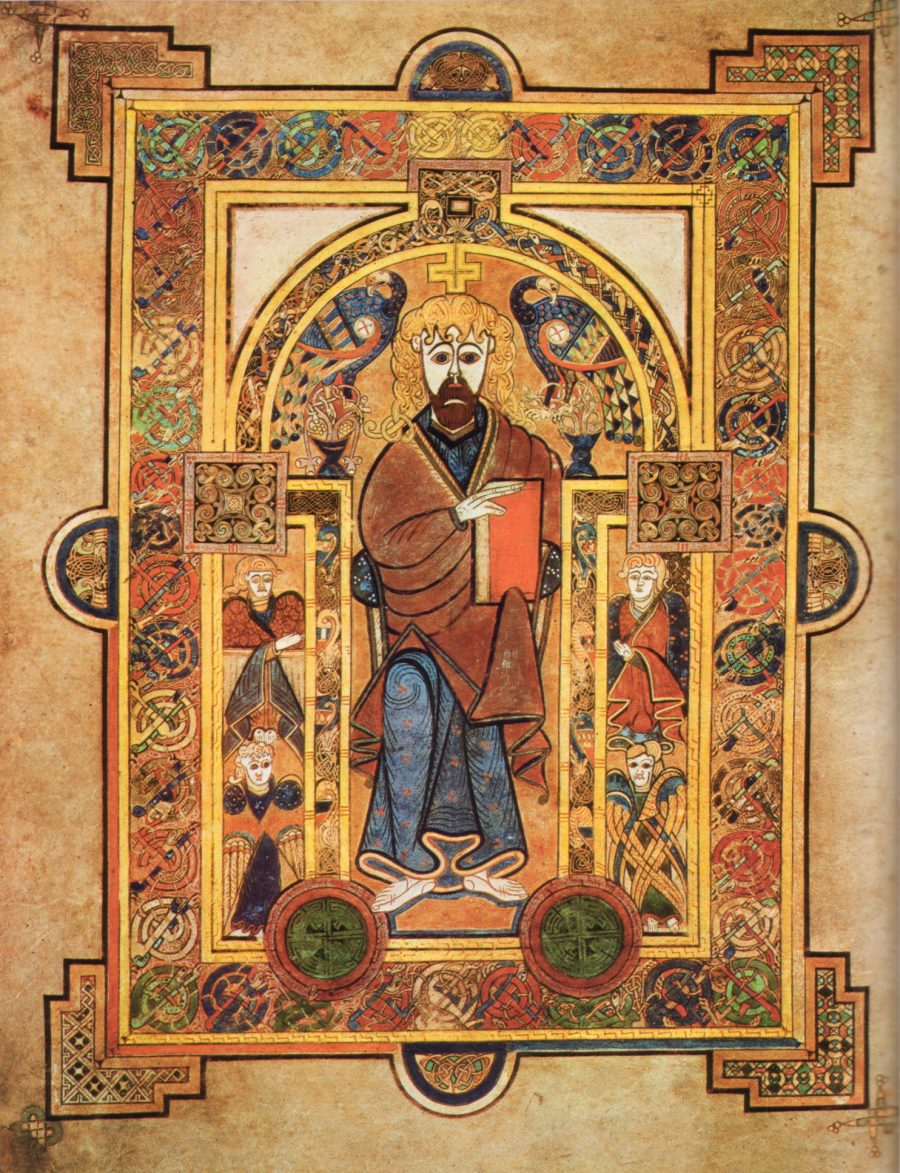

| 6:59p | The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Is Now Digitized & Put Online

If you know nothing else about medieval European illuminated manuscripts, you surely know the Book of Kells. “One of Ireland’s greatest cultural treasures” comments Medievalists.net, “it is set apart from other manuscripts of the same period by the quality of its artwork and the sheer number of illustrations that run throughout the 680 pages of the book.” The work not only attracts scholars, but almost a million visitors to Dublin every year. “You simply can’t travel to the capital of Ireland,” writes Book Riot’s Erika Harlitz-Kern, “without the Book of Kells being mentioned. And rightfully so.” The ancient masterpiece is a stunning example of Hiberno-Saxon style, thought to have been composed on the Scottish island of Iona in 806, then transferred to the monastery of Kells in County Meath after a Viking raid (a story told in the marvelous animated film The Secret of Kells). Consisting mainly of copies of the four gospels, as well as indexes called “canon tables,” the manuscript is believed to have been made primarily for display, not reading aloud, which is why “the images are elaborate and detailed while the text is carelessly copied with entire words missing or long passages being repeated.” Its exquisite illuminations mark it as a ceremonial object, and its “intricacies,” argue Trinity College Dublin professors Rachel Moss and Fáinche Ryan, “lead the mind along pathways of the imagination…. You haven’t been to Ireland unless you’ve seen the Book of Kells.” This may be so, but thankfully, in our digital age, you need not go to Dublin to see this fabulous historical artifact, or a digitization of it at least, entirely viewable at the online collections of the Trinity College Library. The pages, originally captured in 1990, “have recently been rescanned,” Trinity College Library writes, using state of the art imaging technology. These new digital images offer the most accurate high resolution images to date, providing an experience second only to viewing the book in person.” What makes the Book of Kells so special, reproduced “in such varied places as Irish national coinage and tattoos?” ask Professors Moss and Ryan. “There is no one answer to these questions.” In their free online course on the manuscript, these two scholars of art history and theology, respectively, do not attempt to “provide definitive answers to the many questions that surround it.” Instead, they illuminate its history and many meanings to different communities of people, including, of course, the people of Ireland. “For Irish people,” they explain in the course trailer above, “it represents a sense of pride, a tangible link to a positive time in Ireland’s past, reflected through its unique art.” But while the Book of Kells is still a modern “symbol of Irishness,” it was made with materials and techniques that fell out of use several hundred years ago, and that were once spread far and wide across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. In the video above, Trinity College Library conservator John Gillis shows us how the manuscript was made using methods that date back to the “development of the codex, or the book form.” This includes the use of parchment, in this case calf skin, a material that remembers the anatomical features of the animals from which it came, with markings where tails, spines, and legs used to be. The Book of Kells has weathered the centuries fairly well, thanks to careful preservation, but it’s also had perhaps five rebindings in its lifetime. “In its original form,” notes Harlitz-Kern, the manuscript “was both thicker and larger. Thirty folios of the original manuscript have been lost through the centuries and the edges of the existing manuscript were severely trimmed during a rebinding in the nineteenth century.” It remains, nonetheless, one of the most impressive artifacts to come from the age of the illuminated manuscript, “described by some,” says Moss and Ryan, “as the most famous manuscript in the world.” Find out why by seeing it (virtually) for yourself and learning about it from the experts above. Related Content: Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Is Now Digitized & Put Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/03/06 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |