[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, April 2nd, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 6:26a | The Assassination of Jamal Khashoggi: A New Documentary "It’s been six months since agents from Saudi Arabia killed the Washington Post columnist. What has been done in the aftermath?" In this documentary, The Assassination of Jamal Khashoggi, The Washington Post examines Khashoggi’s writings, his killing inside the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul and the Trump administration’s response. Follow Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. If you'd like to support Open Culture and our mission, please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us provide the best free cultural and educational materials. The Assassination of Jamal Khashoggi: A New Documentary is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00a | See Classic Performances of Joni Mitchell from the Very Early Years–Before She Was Even Named Joni Mitchell (1965/66) A photograph of two old friends—Joni Mitchell and David Hockney—holding hands at Hockney’s L.A. solo exhibition took over the internet for a moment, for sentimental reasons Guy Trebay laid out in The New York Times. These include the fact that “Ms. Mitchell has seldom been seen in public since she says she was given a diagnosis of Morgellons disease, and suffered a brain aneurysm in 2015,” and “despite the presence of the cane she uses since having learned again to walk, Ms. Mitchell appears radiant and robust.” Trebay does not include another reason that comes to mind: the two elderly artists, in their sweaters and adorable matching snap-brim hats, look like regular old folks on the way to a weekly chess match in the park. It’s a humanizing portrait of two giants of the art and music world, two people who, despite their wealth and fame, seem imminently down-to-earth and approachable; a warm and cheerful image, says Irish poet Sean Hewitt, who first shared it on Twitter, of “two successful people enjoying their old age.” Doesn't everyone especially want that for Joni Mitchell? Of all the beloved septuagenarian stars on the public’s radar these days, Mitchell garners more well-wishes than anyone—rallying generations of stars and musicians for a 75th birthday tribute concert last November. The show appeared in theaters (see a trailer below) and has been released as a superb album of live covers called Joni 75. So much of the love for Mitchell—her undisputed brilliance as a songwriter, guitarist, and performer notwithstanding—has to do with the amount of personal pain she overcame to make it as an artist. Born Roberta Joan Anderson in Alberta, Canada, her early struggles gave her musical voice so much poignancy and authenticity. As she herself has said, “I wouldn’t have pursued music but for trouble.” A bout with polio at age nine, a push against her parents' expectations to claim her identity as a visual artist and musician... then, at age 20, Mitchell’s boyfriend left her, “three months pregnant in an attic room with no money and winter coming on,” she later wrote. She gave up the baby for adoption, and the decision haunted her for years. In 1982’s “Chinese Café,” she sang “Your kids are coming up straight / My child’s a stranger / I bore her / But I could not raise her.” The following year, 1966, she married American folk singer Chuck Mitchell, took the name we know her by, and left Canada for the first time to make musical history. But first, she appeared on a Canadian television program called Let’s Sing Out, hosted by folk singer Oscar Brand and recorded on college campuses across the country between 1963 and 1967. The first ’65 episode at the top captures Mitchell—then Joan Anderson—singing her unreleased “Born to Take the Highway” at the University of Manitoba, a prescient song that “imagined cars and women differently” than the typical road songs of “powerful muscle cars” and “jacked-up masculinity and sexual conquest,” writes the blog Women in Rock. “I was born to take the highway / I was born to chase a dream,” she sings, certainties that reverberate through her music and her life. Brand introduces Mitchell as an example of the movement in folk music toward the “self-written song.” She appears with him later on that same broadcast to sing “Blow Away the Morning Dew” (a young Dave Van Ronk also appeared on the show). In subsequent broadcasts in the compilation, we see "Joan Anderson" more confidently inhabit the persona that would propel her to fame first in Canada, then the States, then the world. She performs solo and with the Chapins, then, finally as Joni Mitchell, in two 1966 broadcasts. Find a tracklist of each classic performance below, and, if you haven’t already, take some time out to celebrate Mitchell's 75th by revisiting the beginnings of her career over fifty years ago.

October 4, 1965 - With The Chapins and Dave Van Ronk 00:00 - Opening 01:22 - Born to Take the Highway 04:25 - Blow Away the Morning Dew

October 4, 1965 - With The Chapins and Patrick Sky 07:52 - Opening 09:05 - Favorite Color 12:00 - Me and My Uncle

October 24, 1966 - With Bob Jason and Jimmy Driftwood 15:08 - Opening 17:20 - Just Like Me 20:15 - Urge for Going

October 24, 1966 - With Bob Jason and the Allen-Ward Trio 24:08 - Opening 25:05 - Night in the City 27:55 - Blue on Blue 30:30 - Let's Get Together (Allen-Ward Trio) 33:37 - Prithee, Pretty Maiden

Related Content: Joni Mitchell Sings an Achingly Pretty Version of “Both Sides Now” on the Mama Cass TV Show (1969) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness See Classic Performances of Joni Mitchell from the Very Early Years–Before She Was Even Named Joni Mitchell (1965/66) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Beauty of Brutalist Architecture: An Introduction in Six Videos Some people hate the massive concrete buildings known as Brutalist, but they at least approve of the style's name, resonant as it seemingly is with associations of insensitive, anti-humanist bullying. Those who love Brutalism also approve of the style's name, but for a different reason: they know it comes from the French béton brut, referring to raw concrete, that material most generously used in Brutalist buildings' construction. We've all seen Brutalist architecture, massively embodied by Boston City Hall, London's Barbican Centre, UC Berkeley's Wurster Hall, the University of Toronto's Robarts Library, FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C., or any other of the examples that have stood since the style's 1960s and 70s heyday. But now, as more get slated for demolition each year, it has fallen to Brutalism's enthusiasts to defend an architecture easily seen as indefensible. The aesthetic of Brutalism, says host Roman Mars in an episode of the podcast 99% Invisible on the style, "can conjure up associations with bomb shelters, Soviet-era or 'third-world' construction, but as harsh as it looks, concrete is an utterly optimistic building material." In the 1920s "concrete was seen as being the material that would change the world. The material seemed boundless — readily available in vast quantities, and concrete sprang up everywhere — on bridges, tunnels, highways, sidewalks, and of course, massive buildings." It "presented the most efficient way to house huge numbers of people, and government programs all over the world loved it — particularly Soviet Russia, but also later in Europe and North America." Philosophically, "concrete was seen as humble, capable, and honest—exposed in all its rough glory, not hiding behind any paint or layers." However noble the intentions behind these works of architecture, though, it didn't take humanity long to turn on Brutalism. Part of the problem had to do with the disrepair into which many of the highest-profile Brutalist buildings — social housing complexes, transit centers, government offices — were allowed to fall immediately after the ideologies that drove their construction passed out of favor. But Brutalism also fell victim to a predictable cycle of fashion: as architecture critics often point out, the public of any era consistently admires hundred-year-old buildings, but condemns (often literally) fifty-year-old buildings. New Yorkers still lament the loss of their grand old Penn Station, but its ornate Beaux-Arts style no doubt looked as heavy-handed and out-of-touch to as many people in the early 1960s, the time of its demolition, as Brutalism does today. What, then, is the case for Brutalist architecture? "It's a sense of place. It's a sense of the drama of the space that they surround," says This Brutal World author Peter Chadwick the BBC clip at the top of the post. "It is sculpture. It's gone beyond being just functional. It's just beautiful sculpture that mirrors its environment." In the DW Euromaxx video below, Deutsches Architekturmuseum curator Oliver Elser sees in Brutalism a valuable lesson for building today: "Make more from less. I think this way of thinking, spatial generosity with simpler materials, is a timely stance for architecture." Architectural historian Elain Harwood calls Brutalism "a particular architecture for ambitious times gripped by a fervor for change. Whatever style you call it, the results are unique and have a heroic beauty than sets them apart from the architecture of any other era." (In fact, some Brutalism enthusiasts who dislike the label have put up the term "Heroic" instead.) Whatever the articulacy of Brutalism's defenders, the most effective arguments for its preservation have been made with not words but images. Chadwick first made his mark with his This Brutal House accounts on Twitter and Instagram, and a search on the latter for the hashtag #brutalism reveals the astonishing range and intensity of the style's 21st-century fandom. A fair few videos have also taken individual works of Brutalism as their subjects, from a reflexively loathed survivor like Boston City Hall to the unlikely upper-middle-class oasis of the Barbican Centre to a high-minded projects now under the wrecking ball like Robin Hood Gardens. Despite how many people seem happy to see Brutalist buildings go, some, like Australian architect Shaun Carter in his TEDx Sydney Salon talk below, remind us of the value of keeping our history concretized, as it were, in the built environment around us. Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloodymindedness: Concrete Poetry writer Jonathan Meades puts it more forcefully: "The destruction of Brutalist buildings is more than the destruction of a particular mode of architecture. It is like burning books. It's a form of censorship of the past, a discomfiting past, by the present. It's the revenge of a mediocre age on an age of epic grandeur." To his mind, it's the destruction of evidence of "a determined optimism that made us more potent than we have become," of the fact that "we don't measure up against those who took risks, who flew and plunged to find new ways of doing things, who were not scared to experiment, who lived lives of perpetual inquiry." If Brutalism has to go, it has to go because it reminds us that "once upon a time, we were not scared to address the Earth in the knowledge that the Earth would not respond, could not respond." Related Content: A is for Architecture: 1960 Documentary on Why We Build, from the Ancient Greeks to Modern Times Watch 50+ Documentaries on Famous Architects & Buildings: Bauhaus, Le Corbusier, Hadid & Many More Bauhaus, Modernism & Other Design Movements Explained by New Animated Video Series 1,300 Photos of Famous Modern American Homes Now Online, Courtesy of USC How Did the Romans Make Concrete That Lasts Longer Than Modern Concrete? The Mystery Finally Solved Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Beauty of Brutalist Architecture: An Introduction in Six Videos is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

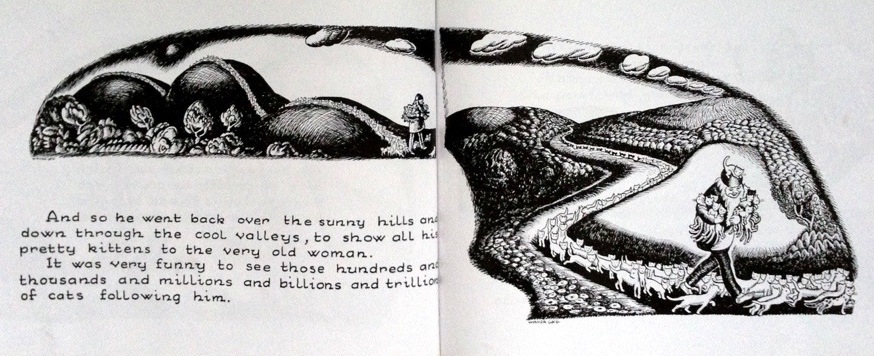

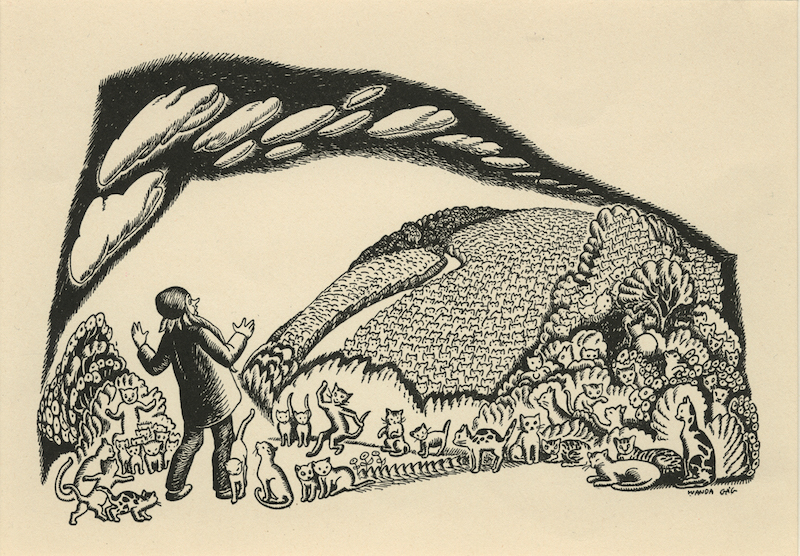

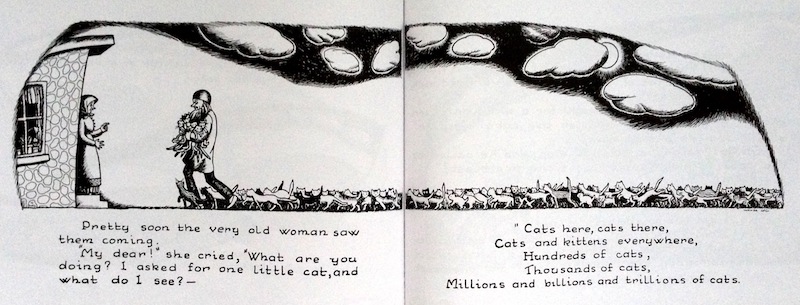

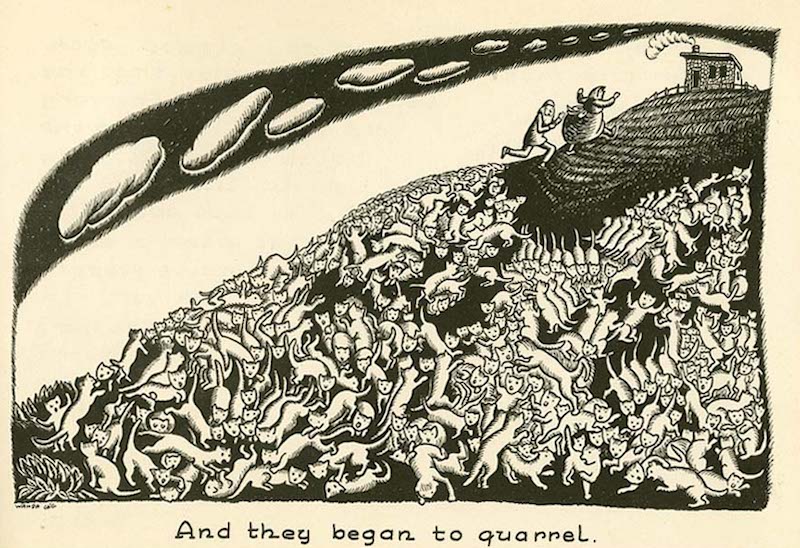

| 4:57p | The First American Picture Book, Wanda Gág’s Millions of Cats (1928)

For better (I’d say), or worse, the internet has turned cat people into what may be the world’s most powerful animal lobby. It has brought us fascinating animated histories of cats and animated stories about the cats of gothic genius and cat-loving author and illustrator Edward Gorey; cats blithely leaving inky pawprints on medieval manuscripts and politely but firmly refusing to be denied entry into a Japanese art museum. It has given us no shortage of delightful photos of artists with their cat familiars… Cat antics and awe have always been a very online phenomenon, but the mysterious and ridiculous, diminutive beasts of prey have also always been inseparable from art and culture. As further evidence, we bring you Millions of Cats, likely the “first truly American picture book done by an American author/artist,” explains a site devoted to it. “Prior to its publication in 1928, there were only English picture books for the children’s perusal.” The book “sky rocketed Wanda Gág into instant fame and set in stone her reputation as a children’s author and illustrator.”

It set a standard for Caldecott-winning children’s literature for close to a hundred years since its appearance, though the award did not yet exist at the time. The book’s creator was “a fierce idealist and did not believe in altering her own aestheticism just because she was producing work for children. She liked to use stylized human figures, asymmetrical compositions, strong lines and slight spatial distortion.” She also loved cats, as befits an artist of her independent temperament, one shared by the likes of other cat-loving artists like T.S. Eliot and Charles Dickens.

Millions of Cats’ author and illustrator may not share in the fame of so many other artists who took pictures with their cats, but she and her cat Noopy were as photogenic as any other feline/human artistic duo, and she was a peer to the best of them. The book’s editor, Ernestine Evans, wrote in the Nation that Millions of Cats “is as important as the librarians say it is. Not only does it bring to book-making one of the most talented and original of American lithographers… but it is a marriage of picture and tale that is perfectly balanced.” Gág (rhymes with “jog”) was “a celebrated artist… in the Greenwich Village-centic Modernist art scene in the 1920s,” writes Lithub, “a free-thinking, sex-positive leftist who also designed her own clothes and translated fairy tales.” She adapted the text from “a story she had made up to entertain her friends’ children,” with the millions of cats modeled on Noopy. Gág is the founding mother of children’s book dynasties like The Cat in the Hat and Pete the Cat, an artist whom millions of cat lovers can discover again or for the first time in a Newbery-winning 2006 collector’s edition. Read a summary of the charming story of Millions of Cats at Lithub and learn more about her, the talented Gág family of artists, and her charming, very cat-friendly house here.

Related Content: Insanely Cute Cat Commercials from Studio Ghibli, Hayao Miyazaki’s Legendary Animation Shop Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online A Digital Archive of 1,800+ Children’s Books from UCLA Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The First American Picture Book, Wanda Gág’s Millions of Cats (1928) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

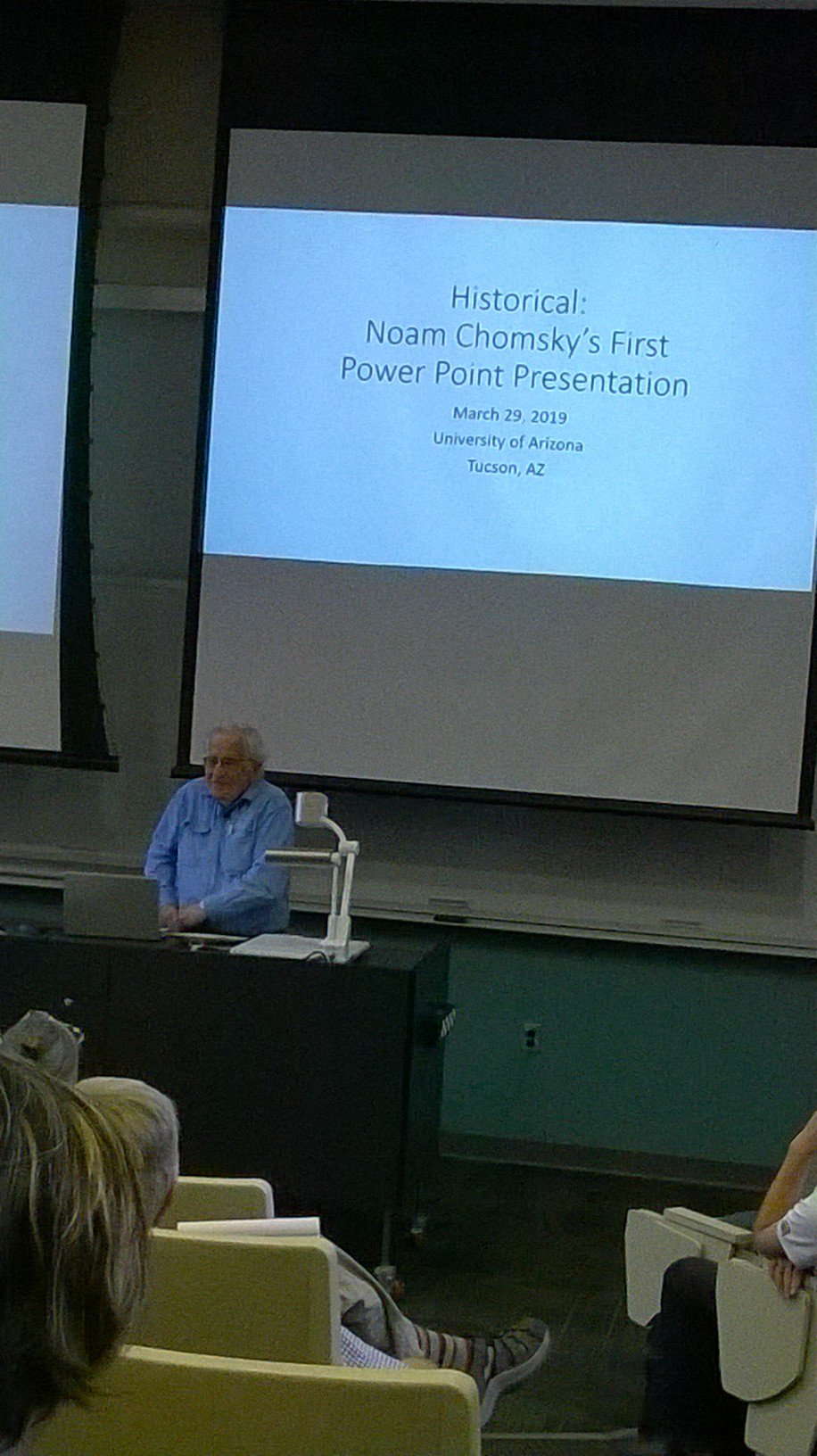

| 7:00p | Noam Chomsky Makes His First Power Point Presentation

90 years old, and still going strong... Related Content: The Ideas of Noam Chomsky: An Introduction to His Theories on Language & Knowledge (1977) Noam Chomsky Defines What It Means to Be a Truly Educated Person Noam Chomsky Makes His First Power Point Presentation is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/04/02 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |