[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, April 16th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 10:37a | How Leonardo da Vinci Drew an Accurate Satellite Map of an Italian City (1502) When I look at maps from centuries ago, I wonder how they could have been of any use. Not only were they filled with mythological monsters and mythological places, but the perspectives mostly served an aesthetic design rather than a practical one. Of course, accuracy was hard to come by without the many mapping tools we take for granted—some of them just in their infancy during the Renaissance, and many more that would have seemed like outlandish magic to nearly everyone in 15th century Europe. Everyone, it sometimes seems, but Leonardo da Vinci, who anticipated and sometimes steered the direction of futuristic public works technology. None of his flying machines worked, and he could hardly have seen images taken from outer space. But he clearly saw the problem with contemporary maps. The necessity of fixing them led to a 1502 aerial image of Imola, Italy, drawn almost as accurately as if he had been peering at the city through a Google satellite camera. “Leonardo,” says the narrator of the Vox video above, “needed to show Imola as an ichnographic map,” a term coined by ancient Roman engineer Vitruvius to describe ground plan-style cartography. No streets or buildings are obscured, as they are in the maps drawn from the oblique perspective of a hilltop or mountain. Leonardo undertook the project while employed as Cesare Borgia’s military engineer. “He was charged with helping Borgia become more aware of the town’s layout.” For this visual aid turned cartographic marvel, he drew from the same source that inspired the elegant Vitruvian Man.

While the visionary Roman builder could imagine a god's eye view, it took someone with Leonardo’s extraordinary perspicacity and skill to actually draw one, in a startlingly accurate way. Did he do it with grit and moxie? Did he astral project thousands of miles above the city? Was he in contact with ancient aliens? No, he used geometry, and a compass, the same means and instruments that allowed ancient scientists like Eratosthenes to calculate the circumference of the earth, to within 200 miles, over 2000 years ago. Leonardo probably also used an instrument called a bussola, a device that measures degrees inside a circle—like the one that surrounds his city map. Painstakingly recording the angles of each turn and intersection in the town and measuring their distance from each other would have given him the data he needed to recreate the city as seen from above, using the bussola to maintain proper scale. Other methods would have been involved, all of them commonly available to surveyors, builders, city planners, and cartographers at the time. Leonardo trusted the math, even though he could never verify it, but like the best mapmakers, he also wanted to make something beautiful. It may be difficult for historians to determine which inaccuracies are due to miscalculation and which to deliberate distortion for some artistic purpose. But license or mistakes aside, Leonardo’s map remains an astonishing feat, marking a seismic shift from the geography of “myth and perception” to one of “information, drawn plainly.” There’s no telling if the archetypal Renaissance man would have liked where this path led, but if he lived in the 21st century, he'd already have his mind trained on ideas that anticipate technology hundreds of years in our future. Related Content: Leonardo da Vinci Saw the World Differently… Thanks to an Eye Disorder, Says a New Scientific Study Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Leonardo da Vinci Drew an Accurate Satellite Map of an Italian City (1502) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:19p | “Kubrick/Tarkovsky”: A Video Essay Explores the Visual Similarities Between the Two “Cinematic Giants” Who are your favorite filmmakers? Responses to that question including the names Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky have been heard so often, for so long, that they've passed into the realm of cinephile cliché. How, then, to rediscover what about their films makes Kubrick and Tarkovsky synonymous with the very concept of the brilliant auteur? In "Kubrick/Tarkovsky" above, cinematic video essayist Vugar Efendi sheds light on the essence of these two "cinematic giants" by putting their work side by side: Eyes Wide Shut next to Ivan's Childhood, A Clockwork Orange next to Stalker, Paths of Glory next to Andrei Rublev. (You may remember a similar comparison, previously featured here on Open Culture, between Kubrick and Wes Anderson.) Fortunately, "Kubrick/Tarkovsky" sheds only four and a half minutes of light, prolonged exposure to so many masterworks at once potentially being too much for many cinephiles to bear. For directors with such strong visions of their own, it might also come as a surprise to see such strong resonances between their images, such as Jack's walk into the Overlook Hotel's suddenly populated (and returned to the Jazz Age) ballroom from The Shining alongside Domenico's candle-bearing walk across the empty pool with a candle from Nostalghia and 2001: A Space Odyssey's journey through the "star gate" alongside Solaris' drive through Tokyo-as-humanity's-urban-future. Kubrick appreciated Solaris enough for it to make a list of 93 films he really liked, but Tarkovsky didn't feel the same way about 2001. "A detailed ‘examination’ of the technological processes of the future transforms the emotional foundation of a film, as a work of art, into a lifeless schema with only pretensions to truth," he said in an interview before he made Solaris, describing what he would get right that Kubrick had got wrong. From just the brief clips of those pictures included in "Kubrick/Tarkovsky," even viewers who have never seen either director's films can tell how differently they realized their visions of humanity's space-voyaging future. Throughout the rest of the essay as well, each emphasis on a visual similarity comes with an emphasis on deeper difference; as one of the video's commenters astutely puts it, "Tarkovsky is dreams, Kubrick is nightmares." Related Content: Discover the Life & Work of Stanley Kubrick in a Sweeping Three-Hour Video Essay How Stanley Kubrick Made His Masterpieces: An Introduction to His Obsessive Approach to Filmmaking Signature Shots from the Films of Stanley Kubrick: One-Point Perspective “Auteur in Space”: A Video Essay on How Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris Transcends Science Fiction Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris Shot by Shot: A 22-Minute Breakdown of the Director’s Filmmaking A Poet in Cinema: Andrei Tarkovsky Reveals the Director’s Deep Thoughts on Filmmaking and Life Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. “Kubrick/Tarkovsky”: A Video Essay Explores the Visual Similarities Between the Two “Cinematic Giants” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

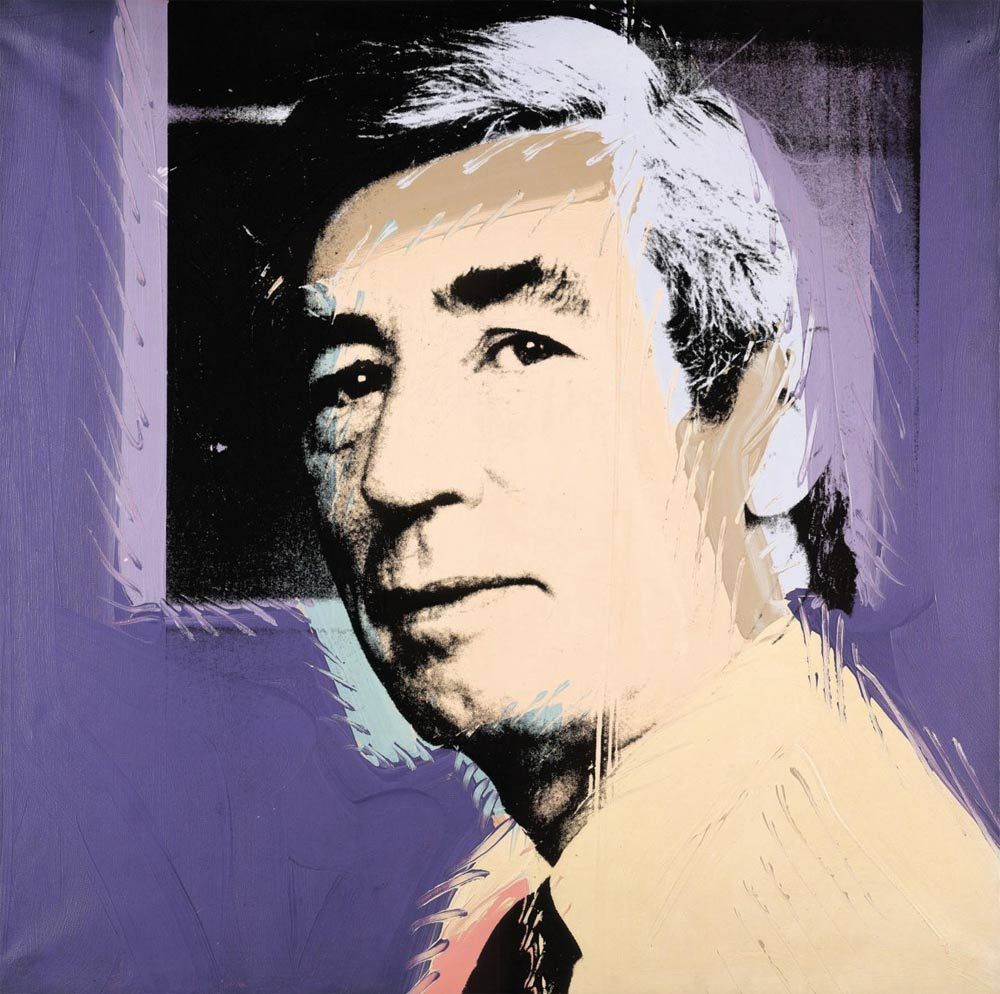

| 5:00p | How Andy Warhol and Tintin Creator Hergé Mutually Admired and Influenced One Another

Comic-book stories of a boy reporter and his dog (later accompanied by a foulmouthed sea captain) featuring rocketships and submarines, booby-traps and buried treasure, gangsters and abominable snowmen, smugglers and super-weapons, all told with bright colors, clear lines, and practically no girls in sight: no wonder The Adventures of Tintin at first looks tailor-made for rambunctious youngsters. But now, eighty years after Tintin's debut in the children's supplement of a Belgian Catholic newspaper, his ever-growing fan base surely includes more grown-ups than it does kids, and grown-ups prepared to regard his adventures as serious works of modern art at that. The field of Tintin enthusiasts (in their most dedicated form, "Tintinologists") includes some of the best-known modern artists in history. Roy Lichtenstein, he of the zoomed-in comic-book aesthetic, once made Tintin his subject, and Tintin's creator Hergé, who cultivated a love for modern art from the 1960s onward, hung a suite of Lichtenstein prints in his office. As Andy Warhol once put it, "Hergé has influenced my work in the same way as Walt Disney. For me, Hergé was more than a comic strip artist." And for Hergé, Warhol seems to have been more than a fashionable American painter: in 1979, Hergé commissioned Warhol to paint his portrait, and Warhol came up with a series of four images in a style reminiscent of the one he'd used to paint Jackie Onassis and Marilyn Monroe. Hergé and Warhol had first met in 1972, when Hergé paid a visit to Warhol's "Factory" in New York — the kind of setting in which one imagines the straight-laced, sixtysomething Belgian setting foot only with difficulty. But the two had more in common as artists than it may seem: both got their start in commercial illustration, and both soon found their careers defined by particular works that exploded into cultural phenomena. (Warhol may also have felt an affinity with Tintin in their shared recognizability by hairstyle alone.) The Independent's John Lichfield writes that Hergé, who had by that point learned to paint a few modern abstract pieces of his own, "asked Warhol, modestly, whether the father of Tintin should also consider himself a 'Pop Artist.' Warhol, although a great fan of Hergé, simply stared back at him and did not reply."

Warhol may not have known what to say forty years ago, but in that time Hergé has unquestionably ascended into the institutional pantheon of Western art: Lichfield's article is a review of a 2006 Hergé retrospective at the Pompidou Centre, and the years since have seen the opening of the Musée Hergé south of Brussels as well as increasingly elaborate exhibitions on Tintin and his creator all around the world. (I myself attended such an exhibition in Seoul, where I live, just last month.) The French artist Jean-Pierre Raynaud expresses a now-common kind of sentiment when he credits Hergé with "a precision of the kind I love in Mondrian" and "the artistic economy that you find in Matisse." Warhol, who probably wouldn't have phrased his appreciation in quite that way, makes a more tonally characteristic response in the clip above when Hergé tells him about Tintin's latter-day switch from his signature plus fours to jeans: "Oh, great!" Related Content: Hergé Draws Tintin in Vintage Footage (and What Explains the Character’s Enduring Appeal) When Steve Jobs Taught Andy Warhol to Make Art on the Very First Macintosh (1984) Andy Warhol Digitally Paints Debbie Harry with the Amiga 1000 Computer (1985) The Odd Couple: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, 1986 Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol Demystify Their Pop Art in Vintage 1966 Film Comics Inspired by Waiting For Godot, Featuring Tintin, Roz Chast, and Beavis & Butthead Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. How Andy Warhol and Tintin Creator Hergé Mutually Admired and Influenced One Another is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:53p | A Virtual Time-Lapse Recreation of the Building of Notre Dame (1160) Hundreds of gothic cathedrals dotted all over Europe have faced decimation and destruction, whether through sackings, revolutions, natural decay, or bombing raids. But since World War II, at least, the most extraordinary examples that remain have seen restoration and constant upkeep, and none of them is as well-known and as culturally and architecturally significant as Paris’s Notre Dame. One cannot imagine the city without it, which made the scenes of Parisians watching the cathedral burn yesterday as poignant as the scenes of the fire itself. The flames claimed the rib-vaulted roof and the “spine-tingling, soul-lifting spire,” writes The Washington Post, who quote cathedral spokeman Andre Finot’s assessment of the damage as “colossal.” The exterior stone towers, famed stained-glass windows, and iconic arches and flying buttresses withstood the disaster, but the wooden interior, “a marvel,” writes the Post, “that has inspired awe and wonder for the millions who have visited over the centuries—has been gutted.” Nothing of the frame, says Finot, “will remain." The sad irony is that the fire reportedly resulted from an accident during the medieval church’s renovation, one of many such projects that have preserved this almost 900-year-old architecture. The French government has vowed to rebuild. Will it matter to posterity that a significant portion of the Cathedral dates from hundreds of years after its original construction? Will Notre Dame lose its ancient aura, and what does this mean for Parisians and the world? It’s too soon to answer questions like these and too soon to ask them. Now is a time to reckon with cultural and historical loss, and to appreciate the importance of what was saved. At the top of the post, you can watch a virtual time-lapse recreation of the construction of Notre Dame, begun in 1160 and mostly completed one hundred years later, though building continued into the 14th century—a jaw-dropping time scale in an era when towering new buildings go up in a matter of weeks. After taking more than the human lifespan to complete, until yesterday the cathedral stood the test of time, as the brief France in Focus tour of its eight centuries of art and architectural history above explains. “The most visited monument in the French Capital” may be a relic of a very different, pre-modern, pre-revolutionary, France. But its imposing central setting in the city, and in modern works from Victor Hugo’s Hunchback of Notre Dame to Walt Disney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame—not to mention the tourists, religious pilgrims, scholars, and art students who pour into Paris to see it—mark Notre Dame as a very contemporary landmark. Learn more about how it became so above. Related Content: Notre Dame Captured in an Early Photograph, 1838 The History of Western Architecture: From Ancient Greece to Rococo (A Free Online Course) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness A Virtual Time-Lapse Recreation of the Building of Notre Dame (1160) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/04/16 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |