[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, May 7th, 2019

- “State the idea you wish to express as clearly as possible, and in terms preschoolers can understand.” Example: It is dangerous to play in the street.

- “Rephrase in a positive manner,” as in It is good to play where it is safe.

- “Rephrase the idea, bearing in mind that preschoolers cannot yet make subtle distinctions and need to be redirected to authorities they trust.” As in, “Ask your parents where it is safe to play.”

- “Rephrase your idea to eliminate all elements that could be considered prescriptive, directive, or instructive.” In the example, that’d mean getting rid of “ask”: Your parents will tell you where it is safe to play.

- “Rephrase any element that suggests certainty.” That’d be “will”: Your parents can tell you where it is safe to play.

- “Rephrase your idea to eliminate any element that may not apply to all children.” Not all children know their parents, so: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play.

- “Add a simple motivational idea that gives preschoolers a reason to follow your advice.” Perhaps: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. It is good to listen to them.

- “Rephrase your new statement, repeating the first step.” “Good” represents a value judgment, so: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. It is important to try to listen to them.

- “Rephrase your idea a ?nal time, relating it to some phase of development a preschooler can understand.” Maybe: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. It is important to try to listen to them, and listening is an important part of growing.

| Time | Event |

| 2:00p | Pioneering Computer Scientist Grace Hopper Shows Us How to Visualize a Nanosecond (1983) Human imagination seems seriously limited when faced with the cosmic scope of time and space. We can imagine, through stop-motion animation and CGI, what it might be like to walk the earth with creatures the size of office buildings. But how to wrap our heads around the fact that they lived hundreds of millions of years ago, on a planet some four and a half billion years old? We trust the science, but can’t rely on intuition alone to guide us to such mind-boggling knowledge. At the other end of the scale, events measured in nanoseconds, or billionths of a second, seem inconceivable, even to someone as smart as Grace Hopper, the Navy mathematician who invented COBOL and helped built the first computer. Or so she says in the 1983 video clip above from one of her many lectures in her role as a guest lecturer at universities, museums, military bodies, and corporations. When she first heard of “circuits that acted in nanoseconds,” she says, “billionths of a second… Well, I didn’t know what a billion was…. And if you don’t know what a billion is, how on earth do you know what a billionth is? Finally, one morning in total desperation, I called over the engineering building, and I said, ‘Please cut off a nanosecond and send it to me.” What she asked for, she explains, and shows the class, was a piece of wire representing the distance a signal could travel in a nanosecond.

Follow the rest of her explanation, with wire props, and see if you can better understand a measure of time beyond the reaches of conscious experience. The explanation was immediately successful when she began using it in the late 1960s “to demonstrate how designing smaller components would produce faster computers,” writes the National Museum of American History. The bundle of wires below, each about 30cm (11.8 inches) long, comes from a lecture Hopper gave museum docents in March 1985.

Photo via the National Museum of American History Like the age of the dinosaurs, the nanosecond may only represent a small fraction of the incomprehensibly small units of time scientists are eventually able to measure—and computer scientists able to access. “Later,” notes the NMAH, “as components shrank and computer speeds increased, Hopper used grains of pepper to represent the distance electricity traveled in a picosecond, one trillionth of a second.” At this point, the map becomes no more revealing than the unknown territory, invisible to the naked eye, inconceivable but through wild leaps of imagination. But if anyone could explain the increasingly inexplicable in terms most anyone could understand, it was the brilliant but down-to-earth Hopper. via Kottke Related Content: Free Online Computer Science Courses Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Pioneering Computer Scientist Grace Hopper Shows Us How to Visualize a Nanosecond (1983) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 4:18p | Why the World’s Best Mathematicians Are Hoarding Japanese Chalk Here's the latest from Great Big Story: "Once upon a time, not long ago, the math world fell in love ... with a chalk. But not just any chalk! This was Hagoromo: a Japanese brand so smooth, so perfect that some wondered if it was made from the tears of angels. Pencils down, please, as we tell the tale of a writing implement so irreplaceable, professors stockpiled it." Head over to Amazon and try to buy it, and all you get is: "Currently unavailable. We don't know when or if this item will be back in stock." Indeed, they've stockpiled it all. Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. Related Content: Stephen Hawking’s Lectures on Black Holes Now Fully Animated with Chalkboard Illustrations The Map of Mathematics: Animation Shows How All the Different Fields in Math Fit Together Why the World’s Best Mathematicians Are Hoarding Japanese Chalk is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

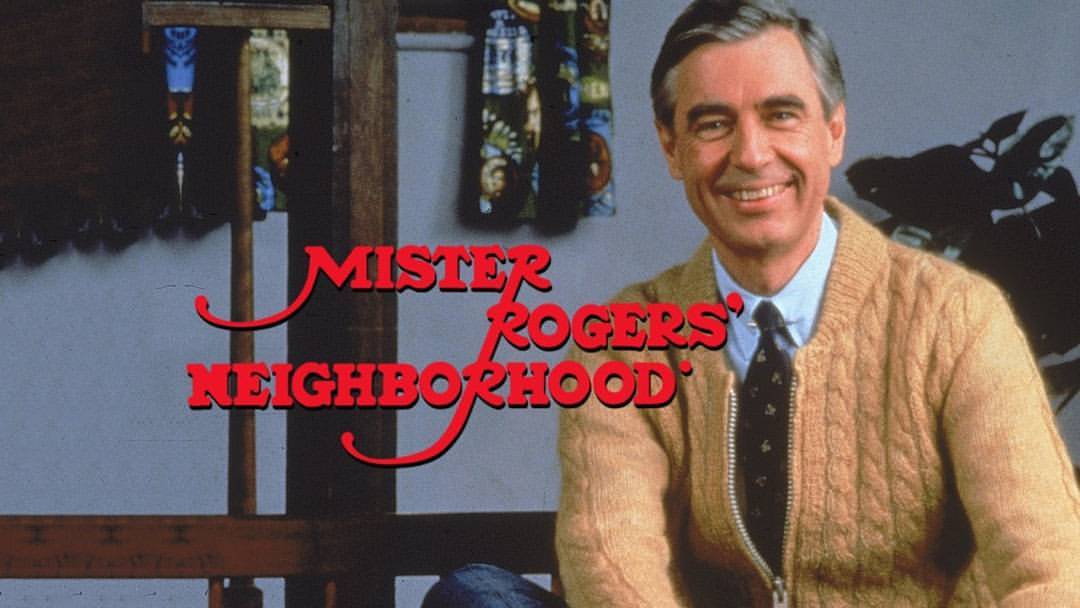

| 6:00p | Mr. Rogers’ Nine Rules for Speaking to Children (1977)

The maxim “children need rules” does not necessarily describe either a right-wing position or a leftist one; either a political or a religious idea. Ideally, it points to observable facts about the biology of developing brains and psychology of developing personalities. It means creating structures that respect kids’ intellectual capacities and support their physical and emotional growth. Substituting "structure" for rules suggests even more strongly that the “rules” are mainly requirements for adults, those who build and maintain the world in which kids live. Grown-ups must, to the best of their abilities, try and understand what children need at their stage of development, and try to meet those needs. When Susan Sontag’s son David was 7 years old, for example, the writer and filmmaker made a list of ten rules for herself to follow, touching on concerns about his self-concept, relationship with his father, individual preferences, and need for routine. Her first rule serves as a general heading for the prescriptions in the other nine: “Be consistent.” Sontag’s rules only emerged from her journals after her death. She did not turn them into public parenting tips. But nearly ten years after she wrote them, a man appeared on television who seemed to embody their exactitude and simplicity. From the very beginning in 1968, Fred Rogers insisted that his show be built on strict rules. “There were no accidents on Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood,” says former producer Arthur Greenwald. Or as Maxwell King, author of a recent biography on Rogers, writes at The Atlantic:

In addition to his consistency, almost to the point of self-parody, Rogers made sure to always be absolutely crystal clear in his speech. He understood that young kids do not understand metaphors, mostly because they haven’t learned the commonly agreed-upon meanings. Preschool-age children also have trouble understanding the same uses of words in different contexts. In one segment on the show, for example, a nurse says to a child wearing a blood-pressure cuff, “I’m going to blow this up.” Rogers had the crew redub the line with “’I’m going to puff this up with some air.’ ’Blow up’ might sound like there’s an explosion,” Greenwald remembers, “and he didn’t want kids to cover their ears and miss what would happen next.” In another example, Rogers wrote a song called “You Can Never Go Down the Drain,” to assuage a common fear that very young children have. There is a certain logic to the thinking. Drains take things away, why not them? Rogers “was extraordinarily good at imagining where children’s minds might go,” writes King, explaining to them, for example, that an ophthalmologist could not look into his mind and see his thoughts. His care with language so amused and awed the show’s creative team that in 1977, Greenwald and writer Barry Head created an illustrated satirical manual called “Let’s Talk About Freddish.” Anyone who’s seen the documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? knows Rogers could take a good-natured joke at his expense, likely including the imaginative reconstruction of his methods below. His crew respected him so much that even their parodies serve as slightly exaggerated tributes to his concerns. Rogers adapted his philosophical guidelines from the top psychologists and child-development experts of the time. The 9 Rules (or maybe 9 Stages) of “Freddish” above, as imagined by Greenwald and Head, reflect their work. Maybe implied in the joke is that his meticulous procedure, considering the possible effects of every word, would be impossible to emulate outside of his scripted encounters with children, prepped for by hours of conversation with child-development specialist Margaret McFarland. Such is the kind of experience parents, teachers, and other caretakers never have. But Rogers understood and acknowledged the unique power and privilege of his role, more so than most every other children’s TV programmer. He made sure to get it right, as best he could, each time, not only so that kids could better take in the information, but so the grown-ups in their lives could make themselves better understood. Rogers wanted us to know, says Greenwald, "that the inner life of children was deadly serious to them," and thus deserving of care and recognition. via Mental Floss Related Content: Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Mr. Rogers’ Nine Rules for Speaking to Children (1977) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:00p | How David Bowie Used William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up Method to Write His Unforgettable Lyrics Why do David Bowie's songs sounds like no one else's, right down to the words that turn up in their lyrics? Novelist Rick Moody, who has been privy more than once to details of Bowie's songwriting process, wrote about it in his column on Bowie's 2013 album The Next Day: "David Bowie misdirects autobiographical interpretation, often, by laying claim to reportage and fiction as songwriting methodologies, and he cloaks himself, further, in the cut-up." Anyone acquainted with the work of William S. Burroughs will recognize that term, which refers to the process of literally cutting up existing texts in order to generate new meanings with their rearranged pieces. You can see how Bowie performed his cut-up composition in the 1970s in the clip above, in which he demonstrates and explains his version of the method. "What I've used it for, more than anything else, is igniting anything that might be in my imagination," he says. "It can often come up with very interesting attitudes to look into. I tried doing it with diaries and things, and I was finding out amazing things about me and what I'd done and where I was going." Given what he sees as its ability to shed light on both the future and the past, he describes the cut-up method as "a very Western tarot" — and one that can provide just the right unexpected combination of sentences, phrases, or words to inspire a song. As dramatically as Bowie's self-presentation and musical style would change over the subsequent decades, the cut-up method would only become more fruitful for him. When Moody interviewed Bowie in 1995, Bowie "observed that he worked somewhere near to half the time as a lyricist in the cut-up tradition, and he even had, in those days, a computer program that would eat the words and spit them back in some less referential form." Bowie describes how he uses that computer program in the 1997 BBC clip above: "I'll take articles out of newspapers, poems that I've written, pieces of other people's books, and put them all into this little warehouse, this container of information, and then hit the random button and it will randomize everything." Amid that randomness, Bowie says, "if you put three or four dissociated ideas together and create awkward relationships with them, the unconscious intelligence that comes from those pairings is really quite startling sometimes, quite provocative." Sixteen years later, Moody received a startling and provocative set of seemingly dissociated words in response to a long-shot e-mail he sent to Bowie in search of a deeper understanding of The Next Day. It ran as follows, with no further comment from the artist: Effigies Indulgences Anarchist Violence Chthonic Intimidation Vampyric Pantheon Succubus Hostage Transference Identity Mauer Interface Flitting Isolation Revenge Osmosis Crusade Tyrant Domination Indifference Miasma Pressgang Displaced Flight Resettlement Funereal Glide Trace Balkan Burial Reverse Manipulate Origin Text Traitor Urban Comeuppance Tragic Nerve Mystification "Chthonic is a great word," Moody writes, "and all art that is chthonic is excellent art." He adds that "when Bowie says chthonic, it’s obvious he’s not just aspiring to chthonic, the album has death in nearly every song" — a theme that would wax on Bowie's next and final album, though The Next Day came after an emergency heart surgery ended his live-performance career. "Chthonic has personal heft behind it, as does isolation, which is a word a lot like Isolar, the name of David Bowie’s management enterprise." Moody scrutinizes each and every one of the words on the list in his column, finding meanings in them that, whatever their involvement in the creation of the album, very much enrich its listening experience. By using techniques like the cut-up method, Bowie ensured that his songs can never truly be interpreted — not that it will keep generation after generation of intrigued listeners from trying. Related Content: How to Jumpstart Your Creative Process with William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up Technique How David Bowie, Kurt Cobain & Thom Yorke Write Songs With William Burroughs’ Cut-Up Technique How William S. Burroughs Used the Cut-Up Technique to Shut Down London’s First Espresso Bar (1972) How Leonard Cohen & David Bowie Faced Death Through Their Art: A Look at Their Final Albums Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. How David Bowie Used William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up Method to Write His Unforgettable Lyrics is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/05/07 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |