[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, May 8th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 2:00p | What the Theory?: Watch Short Introductions to Postmodernism, Semiotics, Phenomenology, Marxist Literary Criticism and More Theory. The word alone can intimidate, and it can especially intimidate those of us outside the academic humanities. The rigor and complexity of scientific theory is forbidding enough, but cultural theory, with its thickets of multivalent meaning and thinkers with their cultishly devoted and territorial followings, has surely made many a hopeful learner turn back before they've even stepped in. But help has arrived in this age of explainers, most recently in the form of a University of Exeter PhD student and Youtuber named Tom Nicholas who has taken it upon himself to explain such tricky subjects as postmodernism, semiotics, phenomenology, and many others besides in his series "What the Theory?" Nicolas has put his academic background into videos on everything from how to read journal articles and write essays to subjects like his own research and how Bojack Horseman critiques the 1990s. But it's "What the Theory?" that most directly confronts the intellectual frameworks that his other videos put to more implicit use. In it he breaks down the nature of the most abstruse-sounding disciplines in all the modern humanities as well as the ideas of the theorists who developed them — semiotics and Ferdinand de Saussure, phenomenology and Martin Heidegger, cultural materialism and Raymond Williams, as well as broader concepts like postmodernism and even the modernism that preceded it — illuminating them by drawing upon a set of less-rarefied works, including but not limited to Dunkirk and The Lego Movie. In more recent "What the Theory?" videos, Nicholas takes on individual ideas as popularized (at least within the academy) by certain writers, theorists, and philosophers. He explains, for example, what Roland Barthes meant when he proclaimed "the death of the author" in 1967, as well as what Barthes' countryman Guy Debord meant when he described humanity as living in a "society of the spectacle" that same year. Watch through the entire "What the Theory?" playlist so far, and there's a chance you might come away with an interest in launching an academic career of your own in order to dig deeper into these and other ideas. But there's a much greater chance that you'll come away believing that these critical texts actually do have insights to offer our world, the societies that make up our world, and the culture that drives those societies — barely intelligible though many of them may still look. Related Content: A Quick Introduction to Literary Theory: Watch Animated Videos from the Open University Yale Presents a Free Online Course on Literary Theory, Covering Structuralism, Deconstruction & More David Foster Wallace on What’s Wrong with Postmodernism: A Video Essay Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. What the Theory?: Watch Short Introductions to Postmodernism, Semiotics, Phenomenology, Marxist Literary Criticism and More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:38p | Is the Leonardo da Vinci Painting “Salvator Mundi” (Which Sold for $450 Million in 2017) Actually Authentic?: Michael Lewis Explores the Question in His New Podcast

Journalist and bestselling author Michael Lewis (Liar's Poker, Moneyball, The Big Short) has a new podcast, Against the Rules, that "takes a searing look at what’s happened to fairness—in financial markets, newsrooms, basketball games, courts of law, and much more. And he asks what’s happening to a world where everyone loves to hate the referee." That is, what happens when we, as a society, lose confidence in the arbiters of truth and fairness? In Episode 5, Lewis focuses on “Salvator Mundi,” a painting of Jesus Christ attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, which famously sold at auction for $450 million in 2017. Pretty remarkable, considering that some question whether “Salvator Mundi,” is really a Leonardo painting at all. Or, if it is, whether the highly-restored painting still retains any brushstrokes from Leonardo himself. This leads Lewis to ask some intriguing questions about the authenticity of art, and to explore the pressure placed on the referees of art--namely, art historians--to confirm the authenticity of potentially valuable paintings. Below, you can stream the episode, "The Hand of Leonardo." As a bonus, we've also added an episode that examines how sketchy "customer service" companies mislead people trying to repay their student loans, and how the Trump administration has undermined government agencies designed to protect debt-strapped Americans. Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. Is the Leonardo da Vinci Painting “Salvator Mundi” (Which Sold for $450 Million in 2017) Actually Authentic?: Michael Lewis Explores the Question in His New Podcast is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

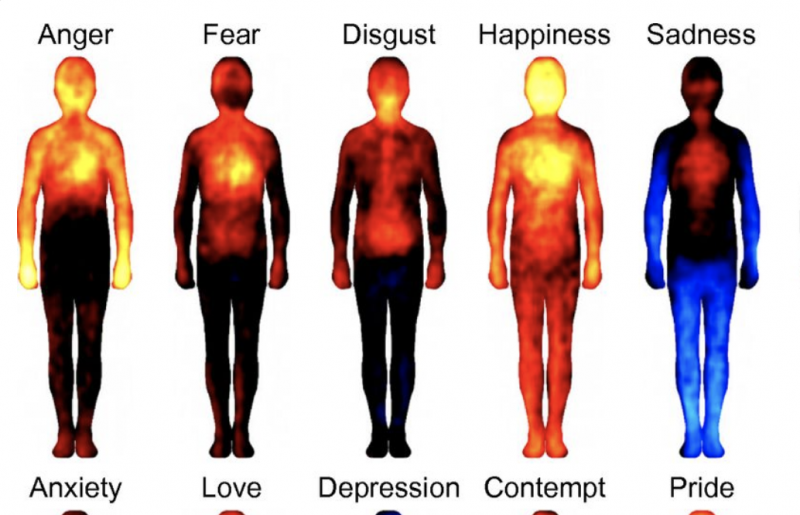

| 7:45p | Mapping Emotions in the Body: A Finnish Neuroscience Study Reveals Where We Feel Emotions in Our Bodies “Eastern medicine” and “Western medicine”—the distinction is a crude one, often used to misinform, mislead, or grind cultural axes rather than make substantive claims about different theories of the human organism. Thankfully, the medical establishment has largely given up demonizing or ignoring yogic and meditative mind-body practices, incorporating many of them into contemporary pain relief, mental health care, and preventative and rehabilitative treatments. Hindu and Buddhist critics may find much not to like in the secular appropriation of practices like mindfulness and yoga, and they may find it odd that such a fundamental insight as the relationship between mind and body should ever have been in doubt. But we know from even a slight familiarity with European philosophy (“I think, therefore I am”) that it was from the Enlightenment into the 20th century. Now, says Riitta Hari, co-author of a 2014 Finish study on the bodily locations of emotion, “We have obtained solid evidence that shows the body is involved in all types of cognitive and emotional functions. In other words, the human mind is strongly embodied.” We are not brains in vats. All those colorful old expressions—“cold feet,” “butterflies in the stomach,” “chill up my spine”—named qualitative data, just a handful of the embodied emotions mapped by neuroscientist Lauri Nummenmaa and co-authors Riitta Hari, Enrico Glerean, and Jari K. Hietanen.

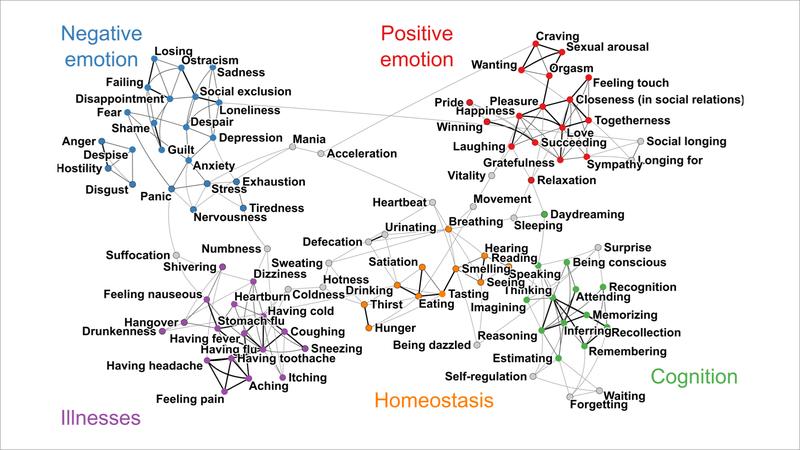

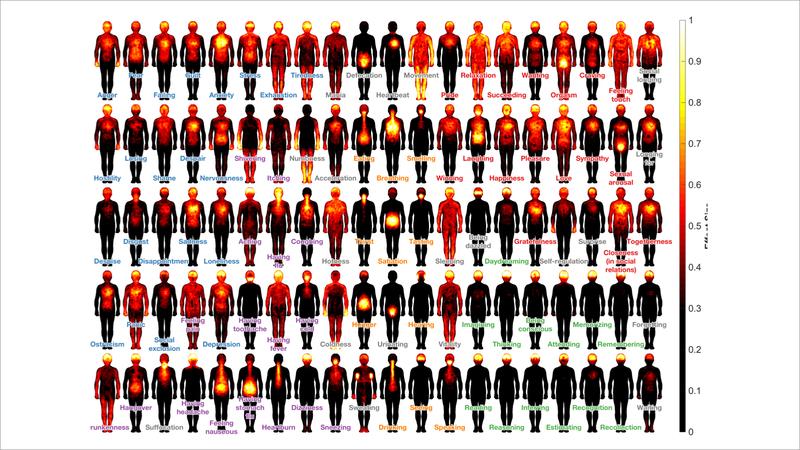

In their study, the researchers “recruited more than 1,000 participants” for three experiments, reports Ashley Hamer at Curiosity. These included having people “rate how much they experience each feeling in their body vs. in their mind, how good each one feels, and how much they can control it.” Participants were also asked to sort their feelings, producing “five clusters: positive feelings, negative feelings, cognitive processes, somatic (or bodily) states and illnesses, and homeostatic states (bodily functions).” After making careful distinctions between not only emotional states, but also between thinking and sensation, the study participants colored blank outlines of the human body on a computer when asked where they felt specific feelings. As the video above from the American Museum of Natural History explains, the researchers “used stories, video, and pictures to provoke emotional responses,” which registered onscreen as warmer or cooler colors.

Similar kinds of emotions clustered in similar places, with anger, fear, and disgust concentrating in the upper body, around the organs and muscles that most react to such feelings. But “others were far more surprising, even if they made sense intuitively,” writes Hamer “The positive emotions of gratefulness and togetherness and the negative emotions of guilt and despair all looked remarkably similar, with feelings mapped primarily in the heart, followed by the head and stomach. Mania and exhaustion, another two opposing emotions, were both felt all over the body.”

The researchers controlled for differences in figurative expressions (i.e. “heartache”) across two languages, Swedish and Finnish. They also make reference to other mind-body theories, such as using “somatosensory feedback... to trigger conscious emotional experiences” and the idea that “we understand others’ emotions by simulating them in our own bodies.” Read the full, and fully illustrated, study results in “Bodily Maps of Emotions,” published by the National Academy of Sciences. Related Content: How Meditation Can Change Your Brain: The Neuroscience of Buddhist Practice Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Mapping Emotions in the Body: A Finnish Neuroscience Study Reveals Where We Feel Emotions in Our Bodies is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

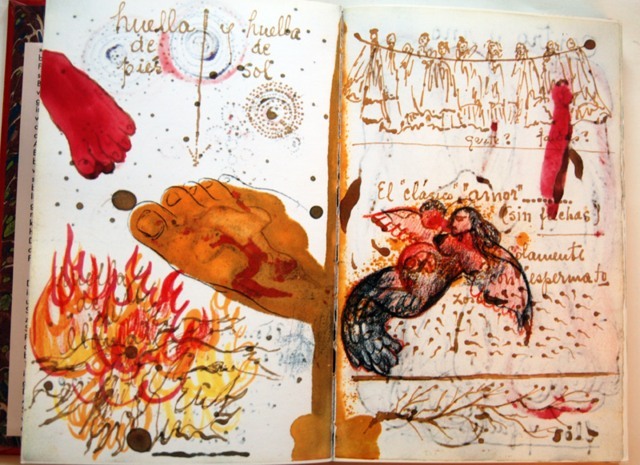

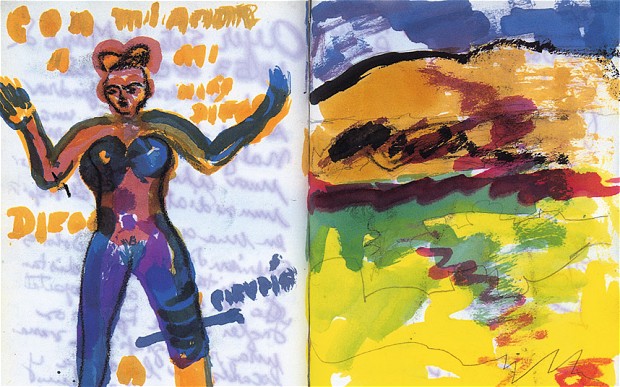

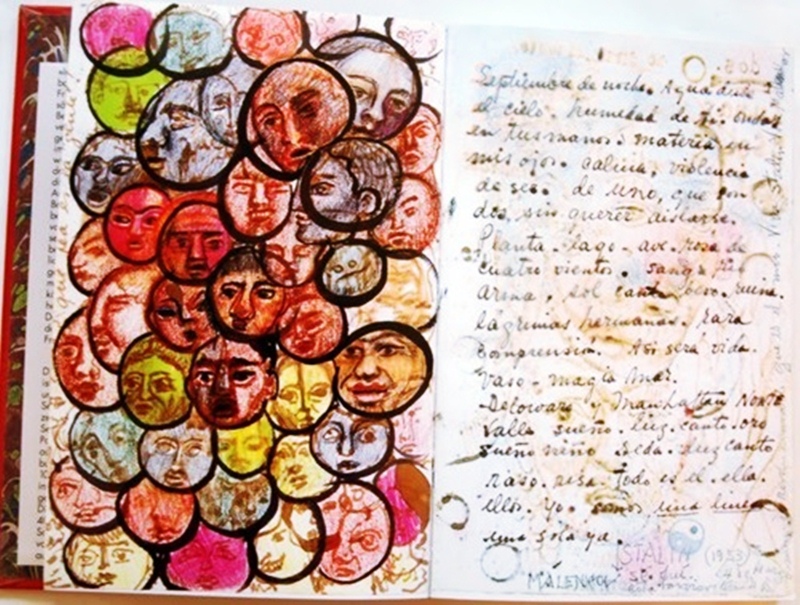

| 8:00p | Discover Frida Kahlo’s Wildly-Illustrated Diary: It Chronicled the Last 10 Years of Her Life, and Then Got Locked Away for Decades

When we admire a famous artist from the past, we may wish to know everything about their lives—their private loves and hates, and the inner worlds to which they gave expression in canvases and sculptures. A biography may not be strictly necessary for the appreciation of an artist’s work. Maybe in some cases, knowing too much about an artist can make us see the autobiographical in everything they do. Frida Kahlo, on the other hand, fully invited such interpretation, and made knowing the facts of her life a necessity.

She can hardly "be accused of having invented her problems," writes Deborah Solomon at The New York Times, yet she invented a new visual vocabulary for them, achieving her mostly posthumous fame “by making her unhappy face the main subject of her work.” Her “specialty was suffering”—her own—“and she adopted it as an artistic theme as confidently as Mondrian claimed the rectangle or Rubens the corpulent nude.” Kahlo treated her life as worthy a subject as the respectable middle-class still lifes and aristocratic portraits of the old masters. She transfigured herself into a personal language of symbols and surreal motifs.

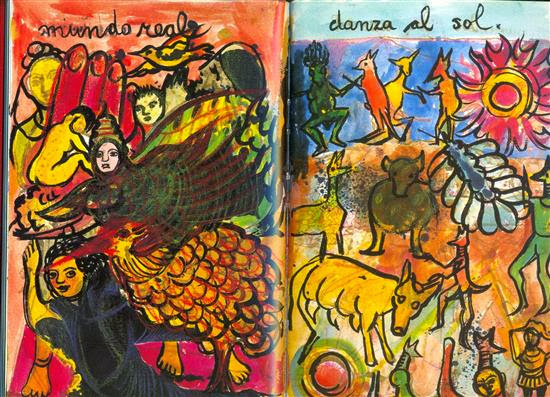

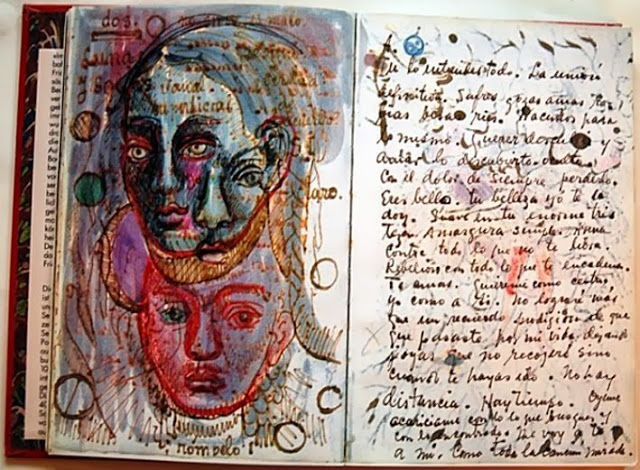

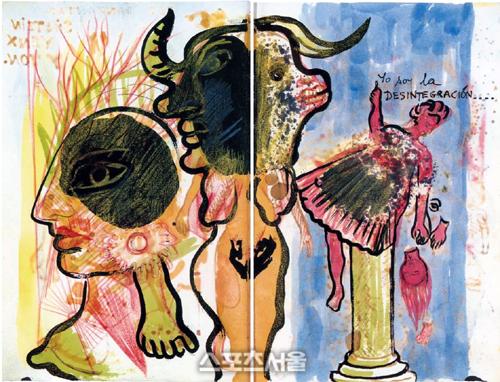

This means we must peer as closely into Kahlo’s life as we are able if we want to fully enter into what Museum of Modern Art curator Kirk Varnedoe called “her construction of a theater of the self.” But we may not feel much closer to her after reading her wildly-illustrated diary, which she kept for the last ten years of her life, and which was locked away after her death in 1954 and only published forty years later, with an introduction by Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes. The diary was then republished by Abrams in a beautiful hardcover edition that retains Fuentes’ introduction.

If you’re looking for a historical chronology or straightforward narrative, prepare for disappointment. It is, writes Kathryn Hughes at The Telegraph, a diary “of a very particular kind. There are few dates in it, and it has nothing to say about events in the external world—Communist Party meetings, appointments at the doctor’s or even trysts with Diego Rivera, the artist whom Kahlo loved so much that she married him twice. Instead it is full of paintings and drawings that appear to be dredged from her fertile unconscious.”

This descriptions suggests that the diary substitutes the image for the word, but this is not so—it is filled with Kahlo’s experiments with language: playful prose-poems, witty and cryptic captions, free-associative happy accidents. Like the visual autobiography of kindred spirit Jean-Michel Basquiat, her private feelings must be inferred from documents in which image and word are inseparable. There are “neither startling disclosures,” writes Solomon, “nor the sort of mundane, kitchen-sink detail that captivates by virtue of its ordinariness.” Rather than exposition, the diary is filled, as Abrams describes it, with "thoughts, poems, and dreams... along with 70 mesmerizing watercolor illustrations."

Kahlo’s diary allows for no “dreamy identification with its subject” notes Solomon, through Instagram-worthy summaries of her dinners or wardrobe woes. Unlike her many, gushing letters to Rivera and other lovers, the “irony is that these personal sketches are surprisingly impersonal.” Or rather, they express the personal in her preferred private language, one we must learn to read if we want to understand her work. More than any other artist of the time, she turned biography into mythology.

Knowing the bare facts of her life gives us much-needed context for her images, but ultimately we must deal with them on their own terms as well. Rather than explaining her painting to us, Kahlo’s diary opens up an entirely new world of imagery—one very different from the controlled self-portraiture of her public body of work—to puzzle over. Related Content: Frida Kahlo’s Passionate Love Letters to Diego Rivera A Brief Animated Introduction to the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Discover Frida Kahlo’s Wildly-Illustrated Diary: It Chronicled the Last 10 Years of Her Life, and Then Got Locked Away for Decades is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/05/08 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |