[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, May 10th, 2019

| Time | Event |

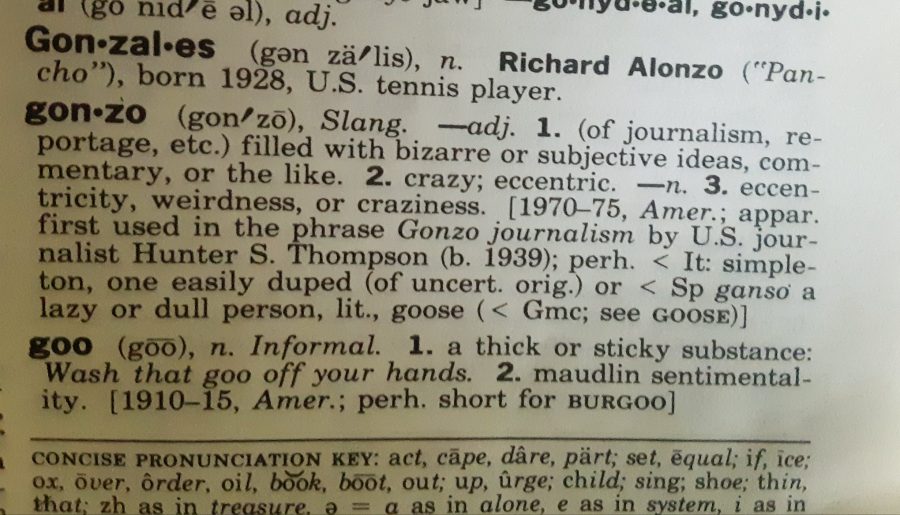

| 6:04a | “Gonzo” Defined by Hunter S. Thompson’s Personal Copy of the Random House Dictionary

via The Hunter S. Thompson Facebook Page Related Content: Hunter S. Thompson, Existentialist Life Coach, Presents Tips for Finding Meaning in Life Read 10 Free Articles by Hunter S. Thompson That Span His Gonzo Journalist Career (1965-2005) Hunter S. Thompson’s Decadent Daily Breakfast: The “Psychic Anchor” of His Frenetic Creative Life “Gonzo” Defined by Hunter S. Thompson’s Personal Copy of the Random House Dictionary is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00a | Star Trek‘s Nichelle Nichols Creates a Short Film for NASA to Recruit New Astronauts (1977) Imagine growing up in the late 1960s, witnessing at an impressionable age the heyday of the original Star Trek followed by the real-life moon landing. (If you actually did grow up in the late 1960s, just remember your childhood.) How could you not have dreamed of working on something to do with outer space, or indeed in outer space itself? It seems that both the promoters of NASA and the creators of Star Trek know that both their projects draw from the same well of wonder about the world beyond our planet. As we've previously featured here on Open Culture, William Shatner has narrated a documentary on the space shuttle as well as a Mars landing video, and Leonard Nimoy narrated a short about NASA's spacecraft Dawn. Nichelle Nichols, who played Lieutenant Uhura in the original series, also did her NASA-promoting bit — or perhaps more than her bit — by starring in the agency's 1977 recruitment film. In the years since the end of Star Trek, she had already been volunteering with NASA's push to recruit more women and minorities. "I am going to bring you so many qualified women and minority astronaut applicants for this position that if you don't choose one… everybody in the newspapers across the country will know about it," she has since remembered telling NASA at the time. In the event, NASA chose more than a few, including astronauts like Sally Ride, Guion Bluford, Judith Resnik, and Ronald McNair. "I still feel a little bit like Lieutenant Uhura on the starship Enterprise," Nichols says at the beginning of the film. "You know, now there's a 20th-century Enterprise, an actual space vehicle built by NASA and designed to put us in the business of space, and not merely space exploration." NASA's Enterprise, she explains, is "a space shuttle built to make regularly scheduled runs into space and back, just like a commercial airline," one that "may even be used to build a space station in orbit around the Earth, and this would require the services of people with a variety of skills and qualifications." At the very end, she emphasizes a different sense of variety: "I'm speaking to the whole family of humankind, minorities and women alike. If you qualify and would like to be an astronaut, now is the time. This is your NASA, a space agency embarked on a mission to improve the quality of life on planet Earth right now" — an even worthier mission, some might say, than boldly going where no man has gone before. via Boing Boing Related Content: Star Trek Celebrities William Shatner and Wil Wheaton Narrate Mars Landing Videos for NASA William Shatner Narrates Space Shuttle Documentary William Shatner Puts in a Long Distance Call to Astronaut Aboard the International Space Station Leonard Nimoy Narrates Short Film About NASA’s Dawn: A Voyage to the Origins of the Solar System Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. Star Trek‘s Nichelle Nichols Creates a Short Film for NASA to Recruit New Astronauts (1977) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts The snail may leave a trail of slime behind him, but a little slime will do a man no harm... whilst if you dance with dragons, you must expect to burn. - George R. R. Martin, The Mystery Knight As any Game of Thrones fan knows, being a knight has its downsides. It isn’t all power, glory, advantageous marriages and gifts ranging from castles to bags of gold. Sometimes you have to fight a truly formidable opponent. We’re not talking about bunnies here, though there’s plenty of documentation to suggest medieval rabbits were tough customers. As Vox Almanac’s Phil Edwards explains, above, the many snails littering the margins of 13th-century manuscripts were also fearsome foes. Boars, lions, and bears we can understand, but … snails? Why? Theories abound.

Detail from Brunetto Latini's Li Livres dou Tresor Edwards favors the one in medievalist Lilian M. C. Randall’s 1962 essay "The Snail in Gothic Marginal Warfare." Randall, who found some 70 instances of man-on-snail combat in 29 manuscripts dating from the late 1200s to early 1300s, believed that the tiny mollusks were stand ins for the Germanic Lombards who invaded Italy in the 8th century. After Charlemagne trounced the Lombards in 772, declaring himself King of Lombardy, the vanquished turned to usury and pawnbroking, earning the enmity of the rest of the populace, even those who required their services. Their profession conferred power of a sort, the kind that tends to get one labelled cowardly, greedy, malicious … and easy to put down. Which rather begs the question why the knights going toe-to- …uh, facing off against them in the margins of these illuminated manuscripts look so damn intimidated. (Conversely why was Rex Harrison’s Dr. Dolittle so unafraid of the Giant Pink Sea Snail?)

Detail from from MS. Royal 10 IV E (aka the Smithfield Decretals) Let us remember that the doodles in medieval marginalia are editorial cartoons wrapped in enigmas, much as today’s memes would seem, 800 years from now. Whatever point—or joke—the scribe was making, it’s been obscured by the mists of time. And these things have a way of evolving. The snail vs. knight motif disappeared in the 14th-century, only to resurface toward the end of the 15th, when any existing significance would very likely have been tailored to fit the times.

Detail from The Macclesfield Psalter Other theories that scholars, art historians, bloggers, and armchair medievalists have floated with regard to the symbolism of these rough and ready snails haunting the margins: The Resurrection The high clergy, shrinking from problems of the church The slowness of time The insulation of the ruling class The aristocracy’s oppression of the poor A critique of social climbers Female sexuality (isn’t everything?) Virtuous humility, as opposed to knightly pride The snail’s reign of terror in the garden (not so symbolic, perhaps…) A practical-minded Reddit commenter offers the following commentary: I like to imagine a monk drawing out his fantastical daydreams, the snail being his nemesis, leaving unsightly trails across the page and him building up in his head this great victory wherein he vanquishes them forever, never again to be plagued by the beastly buggers while creating his masterpieces. Readers, any other ideas?

Detail from The Gorleston Psalter Related Content: Killer Rabbits in Medieval Manuscripts: Why So Many Drawings in the Margins Depict Bunnies Going Bad Medieval Cats Behaving Badly: Kitties That Left Paw Prints … and Peed … on 15th Century Manuscripts Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in New York City May 13 for the next installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

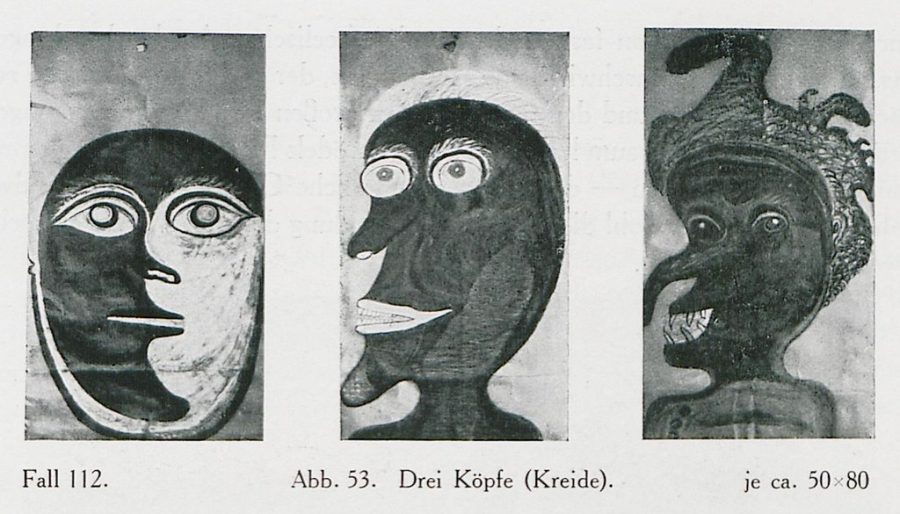

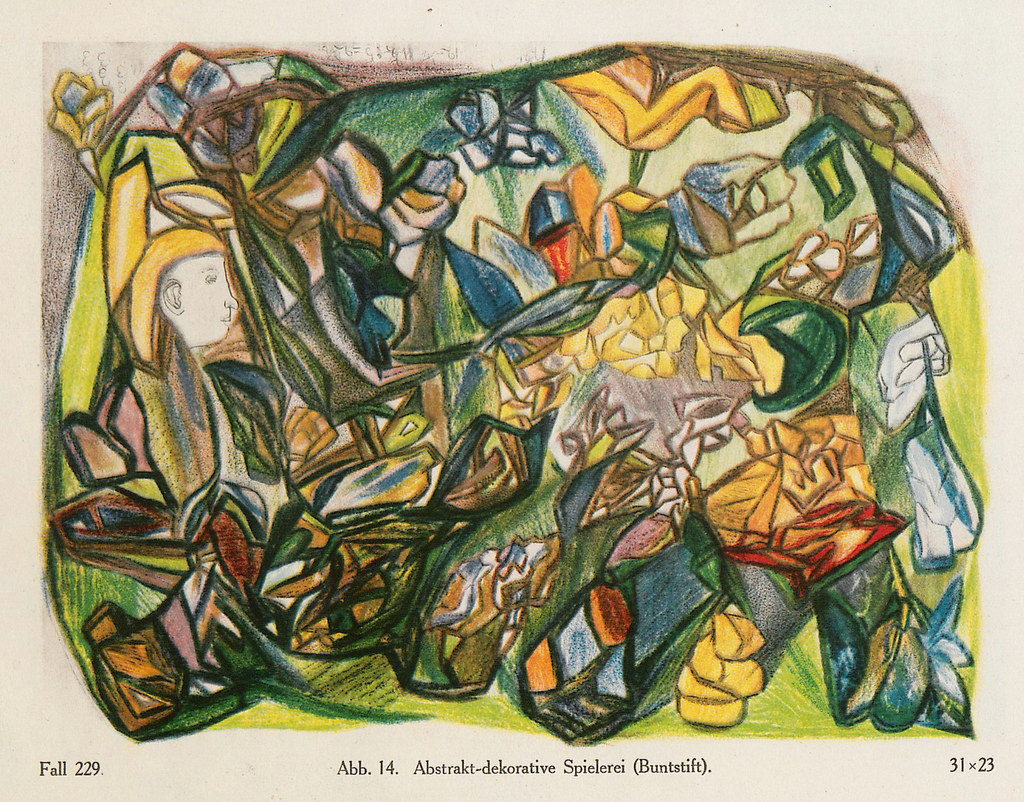

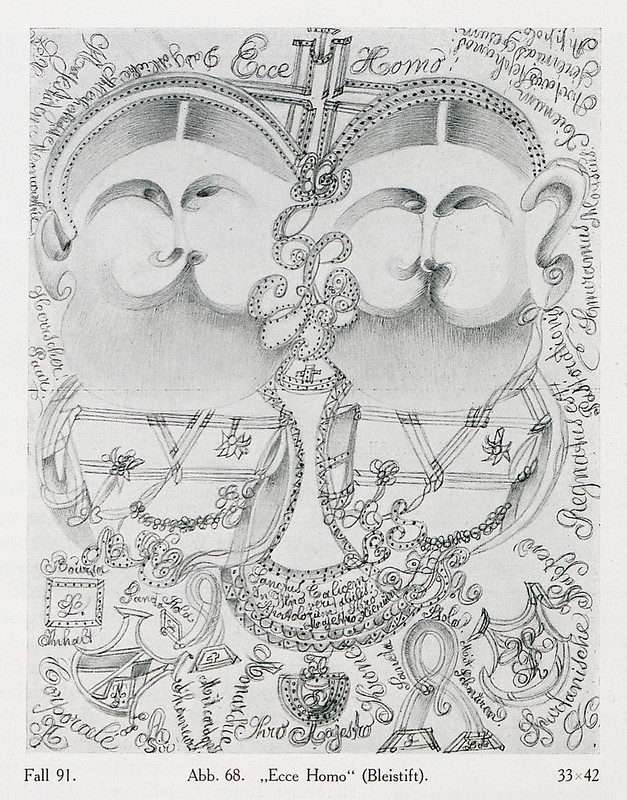

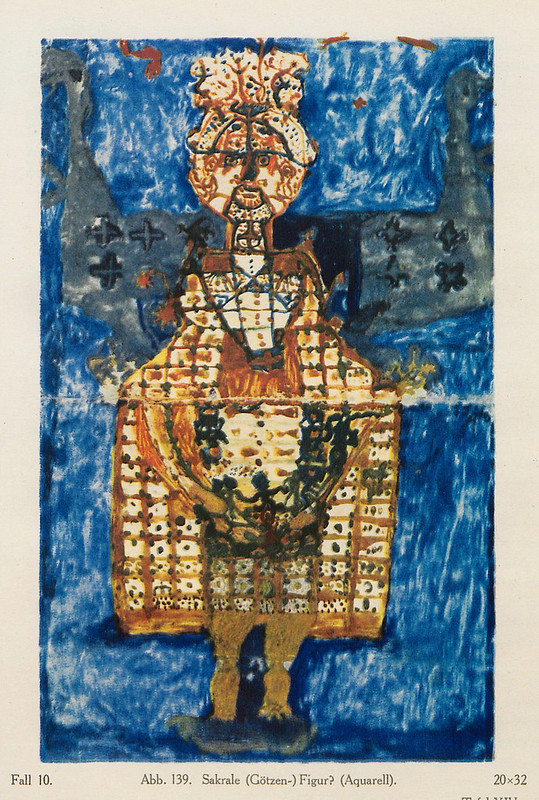

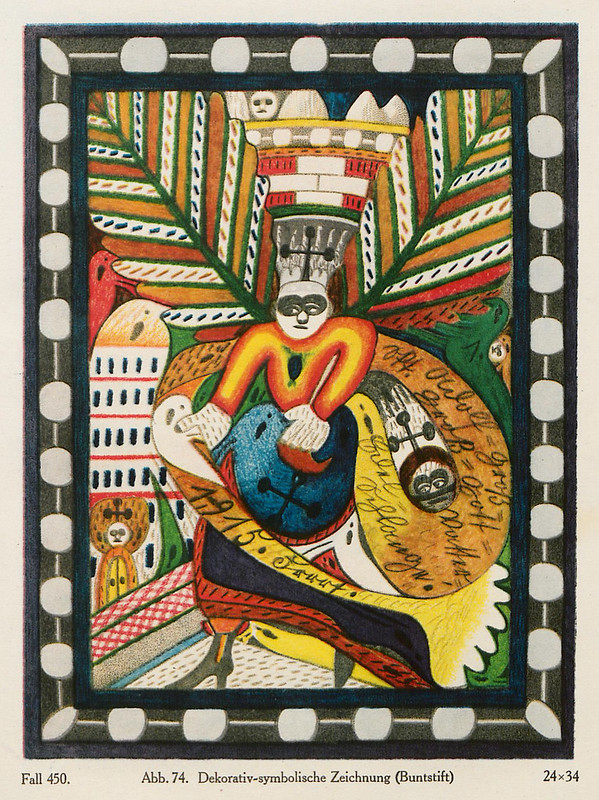

| 4:45p | The Artistry of the Mentally Ill: The 1922 Book That Published the Fascinating Work of Schizophrenic Patients, and Influenced Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky & Other Avant Garde Artists

It's an enduring irony of art history: artists whose work has come to define high culture are often characterized by various mental health issues. But the artwork of ordinary, anonymous people who struggle with those same issues is regarded as therapy, maybe, or a diversion, or a meaningless form of busy work. Though the art world has created a market for “outsider art,” it can seem like such work and its creators get viewed through an ethnographic lens rather than humanizing portraits of the artist. As Michel Foucault demonstrated in Madness and Civilization, institutions sprung over the course of modern European history to quarantine certain classes of people from the rest of society, even if it is troublingly clear to many of us that the distinctions cannot hold—hence, perhaps, the morbid fascination with the madness of famous professional artists. In 1922, German psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn challenged this reigning orthodoxy with the publication of Artistry of the Mentally Ill. The book, writes the Public Domain Review, "reflected a breakdown of high culture’s claim to ‘civilization,’ exposing the misery and turmoil at the heart of modern life.... Against the grain, the book granted voice to the previously marginalised: those incarcerated, those deemed insane, those suffering under poverty, those untrained, those in the wrong type of institution."

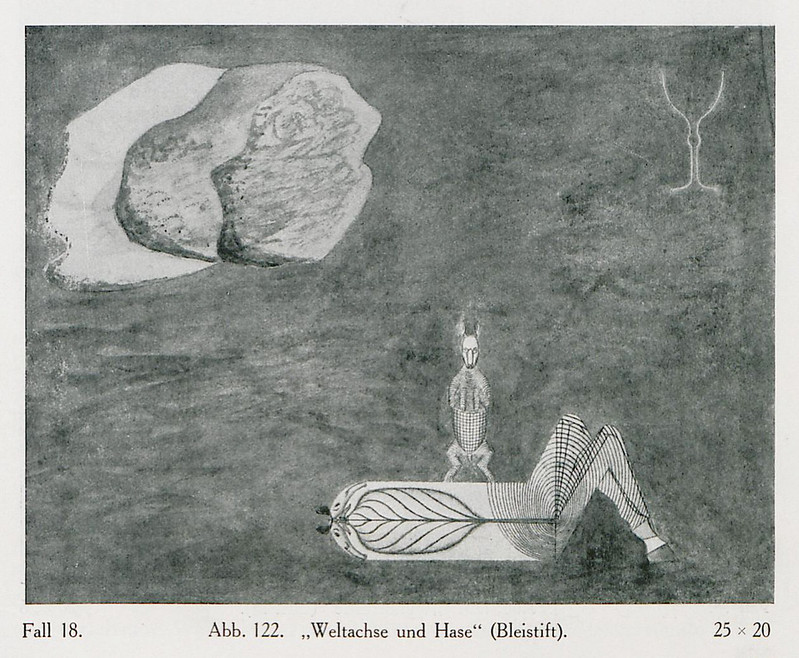

It granted those artists an audience, more to the point, of appreciative fellow artists like Paul Klee, Max Ernst, and Jean Debuffet (who would coin the term Art Brut in response). As should be abundantly clear from the small sampling of images here from the book, modernists took much from the images they saw in Prinzhorn’s book, most of it the unattributed and anonymous work of schizophrenic artists, some of whom themselves draw from earlier modernist trends.

When the Nazis held their “Degenerate Art” exhibitions in 1937, a portion of Prinzhorn’s collection of “over 5000 paintings, drawings, and carvings” was included next to the avant-garde artists it influenced. Art historian Stephanie Barron argues that “one quarter of the illustration pages in the [Degenerate Art Exhibiton’s] guide featured reproductions of the work of these psychiatric patients.” Modernists identified, in complicated ways, with those excluded from civilization, and they were subjected to the same treatment—“the insane and the avant-garde were here equated, both equally pathologized.”

Prinzhorn’s book receded into obscurity, along with the artists it carefully collected and published. It deserves to be far better known, both for its own sake and for its significant influence on the early 20th century avant-garde, and hence all subsequent avant-garde art. The book takes the work it presents seriously—not as childlike attempts or therapeutic interventions, but as expressions of six basic drives “that give rise to image making,” as the Public Domain Review summarizes. Those universal drives include “an expressive urge, the urge to play, an ornamental urge, an ordering tendency, a tendency to imitate, and the need for symbols. For Prinzhorn, image making is driven by our intense desire to leave traces.” Art, wrote Prinzhorn, represents “an urge in man not to be absorbed passively into his environment, but to impress on it traces of his existence beyond those of purposeful activity.”

The theories of artists like Kandinsky and Debuffet expressed some similar ideas. The former ascended to the realm of spirit and symbol, and the latter acerbically castigated the empty, out-of-touch veneration of high culture. Who knows what the artists here had in mind when creating their work? In Prinzhorn’s analysis, theoretical concerns may be largely irrelevant. The creation of art, by anyone, is a universal human drive that requires no special training, no social sanction, no web of brokers, curators, and collectors. Maybe this is a threatening message to people who police the boundaries of culture. The middle classes of his day, wrote Debuffet, were "convinced that [their] fashionable knowledge legitimizes the preservation of their caste. They work at persuading the lower classes of this, at convincing some of them of the necessity to safeguard art, that is to say armchairs, that is to say the bourgeois who know with which silk it is proper to upholster these armchairs." Reducing art to a status symbol turns it into so much furniture, he argued; a "recourse to antique styles takes the place of good taste." In the "raw art" of the mentally ill, Debuffet and other modernists saw a renewal of a primal human drive, the creative act.

Prinzhorn’s neglected book is out of print, though you can purchase an expensive 1972 edition on Amazon, and even an expensive Kindle version. See much more of this incredible artwork at the Public Domain Review and read brief profiles from the ten schizophrenic artists Prinzhorn identified in a later section of the book. Artists like Karl Brendel, an amputee former bricklayer from Turingian, who carved haunting wood sculptures and began his art career sculpting with chewed bread, and August Neter, to whom 10,000 figures once appeared in a single vision that later became the subject of enigmatic pencil drawings like World Axis and Rabbit, below.

Related Content: Artist Draws Nine Portraits on LSD During 1950s Research Experiment Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Artistry of the Mentally Ill: The 1922 Book That Published the Fascinating Work of Schizophrenic Patients, and Influenced Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky & Other Avant Garde Artists is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/05/10 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |