[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, May 14th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Would You Go Back to 1889 and Take Out Baby Hitler? Time-Travel Expert James Gleick Answers the Philosophical Question The vast majority of us have no inclination to kill anyone, much less a small child. But what if we had the chance to kill baby Adolf Hitler, preventing the Holocaust and indeed the Second World War? That hypothetical question has endured for a variety of reasons, touching as it does on the concepts of genocide and infant murder in forms even more highly charged than usual. It also presents, in the words of Time Travel: A History author James Gleick, "two problems at once. There's a scientific problem — you can set your mind to work imagining, 'Could such a thing be possible and how would that work?' And then there's an ethical problem. 'If I could, would I, should I?'" By the simplest analysis, writes Vox's Dylan Matthews, the question comes down to, "Is it ethical to kill one person to save 40-plus million people?" But time-travel fiction has been around long enough that we've all internalized the message that it's not quite so simple. We can even question the assumption that killing baby Hitler would prevent the Holocaust and World War II in the first place. Maybe those terrible events happen on any timeline, regardless of whether Hitler lives or dies: that would align with the Novikov self-consistency principle, which holds that "time travel could be possible, but must be consistent with the past as it has already taken place," and which has been dramatized in time-travel stories from La Jetée to The Terminator. Gleick doesn't have a straight answer in the Vox video on the killing-baby-hitler question above as to whether he himself would go back to 1889 and put baby Hitler out of action. "When you change history," he says of the moral of the countless many time travel stories he's read, "you don't get the result you're looking for. Every day, everything we do is a turning point in history, whether it's obvious to us or not." This in contrast to former Florida governor and United States presidential candidate Jeb Bush, who, when he had the big baby-Hitler question put to him by the Huffington Post, returned a hearty "Hell yea I would." But given time to reflect, even he concluded that such an act "could have a dangerous effect on everything else." It appears that some of the lessons of time-travel stories have been learned, but as for what humanity will do if it actually develops time-travel technology — maybe we'd rather not peer into the future to find out. Related Content: What Happened When Stephen Hawking Threw a Cocktail Party for Time Travelers (2009) Professor Ronald Mallett Wants to Build a Time Machine in this Century … and He’s Not Kidding Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. Would You Go Back to 1889 and Take Out Baby Hitler? Time-Travel Expert James Gleick Answers the Philosophical Question is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Watch “Critical Living,” a Stop-Motion Film Inspired by the 1960s Movement That Rejected Modern Ideas About Mental Illness

Along with Michel Foucault's critique of the medical model of mental illness, the work of Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing and other influential theorists and critics posed a serious intellectual challenge to the psychiatric establishment. Laing’s 1960 The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness theorized schizophrenia as a philosophical problem, not a biological one. Other early works like Self and Others and Knots made Laing something of a star in the 1960s and early 70s, though his star would fade once French theory began to take over the academy. Glasgow-born Laing is described as part of the so-called “anti-psychiatry movement”—a loose collection of psychiatrists and characters like L. Ron Hubbard, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Foucault, and Erving Goffman, pioneering sociologist and author of The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. For his part, Laing did not deny the existence of mental illness, nor oppose treatment. But he questioned the biological basis of psychological disorders and opposed the prevailing chemical and electroshock cures. He was seen not as an antagonist of psychiatry but as a “critical psychiatrist," continuing a tradition begun by Freud and Jung: “the alienist or ‘head shrinker’ as public intellectual,” as Duquesne University’s Daniel Burston writes. Like many other philosophically-minded intellectuals in his field, Laing not only offered compelling alternative theories of mental illness but also pioneered alternative therapies. He was inspired by Existentialism; the many hours he had spent “in padded cells with the men placed in his custody” while apprenticed in psychiatry in the British Army; and to a large extent by Foucault. (Laing edited the first English translation of Foucault’s Madness and Civilization.) Armed with theory and clinical experience, he co-founded the Philadelphia Association in 1965, an organization “centred on a communal approach to wellbeing,” writes Aeon, “where people who are experiencing acute mental distress live together in a Philadelphia Association house, with routine visits from therapists.” Based not in the Pennsylvania city, but in London, the Philadelphia Association still operates—along with several similar orgs influenced by Laing’s vision of therapeutic communities. In "Critical Living," the animated stop-motion film above, filmmaker Alex Widdowson excerpts interviews with “a current house therapist, a former house resident, and the UK author and cultural historian Mike Jay, to explore the thinking behind the organization’s methodology and contextualize its legacy.” For Laing, mental illnesses, even extreme psychoses like schizophrenia, are personal struggles that can best be worked through in interpersonal settings which eliminate distinctions between doctor and patient and abolish methods Laing called “confrontational.” Laing’s work began to be discredited in the mid-seventies, as breakthroughs in brain imaging provided neurological evidence for mainstream psychiatric theories, and as the culture changed and left his theories behind. A friend of Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, and Allen Ginsberg, and an intellectual hero to many in the counterculture, Laing began to move into stranger territory, holding workshops for “rebirthing” therapies and giving people around him reason to doubt his own grasp on reality. Burston lists a number of other reasons his experiments with “therapeutic community” largely fell into obscurity, including the significant investment of time and effort required. “We want a quick fix: something clean and cost-effective, not messy and time consuming.” But for many, Laing’s ideas of mental illness as an existential problem—one which could be just as much a breakthrough as a breakdown—continue to resonate, as do the many political and social critiques he and his contemporaries raised. “In the system of psychiatry,” says one interviewee in the video above, “there’s a huge emphasis on goals, and on an ending. In the more in-depth therapies, they’re more sensitive to the fact that the psyche can’t be rushed, it takes time.” via Aeon Related Content: Free Online Psychology & Neuroscience Courses Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Watch “Critical Living,” a Stop-Motion Film Inspired by the 1960s Movement That Rejected Modern Ideas About Mental Illness is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00p | Learn Philosophy with a Wealth of Free Courses, Podcasts and YouTube Videos

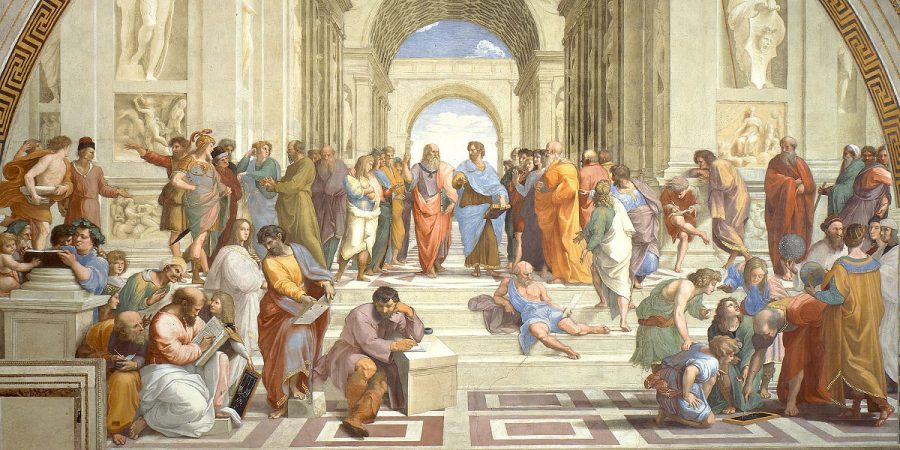

Used to be, a few thousand years ago, if you wanted to learn philosophy, you’d hang out in the agora, the public space in ancient Greece whose name turned into verbs meaning both “to shop” and “to speak in public.” Politics and metaphysics mingled freely with commerce. If a Socrates-like sage took a liking to you, you might follow him around. If not, you might pay a sophist—a word meaning wise teacher before it became a term of abuse that Plato lobbed at rivals who charged for their services. Only certain people had the means and leisure for these pursuits. Nonetheless, philosophy was a public activity, not one sequestered in libraries and seminar rooms. Even though philosophy moved indoors—to monasteries, colleges, and the libraries of aristocrats—it did not stay cooped up for long. With the modern age arrived new public squares, centered around coffeehouses where all sorts of people gathered, rubbed elbows, formed discussion groups. Philosophy may not have been the public spectacle it seemed to have been in antiquity, but neoclassical thinkers tried to recreate its character of free and open inquiry in public spaces. Widespread literacy and publishing brought philosophy to the masses in new ways. Philosophical works trickled down in affordable editions to the intellectually curious, who might read and discuss them with like-minded laypeople. But philosophy also became a professional discipline, governed by associations, conferences, journals, and arcane vocabularies. Outside of France, philosophers rarely acted as public intellectuals addressing public issues. They were academics whose primary audiences were other academics. The culture suffered immensely, one might argue, in the withdrawal of philosophy from public life. The broad outline above does not pretend to be a history of philosophy, but rather a sketch of some of the ways Western culture has engaged with philosophy, treating it as a public good and resource, or a domain of specialists and an activity divorced from ordinary life. Unfortunately for us in the 21st century, dreams of a digital agora have collapsed in the dystopian surveillance schemes of social media and the toxic sludge of comments sections. But the internet has also, in a way, returned philosophy to the public square. Philosophers can once again share knowledge freely and openly, and anyone with access can stream and download hundreds of lessons, courses, entertaining explainers, interviews, podcasts, and more. We have featured many of these resources over the years in hopes that more people will discover the art of thinking deeply and critically. Today, we gather them in a master list, below. Learn the in-depth history of philosophy from Peter Adamson’s acclaimed series The History of Philosophy… Without Any Gaps; listen in on roundtable discussions on famous thinkers and theories with the Partially Examined Life podcast, or “repave the Agora with the rubble of the Ivory Tower!” with the accessible, comprehensive philosophy videos of Carneades. These are but a few of the many quality resources you’ll find below. Technology may never recreate the early atmosphere of public philosophy—for that you’ll need to get out and mingle. But it can deliver more philosophy than anyone has ever had before, literally right into the palms of our hands. Courses 187 Free Philosophy Courses: In a neat, handy list, we've amassed a collection of free philosophy courses recorded at great universities. Pretty much every facet of philosophy gets covered here.

Wireless Philosophy: Learn about philosophy with professors from Yale, Stanford, Oxford, MIT, and more. 130+ animated videos introduce people to the practice of philosophy. The videos are free, entertaining, interesting and accessible to people with no background in the subject. School of Life: This collection of 35 animated videos offers an introduction to major Western philosophers—Wittgenstein, Foucault, Camus and more. The videos were made by Alain de Botton’s School of Life. Gregory Sadler’s Philosophy Videos: After a decade in traditional academic positions, Gregory Sadler started bringing philosophy into practice, making complex classic philosophical ideas accessible for a wide audience of professionals, students, and life-long learners. His YouTube channel includes extensive lecture series on Kierkegaard, Sartre, Hegel and more. A History of Philosophy in 81 Video Lectures: Watch 81 video lectures tracing the history of philosophy moving from Ancient Greece to modern times. Arthur Holmes presented this influential course at Wheaton College for decades and now it's online for you. Carneades: Repave the Agora with the rubble of the Ivory Tower! Put your beliefs to the test! Learn something about philosophy! Doubt something you thought you knew before. Find on this channel 400 videos on the subjects of philosophy and skepticism. What the Theory?: This collection provides short introductions to theories and theoretical approaches in cultural studies and the wider humanities. Covers semiotics, phenomenology, postmodernism, marxist literary criticism, and much more. Crash Course Philosophy: In 46 episodes, Hank Green will teach you philosophy. This course is based on an introductory Western philosophy college level curriculum. By the end of the course, you will be able to examine topics like the self, ethics, religion, language, art, death, politics, and knowledge. And also craft arguments, apply deductive and inductive reasoning, and identify fallacies. Podcasts: Partially Examined Life: Philosophy, philosophers and philosophical texts. This podcast features an informal roundtable discussion, with each episode loosely focused on a short reading that introduces at least one "big" philosophical question, concern, or idea. Recent episodes have focused on Nietzsche, Sartre and Aldous Huxley, and featured Francis Fukuyama as a guest. Hi-Phi-Nation: Created by Barry Lam (Associate Professor of Philosophy at Vassar College), Hi-Phi Nation is a philosophy podcast "that turns stories into ideas." Consider it "the first sound and story-driven show about philosophy, bringing together narrative storytelling, investigative journalism, and soundtracking." The History of Philosophy … Without Any Gaps: Created by Peter Adamson, Professor of Ancient and Medieval Philosophy at King's College London, this podcast features more than 300 episodes, each about 20 minutes long, covering the PreSocratics (Pythagoras, Zeno, Parmenides, etc) and then Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and much more. Philosophy Bites: David Edmonds (Uehiro Centre, Oxford University) and Nigel Warburton (freelance philosopher/writer) interview top philosophers on a wide range of topics. Two books based on the series have been published by Oxford University Press. There are over 400 podcasts in this collection. In Our Time: Philosophy: In Our Time is a live BBC radio discussion series exploring the history of ideas, presented by Melvyn Bragg since October 1998. It is one of BBC Radio 4's most successful discussion programmes, acknowledged to have "transformed the landscape for serious ideas at peak listening time.’" Free Courses: Related Content: Free Courses in Ancient History, Literature & Philosophy Introduction to Indian Philosophy: A Free Online Course Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Learn Philosophy with a Wealth of Free Courses, Podcasts and YouTube Videos is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/05/14 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |