[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, May 24th, 2019

| Time | Event |

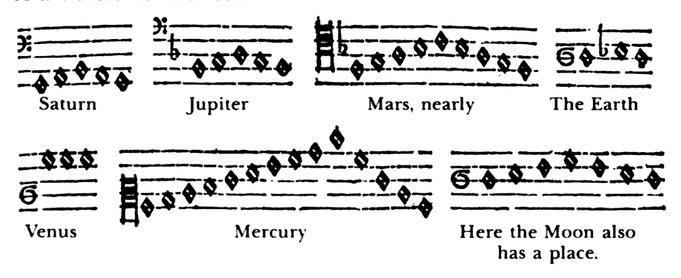

| 8:00a | Johannes Kepler Theorized That Each Planet Sings a Song, Each in a Different Voice: Mars is a Tenor; Mercury, a Soprano; and Earth, an Alto

Johannes Kepler determined just how the planets of our solar system make their way around the sun. He published his innovative work on the subject from 1609 to 1619, and in the final year of that decade he also came up with a theory that each planet sings a song, and each in a different voice at that. Mars is a tenor, Mercury is a soprano, and Earth, as the BBC show QI (or Quite Interesting) recently tweeted, "is an alto that sings two notes Mi and Fa, which Kepler read as 'Miseriam & Famem', 'misery and famine'" — two phenomena not unknown on Earth in Kepler's time, even though the scientific revolution had already started to change the way people lived. Not all of the best minds of the scientific revolution thought purely in terms of calculation. The blog ThatsMaths describes Kepler's mission as explaining the solar system "in terms of divine harmony," finding "a system of the world that was mathematically correct and harmonically pleasing." Truly divine harmony could presumably find its expression in music, an idea that led Kepler to explain "planetary motions in terms of harmonic relationships, a scheme that he called the 'song of the Earth.'" According to this scheme, "each planet emits a tone that varies in pitch as its distance from the Sun varies from perihelion to aphelion and back" — that is, from the nearest they get to the sun to the farthest they get from the sun and back — "producing a continuous glissando of intermediate tones, a 'whistling produced by friction with the heavenly light.'" Kepler named the combined result "the music of the spheres," but what does it sound like? Switzerland-based cornettist Bruce Dickey wants to give us a sense of it with Nature's Whispering Secret, "a project for a CD recording exploring the ideas about music and cosmology of Johannes Kepler." Demanding the musicianship of not just Dickey but composer Calliope Tsoupaki, singer Hana Bla?íková, and a group of singers and instrumentalists from across Europe and America as well, all "among the most distinguished musicians performing 16th-century polyphonic music today." The Indiegogo campaign for this ambitious tribute to Kepler's ideas at the intersection of science and aesthetics, which involves an album as well as a series of live performances into the year 2020, is on its very last day, so if you'd like to hear the music of the spheres for yourself, consider making a contribution. Related Content: Hear the Declassified, Eerie “Space Music” Heard During the Apollo 10 Mission (1969) NASA Puts Online a Big Collection of Space Sounds, and They’re Free to Download and Use The Soundtrack of the Universe Kepler, Galileo & Nostradamus in Color, on Google Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. Johannes Kepler Theorized That Each Planet Sings a Song, Each in a Different Voice: Mars is a Tenor; Mercury, a Soprano; and Earth, an Alto is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | How Computers Ruined Rock Music There are purists out there who think computers ruined electronic music, made it cold and alien, removed the human element: the warm, warbling sounds of analog oscillators, the unpredictability of analog drum machines, synthesizers that go out of tune and have minds of their own. Musicians played those instruments, plugged and patched them together, tried their best to control them. They did not program them. Then came digital samplers, MIDI, DAWs (digital audio workstations), pitch correction, time correction… every note, every arpeggio, every drum fill could be mapped in advance, executed perfectly, endlessly editable forever, and entirely played by machines. All of this may have been true for a short period of time, when producers became so enamored of digital technology that it became a substitute for the old ways. But analog has come back in force, with both technologies now existing harmoniously in most electronic music, often within the same piece of gear. Digital electronic music has virtues all its own, and the dizzying range of effects achievable with virtual components, when used judiciously, can lead to sublime results. But when it comes to another argument about the impact of computers on music made by humans, this conclusion isn’t so easy to draw. Rock and roll has always been powered by human error—indeed would never have existed without it. How can it be improved by digital tools designed to correct errors? The ubiquitous sound of distortion, for example, first came from amplifiers and mixing boards pushed beyond their fragile limits. The best songs seem to all have mistakes built into their appeal. The opening bass notes of The Breeder’s “Cannonball,” mistakenly played in the wrong key, for example... a zealous contemporary producer would not be able to resist running them through pitch correction software. John Bonham’s thundering drums, a force of nature caught on tape, feel “impatient, sterile and uninspired” when sliced up and snapped to a grid in Pro Tools, as producer and YouTuber Rick Beato has done (above) to prove his theory that computers ruined rock music. You could just write this off as an old man ranting about new sounds, but hear him out. Few people on the internet know more about recorded music or have more passion for sharing that knowledge. In the video at the top, Beato makes his case for organic rock and roll: “human beings playing music that is not metronomic, or ‘quantized’”—the term for when computers splice and stretch acoustic sounds so that they align mathematically. Quantizing, Beato says, “is when you determine which rhythmic fluctuations in a particular instrument’s performance are imprecise or expressive, you cut them, and you snap them to the nearest grid point.” Overuse of the technology, which has become the norm, removes the “groove” or “feel” of the playing, the very imperfections that make it interesting and moving. Beato’s thorough demonstration of how digital tools turn recorded music into modular furniture show us how the production process has become an mental exercise, a design challenge, rather than the palpable, spontaneous output of living, breathing human bodies. The “present state of affairs,” as Nick Messitte puts it, is “keyboards triggering samples quantized to within an inch of their humanity by producers in the pre-production stages.” Anyone resisting this status quo becomes an acoustic musician by default, argues Messitte, standing on one side of the “acoustic versus synthetic” divide. Whether the two modes of music can be harmoniously reconciled is up for debate, but at present, I’m inclined to agree with Beato: digital recording, processing, and editing technologies, for all their incredible convenience and unlimited capability, too easily turn rhythms made with the elastic timing of human hearts and hands into machinery. The effect is fatiguing and dull, and on the whole, rock records that lean on these techniques can't stand up to those made in previous decades or by the few holdouts who refuse to join the arms race for synthetic pop perfection. Related Content: Brian Eno Explains the Loss of Humanity in Modern Music Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Computers Ruined Rock Music is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/05/24 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |