[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, June 11th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Watch The Meaning of Life: One of the Best Animated Short Films Ever Made Traces the Evolution of Life, the Universe & Beyond They say creativity is born of limitations. If that's true, then is any animator working today more creative than Don Hertzfeldt? "The stars of his movies are all near-featureless stickmen with dots for eyes and a single line for a mouth," writes The Guardian's David Jenkins in an appreciation of Hertzfeldt, whose "method of making grand existential statements with almost recklessly modest means" — animating everything himself, and doing it all with traditional hand-drawing-and-film-camera methods that at no point involve computer-generated imagery — "has made his cinematic oeuvre one of the most fascinating and enjoyable of all contemporary American directors." As an example Jenkins holds up 2005's The Meaning of Life, which "tackled nothing less than the nature of organic life in the known universe, addressing the painstaking development of the human form through a series of (often highly amusing) Darwinian transmutations." You can glimpse its four-year-long animation process, which appears to have been almost as painstaking, in time-lapse making-of documentary Watching Grass Grow. At Short of the Week, Rob Munday writes that, though The Meaning of Life takes on "a subject already familiar to the format (evolution has also been portrayed in short film by animators Michael Mills, Claude Cloutier and I’m sure many more)," it also sees Hertzfeldt adding "his own distinct take to proceedings with his unmistakable style and injections of dark humor." That special brand of humor has long been familiar to the many viewers who have stumbled across Hertzfeldt's earlier Rejected, a short composed of even shorter shorts originally commissioned — and, yes, rejected — by the Family Learning Channel. As one of the first animations to "go viral" in the Youtube era, Rejected not only made Hertzfeldt's name but paved the way for projects at once more ambitious, more surreal, more comic, and more serious: take the 65-minute It's Such a Beautiful Day, which follows one of his signature stickmen into prolonged neurological decline. The Meaning of Life might seem positive by comparison, but its cosmic sweep belies Hertzfeldt's underlying critique of all that evolution has produced. As Jenkins paraphrases it, "Were we really worth all that effort?" The Meaning of Life--which Time Out New York named the film one of the "thirty best animated short films ever made"--has been added to our list of Free Animations, a subset of our collection, 1,150 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc. Related Content: Free Animated Films: From Classic to Modern Carl Sagan Explains Evolution in an Eight-Minute Animation Alan Watts Dispenses Wit & Wisdom on the Meaning of Life in Three Animated Videos Why Man Creates: Saul Bass’ Oscar-Winning Animated Look at Creativity (1968) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. Watch The Meaning of Life: One of the Best Animated Short Films Ever Made Traces the Evolution of Life, the Universe & Beyond is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

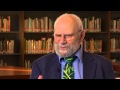

| 11:00a | Oliver Sacks Promotes the Healing Power of Gardens: They’re “More Powerful Than Any Medication” Early European explorers left the continent with visions of gardens in their heads: The Garden of Eden, the Garden of the Hesperides, and other mythic realms of abundance, ease, and endless repose. Those same explorers left sickness, war, and death only to find sickness, war, and death—much of it exported by themselves. The garden became de-mythologized. Natural philosophy and modern methods of agriculture brought gardens further down to earth in the cultural imagination. Yet the garden remained a special figure in philosophy, art, and literature, a potent symbol of an ordered life and ordered mind. Voltaire’s Candide, the riotous satire filled with gardens both fantastical and practical, famously ends with the dictate, “we must cultivate our garden.” The tendency to read this line as strictly metaphorical does a disservice to the intellectual culture created by Voltaire and other writers of the period—Alexander Pope most prominent among them—for whom gardening was a theory born of practice. [Error: Irreparable invalid markup ('<div [...] http://cdn8.openculture.com/>') in entry. Owner must fix manually. Raw contents below.] <div class="oc-video-wrapper">

<div class="oc-video-container">

<p><a href="http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/OpenCulture/~3/Xmb5oZaomQE/http//www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z9EMPkia4xQ"><img src="http://img.youtube.com/vi/Z9EMPkia4xQ/default.jpg" border="0" width="320" /></a></p>

</div>

<p> <!-- /oc-video-embed -->

</p></div>

<p><!-- /oc-video-wrapper --></p>

<p>Early European explorers left the continent with visions of gardens in their heads: The Garden of Eden, the <a href="https://www.greekmythology.com/Other_Gods/Minor_Gods/Hesperides/hesperides.html">Garden of the Hesperides</a>, and other mythic realms of abundance, ease, and endless repose. Those same explorers left sickness, war, and death only to find sickness, war, and death—much of it exported by themselves. The garden became de-mythologized. Natural philosophy and modern methods of agriculture brought gardens further down to earth in the cultural imagination.</p>

<p>Yet the garden remained a special figure in philosophy, art, and literature, a potent symbol of an ordered life and ordered mind. Voltaire’s <a href="https://amzn.to/2WCgCE2"><em>Candide</em></a>, the riotous satire filled with gardens both fantastical and practical, famously ends with the dictate, “we must cultivate our garden.” The tendency to read this line as strictly metaphorical does a disservice to the intellectual culture created by Voltaire and other writers of the period—<a href="https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/alexander-pope">Alexander Pope</a> most prominent among them—for whom gardening was a theory born of practice.</p>

<div class="oc-center-da" http://cdn8.openculture.com/="http://cdn8.openculture.com/">

<p>Exiled from France in 1765, Voltaire retreated to a villa in Geneva called Les Délices, “The Delights.” There, writes Adam Gopnik at <em><a href="https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/03/07/voltaires-garden">The New Yorker</a></em>, he “quickly turned his exile into a desirable condition…. When he wrote that it was our duty to cultivate our garden, he really knew what it meant to cultivate a garden.” Enlightenment poets and philosophers did not dwell on the scientific reasons why gardens might have such salutary effects on the psyche. And neither does neurologist Oliver Sacks, who also wrote of gardens as health-bestowing havens from the chaos and noise of the world, and more specifically, from the city and brutal commercial demands it represents.</p>

<p>For Sacks that city was not Paris or London but, principally, New York, where he lived, practiced, and wrote for fifty years. Nonetheless, in his essay “<a href="https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/18/opinion/sunday/oliver-sacks-gardens.html">The Healing Power of Gardens</a>,” he invokes the European history of gardens, from the medieval <em>hortus </em>to grand Enlightenment botanical gardens like <a href="https://www.kew.org/">Kew</a>, filled with exotic plants from “the Americas and the Orient.” Sacks writes of his student days, where he “discovered with delight a very different garden—the <a href="https://www.obga.ox.ac.uk/">Oxford Botanic Garden</a>, one of the first walled gardens established in Europe,” founded in 1621.</p>

<p>“It pleased me to think,” he recalls, referring to key Enlightenment scientists, “that Boyle, Hooke, Willis and other Oxford figures might have walked and meditated there in the 17th century.” In that time, cultivated gardens were often the private preserves of landed gentry. Now, places like the <a href="https://www.nybg.org/">New York Botanical Garden</a>, whose virtues Sacks extolls in the video above, are open to everyone. And it is a good thing, too. Because gardens can serve an essential public health function, whether we’re stressed and generally fatigued or suffering from a mental disorder or neurological condition:</p>

<blockquote><p><em>I cannot say exactly how nature exerts its calming and organizing effects on our brains, but I have seen in my patients the restorative and healing powers of nature and gardens, even for those who are deeply disabled neurologically. In many cases, gardens and nature are more powerful than any medication.</em></p></blockquote>

<p>“In forty years of medical practice,” the physician writes, “I have found only two types of non-pharmaceutical ‘therapy’ to be vitally important for patients with chronic neurological diseases: music and gardens.” A garden also represents—for Sacks and for artists like Virginia Woolf—“a triumph of resistance against the merciless race of modern life,” as <a href="https://www.brainpickings.org/2019/05/27/oliver-sacks-gardens/">Maria Popova writes at Brain Pickings</a>, a pace “so compulsively focused on productivity at the cost of creativity, of lucidity, of sanity.”</p>

<p>Voltaire’s prescription to tend our gardens has made <em><a href="https://amzn.to/2WCgCE2">Candide</a> </em>into a watchword for caring for and appreciating our surroundings. (It’s also now the name of a <a href="https://candidegardening.com/about">gardening app</a>). Sacks’ recommendations should inspire us equally, whether we’re in search of creative inspiration or mental respite. “As a writer,” he says, “I find gardens essential to the creative process; as a physician, I take my patients to gardens whenever possible. The effect, he writes, is to be “refreshed in body and spirit,” absorbed in the “deep time” of nature, as he <a href="https://www.brainpickings.org/2018/07/17/oliver-sacks-beauty-deep-time/">writes elsewhere</a>, and finding in it “a profound sense of being at home, a sort of companionship with the earth,” and a remedy for the alienation of both mental illness and the grinding pace of our usual form of life.</p>

<p>via <a href="https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/18/opinion/sunday/oliver-sacks-gardens.html">New York Times</a>/<a href="https://www.brainpickings.org/2019/05/27/oliver-sacks-gardens/">Brain Pickings</a></p>

<p><strong>Related Content:</strong></p>

<p><a href="http://www.openculture.com/2019/05/oliver-sacks-recommends-46-books.html">Oliver Sacks’ Recommended Reading List of 46 Books: From Plants and Neuroscience, to Poetry and the Prose of Nabokov</a></p>

<p><a href="http://www.openculture.com/2018/09/the-animated-mind-of-oliver-sacks.html">A First Look at The Animated Mind of Oliver Sacks, a Feature-Length Journey Into the Mind of the Famed Neurologist</a></p>

<p><a href="http://www.openculture.com/2017/12/how-the-japanese-practice-of-forest-bathing-can-lower-stress-levels-and-fight-disease.html">How the Japanese Practice of “Forest Bathing”—Or Just Hanging Out in the Woods—Can Lower Stress Levels and Fight Disease</a></p>

<p><em><a href="http://about.me/jonesjoshua">Josh Jones</a> is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at <a href="https://twitter.com/jdmagness">@jdmagness</a></em></p>

<!-- permalink:http://www.openculture.com/2019/06/oliver-sacks-promotes-the-healing-properties-of-gardens.html--><p><a rel="nofollow" href="http://www.openculture.com/2019/06/oliver-sacks-promotes-the-healing-properties-of-gardens.html">Oliver Sacks Promotes the Healing Power of Gardens: They’re “More Powerful Than Any Medication”</a> is a post from: <a href="http://www.openculture.com">Open Culture</a>. Follow us on <a href="https://www.facebook.com/openculture">Facebook</a>, <a href="https://twitter.com/#!/openculture">Twitter</a>, and <a href="https://plus.google.com/108579751001953501160/posts">Google Plus</a>, or get our <a href="http://www.openculture.com/dailyemail">Daily Email</a>. And don't miss our big collections of <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freeonlinecourses">Free Online Courses</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freemoviesonline">Free Online Movies</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/free_ebooks">Free eBooks</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freeaudiobooks">Free Audio Books</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freelanguagelessons">Free Foreign Language Lessons</a>, and <a href="http://www.openculture.com/free_certificate_courses">MOOCs</a>.</p>

<div class="feedflare">

<a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=Xmb5oZaomQE:RM5B4spFCYs:yIl2AUoC8zA"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?d=yIl2AUoC8zA" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=Xmb5oZaomQE:RM5B4spFCYs:V_sGLiPBpWU"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?i=Xmb5oZaomQE:RM5B4spFCYs:V_sGLiPBpWU" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=Xmb5oZaomQE:RM5B4spFCYs:gIN9vFwOqvQ"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?i=Xmb5oZaomQE:RM5B4spFCYs:gIN9vFwOqvQ" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=Xmb5oZaomQE:RM5B4spFCYs:qj6IDK7rITs"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?d=qj6IDK7rITs" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=Xmb5oZaomQE:RM5B4spFCYs:I9og5sOYxJI"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?d=I9og5sOYxJI" border="0"></img></a>

</div><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~r/OpenCulture/~4/Xmb5oZaomQE" height="1" width="1" alt="" /> |

| 3:43p | Meet Gerda Taro, the First Female Photojournalist to Die on the Front Lines

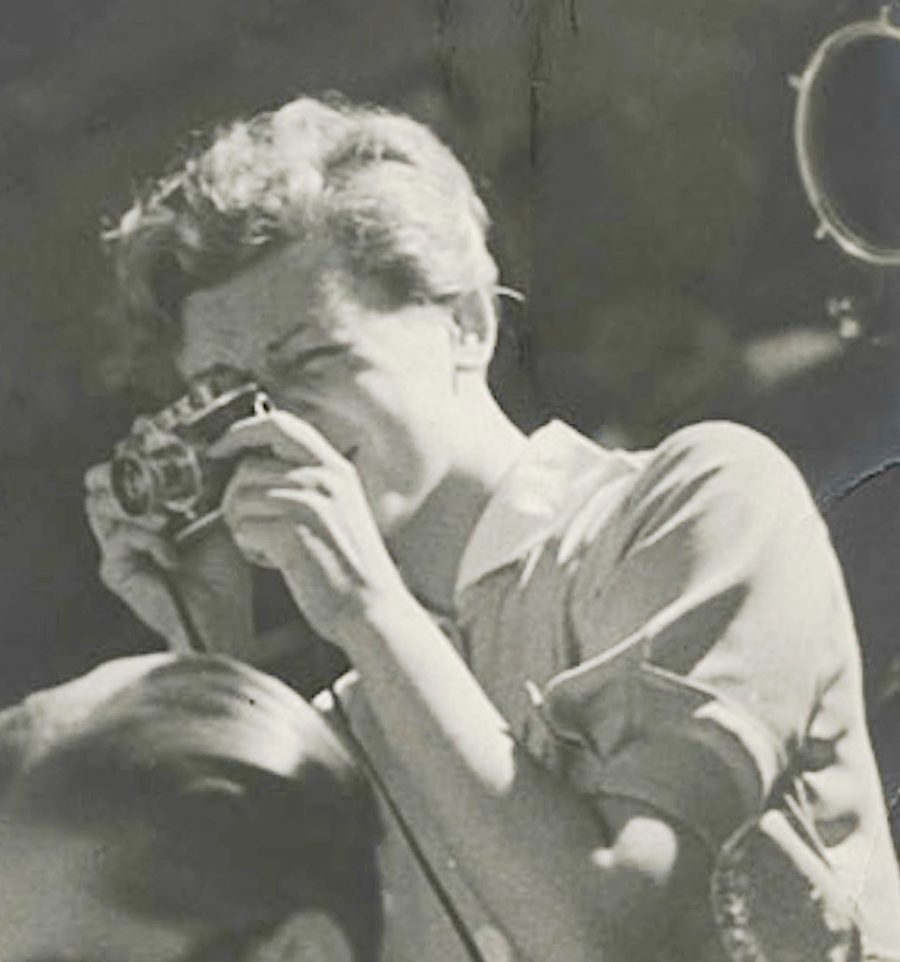

Gerda Taro by Anonymous, via Wikimedia Commons We may know a few names of historic women photographers, like Julia Margaret Cameron, Dorothea Lange, or Diane Arbus, but the significant presence of women in photography from its very beginnings doesn’t get much attention in the usual narrative, despite the fact that “by 1900,” as photographer Dawn Oosterhoff writes, census records in Britain and the U.S. showed that “there were more than 7000 professional women photographers,” a number that only grew as decades passed. As photographic equipment became smaller, lighter, and more portable, photographers moved out into more challenging and dangerous situations. Among them were women who “fought tradition and were among the pioneer photojournalists,” working alongside men on the front lines of war zones around the world. War photographers like Lee Miller—former Vogue model, Man Ray muse, and Surrealist artist—showed a side of war most people didn’t see, one in which women warriors, medical personnel, support staff, and workers, played significant roles and bore witness to mass suffering and acts of heroism. Image via Flickr Creative Commons

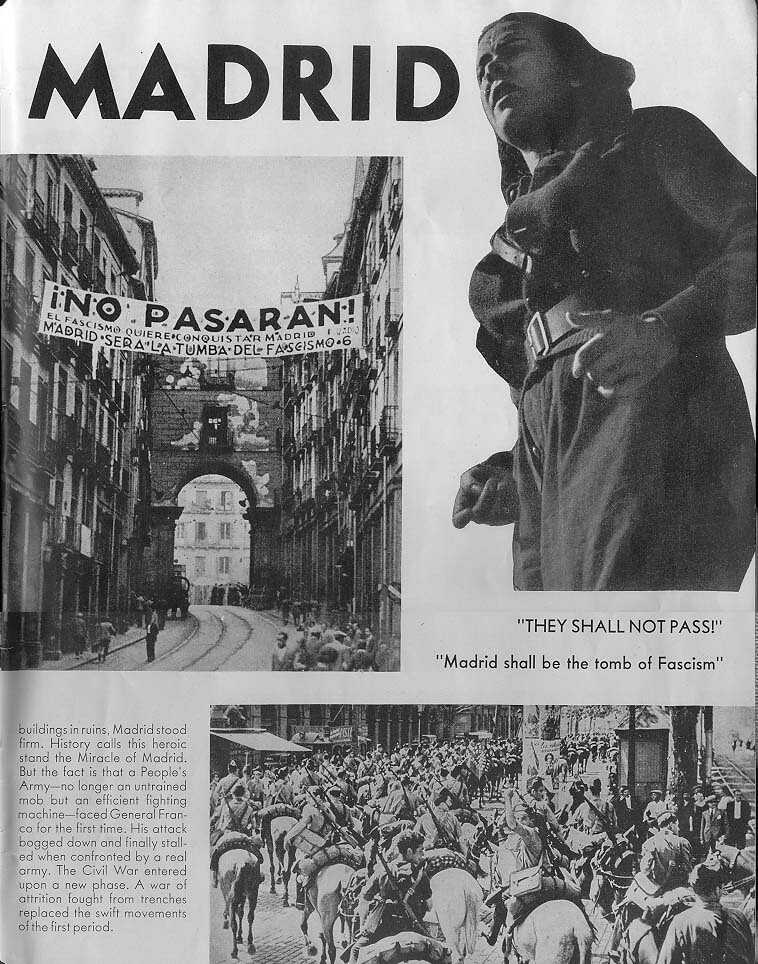

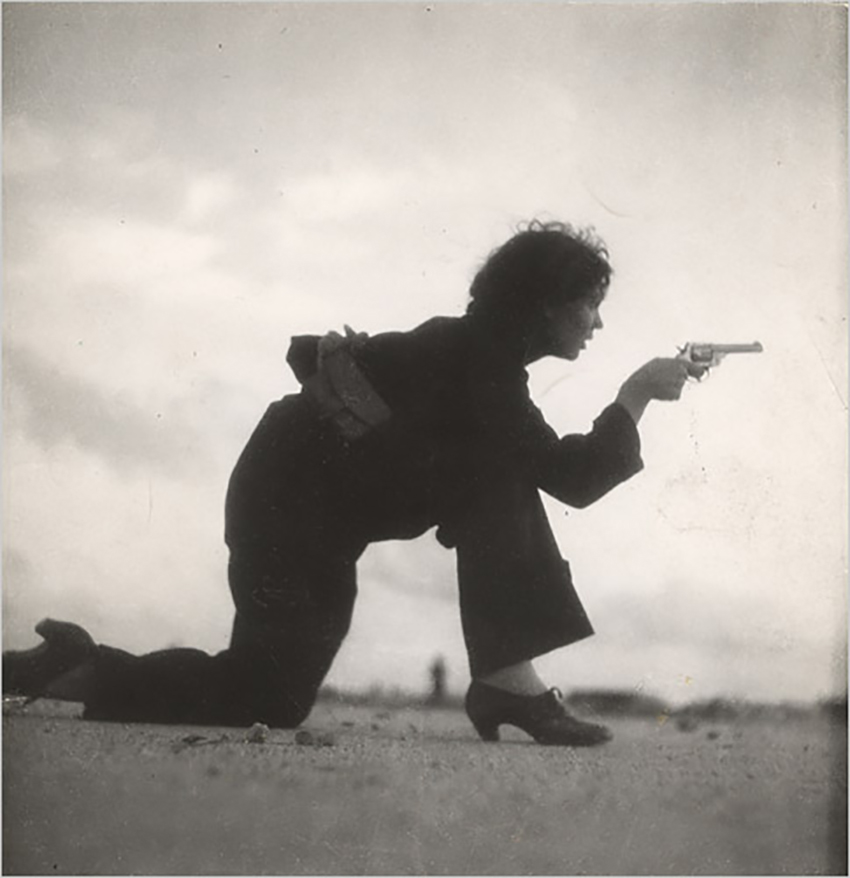

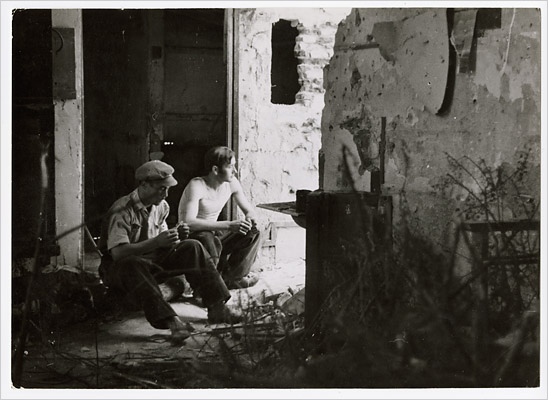

Before Miller captured the devastation at the European front, the horrors of Dachau, and Hitler’s bathtub, another female war photographer, Gerda Taro, documented the front lines of the Spanish Civil War. “One of the world’s first and greatest war photographers,” writes Giles Trent at The Guardian, Taro “died while photographing a chaotic retreat after the Battle of Brunete, shortly after Franco’s troops had one a major victory,” just days away from her 27th birthday. She was the first female photojournalist to be killed in action on the frontline and a major star in France at the time of her death. Woman Training for a Republican Militia, by Gerda Taro, via Wikimedia Commons “On 1 August 1937,” notes a Magnum Photos bio, “thousands of people lined the streets of Paris to mourn the death” of Taro. The “26-year-old Jewish émigré from Leipzig… was eulogized as a courageous reporter who had sacrificed her life to bear witness to the suffering of civilians and troops…. The media proclaimed her a left-wing heroine, a martyr of the anti-fascist cause and a role model for young women everywhere.” Taro had fled to France in in 1933, after being arrested by the Nazis for distributing anti-fascist leaflets in Germany. She was determined to continue the fight in her new country.

Republican Soldiers at the Navacerrada Pass, by Gerda Taro, via Wikimedia Commons Taro met another Jewish émigré, well-known Hungarian photographer Robert Capa, just getting his start at the time. The two became partners and lovers, arriving in Barcelona in 1936, “two-and-a-half weeks after the outbreak of the war.” Like Miller, Taro was drawn to women on the battlefield. In one of her first assignments, she documented militiawomen of the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia training on a beach. “Motivated by a desire to raise awareness of the plight of Spanish civilians and the soldiers fighting for liberty,” her clear sympathies give her work depth and immediacy.

Republican Dinamiteros, in the Carabanchel Neighborhood of Madrid, by Gerda Taro, via Wikimedia Commons Taro’s photographs “were widely reproduced in the French leftist press,” points out the International Center of Photography. She “incorporated the dynamic camera angles of New Vision photography as well as a physical and emotional closeness to her subject.” After she was crushed by a tank in 1937, many of her photographs were incorrectly credited to Capa, and she sank into obscurity. She has achieved renewed recognition in recent years, especially after a trove of 4,500 negatives containing work by her and Capa was discovered in Mexico City. Although she had been warned away from the front, Taro “got into this conviction that she had to bear witness,” says biographer Jane Rogoyska, “The troops loved her and she kept pushing.” She paid with her life, died a hero, and was forgotten until recently. Her legacy is celebrated in Rogoyska’s book, a novel about her and Capa by Susana Fortes, an International Center of Photography exhibition, film projects in the works, and a Google Doodle last August on her birthday. Learn more about Taro’s life and see many more of her captivating images, at Magnum Photos. Related Content: Visit a New Digital Archive of 2.2 Million Images from the First Hundred Years of Photography 1,600 Rare Color Photographs Depict Life in the U.S During the Great Depression & World War II Annie Leibovitz Teaches Photography in Her First Online Course Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Meet Gerda Taro, the First Female Photojournalist to Die on the Front Lines is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/06/11 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |